Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt

| Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Kushite Egypt in 700 BC. | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Napata | |||||||||||||

| Languages | Ancient Egyptian, Nubian | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | |||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||

| • | 760 BC-752 BC | Kashta (first) | ||||||||||||

| • | 664 BC-656 BC | Tantamani (last) | ||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||

| • | Established | 760 BC | ||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 656 BC | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, known as the Nubian Dynasty or the Kushite Empire, was the last dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt.

The 25th dynasty was a line of rulers originating in the Nubian Kingdom of Kush – in present-day northern Sudan and southern Egypt – and most saw Napata as their spiritual homeland. They reigned in part or all of Ancient Egypt from 760 BC to 656 BC.[1] The dynasty began with Kashta's invasion of Upper Egypt and culminated in several years of both successful and unsuccessful war with the Mesopotamian based Assyrian Empire. The 25th Dynasty's reunification of Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt, and also Kush (Nubia) created the largest Egyptian empire since the New Kingdom. They assimilated into society by reaffirming Ancient Egyptian religious traditions, temples, and artistic forms, while introducing some unique aspects of Kushite culture.[2] It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.[3][4][5] After the Assyrian kings Sargon II and Sennacherib defeated attempts by the Nubian kings to gain a foothold in the Near East, their successors Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt and defeated and drove out the Nubians. War with Assyria resulted in the end of Kushite power in Northern Egypt and the conquest of Egypt by Assyria. They were succeeded by the Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt, initially a puppet dynasty installed by and vassals of the Assyrians, the last native dynasty to rule Egypt before the Persian conquest.

Rulers

The known rulers, in the History of Egypt, for the twenty-fifth dynasty are the following:

| Pharaoh | Throne Name | Reign (BC) | Pyramid | Consort(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kashta | Maatre | c. 760 BC – c. 752 BC | Kurru 8 | Queen Pebatjma (Kurru 7?) |

| Piye | Menkheperre Usermaatre | c. 752 BC – 721 BC | Kurru 17 | Queen Tabiry (Kurru 53) Queen Abar (Nuri 53?) Queen Khensa (Kurru 4) Queen Peksater (Kurru 54) Nefrukekashta (Kurru 52) |

| Shabaka | Neferkare | 721 BC – 707 BC | Kurru 15 | Queen Qalhata (Kurru 5) Queen Mesbat Queen Tabekenamun? |

| Shebitku | Djedkare | 707 BC – 690 BC | Kurru 18 | Queen Arty (Kurru 6) |

| Taharqa | Khunefertumre | 690 – 664 BC | Nuri 1 | Queen Takahatenamun (Nuri 21?) Queen Atakhebasken (Nuri 36) Queen Naparaye (Kurru 3) Queen Tabekenamun? |

| Tantamani | Bakare | 664 – 656 BC (died 653 BC) | Kurru 16 | Queen Piankharty Queen [..]salka Queen Malaqaye? (Nuri 59) |

The period starting with Kashta and ending with Malonaqen is sometimes called the Napatan Period. The later Kings from the twenty-fifth dynasty ruled over Napata, Meroe, and Egypt. The seat of government and the royal palace were in Napata during this period, while Meroe was a provincial city. The kings and queens were buried in El-Kurru and Nuri.[6]

Alara, the first known Nubian king and predecessor of Kashta was not a 25th dynasty king since he did not control any region of Egypt during his reign. While Piye is viewed as the founder of the 25th dynasty, some publications may include Kashta who already controlled some parts of Upper Egypt. A stela of his was found at Elephantine and Kashta likely exercised some influence at Thebes (although he did not control it) since he held enough sway to have his daughter Amenirdis I adopted as the next Divine Adoratrice of Amun there.

Piye

The twenty-fifth dynasty originated in Kush, or (Nubia), which is presently in Northern Sudan. The city-state of Napata was the spiritual capital and it was from there that Piye (spelled Piankhi or Piankhy in older works) invaded and took control of Egypt.[7] Piye personally led the attack on Egypt and recorded his victory in a lengthy hieroglyphic filled stele called the "Stele of Victory." Piye revived one of the greatest features of the Old and Middle Kingdoms, pyramid construction. An energetic builder, he constructed the oldest known pyramid at the royal burial site of El-Kurru and expanded the Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal.[4] Although Manetho does not mention the first king, Piye, mainstream Egyptologists consider him the first Pharaoh of the 25th dynasty.[3][4][5][8] Manetho also does not mention the last king, Tantamani, although inscriptions exist to attest to the existence of both Piye and Tantamani.

Piye made various unsuccessful attempts to extend Egyptian influence in the Near East, then controlled from Mesopotamia by the Semitic Assyrian Empire. In 720 BC he sent an army in support a rebellion against Assyria in Philistia and Gaza, however Piye was defeated by Sargon II, and the rebellion failed.[9]

Shabaka

Shabaka conquered the entire Nile valley, including Upper and Lower Egypt, around 710 BC. Shabaka had Bocchoris of the preceding Sais dynasty burned to death for resisting him. After conquering Lower Egypt, Shabaka transferred the capital to Memphis. Shabaka restored the great Egyptian monuments and returned Egypt to a theocratic monarchy by becoming the first priest of Amon. In addition, Shabaka is known for creating a well-preserved example of Memphite theology by inscribing an old religious papyrus into the Shabaka Stone. Shabaka supported an uprising against the Assyrians in the Israelite city of Ashdod, however he and his allies were defeated by Sargon II.

Shebitku

Recent research by Dan'el Kahn [11] suggests that Shebitku was king of Egypt by 707/706 BC. This is based on evidence from an inscription of the Assyrian king Sargon II, which was found in Persia (then a colony of Assyria) and dated to 706 BC. This inscription calls Shebitku the king of Meluhha, and states that he sent back to Assyria a rebel named Iamanni in handcuffs. Kahn's arguments have been widely accepted by many Egyptologists including Rolf Krauss, and Aidan Dodson [12] and other scholars at the SCIEM 2000 (Synchronisation of Civilisations of the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C.) project with the notable exception of Kenneth Kitchen and Manfred Bietak at present.

Taharqa

Taharqa ushered in one of Ancient Egypt's greatest periods of renaissance. He ruled as Pharaoh from Memphis, but constructed great works throughout the Nile Valley, including works at Jebel Barkal, Kawa, and Karnak.[13] At Karnak, the Sacred Lake structures, the kiosk in the first court, and the colonnades at the temple entrance are all owed to Taharqa and Mentuemhet. Taharqa built the largest pyramid in the Nubian region at Nuri (near El-Kurru).

From the 10th Century BC onwards Egypt's remaining Semitic allies in Canaan (modern Israel, Jordan, Palestinian Territories and Sinai) and southern Aramea (modern southwestern Syria and southern Lebanon) had fallen to the Mesopotamian based Assyrian Empire, and by 700 BC war between the two empires became inevitable. Taharqa enjoyed some success in his attempts to regain a foothold in the Near East by allying himself with various Semitic peoples in the south west Levant subjugated by Assyria. He aided Judah and King Hezekiah in withstanding a siege by King Sennacherib of the Assyrians (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9). There are various theories (disease, divine intervention, Hezekiah's surrender) as to why the Assyrians failed to take the city. However, Sennacherib's annals record Judah was forced into tribute after the siege.[14] Sennacherib drove the Egyptians from the entire region and back into Egypt. After preventing the Egyptians from gaining a foothold in the region, the Assyrians did not return to the area to do battle for another 20 years, being preoccupied by revolts among their Babylonian brethren and also the Elamites, Scythians and Chaldeans.[15] Sennacherib was murdered by his own sons in revenge for the destruction of the rebellious Mesopotamian city of Babylon, a city sacred to all Mesopotamians, the Assyrians included.

His successor, King Esarhaddon, tired of attempts by Egypt to meddle in the Assyrian Empire, began an invasion of Egypt in 671 BC. Taharqa was defeated, and Egypt conquered, with surprising ease and speed by Esarhaddon. Taharqa fled to his Nubian homeland.[14] Esarhaddon describes "installing local kings (i.e., native Egyptians) and governors" and "All Ethiopians (read Nubians/Kushites) I deported from Egypt, leaving not one left to do homage to me". The Assyrian conquest ended the Nubian 25th dynasty in Egypt, and effectively destroyed the Kushite Empire.

However, the Assyrians only stationed their own troops in the north, and the native Egyptian puppet rulers installed by the Assyrians were unable to retain total control of the south of country for long, and two years later (669 BC) Taharqa returned from Nubia and seized control of southern Egypt from the native vassal rulers as far north as Memphis. Esarhaddon set about returning to Egypt to once more eject Taharqa from the south; however, he fell ill and died in the northern Assyrian city of Harran before departing. His successor Ashurbanipal sent a general with a small, well-trained army corps which easily defeated and ejected Taharqa from Egypt once and for all. He died in Nubia two years later. Taharqa remains an important historical figure in Sudan and elsewhere, as is evidenced by Will Smith's recent project to depict Taharqa in a major motion picture.[16] As of 2016, the status of this project is unknown.

Tantamani

His successor, Tantamani, also made a failed attempt to regain Egypt from the Assyrian Empire. He invaded the far south and defeated a native Egyptian prince named Necho, a vassal ruler of Ashurbanipal, taking Thebes in the process. The Assyrians, based in the north, then sent a large army southwards. Tantamani was routed and fled back to Nubia, and the Assyrian army sacked Thebes to such an extent that it never truly recovered. A native Egyptian ruler, Psamtik I, was placed on the throne, as a vassal of Ashurbanipal of Assyria; he was the first ruler of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. In 656 BC, Psamtik I peacefully took control of rebellious Thebes and effectively unified all of Egypt, though it remained subject to Assyria until the Assyrian Empire began to tear itself apart with a brutal series of internal civil wars in the 620's BC. Tantamani and the Nubians were never again to pose a threat to either Assyria or Egypt. However, upon his death, Tantamani was buried with full honours in the royal cemetery of El-Kurru, upstream from the Kushite capital of Napata.[14]

The Twenty-fifth Dynasty ruled for a little more than one hundred years. The successors of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty settled back in their Nubian homeland, where they established a kingdom at Napata (656 - 590 BC), then, later, at Meroë (590 BC - 4th century AD).

Influence

Although the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty controlled Ancient Egypt for only 89 years (from 760 BC to 671 BC), it holds an important place in Egyptian history due to the restoration of traditional Egyptian values, culture, art, and architecture. The 25th dynasty likely influenced Greek visitors.

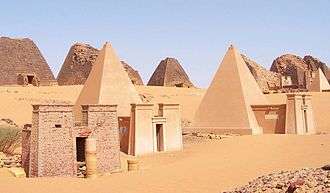

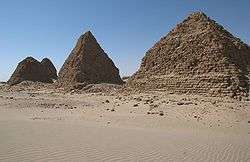

Gallery of images

-

Relief of a High Official, ca. 670-650 B.C.E. 1996.146.3, Brooklyn Museum; This relief's style makes it possible to attribute it to one of the palatial tombs of Dynasty XXV and Dynasty XXVI built by great officials such as Montuemhat, governor of Upper Egypt.

-

Kashta the first King of the twenty fifth dynasty took control of Upper Egypt and installed his daughter Amenirdis I, as Chief Priestess of Amun at Thebes. Above are the names of Amenirdis (left) and Kashta (right).

-

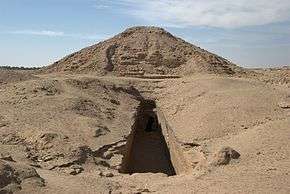

Piye, was a Nubian king who conquered Egypt and brought it under his control. During the twenty fifth dynasty, the new dynasty ruled from Meroe. Here, is his pyramid at Al Kurru, Sudan.

-

Shabaka

-

.jpg)

Shebitku

-

Taharqa in the guise of the Sphinx. Taharqa was the son of Piye.

-

Tantamani

See also

References

- ↑ Török, László (1998). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Leiden: BRILL. p. 132. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

- ↑ Bonnet, Charles (2006). The Nubian Pharaohs. New York: The American University in Cairo Press. pp. 142–154. ISBN 978-977-416-010-3.

- 1 2 Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- 1 2 3 Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York: Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- 1 2 Silverman, David (1997). Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-19-521270-3.

- ↑ Dows Dunham, Notes on the History of Kush 850 BC-A. D. 350, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 50, No. 3 (July - September , 1946), pp. 378-388

- ↑ The Histories. Penguin Books. 2003. pp. 106–107, 133–134,. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa. California, USA: University of California Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-520-06697-9.

- ↑ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ↑ "Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the Napatan Region". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ↑ "The Inscription of king Sargon II of Assyria at Tang-i Var and the Chronology of Dynasty 25," Orientalia 70 (2001), pp.1-18

- ↑ Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 82(2002), p.182 n.24

- ↑ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. pp. 219–221. ISBN 1-55652-072-7.

- 1 2 3 Roux, Georges, Ancient Iraq

- ↑ Aubin, Henry T. (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press, Inc. pp. x, 139–152. ISBN 1-56947-275-0.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (September 7, 2008). "Will Smith puts on 'Pharaoh' hat". Variety. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

Further reading

- G.A. Reisner, "Discovery of the Tombs of the Egyptian XXVth Dynasty", Sudan Notes and Records, 2 (1919), pp. 237–254

- R.G. Morkot, The Black Pharaohs, Egypt's Nubian Rulers, London, Rubicon Press, 2000

External links

- (French) Voyage au pays des pharaons noirs Travel in Sudan : pictures and notes on the Nubian history