Staballoy

Staballoy is the name of two different classes of metal alloys, one class typically used for munitions and a different class developed for drilling rods.

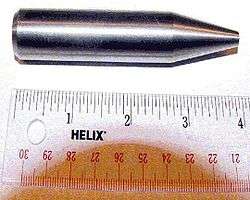

In a military context, staballoys are metal alloys of a high proportion of depleted uranium with other metals, usually titanium or molybdenum, designed for use in kinetic energy penetrator armor-piercing munitions. One formulation has a composition of 99.25% of depleted uranium and 0.75% of titanium. Other variants can have 3.5% of titanium. They are about 70% more dense than lead.

An alternative to staballoys in kinetic penetrator munition is tungsten, but it is more expensive, more difficult to machine and is not pyrophoric, so the munition lacks the incendiary effect enhancing its impact. Tungsten penetrators also tend to form mushroom shaped tip during armor penetration, while uranium ones tend to be self-sharpening.[1]

An emerging alternative alloy of depleted uranium is stakalloy, formed of niobium (0.01-0.95 wt.%), vanadium (1-4.5 wt.%, between gamma-eutectoid and eutectic) and uranium (balance). It has improved machinability. It can be also used in structural applications.[2]

Staballoy is also a name for a class of commercially used stainless steels used for drilling rods for drilling rigs. An example is Staballoy AG17 which is a different material from military staballoy, and contains 20.00% manganese, 17.00% chromium, 0.30% silicon, 0.03% carbon, 0.50% nitrogen, and 0.05% molybdenum, alloyed with iron. It is nonmagnetic.

References

- Trueman E. R.; Black S.; Read D. (2004). "Characterisation of depleted uranium (DU) from an unfired CHARM-3 penetrator". Science of the Total Environment. 327 (1–3): 337–340. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00401-7. PMID 15172592.

- Pollanen R.; Ikaheimonen T. K.; Klemola S.; Vartti V. P.; Vesterbacka K.; Ristonmaa S.; Honkamaa T.; Sipila P.; Jokelainen I.; Kosunen A.; Zilliacus R.; Kettunen M.; Hokkanen M. (2003). "Characterisation of projectiles composed of depleted uranium" (PDF). Review of tungsten-based kinetic energy penetrator materials. 2–3: 133–142.