Peace of Amasya

1555

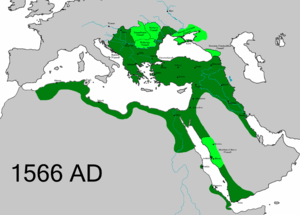

The Peace of Amasya (Persian: پیمان آماسیه; Turkish: Amasya Antlaşması) was a treaty agreed to on May 29, 1555 between Shah Tahmasp of Safavid Iran and Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire at the city of Amasya, following the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1532–1555.

The treaty defined the border between Iran and the Ottoman Empire and was followed by twenty years of peace. By this treaty, Armenia and Georgia were divided equally between the two, with Western Armenia, western Kurdistan, and western Georgia (incl. western Samtskhe) falling in Turkish hands while Eastern Armenia, eastern Kurdistan, and eastern Georgia (incl. eastern Samtskhe) stayed in Iranian hands.[1] The Ottoman Empire obtained most of Iraq, including Baghdad, which gave them access to the Persian Gulf, while the Persians retained their former capital Tabriz and all their other northwestern territories in the Caucasus and as they were prior to the wars, such as Dagestan and all of what is now Azerbaijan.[2][3][4] The frontier thus established ran across the mountains dividing eastern and western Georgia (under native vassal princes), through Armenia, and via the western slopes of the Zagros down to the Persian Gulf.

Several buffer zones were established as well throughout Eastern Anatolia, such as in Erzurum, Shahrizor, and Van.[5] Kars was declared neutral, and its existing fortress was destroyed.[6][7]

The Ottomans, further, gave permission for Persian pilgrims to go to the holy places of Mecca and Medina as well as to the Shia sites of pilgrimages in Iraq.[8]

The decisive parting of the Caucasus and the irrevocable ceding of Mesopotamia to Ottoman Turkey happened per the next major peace treaty known as the Treaty of Zuhab in the mid 17th century.[9]

Another term of the treaty was that the Safavids were required to end the ritual cursing of the first three Rashidun Caliphs,[10] Aisha and other Sahaba (companions of Muhammad); all held in high esteem by Sunnis. This condition was a common demand of Ottoman-Safavid treaties,[11] and in this case was considered humiliating for Tahmasp.[12]

References

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxxi. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- ↑ The Reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520-1566, V.J. Parry, A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730, ed. M.A. Cook (Cambridge University Press, 1976), 94.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO, 31 jul. 2011 ISBN 1598843362 p 698

- ↑ A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010). 516.

- ↑ Ateş, Sabri (2013). Ottoman-Iranian Borderlands: Making a Boundary, 1843–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1107245082.

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO, 31 jul. 2011 ISBN 1598843362 p 698

- ↑ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxxi. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- ↑ Shaw, Stanford J. (1976), History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey, Volume 1, p. 109. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29163-1

- ↑ Феодальный строй, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (Russian)

- ↑ Andrew J Newman (11 Apr 2012). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 46. ISBN 9780857716613.

- ↑ Suraiya Faroqhi (3 Mar 2006). The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It (illustrated, reprint ed.). I.B.Tauris. pp. 36, 185. ISBN 9781845111229.

- ↑ Bengio, Ofra; Litvak, Meir, eds. (8 Nov 2011). The Sunna and Shi'a in History: Division and Ecumenism in the Muslim Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 60. ISBN 9780230370739.