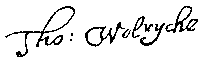

Sir Thomas Wolryche, 1st Baronet

Sir Thomas Wolryche, 1st Baronet (1598–1668) was an English landowner and politician who sat in the House of Commons for Wenlock between 1621 and 1625. He fought in the Royalist army in the English Civil War, serving as military governor of Bridgnorth.

Background and early life

Wolryche was born at Worfield,[1] the son of:

- Francis Wolryche of Dudmaston, Shropshire. The Wolryches had large estates in Shropshire, centred on Dudmaston, on the River Severn to the south of Bridgnorth, which they had acquired from the de Dudmaston family through marriage in the early 15th century.[2]

- Margaret Bromley, daughter of George Bromley of Hallon,[3] an estate to the south and east of Worfield. The Bromleys were a dynasty of lawyer-politicians with many branches and great influence in the Welsh marches. Margaret Bromley's uncle, Thomas Bromley, had risen to become Lord Chancellor.

Thomas Wolryche was born in the home of another Thomas Bromley, his mother's nephew, as Sir George and his eldest son, Francis Bromley, had died some years earlier. One of his godfathers was Margaret Bromley's brother, Edward Bromley,[4] a prominent member of the Inner Temple and later a Baron of the Exchequer.[5] He succeeded his father in 1614.[1] As he was still a minor, he was subject to wardship, a potentially costly period in which his estates might profit a stranger. He was rescued from this as, at the age of 16, his wardship was purchased by his mother and uncle, Sir Edward Bromley[2]

Family tree

Education

Wolryche matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge at Easter 1614.[6] Edward Bromley then secured him a special admission to the Inner Temple, ratified by the Inn's parliament on 15 October 1615, along with his relative Philip Bromley, the youngest son of Henry Bromley.[7] Edward Bromley was intending to adopt Philip as heir to his personal property. Wolryche was to be his political protegé for some years.

Landowner

Francis Wolryche had considerable debts. His will appointed as trustees Edward Bromley and Roger Puleston, husband of Thomas's aunt, if necessary until Thomas reached 30 years of age.[2]

Dudmaston, Wolryche's seat, was the centre of an 800-acre estate. Altogether the Wolryche estates covered about 4,500 acres, mainly in southern and eastern Shropshire, including the manor of Wroxeter to the east of Shrewsbury. In 1611, Thomas Wolryche's father, Francis, had taken over the mortgage of his indebted, recusant brother-in-law, William Gatacre, on the manor of Hughley, about 6 km from Much Wenlock,[8] guaranteeing his debts to the sum of £1,740.[2] This was the most awkward of the financial issues Wolryche faced and it was cleared in 1623 by paying the debt in return for the freehold of Hughley, an estate of 1,400 acres.

Parliamentary career

Bromley was recorder of Much Wenlock, a small town built on the wool trade which was in decline in this period.[9] The borough or liberty of Wenlock was identified with the whole parish of Holy Trinity church in the town by its charter of 1468.[10] When Wenlock Priory was dissolved, the resulting property rush brought a large number of landed gentry and yeoman families into the area, so that two thirds of the burgesses were actually from the rural area around the town.[9] Francis Wolryche's stake in Hughley gave Thomas Wolryche a foothold in the liberty that could be exploited through his uncle's influence.

Wolryche was elected Member of Parliament for Wenlock on 2 January 1621[9] and was made a freeman of the borough on the same day.[2] He was re-elected MP for Wenlock on 22 January 1624 to the last parliament of the reign of James I and on 2 May 1625 to the first parliament of Charles I's reign.[9] These were times of increasing tension between Crown and Parliament. However, Wolryche made no impact on the proceedings of the House of Commons, although he was appointed to a few committees, and on one occasion turned up for the meetings of a committee of which he was not a member.[2] His parliamentary career died naturally as his uncle ailed. He was succeeded by Francis Smallman in the elections of January 1626, apparently without a contest. Sir Edward Bromley died later in the year, leaving Wolryche plate to the value of £20.[4]

The Civil War

Prelude to war

Wolryche is regarded as a “zealous supporter of the king.”[1] However, his political mentor, Edward Bromley, who died before the political tension between Crown and Parliament developed into crisis, had been a moderate Puritan and a friend of Richard Hutton and John Denham,[4] judges who defied Charles I over ship money. Wolryche was a commissioner for Charles I's forced loan in 1627 and for the subsidy in 1628-9: both involving issues that led the king to dispense with parliament from 1629-40. However, he was not implicated in the politics of Charles I's attempt at absolute monarchy, known as Thorough. He was a local Justice of the Peace and, as a wealthy man, was nominated in 1632 to become High Sheriff of Shropshire by John Egerton, 1st Earl of Bridgewater, the president of the Council in the Marches of Wales but he was not pricked for the post.[2]

As tensions between Charles I and Parliament mounted in 1641, Charles courted support and raised funds simultaneously by creating numerous knights and baronets. Wolryche was knighted at Whitehall Palace on 22 July 1641[11] and created the first of the Wolryche baronets on 4 August 1641.[1] This was no guarantee of loyalty to the king when conflict came: a considerable part of the Shropshire landed gentry, including baronets and close relatives of Wolryche, was on the other side. His sister Elizabeth and her husband John Puleston were committed Presbyterians and she was forced to flee their Flintshire home.[12] The influence of the militantly royalist Francis Ottley, whose sister, Ursula, Wolryche had married in 1625,[13] seems to have been decisive in making him act for the king. Ottley, unlike Wolryche himself, was politically committed and well-informed, retaining a correspondent in London to help him follow developments.[14] Wolryche accepted a commission to collect the Poll Tax in 1641 and during the summer of 1642, with both Charles and Parliament mobilising for possible war, both he and Ottley received Commissions of array from the king.[2] Wolryche was already experienced in captaining a county militia company.

Shrewsbury was not a natural royalist stronghold as it had been the scene of political and ideological conflict between Puritans and Laudians for several decades.[15] A group of Shrewsbury aldermen petitioned parliament on 16 July to recognise a militia that had begun to gather under the command of Thomas Hunt.[16] Parliament responded positively and sent a deputation of three MPs to establish its military control of Shropshire. One of these was Sir John Corbet, 1st Baronet, of Stoke upon Tern, a grandson of Lord Chancellor Thomas Bromley[17] and thus Wolryche's second cousin. However, it was Francis Ottley who seized the initiative and disrupted the parliamentary muster on 1 August, allowing Royalist forces to rally the following day under Sir Vincent Corbet of Moreton Corbet.

On 8 August Wolryche was prominent among the county gentry who signed a “declaration and protestation” of the Grand Jury at the Shrewsbury Assizes. This was inspired by Ottley and stated:

- wee wilbee ready to attend and obey his maiestie in all lawfull wayes ffor the putting of the Countrey in a posture of Armes for the defence of his maiestie and the peace of this Kingdome And doe resolve according to our oathes of Supremacye and allegiance late protestacons to adventure our lives and fortunes in the defence of his Royall and sacred person and honor the true protestant religion The iust Priviledges of Parliament and the knowne lawes and liberties of the subiects That thereby the distractions and disturbances of his maiesties kingdome may bee reduced to his loyall government.[18]

The warmth of this support persuaded the king, on leaving his initial rallying point at Nottingham on 12 September, to head with his field army for Shrewsbury, which he reached on 20 September,[19] remaining until 12 October.[20] Ottley took effective control of Shrewsbury during the king's stay and, after some delay, was formally recognised as military governor of the town.[21] It was probably Ottley who recommended Wolryche for the post of governor of Bridgnorth. At some time early in the conflict, Wolryche was also appointed a Deputy Lieutenant of Shropshire.[2]

The defence of Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth's council had considered inserting a drawbridge into the bridge over the River Severn as early as 26 August, under a warrant from John Weld, the High Sheriff, but had decided on a compromise solution of rope and chain barriers.[22] Prince Rupert had arrived in the town on 21 September and ensured that two reliable, royalist bailiffs were elected for the following year: Thomas Dudley and John Farr.[23] Setting out from Shrewsbury on 12 October, the king arrived at Bridgnorth and stayed for three days with Sir William Whitmore at Bridgnorth Castle, billetting his army of 14,000 on the surrounding inhabitants,[24] before moving on to Wolverhampton.

Wolryche seems to have left the precautions for the town's defence largely to the council. Not until 29 November did they think even to set “watch and ward” at the direction of the bailiffs.[25] In December Wolryche's name was again prominent in an “Ingagement and Resolution of the Principall Gentlemen of the County of Salop,” pledging

- that we will do our uttermost endeavours, both by our selves and friends, to raise, as well for defence of our King and Countrey, as our own particular safeties, one entire regiment of Dragoneers, and with our lives to defend those men's Fortunes and Families that shall be Contributors herein, to their abilities.[26]

However, an embarrassing incident soon followed, in which Wolryche and his friends, in their desire to go on drinking as in peacetime, allowed a dangerous roundhead to evade capture. Wolryche, together with Sir William Whitmore, Edward Cresset and Sir Edward Acton were customers of John Birch, originally of Cannock and now a Bristol wine merchant. On 19 January they were at Bridgnorth, in the very act of making a deal, when a warrant arrived from Ottley, demanding Birch's arrest on the grounds that he “hath taken up Armes and is a disaffected p'son to our Sov'aigne Lord the Kinge and doth still persist therein as a traytor to his Royall person.”[27] Wolryche and the others wrote to Ottley the next day, offering to stand bail so that Birch could carry on his business with the local gentry until the following Thursday.[28] Evidently Birch continued to trade, albeit with some inconveniences, and on 28 January had the gall to write from Bristol to Ottley, claiming that there was an agreement to allow free trade between Bristol and Shrewsbury, and demanding restitution or compensation for four butts of sack, confiscated at Shrewsbury and worth, he alleged, the enormous sum of £64.[29] Birch soon appeared in arms on the side of Parliament, later waging a successful campaign against the royalists in Herefordshire.[30] Wolryche, Cresset and Acton, however, showed their loyalty to the royalist cause on 28 January by having a villager committed to the assizes for “speaking of words tending to high tresson.”[31]

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of Bridgnorth were taking steps to improve their own protection. On 25 January the council agreed to maintain nine dragoons at the expense of the town, although the force was assembled only by renting a horse and rider from Thomas Corbet of Longnor Hall and two horses from Thomas Glover, a townsman who demanded a shilling a day for each animal.[32] At the same time the watch was organised on more efficient military lines, with captains for day and night, and eight men assigned to the night watch, with six to the day. Corbet was persuaded to begin drilling the young men of the town and the surrounding area for its defence, although it was to Ottley he wrote on 5 February for support and validation.[33]

In March 1643 Wolryche took a small force out of the county to support a royalist attack on Lichfield.[2] His progress was marked by a report from Walter James, Ottley's informant at Newport, Shropshire, that he had insisted on opening the posts between Birmingham and Nantwich,[34] apparently discovering material of interest. On his return, Wolryche was faced in May by a much more rigorous set of demands from the town council, based on a directive from Lord Capell, the regional royalist commander:

- to draw his forces of the trayned band of this county which are under his command, to this towne and neighbourhood hereabouts of Bridgnorth; it is agreed that fortifications be made in all fords and places about this towne, and the liberties thereof, where the said Thomas Wolrich shall think good to appoint, and that all the men of this towne shall come themselves, or send labourers to this work, with all speed ; unto which work Edward Cressett, Esq., and Edward Acton, Esq., justices of peace of the said county, being present, do promise to send labourers and workmen out of the country. Secondly, whosoever has volunteered will bear arms for the defence of this towne, and the neighbourhood hereabouts, shall be listed, and attend the service of training weekly, upon every Tuesday, to be exercised therein, whose teaching and training for that service Lieutenant Billingsley (at the towne's entreaty) is pleased to undertake.[35]

Francis Billingsley seems to have brought a measure of professionalism to the defence of Bridgnorth. Wolryche, however, seems never to have fully reconciled himself to the demands of war. In June he wrote to Capell to denounce a constable of Halesowen,[36] then in Shropshire, who had been insufficiently vigorous in levying taxation, requisitioning and conscripting for the king. Nevertheless, when a relative, Gilbert Warley, protested to him about the exactions of a royalist foraging party on his neighbours, Wolryche was quick to write to Ottley, asking for his help in recovering horses stolen in the incident.[37]

Ottley was removed from the governorship of Shrewsbury in February 1644, under pressure from Prince Rupert. It seems that Wolryche too was replaced at some time early in 1644,[2] perhaps on the same occasion, as Rupert visited Bridgnorth on his way to Shrewsbury.[38] His replacement was Sir Lewis Kirke, the brother of David Kirke,[39] and like him a tough soldier and adventurer honed by his experiences in Canada. Kirke and Billingsley established a small committee to manage the fortification and defence of Bridgnorth.[40] However, Kirke was later accused of using torture in his attempts to suppress internal opposition in the town.[39]

Defeat and aftermath

Wolryche remained active until at least August 1645.[2] The guidebook to Dudmaston, by transposing the parliamentary encirclement to 1644 and omitting to mention Wolryche's removal, implies that he was involved in the siege of the castle and the destruction of the town.[41] He was not present at the taking of Bridgnorth, which took place on 21 March 1646,[42] when the commander was still Kirke. The garrison set fire to the town, which was largely destroyed, as an inscribed tablet on the North Gate Museum makes clear. This was in response to a volley of stones rained on them by the townspeople as they were retreating into the castle,[43] suggesting that the population generally was hostile to the royalist occupation, at least by this stage. The damage was valued at £60,000.[42]

A possible source of confusion is that Wolryche surrendered to Parliament on especially lenient terms, as did the defenders of Bridgnorth Castle under the so-called Bridgnorth Articles, agreed on 26 April 1646.[44] only to surrender shortly afterwards. Wolryche was imprisoned once and sequestered twice.[1] On 11 March 1647 he was fined £730, only a tenth the value of his estates.[2] However, this was because of an appeal made on his behalf by William Pierrepont, the MP for Much Wenlock, and much to the chagrin of the parliamentary committee for Shropshire. Wolryche still had considerable debts in 1657, when he made a will assigning his estates to Pierrepont and his third son, William Wolryche, in a scheme to repay them. This arrangement he later altered.

Death

Wolryche died on 4 July 1668, aged 70 and was buried at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury on 9 July 1668.[1] He has a memorial inscription on a cenotaph tomb in the family's shrine church of St Andrew at Quatt.

Marriage and family

Wolryche married Ursula Ottley, daughter of Thomas Ottley of Pitchford, Shropshire, in Pitchford parish church on 4 May 1625.[13] The couple had seven sons and two daughters.[2] Evidently Ursula Ottley too returned to the parental home for the first few births, as it is the Pitchford parish register that records the baptism of the first child, Margaret, on 30 May 1626,[13] of Francis, the first son, on 21 October 1627,[45] of Roger on 14 December 1628, as well as the much younger Andrew on 25 April 1644.[46]

Francis automatically succeeded to the baronetcy but his mental illness prevented his taking responsibility for the property. The estates were put in trust with John,[47] the fifth but third surviving son, and the situation was regularised by a private act of Parliament in 1673. John was elected MP for his father's constituency of Much Wenlock in August 1679 and February 1681.[48] John died in 1685, three years before Francis, but it was his son, Thomas who inherited both the baronetcy and the estates in 1688.[1]

Family tree

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 George Edward Cokayne Complete Baronetage, Volume 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Thrush and Ferris: WOLRYCHE (WOOLRIDGE), Thomas (1598-1668), of Dudmaston, Salop. – Author: Simon Healy

- ↑ Grazebrook and Rylands, p. 509

- 1 2 3 Will of Sir Edward Bromley, in Fletcher, p.71-72

- ↑ Thrush and Ferris: BROMLEY, Edward (1563-1626), of the Inner Temple, London and Hallon, Worfield, Salop – Author: Simon Healy

- ↑ "Wolryche, Thomas (WLRC614T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Inderwick, p.91

- ↑ C R J Currie (Editor), A P Baggs, G C Baugh, D C Cox, Jessie McFall, P A Stamper (1998). "Hughley". A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 10: Munslow Hundred (part), The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Thrush and Ferris: Much Wenlock – Author: Simon Healy

- ↑ C R J Currie (Editor), A P Baggs, G C Baugh, D C Cox, Jessie McFall, P A Stamper (1998). "The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock". A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 10: Munslow Hundred (part), The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ Shaw, p.210

- ↑ Orr, D.A. "Puleston, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22873. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 Horton, p.12

- ↑ Phillips (1894), p.29-32

- ↑ Coulton, p.69-90

- ↑ Coulton, p.91

- ↑ Cust, Richard. "Corbet, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6288. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.242

- ↑ Sherwood, p.4

- ↑ Sherwood, p.13

- ↑ Wright, Stephen. "Ottley, Sir Francis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20940. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Bellett, p.131

- ↑ Bellett, p.134-5

- ↑ Sherwood, p.14

- ↑ Bellett, p.140

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.254-5

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.257

- ↑ Phillips (1894), p.63.

- ↑ Phillips (1894), p.66.

- ↑ Henning: BIRCH, John (1615-91), of The Homme, nr. Leominster and Garnstone Manor, Weobley, Herefs. - Author: John. P. Ferris.

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.272

- ↑ Bellett, p.140-1

- ↑ Phillips (1894), p.74-5

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.276

- ↑ Bellett, p.142-3

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.329

- ↑ Phillips (1895), p.347-8

- ↑ Sherwood, p.89

- 1 2 Moir

- ↑ Bellett, p.144

- ↑ Garnett, p.24

- 1 2 Sherwood, p.152

- ↑ Bellett, p.166

- ↑ The full text is given by Bellett, p.229ff.

- ↑ Horton, p.13

- ↑ Horton, p.15

- ↑ Henning: WOLRYCHE, John (c.1637-85), of Dudmaston Hall, Quatt, Salop. – Authors: J. S. Crossette / John. P. Ferris

- ↑ Henning: Much Wenlock – Author: J. S. Crossette

References

- "Wolryche, Thomas (WLRC614T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- G. Bellett (1856). The Antiquities of Bridgnorth, Longmans. Accessed 2 June 2014 at Internet Archive.

- George Edward Cokayne (1900). Complete Baronetage, Volume II, 1625-1649, Exeter: William Pollard. Accessed 26 May 2014 at Internet Archive.

- Barbara Coulton (2010). Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400-1700, Logaston Press ISBN 978 1 906663 47 6.

- C R J Currie (Editor), A P Baggs, G C Baugh, D C Cox, Jessie McFall, P A Stamper (1998). A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 10 - Munslow Hundred (part), The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock, Institute of Historical Research. Accessed 27 May 2014.

- Cust, Richard. "Corbet, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6288. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- W. G. D. Fletcher. Lady Margaret Bromley, in Transactions of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society, volume 8, 1893-4. Accessed at Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, 19 May 2014.

- Oliver Garnett (2005). Dudmaston, The National Trust, ISBN 9781843590149.

- George Grazebrook and John Paul Rylands (editors) (1889). The Visitation of Shropshire, taken in the year 1623: Part II, Harleian Society. Accessed 26 May 2014 at Internet Archive.

- T.R. Horton (editor) (1900): The Registers of Pitchford Parish, Shropshire, 1558–1812, Shropshire Parish Register Society. Accessed 26 May 2014 at Internet Archive.

- Henning, B.D. (1983). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690. Boydell and Brewer. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Frederick Andrew Inderwick (editor) (1896).A Calendar of the Inner Temple records, volume 2, Masters of the Bench and H. Sotheran. Accessed 19 May 2014 at Internet Archive.

- John S. Moir. KIRKE, SIR LEWIS, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 2, 2014.

- Orr, D.A. "Puleston, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22873. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Phillips, William, 1894: The Ottley Papers relating to the Civil War, in Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 2nd series, vol. VI, 1894, p. 27-78 accessed 26 May 2014 at Internet Archive.

- Phillips, William, 1895: The Ottley Papers relating to the Civil War, in Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 2nd series, vol. VII, 1895, p. 241-360 accessed 26 May 2014 at Internet Archive

- William A. Shaw (1906). The Knights of England, volume 2, Sherratt and Hughes. Accessed 26 May 2014 at Open Library.

- Roy Sherwood (1992). The Civil War in the Midlands 1642-1651, Alan Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0 7509 0167 5.

- Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (1982). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629. Boydell and Brewer. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Wright, Stephen. "Ottley, Sir Francis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20940. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)Subscription required: free to most UK public library members.

| Parliament of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Rowland Lacon Edward Lawley |

Member of Parliament for Wenlock 1621-1625 With: Sir Edward Lawley 1621-1622 Henry Mytton 1624 Thomas Lawley 1625 |

Succeeded by Thomas Lawley Francis Smallman |