Tamraparni

Tamraparni (Tamil/Sanskrit) is an ancient name of the river proximal to Tirunelveli of South India and Puttalam of Western Sri Lanka.[1] A toponym, "Tamraparniyan" is eponymous with the socio-economic and cultural history of this area and its people. Movement of people across the Gulf of Mannar during the early Pandyan and Anuradhapura periods, between the Tamilakam coasts of the river and Northwest Sri Lanka, led to the shared application of the name for the closely connected region.[2] The entire island of Sri Lanka itself came to be known in the ancient world as "Tamraparni". It is a rendering of the original Tamil name Tān Poruṇai of the Sangam period, "the cool river Porunai".[3][4]

Etymology

From the Tamilakam era, the area of the Tamraparni river, in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, has had name modifications,[3] from the original Tān Poruṇai river in the Eṭṭuttokai anthlogy, meaning "the cool river Porunai", to Tān Poruṇdam then Tamira Porunai, to Tamraparni then Tambraparni and now called Thamirabarani River.[1][3][3][4][5] A meaning for the term following its derivation became "copper-colored leaf", from the words Thamiram (copper/red) in Tamil/Sanskrit and parani meaning leaf/tree, translating to "river of red leaves".[2][5] According to the Tambraparni Mahatmyam, an ancient account of the river from its rise to its mouth, a string of red lotus flowers from sage Agastya at Agastya Malai, Pothigai hills, transformed itself into a damsel at the sight of Lord Siva, forming the river at the source and giving it its divine name.[6] At Pothigai, Agastya taught Tamil grammar and learned the Tamil language from deities.[7][8][9] The shrine to Agastya at the Pothigai hill source of the river is mentioned in both Ilango Adigal's Silappatikaram and Chithalai Chathanar's Manimekhalai epics.[10] Similarly, the Sanskrit plays Anargharāghava and Rajasekhara's Bālarāmāyaṇa of the ninth century refer to a shrine of Agastya on or near Adam's Peak, the tallest mountain in Sri Lanka, from whence the river Gona Nadi/Kala Oya flows into the Gulf of Mannar's Puttalam Lagoon.[11] Other name derivations eventually applied to the entire island of Sri Lanka include the Pali term "Tambapanni", "Tamradvipa" of Sanskrit speakers and "Taprobana" and "Taprobane" of ancient Greek and Roman cartographers.[2][3][12] Etymologically related are the terms "Tamraparna" and "Tambarattha".[13] Robert Knox reported from his 20 years of captivity on the island in the hills that "Tombrane" is a name of the Sri Lankan Tamil people for God in Tamil, which they often repeated as they lifted up their hands and faces towards Heaven".[14]

In literature

"Tamraparni" as a toponym is historically related to the Early Pandyan Kingdom. The region south of Tirunelveli, the citadel of the Pandyan kingdom around the Tān Poruṇai river in Tamil Nadu, was referred to as Tamraparna by extension in the ancient period; Korkai, the kingdom's capital and the epicentre of the pearl trade, was located at the river's mouth.[15] Referring to pearls, Kautilya in his Arthasastra speaks of "Thamro Par nika, that which is produced in the Tamraparni", and notes the Pandya country is famed for its gems and pearls, describing Tamraparni as “a large river, which went to meet and traverse the sea (samudram avaghate) containing the row of islands”.[16] In the grammar anthology Tolkāppiyam, the Chera king Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai, a contemporary of Pandyan king Nedunjeliyan II c. 135 AD, is mentioned in the phrase honouring the Lord of the river Tān-Poruṇai thus, Vitar-c-cilai poritta ventan vali, Pun-tan porunai-p-poraiyan vali, Mantaran ceral mannavan vali which describes "Long live the king who engraved in the hill, Long live the lord of the river Porunai filled with flowers and cool water, Long live the King Mantaran Chera".[17] Varahamihira's Brihat Samhita mentions the river Tamraparni, pearls whereof are said to have been slightly copper-coloured or white and bright.[18] Kālidāsa in Raghuvaṃśa praises the pearl fisheries of the river Tamraparni in South India, while giving details that an Ikshvaku king had conquered the Pandyas by carrying successful arms up to the mouth of the river.[19]

"Tamraparni" is, according to 5th century legends of Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa, the name of the area invaded in Western Sri Lanka by the banished Vijaya of Vanga, bringing with him Pandyan queens.[12] Following his marriage to the Yakkha (Yaksha) queen Kuveni, the "lady of Tamraparni", he entered the royal house of Pandya through another marriage. The name Tamraparni, already in use by Tamil inhabitants of the island, was adopted in Pali as Tambapanni.[22] Later in 543 BC, the invaded island area was made Vijaya's "capital" that he called the Kingdom of Tambapanni, of a country north of the island, Rajarata. The point on the Gulf of Mannar, near Chilaw/Mannar and north of Puttalam on the west coast, opposite the mouth of the Tamraparni River in Tirunelveli, is where it was established.[3][5] On this west coast was where the Queen of Mannar and North Western Sri Lanka, Alli Arasani, the daughter of a Pandyan king, was paid tribute with pearls fished by Tamil Paravas, detailed in Alliyarasaninataka and Alli Arasani Malai, which she used to trade Arabian horses, at Kudiramalai.[23][24] The island's Pandyan connection grew annually, as Vijaya sent his Pandyan father-in-law a large variety of beryls, chanks and pearls worth 2 lakhs as gifts, and princes of the dynasty such as Panduvasdeva and Pandukabhaya of Anuradhapura built reservoirs for irrigation on the island using ideas from the people of Tirunelveli's Tamraparni river and Madurai coasts.[5] Puttalam served as a second capital to kings of the Jaffna kingdom, who directed their energies towards consolidating its economic potential by maximising revenue from a lucrative pearl fishing industry developed there.[25] The Divyāvadāna or "Divine narratives" a Sanskrit anthology of Buddhist tales from the 2nd century, calls Sri Lanka "Tamradvipa" and gives an account of a merchant's son who met Yakkhinis, dressed like celestial nymphs (gandharva), in Sri Lanka.[12] A Pali story of the Jataka tales from the same period renders Sri Lanka's name as "Tambapanni"; regions of Sri Lanka such as Nagadipa, Ratnadipa, Lankadipa, Giridipa, Ojadipa, Varadipa, Mandadipa and river Kalyani too are mentioned in various tales.[12] The Valahassa Jataka relates the story of the arrival of five hundred shipwrecked merchants, from Varanasi, to the prosperous port town and Yakkha capital of Sirisavatthu in "Tambapannidipa", where the ancient Yakkha inhabitants were slaughtered by Vijaya and his followers.[26] In Hindu tradition, the founding Yakkha (Yaksha) king Kubera, son of Visravas and nephew of Agastya, ruled the gold city of Lanka before being usurped by his half brother Ravana; Kubera is worshipped as the Hindu god of wealth. Kubera was incorporated into Buddhism with the patronym Vaiśravaṇa (Sanskrit) / Vessavaṇa (Pali) / Vesamuni (Sinhala), meaning "Son of Vaisravas", and syncretised as one of the religion's Four Heavenly Kings. These mentions corroborate writers of the period in relating Tambapanni island as a "fairyland" inhabited by Yakkhinis or "she demons" and the story of Kuveni.[12]

"Listen as I now recount the isle of Tamraparni below Pandya-desa and KanyaKumari, gemmed upon the ocean. The gods underwent austerities there, in a desire to attain greatness. In that region also is the lake of Gokarna...Pulastya said... Then one should go to Gokarna, renowned in the three worlds. O Indra among kings! It is in the middle of the ocean and is worshipped by all the worlds. Brahma, the Devas, the rishis, the ascetics, the bhutas (spirits or ghosts), the yakshas, the pishachas, the kinnaras, the great nagas, the siddhas, the charanas, the gandharvas, humans, the pannagas, rivers, ocean and mountains worship Uma's consort there". Mahabharata. Volume 3. pp. 46-47, 99.

Vyasa, Mahabharata. c.401 BCE. Corroborating the map of Ptolemy drawn four hundred years later, this text also elaborates on two ashrams of the Siddhar Agastya in the region, one near the bay and another atop the Malaya mountain range.[27]

In the Mahābhārata (3:88) written by Vyasa, a Sanskrit passage on the words of Saptarishi Pulastya (Visravas and Agastya's father) relates to the island and Hindu worship at the Koneswaram temple of Trincomalee, describing indigenous and continental pilgrims across the island, including the shrine, before the Anuradhapura period. "Listen, O son of Kunti, I shall now describe Tamraparni. In that asylum the gods had undergone penances impelled by the desire of obtaining salvation. In that region also is the lake of Gokarna, celebrated over the three worlds...".[27]

In Valmiki's Ramayana, "Tamraparni" is related "Search the empire of the Andhras, the sister nations three, Cholas, Cheras and the Pandyas dwelling by the southern sea. Pass Kaveri's spreading waters, Malaya's mountains towering brave, seek the isle of Tamraparni, gemmed upon the ocean wave!"[28]

The Puranas mention Tamraparna/Tamraparni interchangeably as one of nine divisions of Bharatavarsha, the greater Indian subcontinent, and as the river sourced from the Kulacala hill of the Malaya mountains in the Pandyan country of Dravida, visited by Balarama, flowing through sandalwood regions, famous for pearls and counch, fit for Śrāddha offerings, sacred to Pitrs, flows towards the southern ocean, at its confluence with the ocean, it produces conches, shells and pearls.[29]

Paramatthavinicchaya's author Anuraddha, according to its colophon, was a monk born in Kanchipuram who lived during the time of writing the poem in Tanjanagara of "Tambarattha", while Buddharakkhita states in Jinalankara that Anuraddha had a high reputation among the learned men of Coliya-Tambarattha.[13]

Bringing business prospects with them to Manadu's sandy tracts of land on the south bank of Tamraparni river were the Tirunelveli Nadar-Shannars, the royal vassal of Villavar bow-men Tamils who, like their related communities the Ezhava Channars and Tiyyas of Kerala, descend from Shandrar emmigrants from Jaffna and other districts of Northern Sri Lanka, called "Ila-kulattu Shanar", in Sekkizhar's Periya Puranam.[30][31] These land deeds were granted to them by early Pandyan royals; Nadar tradition holds that these Tamils are heirs of the Pandyan kingdom. Migrating cyclically from the early classical rule of the Three Crowned Kings, their movement led to socio-economic exchange as agricultural labourers (Nadar climber), aristocrats (the Nadan (Nadar subcaste)), Jaffna seednut palmyra and jaggery cultivators, toddy tappers and proponents of the Kalaripayattu Dravidian martial arts moved and settled south of the river Tamraparni.[30]

The name "Eelam" remained in early classical use in Tamilakam, alongside the Tamil-Sanskritized "Tamraparni", as the name of Sri Lanka.[32] Uruttirangannanar's Paṭṭiṉappālai uses this Dravidian term for the island and its inhabitants, a term used exclusively in reference to its palm tree toddy from the beginning of the common era to the medieval period.[32] In Manimekhalai, smaller islands of North Sri Lanka are identified, and the term "Ratnadipa" or "Jewel Island" is used as an alternative to "Tamraparni", for Sri Lanka's main island.[32]

At the Tamraparni river's source in Tirunelveli, Tamil was created by Agastya, according to Kamban and Villiputturar, while Kancipuranam and Tiruvilaiyatarpuranam detail that Siva taught Agastya Tamil there.[35] Tamil Hindu tradition holds that the deities Siva and Murugan taught Agastya the Tamil language, who then constructed a Tamil grammar - Agattiyam - at Pothigai mountains.[7][8][9]

Agastya's shrine on Pothigai Hills at Tamraparni river's source is important in the context of the Hindu Ramayana according to the Manimekhalai, which is the first Tamil literature to mention Agastya, while simultaneously conceiving and anticipating South India (Tamilakam), Sri Lanka and Java as a single Buddhist religious landscape.[36] The author of the Silappatikaram, utilizing the word "Potiyil" for the hills, hails the southern breeze that emanates from the hills that blows over the kingdom of the Pandyans of Madurai and Korkai that own it. The Manimekhalai concurrently describes a river flowing on the slope of Pothigai mountains where Buddhist monks observed meditation.[37] Tamil Buddhist tradition which developed in Chola literature, such as in Buddamitra's Virasoliyam, states Agastya learnt Tamil from the Bodhisattva deity Avalokitesvara; the Chinese traveler Xuanzang had recorded the existence of a temple dedicated to Avalokitesvara at Pothigai hills (Tamraparni's source).[7][8] In fellow Sangam work Kuṟuntokai of the Eṭṭuttokai anthology, a Buddhist vihara under a Banyan tree is described at the top of Pothigai. A comment that God had disappeared from the mountain was found in Ahananuru, from whose inaccessible top the stream of clear waters flows down with noise in torrents, and the fact that old men assembled and played dice in the dilapidated temple is described in Purananuru.[38][39] Kapilar and Nakkirar's text Purananuru too mention Tān Poruṇai river in the context of Lanka; in this literature corpus Lanka, a province of Tamilakam once lay close to the estuary of the river before a huge deluge, most likely a tsunami, separated Lanka with a broad channel from whence it has remained the island of Sri Lanka.[1][40]

Tamraparni is mentioned in the Edicts of Asoka, as one of the areas of Buddhist proselytism in the 3rd century BCE:

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni)." (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

Tamraparni in the edicts was the name by which ancients referred to Sri Lanka.[41]

"Tamraparniya" is a name given to one of the early Buddhist schools that developed in Asia - the nikāya school predecessor of Theravada Buddhism and its monastic divisions of Sri Lanka.[42] Theravada doctrines descend from the "school of Tamraparniya", which translates to "the Sri Lankan lineage".[42] In Mahanidessa of the Theravada Buddhist Pali Canon in the first century BC, a geographical list notes Tamraparni island (Tambapanni) as being on an important, spiritual sea route from Tamali to Java, and concurrently, this list of sea voyages that includes the island is mentioned in the Burmese Theravada literature Milinda Panha of the same time period.[43] The term Tamraparniya grew in popularity in South India to denote the Sri Lankan sects. Vasubandhu writing in the 4th century in the Sanskrit Abhidharmakośakārikā on Buddhism mentions the Tamraparniya-nikaya.[44] From this Tamraparniyan school grew subdivisions of Theravada, developed in Sri Lanka at monasteries in Anuradhapura, and sectarianism between them was common. One was at the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya, where Buddhadatta, Buddhaghosa and Dhammapala taught in the sixth century, all of whom had also lived and preached in Tamil Nadu, including the Tirunelveli district on the Tamraparni river.[45][46][47] Buddhaghosa expounds in Manorathapurani, his commentary of the Anguttara Nikaya, "tambapannidlpe anurddhapuram majjhimadeso nama" meaning "on Tamraparni island, the city of Anuradhapura serves as the "middle country".[48]

Despite the Mahāvihāra's South Indian connection, the largest and most popular Tamraparniyan Buddhist tradition among the island's indigenous Tamils was the Abhayagiri Vihara sect; an early Brahmi script inscription to the temple's northwest records that the terrace (Pasade) was of the Tamil householders (named Gahapatikana) and was made by Samana, the Tamil Jain from Eelu-Bharata.[50] Pilgrims of the former Jain Giri monastery at the site, built by Pandhukabhaya and later destroyed, continued worship and influence at the Abhayagiri Vihara with the rise of Tamil monks such as Sangamitta Thera. Maha Buddharaksita Sthavira's Rajavamsa-Pustaka, written and preserved at the Abhayagiri Vihara from 277 - 305 CE, means "A Book of Royal Dynasties", which gives an account of Sinhalese occupation of the island, and states that Elara of Anuradhapura, "the son of Maharista, succeeded his father as king of Tamraparni island and Pundra and reigned for forty four years." Early Kings of Anuradhapura such as Mutasiva, Mahasiva and Elara were described as Tamraparni island kings who also ruled the kingdoms of Pundra, Chola and Pandya as dependencies simultaneously. When losing the Pundra and Tamraparni thrones, they sought refuge by sea in Suvarnnapura (Sumatra) in the Malay peninsula, where they died, corroborating the extent of Tamraparniyan power across South East Asia in the classial period.[20][21] Chinese Buddhist monk Faxian of the early 5th century, who used the geography list of the Mahanidessa and Melinda Panha to reach Tamraparni island, describes Abhayagiri Vihara's growth and concurrent existence.[51] In the 7th century CE, Xuanzang also describes the concurrent existence and major divisions of Theravāda in Sri Lanka's monasteries, referring to the Abhayagiri tradition as the "Mahāyāna Sthaviras," and the Mahāvihāra tradition as the "Hīnayāna Sthaviras."[52][53] Vajrabodhi, the celebrated Tantrist Mahayana teacher near Pothigai hills, preached in central and South Sri Lanka, including at Adam's Peak and the Abhayagiri vihara, before journeying to Java, the Malay archipelego and China; he enjoyed the patronage of Siva devotee Narasimhavarman II and many Sri Lankan kings.[54] By the 7th century CE, more rulers of Sri Lanka gave support and patronage to the Abhayagiri Theravādins, and travelers such as Faxian saw the Abhayagiri Theravādins as the main Buddhist tradition in Sri Lanka, before the Tamraparniyan fraternities were forced in unison and the Abhayagiri worship decimated under Parakramabahu I.[55][56]

In the fifteenth century, the monk Chappada from Arimaddana city, Pagan, Myanmar came to the "island of Tambapanni", where, according to the colophon of the Sankhepavannana he authored, he purified the sasana order in Sri Lanka with the help of the king Parakramabahu VI of Kotte whom he was very dear to, in the city of Jayavardhanapura and he "caused a sima to be consecrated, according to the vinaya rules and avoiding all unlawful acts."[57]

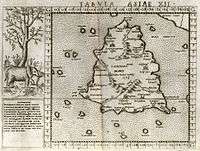

The name "Tamraparni" was adopted into Greek as Taprobana, called as such by Onesicritus and Megasthenes in the 4th century BC.[58] Megasthenes shares in Indica that "Taprobane is separated from the mainland by a river; that the inhabitants are called Palaiogonoi, and that their country is more productive of gold and large pearls than India."[59] Nearchus and Onesicritus, contemporaries of Alexander the Great, mention the island as "Taprobana", which also finds mention in De Mundo of Aristotle and in the world map of another of his students, Dicaearchus. One of the first Geography in which it appears is that of Eratosthenes (276 to 196 BC) and was later adopted by Ptolemy (139 AD) in his geographical treatise to identify Sri Lanka as the relatively large island "Taprobane", south of continental Asia.[60][61][62] Ptolemy names the Pothigai mountain "Bettigo", from where three rivers rise; he uses the term "Solen" for the Tamraparni River in Tirunelveli - the Latin term for chank - in reference to its world-famous pearl fishing.[63][64] "Taprobane" was a new hemisphere according to Hipparchus, Strabo also mentions Taprobane while fellow Roman writer Pliny the Elder states that only during Alexander the Great's rule did the west consider Taprobane to be an island, whose inhabitants worship Hercules and whose King dresses like father Bacchus.[62] Sri Lanka as Taprobane is on the map of Dionysius Periegetes, while it is called "Insula Taprobane" on the Tabula Peutingeriana; the name "Thimara" appears on this Itinerarium, near the most southern river of mainland South India.

The Bengali poet Krishnadasa Kaviraja mentions in Chaitanya Charitamrita the Tamraparni river in Tirunelveli, Pandya Desa, as a holy place Chaitanya Mahaprabhu visited as a pilgrim, and glorifies the Vishnu temple Alwarthirunagari Temple on its bank.[65]

The Greek name was adopted in medieval Irish (Lebor Gabala Erenn) as Deprofane (Recension 2) and Tibra Faine (Recension 3), off the coast of India, supposedly one of the countries where the Milesians / Gaedel, ancestors of today's Irish, had sojourned in their previous migrations.[66][67]

The name remained in use in early modern Europe, alongside the Persianate Serendip, with Traprobana mentioned in the first strophe of the Portuguese national epic poem Os Lusíadas by Luís de Camões. John Milton borrowed this for his epic poem Paradise Lost and Miguel de Cervantes mentions a fantastic Trapobana in Don Quixote.[68]

In epigraphy

A Prakrit inscription at Bodh Gaya in Bihar, on one of the railing bars of the Mahabodhi Temple, details a gift donation to the temple from Bodhirakhitasa, a man from Tamraparni.[69]

Excavations at the Chandraketugarh archaeological site in North India reveal the mast of a ship with Vijayasinha's seal, describing Vijayasinha, the son of the king of Sinhapura of Vanga's marriage to Kuveni – the indigenous Yakkha queen of Tamraparni.[70] Another Brahmi inscriptions with Megalithic Graffiti Symbols from the site read "yojanani setuvandhat arddhasatah dvipa tamraparni", meaning "The island of Tamraparni (now Sri Lanka) is at a distance of 50 yojanas or 50 km from Setuvandha (in Tamil Nadu).[71]

Nagarjunakonda inscriptions of Andhra Pradesh belonging to the Andhra Ikshvaku king Madhariputa Sri Vira Purisadata's reign of 275 CE speak of a convent founding a Chaitya-griha (Chaitya hall) dedicated to the Sthaviravadin (Theravada) teachers, nuns and monk fraternities from Tamraparni island. These Buddhist monks are credited to have converted the people of Kashmir, Gandhara, China, Tosali, Aparanta, Vanga, Vanavasa, Yavana (Greece), Damila, Tamraparna and the isle of Tamraparni at the monastery to their doctrine, a site of great cultural influence and exchange. Vanga Kingdom of Bengal, according to the inscription, was among several regions where "tranquility" (pasada) was brought about by the Sthaviravadin teachers of Tamraparni.[72][73]

Buddhist Bhikkus monks from Tamraparni resided at Navahatta in Bengal in 600 CE.[74] A seal excavated at the site of the Raktamrittika Vihara at Rajbadiganga mentions the community thus Navahatte Tamavanika Bhikshunam meaning "the bhikshus from Tamraparni residing in Navahatta".[75] The language of the inscription is an amalgam of Sanskrit and Prakrit — "Navahatta" is Sanskrit and "Tamavanika" is the Prakritized form of the Sanskrit word "Tamraparnika".[75] It is an identity seal of the monks from Sri Lanka residing at the monastery, part of a votive insignia to the shrine in an offering on behalf of all monks.[74]

A fragmentary slab inscription of Sundara Mahadevi, the queen consort of Vikramabahu I of Polonnaruwa in the 12th century, states that a great Sthaviravadin of the Sinhalese Sangha by the name of Ananda was instrumental in "purifying the order" in Tambarattha.[13]

The 1539 CE engraved inscription of Achyuta Deva Raya, King of the Vijayanagara Empire of Karnataka found in the Rajagopala Perumal Temple of Thanjavur informs that this king conquered Eelam, fought the Battle of Tamraparni, planted a pillar of victory at Tamraparni river following defeat of the Tiruvadi (Travancore) on its banks, and married the daughter of the Pandyan king.[76]

The Nava Tirupathi are a set of nine ancient Hindu temples dedicated to the deity Lord Vishnu, located on the Tiruchendur-Tirunelveli route in Tamil Nadu, all on the banks of the river. Epigraphical references to land next to the Tān-Poruṇdam river and the ownership of this land by respective temples on its banks are frequent from the medieval period. The inscriptions of the Chola temple Tiruvāliśvaram near Tirunelveli, found on the south wall of the mandapa in front of the temple's central shrine, identify the Tamraparni river with its original name Tān-Poruṇdam, describing the use of water from the TānPoruṇdam river to bathe the temple's god on Sundays following a gift.[77] The Mannarkovil inscription of Jatavarman Sundara Chola Pandyadeva relates the sale of land in Tamil Nadu near the river TānPoruṇdam to the Vishnu temple Rajagopalakrishnaswamy Kulasekara Perumal Kovil, in the vicinity of Rajendra Vinnagaram, and the Tirunelveli inscription of King Maravarman Sundara Pandyan II details village zones with TānPoruṇdam river as their boundaries.[78][79]

A Sannyasin repaired and reconsecrated the Tentiruvengadamudaiya Emperuman Shrine between 1398-99 AD at the Pavanasini Tirtha on the TānPoruṇdam river.[80]

References

- 1 2 3 Pillai, M. S. Purnalingam (2010-11-01). Ravana The Great : King of Lanka. Sundeep Prakashan Publishing. ISBN 9788175741898.

- 1 2 3 K. Sivasubramaniam - 2009. Fisheries in Sri Lanka: anthropological and biological aspects, Volume 1. "It is considered most probable that the name was borrowed by the Greeks, from the Tamil 'Tamraparni' for which the Pali...to Ceylon, by the Tamil immigrants from Tinnelvely district through which ran the river called to this date, Tamaravarani"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Leelananda Prematilleka, Sudharshan Seneviatne - 1990: Perspectives in archaeology: "The names Tambapanni and Tamra- parni are in fact the Prakrit and Sanskrit rendering of Tamil Tan porunai"

- 1 2 John R. Marr - 1985 The Eight Anthologies: A Study in Early Tamil Literature. Ettukai. Institute of Asian Studies

- 1 2 3 4 Caldwell, Bishop R. (1881-01-01). History of Tinnevelly. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120601611.

- ↑ The Indian Geographical Journal, Volume 15, 1940 p345

- 1 2 3 Iravatham Mahadevan (2003), EARLY TAMIL EPIGRAPHY, Volume 62. pp. 169

- 1 2 3 Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri (1963) Development of Religion in South India - Page 15

- 1 2 Layne Ross Little (2006) Bowl Full of Sky: Story-making and the Many Lives of the Siddha Bhōgar pp. 28

- ↑ Ameresh Datta. Sahitya Akademi, 1987 - Indic literature. Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: A-Devo. pp 115

- ↑ Mendis, G.C. (2006). "The ancient period". Early History of Ceylon (Reprint ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 386. ISBN 81-206-0209-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mendis, G.C. (2006). "The ancient period". Early History of Ceylon (Reprint ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 33. ISBN 81-206-0209-9. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- 1 2 3 W. M. Sirisena (1978). Sri Lanka and South-East Asia: Political, Religious and Cultural Relations from A.D. C. 1000 to C. 1500 pp. 89

- ↑ Robert Knox. 1651. An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon in the East-Indies. - London. p167

- ↑ Arumugam, Solai; GANDHI, M. SURESH (2010-11-01). Heavy Mineral Distribution in Tamiraparani Estuary and Off Tuticorin. Publishing. ISBN 9783639304534.

- ↑ N. Subrahmanian - 1994. Original sources for the history of Tamilnad: from the beginning to c. A.D. 600

- ↑ Tolkāppiyar, P. S. Subrahmanya Sastri. (1945). Tolkāppiyam-Collatikāram. pp. 30

- ↑ Ajay Mitra Shastri, Varāhamihira (1996). Ancient Indian Heritage, Varahamihira's India: Economy, astrology, fine arts, and literature. Aryan Books International.

- ↑ Govind Sadashiv Ghurye. Caste and Race in India. p357

- 1 2 Kurukshetra, Volume 4. Sri Lak-Indo Study Group, 1978 pp.68-70

- 1 2 Ranjan Chinthaka Mendis. Lakshmi Mendis, 1 Jan 1999. The Story of Anuradhapura: Capital City of Sri Lanka from 377 BC - 1017 Ad pp. 33

- ↑ C. Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. Rasanayagam. (1993). Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portug[u]ese Period. Asian Educational Services. pp. 103-105

- ↑ M. D. Raghavan (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. pp. 60

- ↑ C. Sivaratnam - 1964. An outline of the cultural history and principles of Hinduism. pp. 276

- ↑ Pfaffenberg, Brian (1994). The Sri Lankan Tamils. U.S: Westview Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-8133-8845-7.

- ↑ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. pp. 251

- 1 2 Vyasa. (400 BCE). Mahabharata. Sections LXXXV and LXXXVIII. Book 3. pp. 46-47, 99

- ↑ Romesh Chunder Dutt (2002). The Ramayana and the Mahabharata Condensed Into English Verse. p99

- ↑ V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar. (1995) The Purana Index. pp. 16

- 1 2 Edward Balfour. (1873). Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial, Industrial and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures, Volume 5. Scottish & Adelphi presses. pp. 260

- ↑ M. S. Purnalingam Pillai. Sundeep Prakashan, 1996. Ravana The Great : King of Lanka - Page 84

- 1 2 3 Schalk, Peter. "Robert Caldwell's Derivation īlam<sīhala: A Critical Assessment". In Chevillard, Jean-Luc. South-Indian Horizons: Felicitation Volume for François Gros on the occasion of his 70th birthday. Pondichéry: Institut Français de Pondichéry. pp. 347–364. ISBN 2-85539-630-1..

- ↑ Ramananda Chatterjee - 1930. The Modern Review - Volume 47 - Page 96

- ↑ Ponnambalam Arunachalam, Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam - 2004. Sketches of Ceylon History. pp. 33

- ↑ Bertold Spuler. (1975) Handbook of Oriental Studies, Part 2 pp. 63

- ↑ Anne E. Monius Oxford University Press, 6 Dec 2001. Imagining a Place for Buddhism: Literary Culture and Religious Community in Tamil-Speaking South India. pp. 114

- ↑ G. Kamalakar, M. Veerender, Birla Archaeological & Cultural Research Institute Sharada Pub. House, 1 Jan 2005. Buddhism: art, architecture, literature & philosophy, Volume 1

- ↑ Kisan World, Volume 21. Sakthi Sugars, Limited, 1994. pp. 41

- ↑ Shu Hikosaka (1989). Buddhism in Tamilnadu: A New Perspective - Page 187

- ↑ "Rivers of Western Ghats - Origin of Tamiraparani". Centre for Ecological Sciences. Indian Institute of Science. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Sri Nandan Prasad, Historical Perspectives of Warfare in India: Some Morale and Matériel Determinants, Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture - 2002

- 1 2 Śrīdhara Tripāṭhī. 2008. Encyclopaedia of Pali Literature: The Pali canon - Page 79

- ↑ Debarchana Sarkar Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar, 2003. Geography of ancient India in Buddhist literature. pp. 309

- ↑ Nalinaksha Dutt. Buddhist Sects in India. p 212

- ↑ Es Vaiyāpurip Piḷḷai. Vaiyapuripillai's History of Tamil Language and Literature: From the Beginning to 1000 A.D. New Century Book House, 1988. pp 30

- ↑ A. Aiyappan, P. R. Srinivasan. (1960). Story of Buddhism with Special Reference to South India. pp.55

- ↑ G. John Samuel, Ār. Es Śivagaṇēśamūrti, M. S. Nagarajan - 1998. Buddhism in Tamil Nadu: Collected Papers - Page xiii

- ↑ Anne E. Monius, Oxford University Press, 6 Dec 2001. Imagining a Place for Buddhism: Literary Culture and Religious Community in Tamil-Speaking South India. pp 106

- ↑ Upendra Thakur (1986). Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture. pp. 42

- ↑ Ruth Barnes, David Parkin. (2015) Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology on the Indian Ocean. pp. 101

- ↑ "Chapter XXXVIII: At Ceylon. Rise of the Kingdom. Feats of Buddha. Topes and Monasteries. Statue of Buddha in Jade. Bo Tree. Festival of Buddha's Tooth.". A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ Baruah, Bibhuti. Buddhist Sects and Sectarianism. 2008. p. 53

- ↑ Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. 2007. p. 121

- ↑ Nandana Cūṭivoṅgs, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. (2002). The iconography of Avalokiteśvara in Mainland South East Asia. pp5

- ↑ Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. 2007. p. 125

- ↑ Sujato, Bhikkhu. Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools. 2006. p. 59

- ↑ Buddhadatta, UCR, Vol. IX, p.74

- ↑ Friedman, John Block; Figg, Kristen Mossler (2013-07-04). Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135590949.

- ↑ Jyotirmay Sen. "Asoka's mission to Ceylon and some connected problems". The Indian Historical Quarterly. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ↑ W. J. Van Der Meulen, Suvarnadvipa and the Chryse Chersonesos, Indonesia, Vol. 18, 1974, page 6.

- ↑ Suárez, Thomas. Early Mapping of Southeast Asia. Periplus Editions. p. 100. ISBN 962-593-470-7.

- 1 2 Asian Educational Services (1994). A General Description of the Island, Historical, Physical, Statistical pp. 14-16

- ↑ Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya - 1980. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea & Ptolemy on Ancient Geography of India

- ↑ Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, 1994. PILC Journal of Dravidic Studies: PJDS., Volume 4

- ↑ Ontological and Morphological Concepts of Lord Sri Chaitanya and His Mission, Volume 1. Bhakti Prajnan Yati Maharaj, Chaitanya, Bhakti Vilās Tīrtha Goswāmi Maharāj Sree Gaudiya Math, 1994. pp. 248

- ↑ Lebor Gabala Erenn Vol. II (Macalister translation)

- ↑ In the early 1800s, Welsh pseudohistorian Iolo Morganwg published what he claimed was mediaeval Welsh epic material, describing how Hu Gadarn had led the ancestors of the Welsh in a migration to Britain from Taprobane or "Deffrobani", aka "Summerland", said in his text to be situated "where Constantinople now is." However, this work is now considered to have been a forgery produced by Iolo Morganwg himself.

- ↑ Don Quixote, Volume I, Chapter 18: the mighty emperor Alifanfaron, lord of the great isle of Trapobana.

- ↑ Hari Kishore Prasad - 1970. The Political & Socio-religious Condition of Bihar, 185 B.C. to 319 A.D. pp.230

- ↑ Sambhu Nath Mondal. 2006. Decipherment of the Indus-Brâhmî Inscriptions of Chandraketugarh (Gangâhrada)--the Mohenjodaro of East India. pp28 vijayasihasa bivaha sihaurata tambapaniah yakkhini kubanna,a" Sanskritized as "vijayasirihasya vivaha sirihapuratah tamraparnyah yaksinf kubarjuaaya"

- ↑ Sambhu Nath Mondal. 2006. Decipherment of the Indus-Brâhmî Inscriptions of Chandraketugarh (Gangâhrada)--the Mohenjodaro of East India. pp28 Sanskritization : "yojanani setuvandhat arddhasatah dvipa tamraparni"

- ↑ The Maha Bodhi (1983) - Volume 91 - Page 16

- ↑ Sakti Kali Basu (2004). Development of Iconography in Pre-Gupta Vaṅga - Page 31

- 1 2 Parmanand Gupta (1989). Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals. p183

- 1 2 Indian History Congress. 1973. Proceedings - Indian History Congress - Volume 1 - Page 46.

- ↑ C. Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. Rasanayagam. (1993) Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portuguese Period. pp385

- ↑ K. D. Swaminathan, CBH Publications, 1990 - Architecture. South Indian temple architecture: study of Tiruvāliśvaram inscriptions. pp. 67-68

- ↑ Epigraphia Indica - Volume 24 - Page 171 (1984)

- ↑ Niharranjan Ray, Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya - 2000. A Sourcebook of Indian Civilization - Page 484

- ↑ R. Tirumalai, Tamil Nadu (India). Dept. of Archaeology (2003). The Pandyan Townships: The Pandyan townships, their organisation and functioning