Bassae

Bassae (Latin: Bassae, Ancient Greek: Βάσσαι - Bassai, meaning "little vale in the rocks"[1]) is an archaeological site in Oichalia, a municipality in the northeastern part of Messenia, Greece. In classical antiquity, it was part of Arcadia. Bassae lies near the village of Skliros, northeast of Figaleia, south of Andritsaina and west of Megalopolis. It is famous for the well-preserved mid- to late-5th century BC Temple of Apollo Epicurius.

Although this temple is geographically remote from major polities of ancient Greece, it is one of the most studied ancient Greek temples because of its multitude of unusual features. Bassae was the first Greek site to be inscribed on the World Heritage List (1986).[2] Its construction is placed between 450 BC and 400 BC.

Temple of Apollo Epikourios

| Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii |

| Reference | 392 |

| UNESCO region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

The temple was dedicated to Apollo Epikourios ("Apollo the helper"). It was designed by Iktinos,[3] architect at Athens of the Parthenon.[1] The ancient writer Pausanias praises the temple as eclipsing all others but the temple of Athena at Tegea by the beauty of its stone and the harmony of its construction.[4] It sits at an elevation of 1,131 metres[1] above sea level on the slopes of Kotylion Mountain.

Construction and decoration

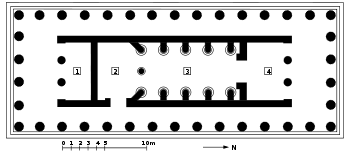

The temple is aligned north-south, in contrast to the majority of Greek temples which are aligned east-west; its principal entrance is from the north. This was necessitated by the limited space available on the steep slopes of the mountain. To overcome this restriction a door was placed in the side of the temple, perhaps to let light in to illuminate the cult statue.

The temple is of a relatively modest size, with the stylobate measuring 38.3 by 14.5 metres[5] containing a Doric peristyle of six by fifteen columns (hexastyle). The roof left a central space open to admit light and air. The temple was constructed entirely out of grey Arcadian limestone[6] except for the frieze which was carved from marble (probably in ancient times colored with paint). Like most major temples it has three "rooms" or porches: the pronaos, plus a naos and an opisthodomos. The naos may have housed a cult statue of Apollo, although it is also surmised that the single 'proto-Corinthian' capital discovered by Cockerell, and subsequently lost at sea, may have topped the single column that stood in the centre of the naos, and have been intended as an aniconic representation of Apollo Borealis. The temple lacks some optical refinements found in the Parthenon, such as a subtly curved floor, though the columns have entasis.[7]

The temple is unusual in that it has examples of all three of the classical orders used in ancient Greek architecture: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.[1] Doric columns form the peristyle while Ionic columns support the porch and Corinthian columns feature in the interior. The Corinthian capital is the earliest example of the order found to date.[1]

It was relatively sparsely decorated on the exterior.[8] Inside, however, there was a continuous Ionic frieze showing Athenians in battle with Amazons and the Lapiths engaged in battle with Centaurs.[9] This frieze's metopes were removed by Charles Robert Cockerell and taken to the British Museum in 1815. (They are still to be seen in the British Museum's Gallery 16, near the Elgin Marbles.[9]) Cockerell decorated the walls of the Ashmolean Museum's Great Staircase and that of the Travellers Club with plaster casts of the same frieze.[10]

Re-discovery and removal by the British

The temple had been noticed first in November 1765 by the French architect J. Bocher, who was building villas at Zante and came upon it quite by accident; he recognized it from its site, but when he returned for a second look, he was murdered by bandits.[11] Charles Robert Cockerell and Carl Haller von Hallerstein, having secured sculptures at Aegina, hoped for more successes at Bassae in 1811; all Haller's careful drawings of the site were lost at sea, however.[12]

The site was explored in 1812 with the permission of Veli Pasha, the Turkish commander of the Peloponnese, by a group of British antiquaries who removed 23 slabs from the Ionic cella frieze and transported them to Zante along with other sculptures. Veli Pasha's claims on the finds were silenced in exchange for a small bribe, and the frieze was bought at auction by the British Museum in 1815. This frieze's metopes were removed personally by Cockerell. (They are still to be seen in the British Museum's Gallery 16.[9]) The frieze sculptures were published in Rome in 1814 and officially, by the British Museum in 1820. Other hasty visits resulted in further publications. The first fully published excavation was not begun until 1836; it was carried out by Russian archaeologists, among which the painter Karl Bryullov. Perhaps the most striking discovery was the oldest Corinthian capital found to date. Some of the recovered artefacts are on display at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

In 1902, a systematic excavation of the area was carried out by the Greek Archaeological Society of Athens under archaeologist Konstantinos Kourouniotis along with Konstantinos Romaios and Panagiotis Kavvadias. Further excavations were carried out in 1959, 1970 and from 1975–1979, under the direction of Nikolaos Gialouris.[1]

Preservation

The temple's remoteness— Pausanias is the only ancient traveller whose remarks on Bassae have survived— has worked to its advantage for its preservation. Other, more accessible temples were damaged or destroyed by war or preserved only by conversion to Christian uses; the Temple of Apollo escaped both these fates. Due to its distance from major metropolitan areas it also has less of a problem with acid rain which quickly dissolves limestone and damages marble carvings.

The temple of Apollo is presently covered in a white tent in order to protect the ruins from the elements. Conservation work is currently being carried out under the supervision of the Committee for the Conservation of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios of the Greek Ministry of Culture, which is based in Athens.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hellenic Ministry of Culture: The Temple of Epicurean Apollo.

- ↑ Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae, World Heritage List.

- ↑ The attribution was noted by Pausanias, 8.41.7ff.

- ↑ Pausanias, 8.41.7 ff.

- ↑ Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae, World Heritage Site.

- ↑ Takis Theodoropoulos, "The temple of Apollo the Helper - Heritage", UNESCO Courier, January 1996.

- ↑ Dinsmoore 1933:207

- ↑ William Dinsmoor made a detailed case for recognising former pedimental sculptures from Bassae, looted by Romans, in three pedimental figures of Niobids discovered at various times in the later nineteenth century on the site of the Gardens of Sallust, Rome (Dinsmoor, "The Lost Pedimental Sculptures of Bassae" American Journal of Archaeology 43.1 (January-March 1939:27-47).

- 1 2 3 Bassae Sculpture, British Museum.

- ↑ Beazley Archive

- ↑ William Bell Dinsmoor, "The Temple of Apollo at Bassae" Metropolitan Museum Studies 4.2 (March 1933:204-227) p 204, notes Bocher's drawings, acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1914.

- ↑ Dinsmoor 1933:205.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae. |

- Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Bassae

- Hellenic Ministry of Culture: Temple of Apollo Epikourios

- Excavation of the Temple

- UNESCO: Temple of Apollo Epicureus at Bassae

Coordinates: 37°25′47″N 21°54′01″E / 37.42972°N 21.90028°E