Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering

Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering (SPICE) was a United Kingdom government-funded climate engineering (geoengineering) research project that aimed to assess the feasibility of injecting particles into the stratosphere from a tethered balloon for the purposes of solar radiation management.

Overview

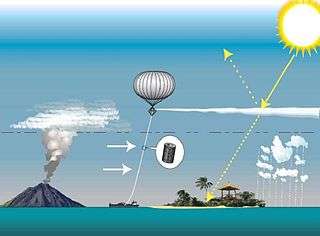

The project investigated the feasibility of one geoengineering[1] technique: solar radiation management using stratospheric sulfur aerosols. This could produce the same type of global cooling effect as a large volcanic eruption – such as Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in June 1991 (but without any disruption from hot lava, ash or smoke, which would not be present). In the two years following that eruption the Earth cooled on average by about half a degree Celsius.[2][3]

The SPICE project investigated whether or not these natural processes can be mimicked and, if so, with what effect. It was one of the first UK projects aimed at providing evidence-based knowledge about geoengineering technologies. The project itself did not carrying out geoengineering, but it investigated the feasibility of doing so. SPICE sought to shed light on some of the uncertainties surrounding this controversial subject, and encourage debate to help inform any future research and decision-making. Geoengineering is seen as being potentially useful in combating climate change but could also lead to unforeseen or unintended risks – for example on local weather systems, or discouraging people to take action to reduce carbon emissions.

The project was funded by a £1.6m grant by the EPSRC to run from October 2010 to March 2014.[4]

Project status

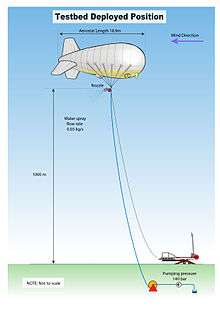

In October 2011 a planned outdoor test (named 1km testbed at a 1/20 scale) was delayed for six months, as a result of controversy surrounding the research. The project oversight panel decided that more public engagement and better transparency was needed.

In May 2012 the first field test was cancelled altogether in agreement of all project partners.[5] Dr. Matthew Watson, the project´s lead scientist, named two reasons for the cancellation: First, project scientists had submitted patents for similar technology, presenting a potentially significant conflict of interest. In addition to that, concerns about the lack of government regulation of such geoengineering projects were raised.[6]

Although the field testing was cancelled, the project panel decided to continue the lab-based elements of the project.[7]

Work packages

The SPICE project consisted of three strands of research (Work Packages):

Evaluating candidate particles

Researchers from the Universities of Bristol, Oxford and Cambridge and the Rutherford-Appleton Laboratory considered what would be an ‘ideal’ particle to inject into the stratosphere. The researchers aimed to identify a particle with excellent solar radiation scattering properties, and consider what potential impacts might be on climate, weather, ecosystems and human health.

Delivery systems

Engineers from the University of Cambridge and Marshall Aerospace planned to assess the effect of wind on a tethered ballon at a height of 1 km while at the same time pumping water at a rate of around 100 kg/hour.[8] They hoped to use the data obtained from these tests in computer models aimed at examining how a full-scale tethered balloon might behave in the high winds experienced at altitudes up 20 km.

Climate and environmental modelling

Researchers from the Universities of Oxford, Edinburgh and Bristol worked with the Met Office's Hadley Centre to consider what can be learned from past volcanic eruptions. They also modelled the potential impact on ozone layer concentrations, regional precipitation changes and atmospheric chemistry.

Public engagement

A consultation exercise was undertaken with members of the public in a parallel project by Cardiff University, with specific exploration of attitudes to the SPICE test.[9] This research found that almost all participants were willing to allow the field trial to proceed, but very few were comfortable with the actual use of stratospheric aerosols.

The project was presented to the public at the British Science Festival in Bradford, 13 September 2011 to coincide with plans to conduct the 1 km delivery system testbed in Norfolk the following month.[10] However, this was later postponed for six months[11] following advice from a Phase–gate model advisory panel to "allow more time for engagement with stakeholders".[12]

Following the original announcement, a campaign opposing geoengineering led by the ETC Group drafted an open letter calling for the project to be suspended until international agreement is reached,[11] specifically pointing to the upcoming convention of parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2012.[13]

Research

Early research so far includes showing that many state of the art climate models do not successfully simulate the atmospheric circulation changes following large volcanic eruptions, which is "of concern for the accuracy of geoengineering modeling studies that assess the atmospheric response to stratosphere-injected particles.", led by Simon Driscoll,[14] the detailing of radiative properties of possible candidate particles, led by Francis Pope,[15] and assessments of costs and lead times for technological development of various lifting options for stratospheric aerosols, led by Peter Davidson.[16] Research led by Jim Haywood supported by the SPICE programme shows "large asymmetric stratospheric aerosol loadings concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere are a harbinger of Sahelian drought whereas those concentrated in the Southern Hemisphere induce a greening of the Sahel." which is particularly of concern for the impacts of geoengineering because "The Sahelian drought of the 1970s–1990s was one of the largest humanitarian disasters of the past 50 years, causing up to 250,000 deaths and creating 10 million refugees.". [17]

SPICE member Simon Driscoll has expressed caution about sulphate aerosol geoengineering given that we do not yet know the full effects and that there may be adverse effects from unintended consequences of sulphate aerosol geoengineering.[18][19][20]

References

- ↑ "Geoengineering the climate: science, governance and uncertainty". The Royal Society. 1 Sep 2009.

- ↑ "Scientists to create artificial volcano for climate change experiment". Daily Telegraph. 14 Sep 2011.

- ↑ "Trial aims to hose down warming climate". The Financial Times. 14 September 2011.

- ↑ EPSRC (19 November 2010). "SPICE: Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering". The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council EPSRC.

- ↑ Michael Marshall (22 May 2012). "Controversial geoengineering field test cancelled". New scientist. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Dr. Mathew Watson (blog) (16 May 2012). "Testbed News". Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Erin Hale (16 May 2012). "Controversial geoengineering field test cancelled". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Phil McKenna (14 September 2011). "British to Test Geoengineering Scheme". The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ↑ Nick Pidgeon, Karen Parkhill, Adam Corner and Naomi Vaughan (14 April 2013). "Deliberating stratospheric aerosols for climate geoengineering and the SPICE project". Nature Climate Change.

- ↑ "SPICE project announced at British Science Festival". Bristol University. 14 Sep 2011.

- 1 2 Michael Marshall (3 October 2011). "Political backlash to geoengineering begins". New Scientist.

- ↑ "Update on the SPICE project". EPSRC. 29 Sep 2011.

- ↑ "Open letter about SPICE geoengineering test". ETC Group. 27 Sep 2011.

- ↑ "Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) simulations of climate following volcanic eruptions". Journal of Geophysical Research. 6 Sep 2012.

- ↑ "Stratospheric aerosol particles and solar-radiation management". Nature Climate Change. 12 August 2012.

- ↑ "Lifting options for stratospheric aerosol geoengineering: Advantages of tethered balloon systems". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 13 September 2012.

- ↑ "Asymmetric forcing from stratospheric aerosols impacts Sahelian rainfall". Nature Climate Change. 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "Can Humans Survive?". The Daily Beast. 6 May 2013.

- ↑ Newtiz, Annalee (14 May 2013). "Interviewed in "Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction"". Doubleday.

- ↑ "Interviewed in "Bij God in Oxford: reddingsplannen voor de klimaatverandering" by Filip Rogiers". De Standaard. 24 May 2013.