Siege of Marienburg (1410)

| Siege of Marienburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War | |||||||

Polish artillery shelling Marienburg Castle in 1410 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Jogaila Vytautas the Great | Heinrich von Plauen | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,000 Poles 11,000–12,000 Lithuanians[1] 800 Moldavians |

3,000 reserve men 1,427 Grunwald survivors 200 seamen from Danzig (Gdańsk)[2] | ||||||

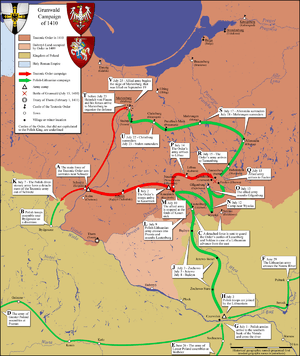

The Siege of Marienburg was an unsuccessful two-month siege of the castle in Marienburg (Malbork), the capital of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights. The joint Polish and Lithuanian forces, under command of King Władysław II Jagiełło and Grand Duke Vytautas, besieged the castle between 26 July and 19 September 1410 in a bid of complete conquest of Prussia after the great victory in the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg). However, the castle withstood the siege and the Knights conceded only to minor territorial losses in the Peace of Thorn (1411). Marienburg defender Heinrich von Plauen is credited as the savior of the Knights from complete annihilation.

Background

Allied Polish and Lithuanian forces invaded Prussia in July 1410 with a goal of capturing Marienburg. Their path was blocked by the Teutonic Knights, who engaged the allied forces in the decisive Battle of Grunwald on 15 July 1410. The Knights suffered a great defeat, leaving most of their leadership dead or captured. The victorious Polish and Lithuanian forces stayed on the battlefield for three days; during this time Heinrich von Plauen, Komtur of Schwetz (Świecie), organized defense of Marienburg.[1] Von Plauen did not participate in the battle and was trusted to command reserve forces of about 3,000 men in Schwetz. It is not entirely clear whether von Plauen marched to Marienburg based on pre-battle instructions of Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen or on his own initiative to fill the leadership void.[1] As the Polish–Lithuanian forces moved on to Marienburg, three Teutonic fortresses – Hohenstein (Olsztynek), Osterode (Ostróda), and Christburg (Dzierzgoń) – surrendered without resistance.[1] The allied forces moved slowly, averaging only about 15 km (9.3 mi) per day, giving time for von Plauen to organize the defense. This delay has been criticized by modern historians as one of the greatest Polish–Lithuanian tactical mistakes and has been a subject of much speculation.[3][4] Polish historian Paweł Jasienica suggested, for example, that Jagiełło might have intentionally gave the Knights time to regroup, to keep the humbled but not decimated Order as to not upset the balance of power between Poland (which would most likely acquire most of the Order possessions if it was totally defeated) and Lithuania; but a lack of primary sources precludes a definitive explanation.[5]

Siege

The main Polish–Lithuanian forces arrived only on 26 July 1410.[2] The day before von Plauen ordered the town outside the Marienburg Castle to be burned, depriving allied soldiers of shelter and clearing the battlefield.[6] The siege was not intense: Polish King Jogaila was confident that Prussia had already fallen and began distributing land among his nobles. He sent his troops to capture numerous small castles that were left without garrisons.[7] Only eight castles remained in Teutonic hands.[8] The Knights were allowed to communicate with their allies.[2] They send envoys to Sigismund of Hungary and Wenceslaus, King of the Romans, who provided a loan to hire mercenaries and promised to send Bohemian and Moravian reinforcements by the end of September. The Livonian Order sent 500 men as soon as its three-month truce with Lithuania expired.[2] The siege, holding Jogaila's army in place, helped to organize defensive forces in other parts of Prussia.[9] The besiegers expected capitulation and were not prepared for a long-term engagement, suffering from lack of ammunition, low morale, and an epidemic of dysentery.[10] The nobles wanted to return home for the harvest and the mercenaries wanted to get paid. Lithuanian troops, commanded by Vytautas, were the first to withdraw.[10] The siege was eventually lifted on 19 September. Before departing, Jogaila built a stronghold in Stuhm (Sztum), south of Marienburg, hoping to keep pressure on the Knights.[11] The Polish–Lithuanian forces returned to Poland and Lithuania, leaving Polish garrisons in fortresses that surrendered or were captured.[10]

Aftermath

After the withdrawal of the Polish–Lithuanian forces, the Knights started taking back their fortresses. By the end of October, only four Teutonic castles remained in Polish hands – border towns of Thorn (Toruń), Nessau (Nieszawa), Rehden (Radzyń Chełmiński) and Strasburg (Brodnica).[12] Jogaila raised a fresh army and dealt another defeat to the Knights in the Battle of Koronowo on 10 October 1410.[13] Von Plauen, using his reputation as hero of Marienburg, was selected as the new Grand Master in November. Von Plauen wanted to continue warfare, but he was pressured by his advisers into peace negotiations.[14] The Peace of Thorn was signed on 1 February 1411. It is considered a diplomatic victory for the Knights as they suffered only minimal territorial losses. The Siege of Marienburg and subsequent Peace of Thorn are seen as disappointing results of the great Battle of Grunwald.[7]

The Marienburg Castle was again defended by the Teutonic Order in 1454 but was captured by Poles in 1457 during the subsequent Thirteen Years' War (1454–66).[15]

References

- Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Turnbull 2003, p. 73

- 1 2 3 4 Turnbull 2003, p. 74

- ↑ Urban 2003, p. 162

- ↑ Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5.

- ↑ Paweł Jasienica (1978). Jagiellonian Poland. American Institute of Polish Culture. pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Urban 2003, p. 161

- 1 2 Urban 2003, p. 164

- ↑ Ivinskis 1978, p. 342

- ↑ Urban 2003, p. 163

- 1 2 3 Turnbull 2003, p. 75

- ↑ Urban 2003, p. 165

- ↑ Urban 2003, p. 166

- ↑ Turnbull 2003, p. 76

- ↑ Urban 2003, pp. 172–173

- ↑ Michał Rusinek (November 1973). Land of Nicholas Copernicus. Twayne. p. 27.

- Bibliography

- Ivinskis, Zenonas (1978), Lietuvos istorija iki Vytauto Didžiojo mirties, Rome: Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademija, LCC 79346776 (Lithuanian)

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Tannenberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights, Campaign Series, 122, London: Osprey, ISBN 978-1-84176-561-7

- Urban, William (2003), Tannenberg and After: Lithuania, Poland and the Teutonic Order in Search of Immortality (Revised ed.), Chicago: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, ISBN 0-929700-25-2