Shale gas in the United Kingdom

Shale gas in the United Kingdom has attracted increasing attention since 2007, when onshore shale gas production was proposed. A number of wells have been drilled, and favourable tax treatment has been offered to shale gas producers.[1]

In July 2013 UK Prime Minister David Cameron had claimed that, "fracking has real potential to drive energy bills down".[2] However, in November 2013 representatives from industry and government, such as former BP Chief Executive and government advisor Lord Browne, Energy Secretary Ed Davey and economist Lord Stern said that fracking in the UK alone will not lower prices as the UK is part of a well connected European market.[3][4][5] As of December 2014, there has been no commercial production of shale gas in the UK.

Areas

The Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) originally identified large areas of eastern and southern England as having the "best shale gas potential":

The main area identified runs from just south of Middlesbrough in a crescent through East Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire and the Cotswolds to Somerset and Wiltshire. It then turns along the South Coast and Downs, including most of Dorset, Hampshire, Sussex, Surrey and Kent. Shale gas sites are under investigation in the Sussex commuter belt, near Haywards Heath, the Mendip Hills, south of Bath, in Kent, Lincolnshire, south Wales, Staffordshire and Cheshire, as well as more sites near the existing find in Lancashire.[6]

However the British Geological Survey report released in October 2014 said that there was little potential for shale gas in the Weald Basin as the field has not yet reached thermal maturation, however may exhibit oil-shale potential. (see 'Weald Basin' below)

Bowland Basin

As of June 2013, the Bowland Basin was the only area in the UK where wells have been drilled specifically for shale gas. Four wells have been drilled by Cuadrilla Resources, and one by IGAS Energy. None of the wells have produced gas.

Cuadrilla started drilling Britain's first shale gas exploration well, the Preese-Hall-1, in August 2010. The well penetrated 800m of organic-rich shale. The company hydraulically fractured the well in early 2011, but suspended the operation when it triggered two seismic events of magnitudes (ML) 2.3 and 1.5, the larger of which was felt[7] by at least 23 people at the surface.[8] Work on the well stopped in May 2011, and the government declared a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing that was sustained until December 2012, subject to additional controls to limit seismic risk.[9][10][11]

In September 2011, Cuadrilla announced a huge discovery of 200 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas in place under the Fylde Coast in Lancashire.[12][13] Cuadrilla stated that it would be happy if it could recover 10–20% of the gas in place.[14] Lord Browne ignored this latter point in media interviews, claiming that the Lancashire discovery could satisfy the UK's gas consumption "for 56 years",[15] with similar, sensational media reports claiming that the find was "so rich it could meet Britain's needs for decades",[16] or that it had "the potential to do more for Lancashire than the cotton industry."[17] (For comparison, the cotton industry in Lancashire employed, at peak penetration in 1811, 37% of the county, or about 70,000 people; Cuadrilla believes fracking will create 1,700 jobs in Lancashire, current population 1.1m).[18][19][20] The British Geological Survey—responsible for producing inventories of the UK's mineral resources, and far more cautious in its estimates—felt prompted, however, to re-evaluate its projections in light of the find,[21] which Cuadrilla believes could provide 5,600 jobs in the UK at the peak of production.[22] Industry estimates suggest shale gas in Lancashire alone could deliver £6bn of gas a year for the next three decades.[23]

In July 2013, Cuadrilla applied for a permit to hydraulically fracture its previously drilled well at the Grange Hill site.[24] In April 2014, Cuadrilla published news of their continuing consultation with residents shale gas exploration sites in the Fylde.[25]

In 2011 and 2012, IGas Energy drilled a deep well to evaluate shale gas, and found gas shows in the Bowland Shale, with total organic content averaging 2.7%. The formation was reported to be thermally mature, in the wet gas window. IGAS bought large blocks of gas licences in 2011, much of which is reportedly prospective for shale gas.[26]

IGas announced that it would drill a well to evaluate shale gas at Barton, near Manchester. Drilling would begin in October 2013, and take two to three months. IGas has not applied for a permit to hydraulically fracture the well.[27]

Weald Basin

A BGS/DECC report from May 2014 indicates that there is little potential for shale gas fracturing in the Weald Basin, south of London. It does suggest that there is the possibility for the extraction of light tight oil from shales (LTO)[28] Subsequent exploration showed a potentially major oil field near Gatwick Airport.[29]

Northern Ireland

According to February 2013 reports from PricewaterhouseCoopers, there could be £80 billion in reserves in Northern Ireland, although these claims were criticised as being sensationalist.[30]

Resource estimates

According to a 2011 report of the Energy and Climate Change Select Committee, "Shale gas resources in the UK could be considerable—particularly offshore—but are unlikely to be a "game changer" to the same extent as they have been in the US, where the shale gas revolution has led to a reduction in natural gas prices."[31] The Committee's chairperson, Tim Yeo, revised his personal opinion in 2012, however, and argued shale gas is a "game changer" that could "transform the UK's energy independence".[32][33] Interest in fracking came just as imports of gas to the UK had surpassed domestic production in 2011 for the first time since the 1960s.[34]

Estimating the size of recoverable resource is difficult due to the uncertainty of the usually small percentage of shale gas that is recoverable. In addition, companies may embrace large estimations of reserves to boost share prices. In the United States, companies had been subpoenaed in 2011 on suspicion that the projections they provided to investors, including press-release figures, were inflated. In 2012, national agencies in the U.S and Poland revised dramatically downward their estimates of shale gas resources.[35][36]

Part of the problem in evaluation is also the uncertainty of decline curve analysis from early data: shale gas wells can fall off sharply during the first year or two, then level off to a slower decline rate; the shape of the curve, and therefore the ultimate recovery, is difficult to predict from early production rates.[37]

Before drilling, IGas estimated gas in place of 4.6 Tcf in the Ince Marshes site, though it was unlikely that more than 20% of it could be recoverable;[38] After drilling their first well, IGas announced that the estimated gas in place was at least double their previous estimate.[39]

In early 2012, Celtique Energie estimated that there might be as much as 14 Tcf of recoverable reserves in countryside south of Horsham, West Sussex.[40] Preliminary estimates in 2011 suggested that there may be £70bn worth of shale gas in South Wales,[41] and 1.5bn bbl oil equivalent in Northern Ireland according to a report by PwC.[42]

British Geological Survey

In June 2013, the British Geological Survey estimated the gas in place within the Bowland Shale of central Britain to be within the range of 822 TCF to 2281 TCF, with a central estimate of 1,329 trillion cubic feet (37,600 km3), but did not estimate how much of the gas was likely to be recoverable,[43][44] and cautioned:

- "Estimates of the amount of recoverable gas and the gas resources are variable. It is possible that the shale gas resources in UK are very large. However, despite the size of the resource, the proportion that can be recovered is the critical factor."[45]

Industry estimates were that about 10% of gas in place could be extracted.[46] 130 TCF would supply Britain's gas needs for about 50 years.[47][48]

Comment from the British Geological Survey suggested even more substantial shale gas reserves offshore.[49]

US Energy Information Administration

In June 2013, the US Energy Information Administration issued a world-wide estimate of shale gas, which included an incomplete estimate of recoverable shale gas resources in the UK. The Carboniferous shale basins of North of England and Scotland, which include the Bowland Basin, were estimated to have 25 trillion cubic feet of recoverable shale gas. The Jurassic shales of the Wessex Basin and Weald Basin of southern England were estimated to have 600 billion cubic feet of recoverable shale gas and 700 million barrels of associated oil. The agency noted that the UK shale basins are more complex than those in the US, and therefore more costly to drill. On the other hand, as of June 2013, the price of natural gas in the United Kingdom was reported to be more than double the price in the US and Canada by one source[50] and three times higher by other sources.[51][52]

Climate change

Shale gas is largely methane, a hydrocarbon fuel. As such the carbon dioxide it produces contributes to global warming, although less so than coal. Of more concern is leaking or fugitive emissions of unburned methane, which is a greenhouse gas.[53] It has been argued that, in opening a new source of hydrocarbons, it may reduce the incentive and financing of renewable sources of energy.[54]

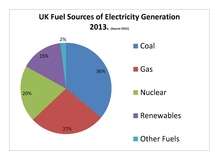

The 2008 Climate Change Act committed the UK to reducing CO2 emissions by 50% in 2030, and by 80% by 2050.[55] Currently the UK is generating more than 30% of its electricity from coal, and replacing this with shale gas would be one possible solution that provides reliable on demand electricity as it has a greenhouse gas equivalent value of about half that of coal.[56] Current National Grid energy sources can be seen on a live link [57]

In April 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its 5th Assessment report.[58] With regard to natural gas, and the shale gas debate, it states "GHG emissions from energy supply can be reduced significantly by replacing current world average coal‐fired power plants with modern, highly efficient natural gas combined‐cycle power plants or combined heat and power plants, provided that natural gas is available and the fugitive emissions associated with extraction and supply are low or mitigated (robust evidence, high agreement). In mitigation scenarios reaching about 450 ppm CO2eq concentrations by 2100, natural gas power generation without CCS acts as a bridge technology, with deployment increasing before peaking and falling to below current levels by 2050 and declining further in the second half of the century (robust evidence, high agreement)".

A 2013 government-sponsored study of the effect of large-scale natural gas development in Britain concluded that emissions from shale gas could be consistent with meeting climate change targets so long as the emissions were counteracted by similar size reductions elsewhere in the world, although the authors suggest that 'without global climate policies...new fossil fuel exploitation is likely to lead to an increase in cumulative carbon emissions and the risk of climate change'.[59]

In November 2014, the UK Energy Research Centre issued a report that stated "gas could play an important role as a ‘bridging fuel’ to a low-carbon economy, but warns that it won’t be long before gas becomes part of the problem rather than the solution". It noted that the UK imports more than half its gas, and that "gas use beginning to fall in the late 2020s and early 2030s, with any major role beyond 2035 requiring the widespread use of carbon capture and storage" [60] It also states "Instead of banking on shale, UKERC recommends rapidly expanding investment in alternative low-carbon energy sources and investing in more gas storage, which would help protect consumers against short-term supply disruption and price rises" [61][62][63]

Environmental impact

Groundwater contamination

The British Geological Survey, in reviewing the US experience with hydraulic fracturing of shale formations, observed: "where the problems are genuinely attributable to shale gas operations, the problem is with poor well design and construction, rather than anything distinctive to shale gas."[64]

Contamination of groundwater by methane can occur after the abandonment of the well: "Gas and other contaminants may accumulate slowly in these cracks, enter shallow strata or even leak at the surface many years after production or well abandonment. Even the presence of surface casing provides no assurance against gas leakage at the surface from the surrounding ground." [65]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Macalister 2013

- ↑ Macalister 2013 "Shale gas is a resource with huge potential to broaden the UK's energy mix," said the Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne. "We want to create the right conditions for industry to explore and unlock that potential in a way that allows communities to share in the benefits. "This new tax regime, which I want to make the most generous for shale in the world, will contribute to that. I want Britain to be a leader of the shale gas revolution – because it has the potential to create thousands of jobs and keep energy bills low for millions of people."

- ↑ Carrington 29 November 2013 In July, Osborne said: "This a real chance to get cheaper energy for Britain … a major new energy source that can reduce energy bills."In August, Cameron said: "If we don't back this technology, we will miss a massive opportunity to help families with their bills … fracking has real potential to drive energy bills down." In November, "the chairman of the UK's leading shale gas company", Lord Browne, said "Fracking is not going to reduce gas prices in the UK". "The statement by Lord Browne, one of the most powerful energy figures in Britain, contradicts claims by David Cameron and George Osborne that shale gas exploration could help curb soaring energy bills."

- ↑ The Telegraph 9 September 2013 "North Sea gas didn’t significantly move UK prices – so we can’t expect UK shale production alone to have any effect," Mr Davey said, pointing out that Britain is just one part of the wider European gas market. He said it was "far from clear that UK shale gas production could ever replicate the price effects seen in the US", where the shale gas boom has seen prices plummet. The comments stand in stark contrast to those of David Cameron, who wrote in the Telegraph last month that "fracking has real potential to drive energy bills down"

- ↑ The Independent 3 September 2013

- ↑ Gilligan 26 November 2011

- ↑ The Sun 2011A spokesman for Blackpool Police said: "We started to get calls at around 3.35am. "Some may have thought it was an April Fool prank, but staff here felt the building move.

- ↑ British Geological Survey 2011"Twenty-three reports of the shaking caused by the earthquake were used to determine earthquake intensity. We find a maximum intensity of 4 EMS close to the epicentre. This is consistent with a magnitude 2.3 earthquake at a depth of 3.5 km, however, the limited nature of the data means that this is also poorly constrained."

- ↑ Harrabin 2012

- ↑ Royal Society & Royal Aacademy of Engineering 2012

- ↑ Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) & The Rt Hon Edward Davey 2012

- ↑ Macalister 21 September 2011

- ↑ BBCLancashire 1 February 2013

- ↑ Gilligan 26 November 2011

- ↑ West 25 September 2011 Browne gets his headline-grabbing figure of 56 years by simply dividing the size of the entire Lancashire find, about 5.6 Tcm, by annual UK gas consumption, currently around 0.1 Tcm. Such a calculation takes no account of the fact that only a minority of the Lancashire discovery is recoverable.

- ↑ Leake 12 February 2012

- ↑ Clover 25 November 2011

- ↑ Walton 1987, p. 111

- ↑ Vision of Britain

- ↑ BBC 21 September 2011

- ↑ Leake 12 February 2012

- ↑ West 25 September 2011

- ↑ McKie 25 February 2012

- ↑ Reed 5 July 2013

- ↑ Cuadrilla Resources Ltd 23 April 2014

- ↑ US Energy Information Administration June 2013

- ↑ Gosden 9 September 2013

- ↑ Andrews 2014

- ↑ Goodway 22 March 2016

- ↑ Fowler 14 February 2013

- ↑ House of Commons:Energy and Climate Change Committee 23 May 2011

- ↑ Whipple 17 February 2012

- ↑ Webb 3 November 2011

- ↑ Gosden 29 March 2012

- ↑ Urbina 28 January 2012

- ↑ Strzelecki 2 March 2012

- ↑ Frean 20 October 2011 A typical well in North Dakota's seemingly prolific Bakken shale oil and gasfield, for example, may produce more than 1,000 barrels of oil per day in year [one], but only 200 in year two, according to Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources. Existing fracking methods are capable of extracting only 5 per cent of the oil content of the shale. This can be raised to 15 per cent by multiple extractions from each wellhead. Even then, 85 per cent of the oil remains below ground.

- ↑ Heren 26 January 2012

- ↑ IGas

- ↑ Gilligan 26 November 2011

- ↑ Rigby 1 July 2011

- ↑ Fowler 14 February 2013

- ↑ BBC News Business 27 June 2013

- ↑ Webb, Sylvester, Thomson 9 February 2013

- ↑ British Geological Survey

- ↑ BBC News Business 27 June 2013

- ↑ Chazan 10 January 2014

- ↑ Urquhart 11 January 2014

- ↑ Reuters 17 April 2012

- ↑ US Energy Information Administration June 2013

- ↑ BP web page, Retrieved 11 January 2014

- ↑ Reuters 25 March 2013

- ↑ DECC February 2014

- ↑ Aitkenhead 4 April 2014

- ↑ DEFRA, DECC, EA October 2014

- ↑ MacKay,Stone 9 September 2013

- ↑ National Grid power sources

- ↑ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2014

- ↑ MacKay,Stone 9 September 2013

- ↑ UK Energy Research Centre

- ↑ Gosden 12 November 2014

- ↑ UKERC 12 November 2014a

- ↑ UKERC 12 November 2014b

- ↑ British Geological Survey 2010

- ↑ Royal Society & Royal Aacademy of Engineering 2012, p. 26

References

- Macalister, Terry; Harvey, Fiona (19 July 2013). "George Osborne unveils 'most generous tax breaks in world' for fracking: Environmental groups furious as chancellor sets 30% rate for shale gas producers in bid to enhance UK energy security". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Carrington, Damian (29 November 2013). "Lord Browne: fracking will not reduce UK gas prices: Statement contradicts David Cameron and George Osborne's claims that shale gas could help curb soaring energy bills". The Guardian.

- "Fracking won't lower energy bills, says Davey: Fracking for shale gas in the UK will not have "any effect" on gas prices, Ed Davey, the energy secretary has said, contradicting the Prime Minister's promise that it will lead to lower energy bills.". The Telegraph. 9 September 2013.

- "'Baseless economics': Lord Stern on David Cameron's claims that a UK fracking boom can bring down price of gas": Respected economist criticises the Government for encouraging rush into fracking without a thorough analysis of all its potential ramifications". The Independent. 3 September 2013.

- Harrabin, Roger (13 December 2012). "Gas fracking: Ministers approve shale gas extraction". BBC News.

- Royal Society; Royal Academy of Engineering (28 June 2012). Shale gas extraction in the UK: a review of hydraulic fracturing (PDF) (Report).

- Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC); The Rt Hon Edward Davey (13 December 2012). "New controls announced for shale gas exploration" (Press release).

- Gilligan, Andrew (26 November 2011). "Field of dreams, or an environment nightmare?". Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Macalister, Terry (21 September 2011). "Vast reserves of shale gas revealed in UK". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- BBC News (1 February 2013). "Lancashire's Shale Gas Estimated at 136bn by Cuadrilla". BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- West, Karl (25 September 2011). "Enough gas in Lancashire 'to last Britain for 56 years'". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Leake, Jonathan (12 February 2012). "Gas find is enough to last 70 years". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Clover, Charles (25 November 2011). "Easing the energy crisis with a bit of Blackpool rock". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Walton, John K. (1987). Lancashire: a social history, 1558–1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 111.

- "Lancashire: Historical statistics—Population". Great Britain Historical GIS. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- BBC News (21 September 2011). "Shale gas firm finds 'vast' gas resources in Lancashire". BBC News. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- McKie, Robin (25 February 2012). "Fracking: answer to our energy crisis, or could it be a disaster for the environment?". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- Reed, Stanley (5 July 2013). "British company applies for shale gas fracking permit". The New York Times.

- "Cuadrilla update on Bowland exploration programme". News. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- US Energy Information Administration (June 2013). "XI". Technically recoverable shale oil and shale gas resources.

- Gosden, Emily (9 September 2013). "IGas Energy prepares to drill near Manchester". The Telegraph.

- Andrews, I. J. (2014). The Jurassic shales of the Weald Basin: geology and shale oil and shale gas resource estimation (pdf) (Report). London, UK: British Geological Survey for Department of Energy and Climate Change. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- Goodway, Nick (22 March 2016). "Outstanding' oil flow produced by Gatwick Gusher". The Independent. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Fowler, Julian (14 February 2013). "NI shale gas deposits 'could be worth £80bn' says report". BBC. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- House of Commons: Energy and Climate Change Committee (23 May 2011). Shale Gas: Fifth Report of Session 2010–12, Volume I (PDF). London: The Stationery Office. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Whipple, Tom (17 February 2012). "Controversial gas mining technique given green light by US expert study". The Times. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Webb, Tim (3 November 2011). "Blackpool earthquakes send shudder through hopes of onshore gas boom". The Times. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Gosden, Emily (29 March 2012). "UK gas imports outstrip production for first time since 1967". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- Urbina, Ian (28 January 2012). "New Report by Agency Lowers Estimates of Natural Gas in U.S.". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Strzelcki, Marek (2 March 2012). "Poland Says 22 Shale Gas Wells Under Way or Planned in 2012". Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Frean, Alexandra (20 October 2011). "American Notebook: Squeezing another drop from the barrel". The Times. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Heren (26 January 2012). "IGas finds vast shale gas reserves in newly acquired license". ICIS Heren. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "IGas Energy says Cheshire shale reserves more than double previous forecast". Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Rigby, Caroline (1 July 2011). "Shale gas fracking: call for Welsh Government policy". BBC News. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- BBC News Business (27 June 2013). "UK shale gas resources 'greater than thought'". BBC News business. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Webb, Tim; Sylvester, Rachel; Thomson, Alice (9 February 2013). "Britain has shale gas for 1,500 years, but bills won't be lower".

- British Geological Survey. "New shale gas resource figure for central Britain".

- Chazan, Guy (10 January 2014). "Total joins UK's pursuit of shale boom". The Financial Times. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Urquhart, Conol (11 January 2014). "French firm Total to join UK shale gas search". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Reuters (17 April 2012). "UK has vast shale gas reserves, geologists say". Reuters. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- BP. "Natural gas prices". Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Reuters (25 March 2013). "UPDATE 3-Britain's Centrica to buy U.S. natural gas in landmark deal". Reuters. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- DECC (February 2014). Fracking UK shale: climate change (PDF) (Report). Department of Energy & Climate Change. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- Aitkenhead, Decca (4 April 2014). "Caroline Lucas: 'I didn't do this because I thought it was fun'". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- DEFRA; DECC; EA. "2010-2015 government policy: greenhouse gas emissions". DECC. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- MacKay, David; Stone, Timothy (9 September 2013). Potential Greenhouse Gas Emissions Associated with Shale Gas Extraction and Use (PDF) (Report). Department of Energy & Climate Change. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- National Grid power sources. "National Grid power sources". BM Reports. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2014). "IPCC 2014: Summary for policymakers". In Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx. Climate Change 2014, Mitigation of Climate Change (PDF). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- "Gas can be a bridge to a low-carbon future". UK Energy Research Centre. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Emily, Gosden (12 November 2014). "Fracking won't cut bills and ministers 'oversold' shale gas benefits, experts say". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- UKERC (12 November 2014). "The UK's Global Gas Challenge". UKERC. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- UKERC (12 November 2014). "A Bridge to a Low-Carbon Future? Modelling the Long-Term Global Potential of Natural Gas". UKERC.

- British Geological Survey (2010). "The Unconventional Hydrocarbon Resources of Britain's Onshore Basins - Shale Gas" (PDF). Republished 2012. Department of Energy & Climate Change. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- British Geological Survey (2011). "Blackpool earthquake - Magnitude 2.3 - 1 April 2011". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "Blackpool rocked". The Sun. 1 April 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

External links

- The Geological Society, Shale gas

- UK Onshore Operators Group, UK Onshore Shale Gas Well Guidelines, February 2013.