The Lion King (video game)

| The Lion King | |

|---|---|

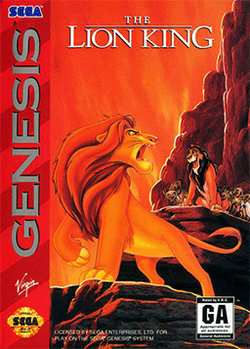

Packaging for the Genesis version | |

| Developer(s) | Westwood Studios |

| Publisher(s) | Virgin Interactive[lower-alpha 1] |

| Distributor(s) | Walt Disney Computer Software |

| Director(s) | Louis Castle |

| Producer(s) |

Louis Castle Patrick Gilmore Paul Curasi |

| Designer(s) | Seth Mendelsohn |

| Programmer(s) |

Rob Povey Barry Green |

| Artist(s) |

John Fiorito Alex Schaeffer Christina Vann Ann-Bettina Colace |

| Composer(s) |

Sega Genesis Matt Furniss Amiga, PC Allister Brimble Super NES Frank Klepacki Dwight Okahara Patrick Collins |

| Platform(s) | Genesis, Super NES, Nintendo Entertainment System, Game Boy, PC, Amiga, Game Gear, Master System |

| Release date(s) |

Super NES, Genesis Amiga

Nintendo Entertainment System

Master System

Game Gear

Game Boy |

| Genre(s) | Platform game |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

The Lion King is a platformer video game based on Disney's popular animated film of the same name. The title was developed by Westwood Studios and published by Virgin Interactive for the Super NES and Genesis in 1994, and was also ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System, Game Boy, PC, Amiga, Master System, and Game Gear. The NES, Master System and Amiga versions were only released in the PAL region, with the NES version in particular being the last game released for the platform in the region. The game follows Simba's journey from a young care-free cub to the battle with his evil uncle Scar as an adult.

Gameplay

The Lion King is a side-scrolling platform game in which players control the protagonist, Simba, through the events of the film, going through both child and adult forms as the game progresses. In the first half of the game, players control Simba as a child, who primarily defeats enemies by jumping on them. Simba also has the ability to roar, using up a replenishable meter, which can be used to stun enemies, make them vulnerable, or solve puzzles. In the second half of the game, Simba becomes an adult and gains access to various combat moves such as scratching, mauling, and throws. In either form, Simba will lose a life if he runs out of health or encounters an instant-death obstacle, such as a bottomless pit or a rolling boulder.

Throughout the game, the player can collect various types of bugs to help them through the game. Some bugs restore Simba's health and roar meters, other more rare bugs can increase these meters for the remainder of the game, while black spiders will cause Simba to lose health. By finding certain bugs hidden in certain levels, the player can participate in bonus levels in which they play as either Timon or Pumbaa to earn extra lives and continues. Pumbaa's stages have him collecting falling bugs and items until either one hits the bottom of the screen or he eats a bad bug, while Timon's stages have him hunting for bugs within a time limit while avoiding spiders.

Development

The sprites and backgrounds were drawn by Disney animators themselves at Walt Disney Feature Animation, and the music was adapted from songs and orchestrations in the soundtrack. In a "Devs Play" session with Double Fine, game designer Louis Castle revealed that two of the game's levels, Hakuna Matata and Be Prepared, were adapted from scenes that were scrapped from the final movie.[1]

The Genesis version of the game does not have background vocals unlike the Super NES version, but the Super NES version has fewer background particles than the Genesis version. This is evident in the Elephant Graveyard and Stampede levels, as well as on the title screen. The MS-DOS version contains background vocals when the game is played with a SoundBlaster sound card. The vocals are missing when the game is using an AdLib sound card due to AdLib's inability to play digital sound.

The Amiga 1200 version of the game was developed in 2 months from scratch in Assembly language by Dave Semmons, who was willing to take on the conversion if he received the Genesis source code. He assumed the game to be programmed in 68000 assembly, since the Amiga and Genesis shared the same CPU family, but turned out to be written in C, a language he was unfamiliar with.[2]

Windows technical issues

The Windows 3.1 version relied on the WinG graphics API, but a series of Compaq Presarios were not tested with WinG, which caused the game to crash while loading.[3] The crashes caused game developers to be suspicious of Windows as a viable platform and instead many stuck with MS-DOS. To prevent further hardware/software compatibility issues, Direct X was created. This also led to the Windows 95 port of Doom to try to regain developers' faith in Windows. This also led to the creation of Microsoft's own consoles that use DirectX: the original Xbox, based on Intel's Pentium III processor, the Xbox 360, based on the PowerPC architecture, and the Xbox One, based on AMD's APU.[4]

Reception

The SNES version of The Lion King sold well, with 1.27 million units sold in the United States alone.[5] The PC version sold over 200,000 copies.[6]

GamePro gave the SNES version a generally negative review, commenting that the game has outstanding graphics and voices but "repetitive, tedious game play that's too daunting for beginning players and too annoying for experienced ones." They particularly noted the imprecise controls and highly uneven difficulty, though they felt the "movie-quality graphics, animations, and sounds" were good enough to make the game worth playing regardless of the game play.[7] They similarly remarked of the Genesis version, "The Lion King looks good and sounds great, but the game play needs a little more fine-tuning ..."[8]

The four reviewers of Electronic Gaming Monthly praised the Game Gear version as having graphics equal to the SNES and Genesis versions and control that is vastly improved over those versions. They scored the game a 7.75 out of 10 average.[9] GamePro wrote that the graphics are not as good as those of the SNES and Genesis versions, but agreed that they are exceptional by Game Gear standards, and praised the Game Gear version for having a much more gradual difficulty slope than the earlier versions.[10] Gameplayers wrote in their November 1994 issue that "even on the easy setting, the game is hard for an experienced player".

The PC version was a subject of controversy due it requiring technical specifications and setup beyond what most of the game's target audience had experience with, which resulted in many people who bought the game finding that they could not make it run.[3][6]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Sega versions were co-published by Sega

References

- ↑ Mike Fahey. "How Westwood Made The Lion King, One Of Gaming's Finest Platformers". Kotaku UK. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ http://www.codetapper.com/amiga/interviews/dave-semmens/

- 1 2 "The 25 Worst Tech Products of All Time". PC World. 26 May 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Kushner, David (2003). Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created An Empire And Transformed Pop Culture. Random House. 89. ISBN 0-375-50524-5.

- ↑ "US Platinum Videogame Chart". The Magic Box. Retrieved August 13, 2005.

- 1 2 Bateman, Selby (April 1995). "Movers & Shakers". Next Generation. Imagine Media (4): 27.

- ↑ "ProReview: The Lion King". GamePro (64). IDG. November 1994. pp. 116–117.

- ↑ "ProReview: The Lion King". GamePro (65). IDG. December 1994. pp. 90–91.

- ↑ "Review Crew:The Lion King". Electronic Gaming Monthly (65). Ziff Davis. December 1994. p. 46.

- ↑ "ProReview: The Lion King". GamePro (65). IDG. December 1994. p. 220.