Socialism in New Zealand

The degree to which socialism in New Zealand has been of significance in mainstream politics is debated, as varying definitions of socialism and communism make the extent of its influence difficult to measure. New Zealand has a complicated assortment of socialist causes and organizations. Some of these play a considerable role in public activism - some commentators claim that New Zealand socialists are more prominent in things such as the anti-war movement than in promoting actual socialism itself. Other groups are strongly committed to radical socialist revolution.

Present status of New Zealand socialism

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of New Zealand |

| Constitution |

|

|

|

|

Related topics |

The extent to which socialism plays a part in modern New Zealand politics depends on which definitions of socialist are used, but few mainstream politicians would describe themselves using the word "socialist". The term "social democrat" is more common, but the more general "left-wing" or "centre-left" are used far more frequently.

Nevertheless, socialists of various types are still to be found in modern New Zealand politics. The Labour Party and the former Progressive Party all have some links to socialism in their history, but under a New Zealand definition, they would generally not be considered socialist today. More likely to receive this label are the small socialist or communist organisations that exist outside the mainstream political world - examples include Fightback, the International Socialist Organisation and Socialist Aotearoa.

History of New Zealand socialism

Milburn argues that socialist theories were introduced by immigrant workers with experience in the British labour movement. Their ideas were not widely accepted, however. The Liberal government that was dominant 1891-1912 rejected socialism but it supported unions and the Liberal Government of New Zealand set up the country's welfare state in the 1890s and fought the large land holders. She argues that governmental activism cannot be attributed to the influence of the small socialist movement.[1]

Non-ideological socialism

The growth of socialism as an ideology in New Zealand only began to occur around the beginning of the 20th century. Some historians, however, claim that a sort of "non-ideological" socialism was born shortly after the establishment of self-government, and flourished in the late 19th century. This, they say, was mostly in the form of a "paternalistic" government which believed in the need to speed the country's economic growth, rather than in the form of an ideologically leftist government. These historians argue that because of New Zealand's small size and its focus on agriculture, the newly established government was forced to assume responsibility for many things that would otherwise be undertaken by private enterprise - railways, banking, insurance, and many other things that New Zealand's small business sector could not yet afford. Premier Julius Vogel was a notable advocate of government projects of this nature. Later, the Liberal Party was accused by its opponents of being "socialist", although most within the party rejected this. One commentator has claimed that until the Russian Revolution of 1917, New Zealand was the most socialist country in the world, although many believe that this is overstating the case. 🇳🇿

Workers' parties

Ideological socialism, when it arrived, mostly stemmed from Britain or other British colonies. Much of socialism's early growth was found in the labour movement, and often coincided with the growth of trade unions. The New Zealand Federation of Labour was influenced by socialist theories, as were many other labour organizations.

In 1901, the New Zealand Socialist Party was founded, promoting the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The group, despite being relatively moderate when compared with many other socialists, met with little tangiable success, but it nevertheless had considerable impact on the development of New Zealand socialism. In particular, Edward Hunter (sometimes known under the pen name "Billy Banjo", and a member of both the Socialist Party and the Federation of Labour), was a major figure in the spread of socialist ideas to the unions.

The growth of unionism eventually led to the establishment of a number of socialist-influenced parties. Originally, the working class vote was concentrated mainly with the Liberal Party, where a number of prominent left-wing politicians (such as Frederick Pirani) emerged. Later, however, there were increasing calls for an independent workers' party, particularly as the Liberals began to lose their reformist drive.

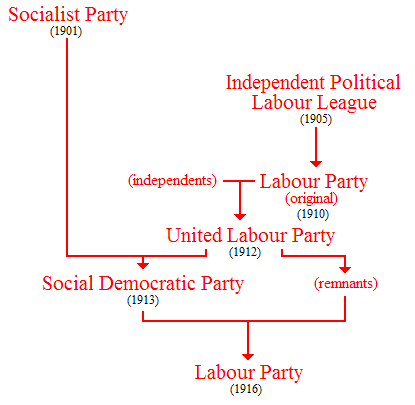

The second organised party to gain a seat in Parliament (after the Liberal Party) was the small Independent Political Labour League, which won an urban electorate in Wellington in the 1908 elections. Later, in 1910, the IPLL was reformed as the Labour Party (not to be confused with the modern party).

Unification of the labour movement

The growing drive for unity among left-wing groups resulted in a "Unity Conference" being called in 1912. This conference aimed to merge the various left-wing parties in New Zealand, including both the moderate Labour Party and the hardline Socialist Party. The Socialist Party, however, refused to attend the conference, and the new United Labour Party consisted only of the Labour Party and a number of independent campaigners.

Premier William Massey's "heavy-handed" suppression of the Waihi miners' strike prompted another attempt at unity in 1913. This time, the Socialists were willing to attend. A new group, the Social Democratic Party, was formed, merging the United Labour Party and the Socialist Party. A faction of the United Labour Party refused to accept the decision, however, and continued on under the same name. Later, a decision by the Social Democrats to support a strike of dockworkers and coal miners resulted in a number of Social Democratic leaders being arrested, leaving the party in disarray – in the 1914 elections, the remnants of the United Labour Party actually won more seats than the "united" Social Democrats.

Finally, in 1916, it was agreed that the Social Democrats and the United Labour Party remnants would all be amalgamated into a single group, the New Zealand Labour Party. The new Labour Party was explicitly socialist, and was based around goals of redistribution of wealth, nationalization of industry, and elimination of conscription. Eventual Labour Party leader, Harry Holland, was strongly socialist in his beliefs, having been associated with the Socialist Party and with the striking miners in Waihi. Holland believed that the militancy at Waihi was a sign of impending class warfare. While the Labour Party gained some electoral success, it continued to trail the Liberal Party and the Reform Party until the replacement of Holland with Michael Joseph Savage. Savage, although also involved in the earlier Socialist Party, was more moderate than Holland, and Labour gained considerable support. Assisted by the Great Depression, Labour won a decisive victory in the 1935 elections.

The early socialism of the Labour Party gradually faded, however. Two years after the Labour Party lost the 1949 elections, the goal of implementing "the socialisation of the means of production, distribution, and exchange" was removed from the party's policy platform. This is sometimes seen as the end of any real claim to full socialism by the Labour Party. The shift away from socialism had not come about without dispute, however – Labour Party politician John A. Lee was harshly critical of the changes, and had eventually left to establish the Democratic Labour Party in 1940. The party was considerably more socialist than Labour, but performed poorly. Many members eventually left the party, mostly due to Lee's perceived autocratic style.

Reassertion of communism

Even before Holland's replacement, and especially after Labour's 1949 policy change, many people had come to the conclusion that the Labour Party had moved too far away from its socialist roots. Only two years after Labour's foundation, the New Zealand Marxian Association was established. It would later clash acrimoniously with Holland. The Marxian Association itself would fall prey to internal division – in 1921, a number of members who supported the Russian Revolution departed to form the Communist Party of New Zealand. The remaining Marxians, who denied that the Russian Revolution represented genuine socialism, gradually declined in influence, and the Association collapsed in 1922.

In 1930, however, former members of the Marxian Association (backed by members of the Socialist Party of Australia) established the Socialist Party of New Zealand (distinct from the earlier New Zealand Socialist Party). This group denied that the Labour Party (or even any of the parties before it, except for the Marxian Association) represented genuine socialism. The new Socialist Party still exists today, although has slightly modified its name (becoming the World Socialist Party of New Zealand).

The Communist Party, meanwhile, was active in attempting to gain support in the unions. The Auckland region's Trade Council was a significant bastion for the party in the 1940s. The party faithfully followed the official position of the Soviet Union, and therefore adopted Stalinism - this was criticised by the Socialist Party, which claimed that Stalinism was not socialism at all.

When the Sino-Soviet split occurred in the 1960s, the Communist Party was sharply divided between supporters of the Soviet Union (led by the "revisionist" Nikita Khrushchev) and supporters of China (led by the radical Mao Zedong). Eventually, the Maoists triumphed, and supporters of Khrushchev were expelled. The expelled members eventually established the Socialist Unity Party, although there is debate how that group should properly be classified. The Socialist Unity party eventually suffererd its own split, with some members departing to found the modern Socialist Party of Aotearoa.

In 1969, a group called the Socialist Action League (now the Communist League) was established. The League has proven to be one of the more durable parties, and contested two seats in the 2002 elections. Numerous other parties have been established since then, but few have proven as stable.

After Mao's death, the Communist Party rejected the reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping. Instead, they followed Albania, which was led by Enver Hoxha. The leadership of the party believed that Hoxha was the only communist leader to keep "real" communism, but the group's determination to follow the narrowest path available alienated many of its supporters. The party gradually declined. After the collapse of Albanian communism, the party adopted the Trotskyism it had once harshly condemned, and merged with a newer group known as the International Socialist Organization. The resultant party was called the Socialist Workers Organization. Later, however, many supporters of the International Socialist Organization withdrew from the new party, reestablishing their old group. As such, some see the Socialist Workers Organization (SWO) as a continuation of the old Communist Party. The SWO, known then as Socialist Worker, voted to dissolve itself in January 2012.

Other groups continue to promote socialism as well. In the 2002 elections, four candidates were put forward an umbrella group (known as the Anti-Capitalist Alliance) consisting of the Workers Party of New Zealand, the Revolution group, and other left-wing activists. The International Socialist Organization is also active at some universities.

Socialist parties in New Zealand

There are around twenty political parties or organizations in New Zealand which follow socialist or communist policies. It is often difficult to gain a clear picture of socialist parties in New Zealand - mergers, splits, and renamings leave the situation confused. In 2013, only Socialist Aotearoa, Fightback and the International Socialist Organisation held regular public meetings and maintained regularly updated websites.

Modern parties and organizations

- Aotearoa Workers Solidarity Movement

- Beyond Resistance

- Communist League - a Trotskyist group established in 1969 as the "Socialist Action League". It has links to the Socialist Workers Party of the USA. The Communist League had two candidates in the 2002 elections, but neither won their respective races. The League also stood candidates in the 2010 Auckland council election.

- Communist Workers' Group - a Trotskyist group. It was established in 1995 as a splinter group from the Workers' Power organization. It is associated with the global Liaison Committee of Militants for a Revolutionary Communist International alliance, which itself was a split from the gobal alliance that Workers' Power belonged to. Their website is redrave.blogspot.co.nz.

- Fightback - formerly the Workers Party, which was previously the Anti-Capitalist Alliance. Branches in Wellington and Auckland and a monthly publication. Some members have worked as organisers for Unite Union. Fightback publishes a monthly magazine by the same name.

- International Socialist Organization - a revolutionary Trotskyist group that is particularly active in universities. It briefly attempted to merge with the remnants of the Communist Party of New Zealand, forming the Socialist Workers Organization. However, the majority of the group eventually rejected this decision and reestablished their own party but were now outside of the International Socialist Tendency. The ISO has fraternal relations with Socialist Alternative, in Australia, and the International Socialist Organisation, USA. Branches in Auckland, Wellington and Dunedin. Bi-monthly magazine called Socialist Review.

- Permanent Revolution Group - a Trotskyist group established as a breakaway from the Spartacist League (which later became the Workers' Power organization). It is associated with the International Bolshevik Tendency.

- Socialist Aotearoa - an Auckland-based group formed in May 2008 which split from Socialist Worker (Aotearoa) over disagreement with the organization's participation in the Residents Action Movement electoral coalition. The group has an eclectic mix of Trotskyists, anarchists, ecosocialists and various other ideologies in its ranks. Members are active in Unite Union, with one member, Joe Carolan, a senior organiser in that union.

- Socialist Voice - a Trotskyist group established in 2002. It is associated with the Committee for a Workers' International, and is therefore linked to the Socialist Party of England and Wales.

- Socialist Party of Aotearoa - a Marxist-Leninist group. It was founded in 1990 as a split from the Socialist Unity Party, which was itself a split from the Communist Party of New Zealand.

Defunct parties and organizations

- New Zealand Socialist Party (1901-1913) - an organization established in 1901. It should not be confused with the Socialist Party of New Zealand, a completely separate organization which is now known as the World Socialist Party of New Zealand.

- Communist Party of New Zealand (1921-1994) - an old communist group that initially gained a modest measure of success, but which later declined. The party became attached to Stalinism, and when the Sino-Soviet split occurred, the party adopted Maoism. Later, after Mao's death, it followed Enver Hoxha, leader of Albania (which they considered to be the last bastion of true communism). After the fall of Albania, the party renounced all these ideologies and adopted Trotskyism. The party then attempted a merger with the International Socialist Organization, creating the Socialist Workers Organization. Most of the International Socialists eventually withdrew from this coalition, leaving the new Socialist Workers Organization dominated by the former Communist Party.

- World Socialist Party of New Zealand (1930-??) - a group based primarily around opposition to Leninism. It was originally established in 1930 simply as the "Socialist Party of New Zealand", but later added "world" to its name. It is affiliated with the World Socialist Movement.

- Socialist Unity Party (1966-1990) - a pro-Soviet party established by expelled members of the Communist Party. The Communist Party had been split between supporters of the Soviet Union and supporters of Mao Zedong's China, and the pro-Soviet faction eventually lost. The Socialist Unity party survived until relatively recently, and maintained a relatively high level of influence in the trade union movement.

- Socialist Worker (Aotearoa) (?-2012). A revolutionary socialist group aligned with the International Socialist Tendency. Formerly known as the Socialist Workers Organisation, the final conference of SW voted to dissolve itself at its conference in January 2012.

- Workers Party of New Zealand (2002-2013) - The party was founded in 2002. It was originally formed by an electoral alliance of the original Workers' Party (pro-Mao, Marxist-Leninist) and the pro-Trotsky Revolution group. it is the first, and so far only, registered hard left political party under mixed-member proportional (MMP) representation.

- Black Cat BlackCat Anarchist Collective - an anarcho-communist group based in the city of Auckland.

- Communist Party of Aotearoa - a Maoist group that split from the Communist Party of New Zealand in 1993, condemning that organization's abandonment of Maoism and adoption of Trotskyism.

- Revolutionary Communist League of New Zealand founded in 1984 by students and lecturers at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch. It was a revolutionary Marxist group affiliated with the United Secretariat of the Fourth International. After a few conferences, intending to rally opposition to Rogernomics, RCLNZ organized a larger nationwide grouping called Socialist Alliance which stood a candidate in the 1987 general election. The RCLNZ was transformed into the Socialist Workers' Project in 1990, based in the ChCh Centre for Socialist Education.

- New Zealand Marxian Association - a group established in 1918. It was founded to give endorsement and support to "Marxian Revolutionist" candidates in general elections.

- Organisation for Marxist Unity - a Maoist group.

- Revolutionary Workers League - a merger of the pro-Mao, Marxist-Leninist Workers' Party of New Zealand and the Revolution group. A tendency within the modern Workers' Party of New Zealand.

- Socialist Workers Organization - a revolutionary Trotskyist party. It was established by the Communist Party of New Zealand and the International Socialist Organization, although the majority of the latter group eventually withdrew from the merger. It was linked to the International Socialist Tendency. It evolved into the present day Socialist Worker (Aotearoa) group.

- Workers' Party of New Zealand (pro-Mao, Marxist-Leninist) - A pro-Mao, Marxist-Leninist party founded by Ray Nunes, formerly a prominent member of the Communist Party of New Zealand. The party joined the Anti-Capitalist Alliance (ACA), a radical-left electoral alliance, in 2002. The Workers' Party merged with Revolution to become the Revolutionary Workers' League in 2004.

- Workers' Power - a Trotskyist group formed in 1981 with links to the global Workers' Power entity. It later absorbed a group called the "Communist Left". It is linked to the League for a Fifth International.

Prominent figures in New Zealand socialism

- Edward Hunter (aka "Billy Banjo")

- John A. Lee

References

- ↑ Josephine F. Milburn, "Socialism and Social Reform in Nineteenth-Century New Zealand," Political Science (1960) 12#1 pp 62-70

Further reading

- Olssen, Erik. "W. T. Mills, E. J. B. Allen, J. A. Lee, and Socialism in New Zealand," New Zealand Journal of History (1976) 10#2 pp 112–129.

- Milburn, Josephine F. "Socialism and Social Reform in Nineteenth-Century New Zealand," Political Science (1960) 12#1 pp 62–70

External links

- Leftist Parties of New Zealand - contains links and statistics for left-wing (not necessarily socialist/communist) parties in New Zealand. Includes links to most parties mentioned above.