Types of megalithic monuments in northeastern Germany

The various types of megalithic monuments in northeastern Germany were last compiled by Ewald Schuldt in the course of a project to excavate megalithic tombs from the Neolithic Era, which was conducted between 1964 and 1972 in the area of the northern districts of East Germany. His aim was to provide a "classification and naming of the objects present in this field of research".[1] In doing so it utilised a classification by Ernst Sprockhoff, which in turn was based on an older Danish model.[2]

Naming scheme

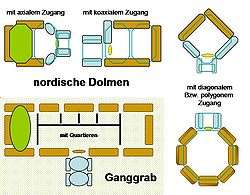

Schuldt listed six types:

- the simple dolmen (Urdolmen)

- the extended dolmen (erweiterte Dolmen)

- the great dolmen (Großdolmen)

- the passage grave (Ganggrab)

- the long barrow without a chamber (Hünenbett ohne Kammer)

- the stone cist (Steinkiste)

Geographic distribution

As part of a joint venture between the Institute of Prehistory and Early History of the East German Academy of Sciences in Berlin and the Museum of Prehistory and Early History at Schwerin a total of 106 of 1145 detectable megalithic were excavated from 1965 to 1970 and the graves that were found were documented and classified. The figures show the numbers of various types for the three former East German districts Rostock, Schwerin and Neubrandenburg, roughly corresponding to the territory of current Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[3]

Based on the different distributions of the types of megalithic tomb, Schuldt later divided northeastern Germany into six neolithic landscape types:[4]

| A | Long barrows without chambers | In the southwest of the former Bezirk of Schwerin |

| B | Passage graves | In the northwest of the former Bezirke of Rostock and Schwerin |

| C | Extended or rectangular dolmens | In the lake district of the former Bezirke of Schwerin and Neubrandenburg |

| D | Great dolmens with ante-chambers | In the northeast of the former Bezirk of Neubrandenburg |

| E | Great dolmens with draught excluders (Windfang) | On the island of Rügen |

| F | Stone cists | In the southeast of the former Bezirk of Neubrandenburg |

Only the polygonal dolmens had no clear centre of gravity in terms of their distribution. They were very much a Danish-Schleswig-Swedish phenomenon.

Due to their technical designs, Schuldt concluded that the monuments were built under "the supervision of a specialist or group of specialists", the so-called "construction unit theory" (Bautrupptheorie).[5]

Cultures

Ewald Schuldt deduced that the excavated megalithic sites were constructed by followers of the Funnelbeaker culture.[6] The oldest grave artefacts were discovered in a simple dolmen near Barendorf (county of Grevesmühlen); one collared flask (Kragenflasche) was dated to the end of the Early Neolithic, from which Ewald Schuldt assessed that the archaeological find was a primary burial (Erstbestattung).

In 43 graves there were secondary burials by the Globular Amphora culture, most of which were dated to the more recent Middle Neolithic. Because in several gravesites these discoveries and those of the Funnelbeaker culture were not clearly separated from one another, Schuldt did not specifically refer to them as secondary burials. The Globular Amphora culture is found in one simple dolmen, in 2 large chambers, in 10 extended dolmens, 12 passage graves and 17 great dolmens.

Secondary burials of the Single Grave culture, which followed in the Late Neolithic, are found in 2 simple dolmens, 5 extended dolmens, 12 great dolmens and 7 passage graves. In addition there were 9 complexes assessed as belonging to the Havelland culture (also called the Elb-Havel Group).

Ewald Schuldt realised that the Funnelbeaker and Globular Amphora cultures buried their dead in the main chamber hall (Kammerdiele) or a secondary hall and then filled the graves in. He thus concluded that there were close links between the builders of the megalithic sites, the Funnelbeaker culture and members of the Globular Amphora culture. By contrast, the burials of the Single Grave culture always took place in the upper part of the earth fill (Füllboden) of the grave chamber and access to the site was generally achieved by force from above. This suggested that they were carried out by strangers who no longer had any connexion with the burial concept of the builders of the megalithic sites.[7]

Material

In developing an architecture that was suited in terms of building material and shape to the significance of the cult sites, the builders of these megalithic tombs only had available to them the raw materials of glacial deposits.[8] These materials, particularly the large stones and boulders of the glacial erratics, were selected and worked in order to build the sites. It was difficult therefore to overcome the variability of the raw materials in terms of quality and quantity.

Sources

- ↑ Schuldt 1972, p. 13

- ↑ Ernst Sprockhoff: Die nordische Megalithkultur, 1938, cited in Schuldt 1972, p. 10

- ↑ Schuldt 1972, p. 14

- ↑ Schuldt 1972, p. 106

- ↑ Schuldt 1972, p. 106

- ↑ Schuldt 1972, p. 71.

- ↑ Schuldt 1972, p. 89

- ↑ Otto Gehl in Ewald Schuldt, 1972, p. 114

External links

Literature

- Ewald Schuldt: Die mecklenburgischen Megalithgräber. Untersuchungen zu ihrer Architektur und Funktion. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin, 1972 (Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Bezirke Rostock, Schwerin und Neubrandenburg. 6, ISSN 0138-4279).

- Märta Strömberg: Die Megalithgräber von Hagestad. Zur Problematik von Grabbauten und Grabriten. Habelt, Bonn 1971, ISBN 3-7749-0195-3 (Acta Archaeologica Lundensia. Series in 8°. No. 9).