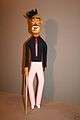

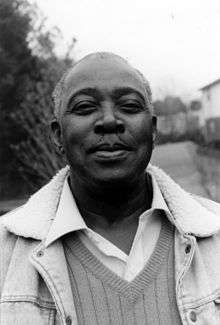

Sulton Rogers

Sulton Rogers (1922 – April 5, 2003) was a Mississippi folk artist who spent most of his life in Syracuse, New York working at a chemical plant. He moved back to Oxford, Mississippi in 1995 and lived there until he died.

Rogers referred to his carvings as "haints" and primarily carved humans with oversized features. The oversized features included multiple eyes, animals coming out of body parts, and extra breasts.[1] He would also carve multiple related carvings known as "haint houses".[2] These pieces sometimes included dollhouses that would be filled with the human carvings. While he normally carved people, he would also carve animals.

“Yeah, my dad sorta taught me how to carve. He used to have a big laugh at me ‘cuz I might make a dog and I’d be carving his head or something. Maybe I’d cut his ear off, through a mistake or something. He’d laugh at me. So I’d throw it away, got to start all over again. He’d say, ‘Now you think you can’t put on, but you can take off. If you take off, you can’t put it back on.’Then, when I got older and went to work at the chemical plant, they all knowed what I was doing. I was doing that ‘cuz I never would go to sleep. I’d be carving to keep me awake or something like that. Well, that’s when I really went back to carving. I always did have something I like to put on wood. I actually saw a piece of wood that kinda reminded me of something, and so I started carving. I used to make pieces and set them in the window. You’d go to lunch, you’d come back and it’d be gone. And so I fixed them. I made a coffin with a dead man and stuck it in the window. He stayed there for about 2 months and nobody bothered it. We had a lot of fun with that thing. Nobody bothered. It’d sit there in the window and look at them, and nobody looked at it. Nobody steal nothing. If it was anything else, they’d get it. So maybe they thought it was like a booby trap.

So when I retired from Allied Chemical, they bought me a pocket knife. They bought me some sandpaper and some wood like I usually bought then. They bought me that stuff and it had lines on each one of them. It said, ‘Now you do your carving on your own time, not the company’s time.’

Now some people don’t know what to make of my carving. I got a couple of friends that come to the house, they don’t go to the cellar ‘cuz I usually have coffins sitting around there. You know the fellow I rent from, he don’t go down there. He says if anything would break, you fix it because I ain’t going down there. Then if he does come, he says if you gonna make things then cover them up so I can’t see ‘em, put a sheet or something on ‘em. One night he come to the door and I was trying to put a wig on those dead people in the coffin. He told me I was an idiot for doing stuff like that.

I was down there one night. I was working, and you get to thinkin’ about what people tell you. I decided I’d get out of there. I felt good leaving out of there. But, most of the time, like sometime where I don’t get sleep or come in late, I go in there at 12 o’clock and work up until three. I don’t get sleepy. I just be thinking all kind of stuff.

I just try to make the best of my life. I try to make things good enough as best I can to stay out of worry. Sometimes I get up, something I making and I can’t figure it out. And that bothers me. That’s where I go out. My mind’s stuck on it. Like somebody’s arm or nose don’t come out so well. I’m gonna think about it and finish this. I’ll do it, too. Any time I get something I can’t handle, it bothers me. I’ll leave and go get me a sandwich and coffee, and around a little bit I’ll get that off my mind, and I think about it and come back and do it. When you go back, you have a different idea and you’re gonna do it. ‘Cuz mainly it just stays stuck on my mind ‘til it get done.”

– Sulton Rogers, 1991 (Artist’s Alliance- It’ll Come True).

His pieces are the part of permanent collections at the University of Mississippi Museum of Art, the African American Museum, and the University Art Museum. His carvings have also appeared in the Dallas Museum of Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, and the American Visionary Art Museum.[3] Collectors should be aware that auction houses and some publications misspell his name as "Sultan Rodgers".

Family life

Rogers was married in 1941 at age 19 and had a son named Van. He later married Ardeula in 1945 and they conceived seven children together, RV, Allie B., Willie Sulton, Eddie, Sammie, Lossie, and Loretta. He also fathered Bobby, Roy, Jackie, Katie, and Jimmy. Although he left his family in Mississippi to seek employment in New York, he reunited with his family many years before his death.[4]

References

- ↑ "GMOA exhibitions in the news". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "Sulton Rogers". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "Sulton Rogers". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ "Robert Cargo Folk Art Gallery". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Delahanty, Randolph, Art in the American South

- Artist's Alliance, It'll Come True

External links

- Mississippi Museum of Art

- American Visionary Art Museum

- University Art Museum

- Dallas Museum of Art

- New Orleans Museum of Art

- African American Museum

- Folk Art

- Gordon Gallery

- Rising Fawn Folk Art