Berakhot (Talmud)

|

Amar Rabbi Elazar

A dramatized cantorial musical rendition of the last passage of Berakhot, which describes how Jewish scholars increase peace. Sung by Cantor Meyer Kanewsky in 1919. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

.jpg)

Berachot (Hebrew: בְּרָכֹות Brakhoth in Talmudic/Classical Hebrew, "Blessings"; also Berachos) is the first tractate (Hebrew: masekhet) of Seder Zeraim ("Order of Seeds"), a collection of the Mishnah that primarily deals with laws relating to plants and farming, hence the name. The tractate Berakhot[1] is the only tractate in Zeraim to have a Gemara (rabbinical commentaries and analysis) from both the Jerusalem Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud. It primarily addresses the rules regarding the Shema (a section of the Torah recited as part of prayer), the Amidah (Silent "standing" prayer), Birkat Hamazon (Grace after Meals), Kiddush (Sanctification ceremony of Shabbat and holidays), Havdalah (ceremony that ends Shabbat and holidays) and other blessings and prayers.

The Shema

The first three chapters of the tractate (Perek I-III) address the subject of the recitation of Shema, a biblical command that constitutes the acceptance of the yoke of Heaven, to be performed twice per day.[1] Topics discussed include when to say it, how to say it and possible exemptions from the fulfillment of this mitzvah ("commandment").

Saying the Shema

Chapter 1

Mishnah א - In the case of the evening Shema, recital begins when the Kohanim enter to eat their terumah (תרומה), which is at nightfall. R'Eliezer says it can be recited until the end of the first watch. He takes "when you lie down" (ובשכבך) to mean the Shema is recited at the time that people lie down to go to sleep, and anyone who will be going to sleep for the night has done so by the end of the first watch. The sages say it can be recited until midnight. And Rabban Gamliel says until the light of dawn. Rabban Gamliel says that whatever mitzvahs the sages said can be performed only until midnight can actually be performed until the light of dawn. The sages said until midnight to distance a person from procrastination and thus transgression. (1:1)

Mishnah ב - The time for reciting the morning Shema is referred to by "when you arise" (ובקומך), and this is when there is enough light to distinguish between blue (תכלת) and white wool. R'Eliezer says between blue and green wool, which would be at a slightly later time. R'Yehoshua says until the end of the first three hours of the day, because it was customary for kings to still be rising until then. The hours referred to are seasonal hours, which are defined by measuring from either the first light of dawn to nightfall or from sunrise to sunset (this is a famous argument) and dividing this into twelve equal parts. Halacha accords with R'Yehoshua and if one recites the Shema after the first three hours, it is as if he is reading from the Torah, which shows that reciting the Shema properly is even greater than reciting words of Torah. The ideal time to recite the Shema is shortly before sunrise so the Shemoneh Esrei can be started at exactly sunrise. This is what it means to join the redemption blessing to the Shemoneh Esrei. (1:2)

Mishnah ג - The position one should assume when reciting the Shema is now discussed. The School of Shammai said the evening Shema should be recited lying down because it is written "when you lie down" (ובשכבך) and the morning Shema should be recited standing because it says "when you arise" (ובקומך). The School of Hillel say it can be said in any position because it is written "when you go on the way" (ובלכתך בדרך). Hillel say that "when you lie down and when you arise" (ובשכבך ובקומך) comes to tell us that it is recited at the time that people are lying down and rising, and not the physical position one should be in while reciting. As in most cases, halakha is in accordance with Hillel. (1:3)

Mishnah ד - In the morning, the two blessings said before the Shema are "Who forms light" (יוצר אור) and "With an abundant love" (אהבת רבה); afterward is the blessing "True and certain" (אמת ויציב). In the evening, the two blessings said before the Shema are "Who brings on evenings" (המעריב ערבימ) and "With an eternal love" (אהבת עולם); afterward are the blessings "True and faithful" (ואמת ואמונה) and "Lay us down" (השכיבו). A short blessing cannot be said in place of a long blessing, and vice versa. Where the sages said to conclude a blessing with "Blessed are You, Hashem" ('ברוך אתה ה), one cannot conclude without it. Where the sages did not say to conclude in that manner, one cannot add it.

Mishnah ה - There is a mitzvah to mention the Exodus from Egypt at night.

The beginning of the second chapter discusses the protocol of exactly how one says the Shema itself. As saying the Shema requires concentration for only the first verse to fulfill the mitzvah, workers may say it even while in a tree (if the tree has many branches) or on a stone wall. However, this does not apply to the Amidah. (2:4)

Exemption

The rest of the second chapter and the entire third chapter discusses exemptions from the Shema, as there are cases where an individual is not required to say it. The second chapter also contains a series of parables regarding Rabban Gamliel to help the reader understand why exemptions may be acceptable. A recently married man is exempt from saying the Shema as he may be anxious about his wedding. (2:5) However, if he is able to properly dedicate himself to God in prayer, he should recite it regardless of the exemption. (2:8) A person who is currently mourning the death of a relative is exempt from saying the Shema and from wearing tefillin. (3:1) Funeral attendees who can see the mourner should not recite the Shema so that the mourner does not feel uncomfortable for not saying it.[2] Women, slaves and children are exempt from the recital of the Shema and from wearing tefillin, but are not exempt from the Amidah, affixing a mezuzah ("doorpost") and Birkat Hamazon.[3]

The Amidah

Chapters 4 and 5 (Perek IV-V) discuss the main prayer known as the Shemoneh Esrei (literally "eighteen"), Amidah (literally "standing"), or just Tefillah ("prayer") in Talmud literature. It originally consisted of eighteen blessings with one later being added by Rabban Gamliel. Today, it is recited three times a day while standing and interruption is forbidden.

Daily Prayers

In the Talmud, there are given two opinions for the source of the two daily prayers and the additional third daily prayer from times of the early Second Temple period on: the daily temple offerings and the three Patriarchs. Prayers were instituted based on the daily offerings in the Jerusalem Temple, and in time and characteristics they parallel them: the daily morning offering, the daily afternoon offering and the additional offering. ″Some explain that this means that prayers were instituted (..) after the destruction of the Temple to replace the offerings. However, these prayers were already extant throughout the Second Temple era (..) Furthermore, there were already synagogues at that time, some even in close proximity to the Temple. The dispute in this case is whether the prayers were instituted to parallel the offerings, or whether the prayers have an independent source, unrelated to the Temple Service.″[4] And Abraham instituted the morning, Isaac the afternoon and Jacob the evening prayer.[5] According to the Talmud Yerushalmi, the Anshei Knesset HaGedola ("The Men of the Great Assembly") learned and understood the beneficial concept of regular daily prayer from personal habits of the forefathers (avoth, Avraham, Isaac, Yaacov) as hinted in the Tanach, and instituted the three daily prayers.[6]

Shacharit can be said until noon; R'Yehudah says until four hours. Mincha is recited in the afternoon. This time period is divided into three sections: mincha gedolah from 6 and a half hours until the end of the twelfth hour; mincha ketanah from 9 and a half hours until the end of the twelfth hour; plag hamincha being half of Mincha ketanah. The ideal time to recite Mincha is at 9 and a half hours, because that is when the mincha offering was performed. Ma'ariv can be said from sunset until midnight (or dawn if necessary). It can even be said shortly before sunset, but in that case one will not fulfill the obligation of reciting the evening Shema in Ma'ariv.

How to say the Amidah

One must say the Amidah every day, but may abbreviate it if he is not familiar with the prayers or an emergency situation comes up. (4:3, Bartenura) One who makes his praying a mechanical task is not praying. When one enters a dangerous situation, he or she should say a short prayer for safety. (4:4) If one is riding a donkey, he must dismount to say the Amidah. If he cannot dismount, he must turn his head towards Jerusalem. If he cannot do that, he must turn his heart to God. This also applies to one travelling on a ship or in a wagon. (4:5, 4:6) Musaf must always be said on the days it is required regardless of whether or not there is a minyan ("quorum") present. (4:7) One should not say the Amidah if he or she is not serious about what he or she is doing. (5:1) The Musaf of Pesach ("Passover") must include a prayer for rain. (5:2)

Leading prayer

If one makes an error while leading a congregation in saying the Amidah, a substitute must pick up where the person left off. (5:3) The prayer leader should not respond "amen" to the kohanim he is leading. (5:4) When one who prays (either for oneself or as a prayer leader) makes a mistake, it is a bad omen for him. If he is a prayer leader, it is also a bad sign for those who appointed him. (5:5)

Blessings for food

Chapter 6 is concerned with the various blessings used before consuming different kinds of food.

Blessings for different types of food

There are special blessings for fruits, vegetables, bread and wine. (6:1) There is also an all-inclusive blessing that can be used if one is unsure of what blessings to say.[7] The all-inclusive blessing should be used for all things which do not directly come from the earth, such as milk, fish and eggs.[8] If one has many different kinds of food of a given type to say blessings for, he or she may choose one food to say the blessing over and the blessings said will suffice for all of the rest of the foods of that kind.[9]

How to make a blessing over food

One blessing over a particular food is sufficient for the entire meal and does not need to be repeated.[10] A communal meal only needs one set of blessings for the entire group, but individuals dining together (albeit not as a group) must say the blessings individually.[11] The food of primary importance is the one which a blessing is said for. However, if one is eating a sandwich, the blessing for the bread would be said rather than the blessing for the sandwich's contents, since bread is never considered being of secondary importance.[12] One who drinks water should make a blessing over the water with the pie blessing.[13]

Birkat Hamazon

Chapter 7 is concerned with Birkat HaMazon, the prayer said by Jews after a meal is completed.

Figs, grapes or pomegranates do not require the full Birkat Hamazon, but rather an abbreviated form.[13] If a group of three or more people eat together, they must say Birkat Hamazon.[14] Women, slaves and minors must not be included when counting for the requirement of three mentioned in the previous mishnah. An olive's quantity of food is sufficient to require saying the prayer.[15] The number of people present does not change the blessing that begins Birkat Hamazon.[16] If three are dining together, they should not separate until they are finished with Birkat Hamazon. If a person is dining alone, he should join another group so that they may say Birkat Hamazon together.[17]

Kiddush and Havdalah

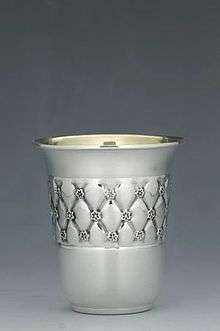

Chapter 8 is concerned with Kiddush, the sanctification of Shabbat and Jewish holidays and Havdalah, the concluding ceremony of Shabbat.

Kiddush

When saying Kiddush, the blessing over the wine (or over the bread) precedes the blessing over the day.[18] One does not need to wash his hands before saying Kiddush but he should wash them after.[19] The towel used to wash one's hands should not be placed on the table, lest it and anything that comes into contact with it be rendered ritually unclean.[20] Following the meal, all the crumbs in the dining room should be thoroughly swept up, then those involved should wash their hands.[20]

Havdalah

If one dines just before the end of Shabbat, one should wait until after having said the blessing for fire (part of the Havdalah ceremony) before saying the Birkat Hamazon.[21] One should not say the Havdalah blessing until the flame is large enough that the person can see reasonably well by its light.[22]

Special blessings

The ninth and final chapter of the Masechet discusses various special blessings that can be made, such as upon coming across a place where a miracle was performed, or upon seeing thunder or lightning or a rainbow.

See also

- Berakhah

- List of Jewish prayers and blessings

- Amidah

- Birkat Hamazon

- Halakha

- Judaism

- Mishnah

- Shema Yisrael

- Talmud

References

- 1 2 (editor-in-chief) Weinreb, Tzvi Hersh; (senior content editor) Berger, Shalom Z.; (managing editor) Schreier, Joshua; (commentary by) Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), Adin ; (2012). [Talmud Bavli] = Koren Talmud Bavli (1st Hebrew/English ed.). Jerusalem: Shefa Foundation. pp. 1, 7 ff. ISBN 9789653015630. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 46. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ (editor-in-chief) Weinreb, Tzvi Hersh; (senior content editor) Berger, Shalom Z.; (managing editor) Schreier, Joshua; (commentary by) Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), Adin ; (2012). [Talmud Bavli] = Koren Talmud Bavli (1st Hebrew/English ed.). Jerusalem: Shefa Foundation. pp. 175 ff. ISBN 9789653015630. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ Tractate Berachoth 26b: the morning sacrifice Tamid, the afternoon Tamid, and the overnight burning of the afternoon offering. The latter view is supported with Biblical quotes indicating that the Patriarchs prayed at the times mentioned. However, even according to this view, the exact times of when the services are held, and moreover the entire concept of a mussaf service, are still based on the sacrifices.

- ↑ “'Anshei Knesset HaGedolah' – Men of the Great Assembly; founded by Ezra in approximately 520 B.C.E.; instituted the "Shemoneh Esray" Prayer” ~ OU Staff. "Anshei Knesset HaGedolah". www.ou.org/judaism-101/. Orthodox Union - February 7, 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 58. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- 1 2 Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 62. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 65. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- 1 2 Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. p. 67. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

- ↑ Blackman, Philip (2000). Mishnayoth Zeraim. The Judaica Press, Ltd. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-910818-00-2.

External links

- Partial text of mishnah Berakhot at Wikisource

- Full text (Hebrew) of mishnah Berakhot at Hebrew Wikisource