Tegetthoff-class battleship

SMS Tegetthoff | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Tegetthoff class |

| Builders: |

|

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Radetzky class |

| Succeeded by: | Ersatz Monarch class |

| In commission: | 1912–18 |

| Completed: | 4 |

| Lost: | 2 |

| Retired: | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 152.20 m (499 ft 4 in) |

| Beam: | 27.30 m (89 ft 7 in) |

| Draft: | 8.90 m (29 ft 2 in) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) design speed |

| Range: | 4,200 nmi (7,780 km; 4,830 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) with 2,000 tons of coal |

| Complement: | 1,087 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

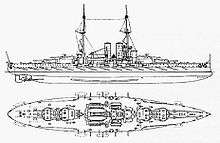

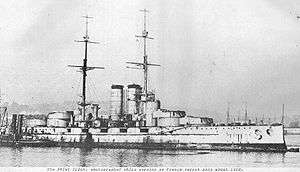

The Tegetthoff class (sometimes erroneously named the Viribus Unitis class) was the sole class of dreadnought battleship built for the Austro-Hungarian Navy. Four ships were built, Viribus Unitis, Tegetthoff, Prinz Eugen, and Szent István. Three of the four were built in Trieste; Szent István was built in Fiume, so that both parts of the Dual Monarchy would participate in the construction of the ships. The smaller size of the shipyards in Fiume meant that Szent István was built three years after her sisters, with slightly different characteristics.

The first three ships, Viribus Unitis, Tegetthoff, and Prinz Eugen were joined by their sister in 1915, when they bombarded Italian installations at Ancona. The Tegetthoffs attempted to sortie through the Otranto Barrage with the support of lighter ships in 1918, but failed after Szent István was sunk. In 1918, Viribus Unitis was transferred to Yugoslavia, and sunk the next day by Italian frogmen. Tegetthoff and Prinz Eugen were surrendered to Italy and France, respectively.

Characteristics

Dimensions

The ships had an overall length of 152 metres (498 ft 8 in), a beam of 27.90 metres (91 ft 6 in), and a draught of 8.70 metres (28 ft 7 in) at deep load. They displaced 20,000 tonnes (19,684 long tons) at load and 21,689 tonnes (21,346 long tons) at deep load.[2]

Propulsion

The propulsion consisted of four Parsons steam turbines, each of which was housed in a separate engine-room. The turbines were powered by twelve Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines were designed to produce a total of 27,000 shaft horsepower (20,134 kW), which was theoretically enough to attain her designed speed of 20 knots (23 mph; 37 km/h), but no figures from her speed trials are known to exist.[3] She carried 1,844.5 tonnes (1,815.4 long tons) of coal, and an additional 267.2 tonnes (263.0 long tons) of fuel oil that was to be sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate.[2] At full capacity, she could steam for 4,200 nautical miles (7,800 km) at a speed of 10 knots (12 mph; 19 km/h).[4]

Armament

Each ship was armed with twelve 305-millimetre (12 in)/45-caliber K 10 guns in four triple turrets mounted on the center-line, forward and aft of the superstructure. Their secondary armament consisted of twelve 150-millimetre (5.91 in)/50 K 10 guns mounted in casemates amidships. Eighteen 70-millimetre (3 in)/50 K 10 guns were mounted on open pivots on the upper deck above the casemates. Three more 66-mm K 10 guns were mounted on the upper turrets for anti-aircraft duties. Four 530-millimetre (21 in) submerged torpedo tubes were fitted, one each in the bow, the stern, and each side; twelve torpedoes were carried.[2]

Armor

The waterline armour belt of the Tegetthoff class measured 280 millimetres (11 in) thick between the midpoints of the fore and aft barbettes and thinned to 150 millimetres (5.9 in) further towards the bow and stern, but did not reach either the bow or the stern. It was continued to the bow by a small patch of 110–130-millimetre (4–5 in) armour. The upper armour belt had a maximum thickness of 180 millimetres (7.1 in), but it thinned to 110 millimetres (4.3 in) from the forward barbette all the way to the bow. The casemate armour was also 180 millimetres (7.1 in) thick. The sides of the main gun turrets, barbettes and main conning tower were protected by 280 millimetres (11 in) of armour, except for the turret and conning tower roofs which were 60 to 150 millimetres (2 to 6 in) thick. The thickness of the decks ranged from 30 to 48 millimetres (1 to 2 in) in two layers. The underwater protection system consisted of the extension of the double bottom up to the lower edge of the waterline armour belt, with a thin 10-millimetre (0.4 in) plate acting as the outermost bulkhead. It was backed by a torpedo bulkhead that consisted of two layered 25-millimetre plates.[5] The total thickness of this system was only 1.60 metres (5 ft 3 in) which made it incapable of containing a torpedo warhead detonation or mine explosion without rupturing.[6]

Variations

Szent István, built at Fiume, differed from her half-sisters mainly in her machinery. She only had two shafts and two turbines, unlike the four shaft arrangement of the other ships of her class. External differences included a platform built around the fore funnel which extended from the bridge to the after funnel and on which several searchlights were installed. A further distinguishing feature was the modified ventilator trunk in front of the mainmast. She was the only ship of her class not to be fitted with torpedo nets.[7]

Ships

| Name | Namesake | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viribus Unitis (ex-Tegetthoff) | "With United Forces" (personal motto of Emperor of Austria) |

Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino, Trieste | 24 July 1910 | 24 June 1911 | 5 December 1912 | Handed to Yugoslavia, 31 October 1918 Sunk by Italian frogmen, 1 November 1918 |

| Tegetthoff | Vizeadmiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff | 24 September 1910 | 21 March 1912 | 14 July 1913 | Broken up at La Spezia, 1925 | |

| Prinz Eugen | Prince Eugene of Savoy | 16 January 1912 | 30 November 1912 | 8 July 1914 | Sunk as target, 1922 | |

| Szent István (ex-János Hunyadi) |

Szent István király (King Stephen I of Hungary) | Ganz Danubius, Fiume | 29 January 1912 | 17 January 1914 | 13 December 1915 | Torpedoed and sunk off Otranto, 10 June 1918 |

Construction

The Austro-Hungarian government ordered the construction of a new fleet in 1908, following the announcement of the start of construction of the first dreadnought for the Regia Marina (the Italian navy), Dante Alighieri. The ships of this class were among the first ships to utilize triple gun turrets for their main armament, the first one being the Italian battleship Dante Alighieri, which the Austro-Hungarian ships were supposed to act against in a war; as with the Italian ship, this choice made it possible to deliver a heavier broadside than other dreadnoughts of a similar size. The triple turrets were built at the Škoda Works, in Plzeň, Bohemia, and were available at short notice because Škoda were already working on a triple turret design ordered by Russia.[8]

The first unit was to bear the name of Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, an Austrian naval admiral of the 19th century, but Franz Joseph I wanted it to be named with his personal motto, Viribus Unitis (Latin for "With united forces"). In any event, the class name remained Tegetthoff.[9]

The first three ships were built at the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino yard, Trieste.[10] As a condition of agreeing to the construction and financing of the new fleet, the Hungarian parliament insisted that one of the battleships be built at the Hungarian facility, the Danubius yard at Fiume. However, the Danibius shipyard had until then never built anything larger than a destroyer. So construction was delayed as the yard was extended in preparation for the dreadnought. For this reason the final ship, delivered seventeen months late, was given a Hungarian name: Szent István ("Saint Stephen", after Stephen I, the first king and patron saint of Hungary.[11]

Service history

World War I

The assistance of the Austro-Hungarian fleet was called upon by the German Mediterranean Division, which consisted of the battlecruiser SMS Goeben and light cruiser SMS Breslau.[12] The German ships were attempting to break out of Messina, where they had been coaling prior to the outbreak of war—British ships had begun to assemble off Messina in an attempt to trap the Germans. By this time, the Austro-Hungarians had not yet fully mobilized their fleet, though the three Radetzkys and three Tegetthoffs, along with several cruisers and smaller craft, were available. The Austro-Hungarian high command, wary of instigating war with Great Britain, ordered the fleet to avoid the British ships, and only to support the Germans openly while they were in Austro-Hungarian waters. On 7 August, when the Germans broke out of Messina, the Austro-Hungarian fleet, including the Tegetthoff-class battleships, sailed as far south as Brindisi, before returning to port.[13]

After the breakout, the Austro-Hungarian navy saw very little action, spending much of its time in its base at Pola (now Pula, Croatia). The navy's general inactivity was partly caused by a lack of coal, which became a problem as the war progressed, and partly by a fear of mines in the Adriatic (which also kept the Italian navy in port for most of the war). They did, however, leave Pola to bombard Ancona in May 1915. On 23 May 1915, four hours after the Italian declaration of war reached the main Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola, the members of the Tegetthoff class and the rest of the fleet departed to bombard the Italian coast.[14] The Austro-Hungarian ships bombarded the important naval base at Ancona,[15] and later the coast of Montenegro, without opposition; by the time Italian ships arrived on the scene, the Austro-Hungarians were safely back in Pola.[16]

Otranto Raid

In 1918 Admiral Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya became rear admiral of the fleet, and he determined to use the fleet to attack the Otranto Barrage. On 8 June 1918 he took Viribus Unitis and Prinz Eugen south with a small supporting flotilla; on the evening of 9 June, Szent István and Tegetthoff followed. In trying to make maximum speed in order to catch up, Szent István's turbines started to overheat and speed had to be reduced to 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). When an attempt was made to raise more steam in order to increase to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) Szent István produced an excess of smoke, attracting the attention of a pair of patrolling Italian torpedo boats at 3.20 a.m. on 10 June. MAS-21 attacked Tegetthoff, but one of her torpedoes failed to leave the launch tube and the other failed to explode. MAS-15 however hit Szent István with two torpedoes at 3:31 a.m. Tegetthoff returned to the scene to take Szent István in tow. An attempt to beach the ship on nearby Molat Island (northwest of Zara) was considered, but the ship was taking on too much water. At 6:12 am, with the pumps unequal to the task, Szent István capsized, taking 89 of her crew with her. The last half-hour of the sinking was filmed in stages from Tegetthoff .[17] (It was one of only two battleship sinkings on the high seas to ever be filmed, the other being that of the British battleship HMS Barham in World War II.) Fearing further attacks by torpedo boats or destroyers from the Italian navy, his element of surprise now compromised, Admiral Horthy called off the attack and the fleet returned to base for the remainder of the war.[18]

Post-war

After it was clear that Austria-Hungary had lost World War I, the Austrian government decided to give Viribus Unitis, along with much of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, to Yugoslavia, the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. This move would have avoided handing the fleet to the Allies, since the new state had declared neutrality. Following the transfer, she was renamed Yugoslavia.[1]

On 1 November 1918, the transfer being still unknown, two men of the Regia Marina, Raffaele Paolucci and Raffaele Rossetti, rode a primitive manned torpedo (nicknamed the Mignatta or "leech") into the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola. Using limpet mines, they attacked Viribus Unitis and the freighter Wien.[19]

Traveling down the rows of Austrian battleships, the two men encountered Viribus Unitis at around 4:40 am. Rossetti placed one canister of TNT on the hull of the battleship, timed to explode at 6:30 am. He then flooded the second canister, sinking it on the harbor floor close to the ship. The men had no breathing sets, and therefore had to keep their heads above water. They were discovered and taken prisoner just after placing the explosives under the battleship's hull. The Italians did not know that the Austrian government had handed over Viribus Unitis, along with most of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, to Yugoslavia. They were taken aboard Viribus Unitis, where they informed her new captain of what they had done but did not reveal the exact position of the explosives.[19] Vuković then arranged for the two prisoners to be taken safely to the sister ship Tegetthoff, and ordered the evacuation of the ship. But the explosion did not happen at 6:30 as predicted and Vuković, believing mistakenly that the Italians had lied, returned to the ship with many sailors. When the mines exploded shortly afterwards at 6:44, the battleship sank in 15 minutes; Vuković and 300–400 of the crew went down with her. Following the explosion,[19]

The second explosive canister, lying on the bottom, exploded close to the Austrian freighter Wien, resulting in her sinking.[19]

The two Italians were interned for a few days until the end of the war and were honored by the Kingdom of Italy with the Gold Medal of Military Valor.[20][21]

On 4 November Italian troops entered Pola and seized Tegetthoff and Prinz Eugen. The Italians kept Tegetthoff for their own use. She was featured in the movie Eroi di nostri mari ("Heroes of our seas") about the sinking of Szent István.,[4] and was broken her up in 1924 following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. Prinz Eugen became French property. They removed the main armament for inspection and used the ship to test aerial bombardment attacks. She was finally used as a target ship by the battleships Paris, Jean Bart, and France, and sunk in the Atlantic.[4]

See also

- List of ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy

- List of battleship classes

- Lists of ship launches in: 1911, 1912, and 1914

- Lists of ship commissionings in: 1912, 1913, 1914, and 1915

- Lists of shipwrecks in: 1918 and 1922

References

- 1 2 Sokol, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Sieche 1991, p. 133.

- ↑ Sieche 1991, pp. 133, 140.

- 1 2 3 Sieche 1985, p. 334.

- ↑ Sieche 1991, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Sieche 1991, p. 135.

- ↑ Sieche 1991, p. 132.

- ↑ Preston, p. 62.

- ↑ Petković, p. .

- ↑ Myszor, Oskar. "Battleships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy". Austria-Hungary: Major Warships. Historical Handbook of World Navies. Retrieved 27 July 2010. Archived August 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sieche 1991, p. 116.

- ↑ Halpern, p. 53.

- ↑ Halpern, p. 54.

- ↑ Halpern, p. 144.

- ↑ DANFS Zrinyi.

- ↑ Hore, Battleships, p. 180.

- ↑ Battleship Szent Istvan sinks in WW1 on YouTube

- ↑ Sokol, pp. 134–135.

- 1 2 3 4 Warhola, Brian (January 1998). "Assault on the Viribus Unitis". Old News. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ "Gold Medal for Rossetti". Magggiore G.N. (in Italian). marina.difesa.it. Retrieved 29 June 2010. Archived June 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Gold Medal for Paolucci". Tenente medico (in Italian). marina.difesa.it. Retrieved 29 June 2010. Archived June 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

Bibliography

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7. OCLC 57447525.

- Hore, Peter (2006). Battleships. London: Lorena Books. ISBN 978-0-7548-1407-8. OCLC 56458155.

- Petković, Dario (2004). Ratna mornarica Austro-Ugarske monarhije: brodovi u K. U. K. Kriegsmarine s prijelaza iz 19. u 20. stoljeće do kraja Prvog svjetskog rata (Biblioteka Histria Croatica ed.). Pula, Croatia: C.A.S.H. ISBN 978-953-6250-80-6.

- Preston, Anthony (2002). World's Worst Warships. London: Conway's Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-754-2.

- Sieche, Erwin (1985). "Austria-Hungary". In Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8. OCLC 12119866.

- Sieche, Erwin F. (1991). "S.M.S. Szent István: Hungaria's Only and Ill-Fated Dreadnought". Warship International. Toledo, OH: International Warship Research Organization. XXVII (2): 112–146. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Sokol, Anthony (1968). The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 462208412.

Other sources

- "Zrinyi". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

Further reading

- Aichelburg, Wladimir (1981). Die "Tegetthoff"-Klasse: Österreich-Ungarns grösste Schlachtschiffe. München: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 978-3-7637-5259-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tegetthoff class battleships. |

- Computer model of Viribus Unitis

- 30.5 cm/45 (12") & K10 Škoda, at NavWeaps site (accessed 2016-08-31)