Tunes of Glory

| Tunes of Glory | |

|---|---|

|

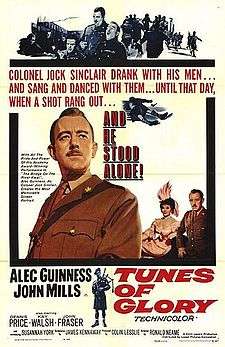

theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Ronald Neame |

| Produced by | Colin Lesslie |

| Written by |

James Kennaway (novel & screenplay) |

| Starring |

Alec Guinness John Mills |

| Music by | Malcolm Arnold |

| Cinematography | Arthur Ibbetson |

| Edited by | Anne V. Coates |

| Distributed by |

United Artists (UK) Lopert Pictures (US) |

Release dates | 20 December 1960 (US) |

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Tunes of Glory is a 1960 British drama film directed by Ronald Neame, based on the novel and screenplay by James Kennaway. The film is a "dark psychological drama" focusing on events in a wintry Scottish Highland regimental barracks in the period following the Second World War.[1] It stars Alec Guinness and John Mills, and features Dennis Price, Kay Walsh, John Fraser, Susannah York, Duncan MacRae and Gordon Jackson.

Writer Kennaway served with the Gordon Highlanders, and the title refers to the bagpiping that accompanies every important action of the regiment. The original pipe music was composed by Malcolm Arnold, who also wrote the music for The Bridge on the River Kwai.[1] The film was generally well received by critics, the acting in particular garnering praise. Kennaway's screenplay was nominated for an Academy Award.

Plot

The film opens in a Battalion officers' mess of an unnamed Highland Regiment in the early post-war era. Major Jock Sinclair (Alec Guinness) announces that this will be his last day as Commanding Officer. Sinclair, who had been in command since the battalion's colonel was killed in action during the North African campaign during the Second World War, is to be replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Basil Barrow (John Mills). Although Major Sinclair led the battalion throughout the remainder of the war, Brigade HQ considered Barrow to be a more appropriate peacetime commanding officer.

Barrow arrives early and observes the battalion's officers (including Sinclair) dancing rowdily. Barrow and Sinclair briefly swap their respective military backgrounds. Sinclair joined the regiment as an enlisted bandsman and rose through the ranks, winning the Military Medal and Distinguished Service Order during the war. Barrow by contrast came to the regiment directly from Oxford University, his ancestors having been colonels of the regiment before him – although he served only for a year with the regiment back in 1933 before being posted to "special duties". When Sinclair humorously tells of the time he was briefly thrown in Barlinnie Prison for being drunk and disorderly (also in 1933), Barrow rather reticently mentions his experience as a prisoner in a Japanese POW camp. Sinclair dismissively assumes Barrow received preferential treatment being an officer ("officer's privileges and amateur theatricals") and sat out the war, but in fact Barrow is deeply psychologically scarred after being tortured by the Japanese but does not tell Sinclair who privately resents the fact that he is being replaced by a "stupid wee man".

Meanwhile Morag (Susannah York), Sinclair's daughter, is observed illicitly meeting an enlisted piper (John Fraser).

Barrow immediately passes several orders designed to instil discipline in the battalion that Sinclair had allowed to slip. Particularly controversial is an order that all officers take lessons in Highland dancing in an effort to make their customary rowdy style more formal and suitable for mixed company. However the unchanged energetic dancing of the officers, led by a drunken Sinclair at Barrow's first cocktail party with the townspeople, incites his anger. An outburst by Barrow only further damages his own authority.

Tensions come to a head when Major Sinclair publicly assaults the uniformed piper he discovers with his daughter – "bashing a corporal" as he put it. Barrow decides an official report must be made, meaning an imminent court-martial, even though he is aware the action will further erode his popularity and authority within the battalion. Barrow is eventually persuaded to back down by Sinclair, who promises Barrow that Sinclair will support him in the future ("We'd make a good team."). The decision further undermines his authority, as Sinclair's promised support never materializes, and the other officers, notably Captain Alec Rattray (Richard Leech), treat him with a renewed lack of respect. The second in command, Major Charlie Scott, with glacial cruelty, implies that it is Sinclair who is really running the battalion, because he forced Barrow to dismiss the charges against him. Alienated now from both Sinclair's clique and the officers who formerly supported him, Barrow commits suicide.

With the colonel's death, Sinclair realises he is to blame. He calls the officers to a meeting and announces plans for a grandiose funeral fit for a field marshal, complete with a march through the town in which all the "tunes of glory" will be played by the pipers. When it is pointed out how out disproportionate the plans are to the circumstances, especially given the manner of the colonel's death, Sinclair insists that it was not suicide but murder. He tells everyone he himself was the murderer and the other senior officers were his accomplices with the exception of the colonel's adjutant.

Sinclair suffers a nervous breakdown and is escorted from the barracks while the officers and men salute as he passes during the closing scene.

Cast

|

|

- Cast notes

- According to an article in the New York Times[2] Alec Guinness wanted to play the role of Barrow, and John Mills wanted to play Sinclair – both initially turned down the film for those reasons. It took a meeting between Guinness, Mills and director Ronald Neame to straighten out why each was best suited for the role they had been offered.[3] However, in his autobiography, John Mills claimed that he brought the script to Guinness, and between them they decided who should play which role.[4] Guinness believed this performance to be among his best.

- Tunes of Glory was Susannah York's film debut. Her opening screen credit reads "and Introducing".[4]

Production

Tunes of Glory was shot at Shepperton Studios in London. Establishing location shots were done at Stirling Castle in Stirling, Scotland. Stirling Castle is the Regimental Headquarters of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders[4] which was the actual location but in fact James Kennaway served with the Gordon Highlanders. Although the production was initially offered broad co-operation to film within the castle from the commanding officer there, as long as it didn't disrupt the regiment's [Argyll's] routine, after seeing a lurid paperback cover for Kennaway's book, that co-operation evaporated, and the production was only allowed to shoot distant exterior shots of the castle.[1]

Director Ronald Neame worked with Guinness on The Horse's Mouth (1958), and a number of other participants were also involved in both films, including actress Kay Walsh, cinematographer Arthur Ibbetson and editor Anne V. Coates.[1]

Awards and honours

James Kennaway, who adapted the screenplay from his novel, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, but lost to Elmer Gantry. It also received numerous BAFTA nominations, including Best Film, Best British Film, Best British Screenplay and Best Actor nominations for both Guinness and Mills.[5]

The film was the official British entry at the 1960 Venice Film Festival, and John Mills won the Best Actor award there.[4] That same year the film was named "Best Foreign Film" by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.[6]

Adaptations

Tunes of Glory was adapted for the stage by Michael Lunney, who directed a production of it which toured Britain in 2006.[7][8]

Home video

Tunes of Glory is available on DVD from Criterion and Metrodome.

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "Tunes of Glory". TCM. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ TCM Notes, which cites the date of the New York Times article as 2 October 1960

- ↑ Robert Osborne, on the Turner Classic Movies broadcast of Tunes of Glory (2 February 2009).

- 1 2 3 4 TCM Notes

- ↑ IMDB Awards

- ↑ AllMovie Guide Awards

- ↑ Brown, Kay. "Tunes of Glory" review ReviewsGate.com

- ↑ "Tunes of Glory" London Theatre Database

External links

- Tunes of Glory at the Internet Movie Database

- Tunes of Glory at the TCM Movie Database

- Tunes of Glory at AllMovie

- Murphy, Robert "Tunes of Glory", Criterion Collection essay