Thokoza

| Thokoza | |

|---|---|

|

Aerial view of Thokoza | |

Thokoza  Thokoza  Thokoza

| |

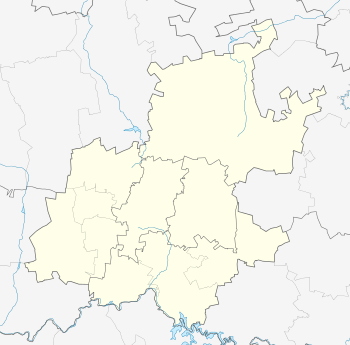

| Coordinates: 26°20′12″S 28°08′48″E / 26.33667°S 28.14667°ECoordinates: 26°20′12″S 28°08′48″E / 26.33667°S 28.14667°E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Gauteng |

| Municipality | Ekurhuleni |

| Established | 1973 |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 9.43 km2 (3.64 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 105,827 |

| • Density | 11,000/km2 (29,000/sq mi) |

| Racial makeup (2011)[1] | |

| • Black African | 99.1% |

| • Coloured | 0.4% |

| • Indian/Asian | 0.1% |

| • White | 0.1% |

| • Other | 0.2% |

| First languages (2011)[1] | |

| • Zulu | 40.2% |

| • Sotho | 21.5% |

| • Xhosa | 18.4% |

| • Northern Sotho | 5.4% |

| • Other | 14.5% |

| Postal code (street) | 1426 |

| PO box | 1421 |

Thokoza is a township south of Johannesburg, South Africa at the location of the now defunct Palmietfontein Airport. It is situated south east of Alberton, adjacent to Katlehong on the East Rand, Gauteng, South Africa. Thokoza is the first black township which was established in the East Rand. During the early 1990s Thokoza was the middle of a civil war between the supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), rival party of the African National Congress (ANC).[2]

History

In 1955, the Germiston and Alberton municipalities swapped land and the latter received part of the land that made up the Natalspruit area, which was needed to form a new black township.[3]:54 From 1958-59, the Alberton municipality begun to develop a new township on the Palmietfontein section.[3]:54 Each plot was to be serviced with a basic water and sewerage infrastructure, with the building of a one bedroom shack and later one, two or three bedroom houses.[3]:54 The new township would be called Thokoza (place of peace).[3]:54 By 1961 all black residents of locations within the Alberton municipality had been moved to the new township after a registration process and the issuing of plot locations.[3]:54–5

All this was in aid of carrying out the introduction of the Apartheid governments Native (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act, which controlled the movement of the black population in the country to certain areas of work and residence. Financially, municipalities were aided in this process by the enactment of two new laws in the 1950s. Bantu Building Workers' Act (1950) which allowed black workers, on low wages, to build the houses and infrastructure and the Bantu Services Levy Act (1952) which paid for the new building work by levying the wages of black employees in the country.[3]:54

From 1961 until 1981, three hostels, Madala, Buyafuthi and Umshayzafe were constructed for migrant labour and situated along Khumalo Road, the main road in the city which stretches for over seven kilometers.[3]:55 Khumalo Street would be named after Jacon Khumalo, a migrant worker from Vryheid, KwaZulu-Natal and who was a community leader in 1960s and who's house is still found along the road.[4] The hostels were created for 2500 men but by the 1980s the popolutation residing in them had risen to as high as 13,000 split along ethnic, social and language groups.[3]:55 This tended to isolated the hostel dwellers from the township dwellers and led to tension in later years.[3]:55 By the late 1960s, crime levels grew in the region as social conditions deteriorated and employment dropped.[3]:58

In 1972, Piet Koornhof, then Minister of Bantu Administration, established the East Rand Administration Board (ERAB) and with that removed 4058ha of Thokoza from the Alberton municipality with the management of the land now under control of the new board and more directly the South African governments apartheid land policies.[3]:58 After 1982, the township would gain municipality status from the East Rand Administration Board.[5] The board would fail to alleviate the shortages of land and housing for the black population region, with most of financial resources provided used to manage the board itself.[3]:58 The population increased from between 27,000 and 48,000 between 1970 and 1975, despite no further land or house being issued.[3]:59 The main reason for the increase in population during this period was development of the Alrode industrial area adjacent to Thokoza that resulted in further employment opportunities.[3]:59 Despite the requests of the ERAB for further funding for development, the South African government failed to provide it.[3]:59–60

On 17 June 1976, Thokoza residents joined in the protests what became known as the Soweto uprising that had started in the township of Soweto the day before, brought about by the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction in local schools, and resulted in a week of violent protests.[3]:58

The 1980s saw the rise of the backyard shack dwellers and informal settlements on open land, with two shacks for every formal house in Thokoza and by 1992, the shacks ratio had doubled.[3]:60 Forced removals would be the option used by local government to try to maintain control of the city, after the introduction of monthly levies to be paid by shack dwellers failed to move them on.[3]:60

By the mid 1980s, rent boycotts and the failure to pay for utility services started, mostly as a protest against the black local government.[3]:61 Soon law and order fell apart, and students, trade unionists, street committees, hostel-dwellers and gangsters filled the vacuum brought about by the lack of political expression by the occupants of Thokoza.[3]:61–2

In 1990, the population had reached 228,000 and the initial infrastructure provided by the Alberton municipality in the 1960s had begun to fail with the lack of water and the failure of sewage systems being the most serious issues.[3]:61

In the early 1990s, prior to the 1994 elections, political tensions developed between the township dwellers and the hostel residents, split by political affiliations, the African National Congress (ANC) or the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).[4] In October 1999, the leaders of both the ANC and IFP met in Thokoza's Khumalo Road, to commemorate at a community-memorial, the 688 people who died during the violence in the early 1990s, and to symbolize a spirit of healing and reconciliation in the community.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Main Place Thokoza". Census 2011.

- ↑ http://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/2011/06/28/thokoza-looks-back-at-its-bang-bang-days

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Marx, Colin; Rubin, Margot (May 2008). "'Divisible Spaces': Land Biographies in Diepkloof, Thokoza and Doornfontein, Gauteng" (PDF). Urban LandMark. p. 136. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- 1 2 ka'Nkosi, Sechaba (24 April 2014). "Khumalo street in East Rand is remembered". South African Broadcasting Commission. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Mashabela, Harry (1988). "Townships of the PWV". South African Institute of Race Relations. p. 184. ISBN 9780869823439. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ Harrison, Philip (2004). "Struggle: Volume 6 of South Africa's top sites". New Africa Books. p. 104. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

.svg.png)