Shina (word)

| Shina | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 支那 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | chi na | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 지나 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 支那 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 支那 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | シナ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shina (支那, pronounced [ɕiꜜna]) is a largely archaic Japanese name for China. The word was originally used neutrally in both Chinese and Japanese, but came to be perceived as derogatory by the Chinese during the course of the Sino-Japanese Wars. As a result, it fell into disuse following the Second World War, was replaced by chūgoku (中国), and is now viewed as an offensive, derogatory label by scholars especially when used in bad faith.[1][2]

Sanskrit

The Sanskrit word Cina (चीन IPA: /c͡çiːnə/), for China, was transcribed into various forms including 支那 (Zhīnà), 芝那 (Zhīnà), 脂那 (Zhīnà) and 至那 (Zhìnà). Thus, the term Shina was initially created in Chinese as a transliteration of "Cina." This term was in turn brought to Japan with the spread of Chinese Buddhism. Traditional etymology holds that the Sanskrit name derives from the Qin state or dynasty (秦, Old Chinese: *dzin) which ruled China in 221–206 BC. Thus, the Sanskrit name for Qin came back to China in a different form, just as Qin would be at the root of Middle Persian Čīn (چین), and Latin Sina.

Chinese

Below is a Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907) poem titled Ti Fan Shu (literally "preface to a Sanskrit book") by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang using the Chinese term Zhina (支那) to refer to China:

《題梵書》

穿耳胡僧笑點頭。

鶴立蛇形勢未休,

五天文字鬼神愁。

支那弟子無言語,

At first, it was widely accepted that the term "Shina" or "Zhina" had no political connotations. In fact, before the Republican era, the term "Shina" was one of the names proposed as a "generalized, basically neutral Western-influenced equivalent for 'China.'" Chinese revolutionaries, such as Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren, and Liang Qichao, used the term extensively, and it was also used in literature as well as by ordinary Chinese. The term "transcended politics, as it were, by avoiding reference to a particular dynasty (the Qing) or having to call China the country of the Qing". With the overthrow of the Qing in 1911, however, most Chinese dropped Shina as foreign and demanded that Japan replace it with the Japanese reading of the Chinese characters used as the name of the new Republic of China 中華民國 (chūkaminkoku), with the short form 中國 (chūgoku).[3]

Latin

The Latin term for China was Sinae, plural of Sina. When Arai Hakuseki, a Japanese scholar, interrogated the Italian missionary Giovanni Battista Sidotti in 1708, he noticed that "Sinae", the Latin plural word Sidotti used to refer to China, was similar to Shina, the Japanese pronunciation of 支那. Then he began to use this word for China regardless of dynasty. Since the Meiji Era, Shina had been widely used as the translation of the Western term "China". For instance, "Sinology" was translated into "Shinagaku" (支那學).

Japanese

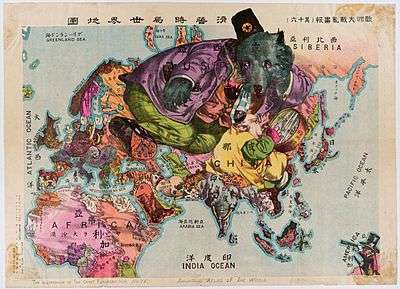

The First Sino-Japanese War caused the view that it had a negative nuance to gradually spread among the Chinese.

Nevertheless, the term continued to be more-or-less neutral. A Buddhist school called Zhīnà Nèixuéyuàn (支那內學院) was established as late as in 1922 in Nanjing. In the meantime, "Shina" was used as commonly in Japanese as "China" in English. Derogatory nuances were expressed by adding extra adjectives (e.g. 暴虐なる支那兵 ("cruel Shina soldiers") or using derogatory terms like chankoro (チャンコロ), originating from a corruption of the Taiwanese Hokkien pronunciation of 清國奴 Chheng-kok-lô͘, used to refer to any "chinaman", with a meaning of "Qing dynasty's slave".

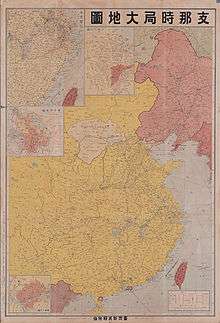

Despite interchangeability of Chinese characters, Japan officially used the term Shina Kyōwakoku (支那共和国) from 1913 to 1930 in Japanese documents, while Zhonghua Minguo (中華民國) was used in Chinese ones. "Shina Kyōwakoku" was the literal translation of the English "Republic of China" while Chūka Minkoku was the Japanese pronunciation of the official Chinese characters of "Zhonghua Minguo". The Republic of China unofficially pressed Japan to adopt the latter but was rejected.

Japan rejected the term "Chūka Minkoku" for four different reasons: (1) the term referring to China (then Republic) as "the center of the world" was arrogant; (2) Western countries used "China"; (3) Shina was the common name in Japan for centuries; (4) Japan already has a Chugoku, in its western region. The name "Chūka Minkoku" was officially adopted by Japan in 1930 but "Shina" was still commonly used by the Japanese throughout the 1930s and 1940s.[1]

Japan today

The Second Sino-Japanese War fixed the impression of the term "Shina" as offensive among Chinese people. In 1946, the Republic of China demanded that Japan cease using "Shina".

In China, the term Shina has become linked with the Japanese invasion and Japanese war crimes, and has been considered a derogatory and deeply offensive ethnic slur ever since. Although many assume that the term was created (or chosen) by the Japanese for exclusive use as a racist term, since the character 支 (Japanese: shi; Chinese: zhī) means "branch" which could be interpreted to suggest that the Chinese are subservient to the Japanese, the characters were originally chosen simply for their sound values, not their meanings.

In modern Japan, the term 中華民国 refers to the Republic of China, 中華人民共和国 refers to the People's Republic of China; the terms being used similarly in the Western world and unofficially in both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China.

It is considered socially unacceptable and subject to kotobagari, especially the kanji form (if Shina is used, it is now generally written in katakana). However, even then it is still sometimes seen in written forms such as shina soba (支那そば), an alternative name for ramen, which originates from China. Many Japanese are not fully aware of Chinese feelings towards the term, and generally find Shina merely old-fashioned and associated with the early and mid-20th century, rather than derogatory and racist. This difference in conception can lead to misunderstandings.

A few compound words containing Shina have been altered; for example, the term for Sinology was changed from Shinagaku (支那学) ("Shina-studies") to Chūgokugaku (中国学) ("Chinese studies"), and the name for the Second Sino-Japanese War has changed from terms such as Shina jihen (支那事變) ("The China Incident"), Nisshi jihen (日支事變) ("The Japan-Shina Incident") and Nitchū sensō (日中戦争) ("Japan-China War").

On the other hand, the term Shina / Zhina has survived in a few non-political compound words in both Chinese and Japanese. For example, the South and East China Seas are called Minami Shina Kai (南シナ海) and Higashi Shina Kai (東シナ海) respectively in Japanese (prior to World War II, the names were written as 南支那海 and 東支那海), and one of the Chinese names for Indochina is Yindu Zhina (印度支那 Indoshina). Shinachiku (支那竹 or simply シナチク), a ramen topping made from dried bamboo, also derives from the term "Shina", but in recent years the word menma (メンマ) has replaced this as a more politically correct name. Some terms that translate to words containing the "Sino-" prefix in English retain Shina within them, albeit written in katakana, for example シナ・チベット語族 (Sino-Tibetan languages) and シナントロプス・ペキネンシス (Sinanthropus pekinensis, also known as Peking Man).

Sinologist, historian professor Joshua A. Fogel mentioned that "Surveying the present scene indicates much less sensitivity on the part of Chinese to the term Shina and growing ignorance of it in Japan". He also criticized Ishihara Shintarō (石原慎太郎), a rightwing politician who went out of his way to use the expression “Shinajin (支那人) and called him a "troublemaker".[1]

He also indicated that: "Many terms have been offered as names for countries and ethnic groups that have simply not withstood the pressures of time and circumstance and have, accordingly, changed. Before the mid-1960s, virtually every well-meaning American, black or white and regardless of political affinity, referred to blacks as 'Negroes' with no intention of offense or slight. It was simply the respectful name in use; and it was superior to the openly reviled and offensive term “colored,” still in legal use by Southern bigots (to say nothing of the highly offensive term in colloquial use by this group)... By the late 1960s, few if any liberals were still using 'Negro' but had shifted to 'black,' because that was declared the ethnonym of choice by the group so named."[1]

Japanese Canadian historian Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi mentioned that there are two classes of postwar Japanese have continued to use derogatory terms like Shina: poorly educated and/or elderly persons who grew up with the term go on using these from force of habit.[2]

Some right-wing Japanese appeal to etymology in trying to ascribe respectability to the continued use of Shina, since the term Shina has non-pejorative etymological origins. Wakabayashi said: "The term Jap also has non-pejorative etymological origins, since it derives from Zippangu (ジパング) in Marco Polo's Travels... If the Chinese today say they are hurt by the terms Shina or Shinajin, then common courtesy enjoins the Japanese to stop using these terms, whatever the etymology or historical usage might be."[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Joshua A. Fogel, “New Thoughts on an Old Controversy: Shina as a Toponym for China” Sino-Platonic Papers, 229 (August 2012)

- 1 2 3 Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, "The Nanking Atrocity, 1937-38: Complicating the Picture" (2007), Berghahn Books, p395-398

- ↑ Douglas R. Reynolds. China, 1898–1912: The Xinzheng Revolution and Japan.(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1993 ISBN 0674116607), pp. 215–16 n. 20.

Further reading

- Joshua A. Fogel, "The Sino-Japanese Controversy over Shina as a Toponym for China," in The Cultural Dimension of Sino-Japanese Relations: Essays on the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, ed. Joshua A. Fogel (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1995), 66–76.

- Lydia He Liu. The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004). ISBN 0674013077), esp. pp. 76–79.