Seminal vesicle

| Seminal vesicle | |

|---|---|

|

Human Male Anatomy | |

|

Prostate with seminal vesicles and seminal ducts, viewed from in front and above. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Wolffian duct |

| Artery | Inferior vesical artery, middle rectal artery |

| Lymph | External iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Vesiculae seminales |

| MeSH | A05.360.444.713 |

| FMA | 19386 |

The seminal vesicles (Latin: glandulae vesiculosae), vesicular glands,[1] or seminal glands, are a pair of simple tubular glands posteroinferior to the urinary bladder of some male mammals. Seminal vesicles are located within the pelvis. They secrete fluid that partly composes the semen.

Structure

The seminal vesicles are a pair of glands that are positioned below the urinary bladder and lateral to the vas deferens. Each vesicle consists of a single tube folded and coiled on itself, with occasional diverticula in its wall.[2]

The excretory duct of each seminal gland unites with the corresponding vas deferens to form the two ejaculatory ducts, which immediately pass through the substance of the prostate gland before opening separately into the verumontanum of the prostatic urethra.[2][3]

Each seminal vesicle spans approximately 5 cm, though its full unfolded length is approximately 10 cm, but it is curled up inside the gland's structure.

Development

Each vesicle forms as an outpocketing of the wall of the ampulla of one vas deferens. The seminal vesicles develop as one of three structures of the male reproductive system that develops at the junction between the urethra and vas deferens. The vas deferens is derived from the mesonephric duct, a structure that develops from mesoderm.[4]

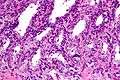

Histology

Under microscopy, the seminal vesicles can be seen to have a mucosa, consisting of a lining of interspersed columnar cells and a lamina propria; and a thick muscular wall. The lumen of the glands is highly irregular and stores secretions from the glands of the vesicles. In detail:[5]

- The epithelia is pseudostratified columnar in character, similar to other tissues in the male reproductive system.

The height of these columnar cells, and therefore activity, is dependent upon testosterone levels in the blood.

- The lamina propria, containing underlying small blood vessels and lymphatics. Together with the epithelia, this is called the mucosa, and is arranged into convoluted folds, increasing the overall surface area

- A muscular layer, consisting of an inner circular and outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle, can also be found.

Spermatozoa may occasionally be found within the lumen of the glands, even though the vesicles are blind-ended in nature. This is thought to be because of slight reflux due to muscular contractions of the urethra during ejaculation.[5]

Low magnification micrograph of seminal vesicle. H&E stain.

Low magnification micrograph of seminal vesicle. H&E stain. High magnification micrograph of seminal vesicle. H&E stain.

High magnification micrograph of seminal vesicle. H&E stain.

Function

The seminal vesicles secrete a significant proportion of the fluid that ultimately becomes semen. Lipofuscin granules from dead epithelial cells give the secretion its yellowish color. About 70-85%[6] of the seminal fluid in humans originates from the seminal vesicles, but is not expelled in the first ejaculate fractions which are dominated by spermatozoa and zinc-rich prostatic fluid. The excretory duct of each seminal gland opens into the corresponding vas deferens as it enters the prostate gland. Seminal vesicle fluid is alkaline, resulting in human semen having a mildly alkaline pH.[7] The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. Acidic ejaculate (pH <7.2) may be associated with ejaculatory duct obstruction. The vesicle produces a substance that causes the semen to become sticky and jelly-like after ejaculation.

The thick secretions from the seminal vesicles contain proteins, enzymes, fructose, mucus, vitamin C, flavins, phosphorylcholine and prostaglandins. The high fructose concentrations provide nutrient energy for the spermatozoa when stored in semen in the laboratory.

In vitro studies have shown that sperm expelled together with seminal vesicular fluid show poor motility and survival, and the sperm chromatin is less protected. Therefore, the exact physiological importance of seminal vesicular fluid is not clear.

The development and maintenance of the seminal vesicles, as well as their secretion and size/weight, are highly dependent on androgens.[8][9] The seminal vesicles contain 5α-reductase, which metabolizes testosterone into its much more potent metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT).[9] The seminal vesicles have also been found to contain luteinizing hormone receptors, and hence may also be regulated by the ligand of this receptor, luteinizing hormone.[9]

Clinical significance

Physical examination of the seminal vesicles is difficult. Laboratory examination of seminal vesicle fluid requires a semen sample, e.g. for semen culture or semen analysis. Fructose levels provide a measure of seminal vesicle function and, if absent, bilateral agenesis or obstruction is suspected.[10]

Disorders of the seminal vesicles include seminal vesiculitis, acquired cysts, abscess, congenital anomalies (such as agenesis, hypoplasia and cysts), amyloidosis, tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, hydatid cyst, calculi (stones) and tumours.[10][11]

Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles, although rare, constitutes the most common neoplasm of the seminal vesicles; even rarer neoplasms include sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, neuroendocrine carcinoma, paraganglioma, epithelial stromal tumors and lymphoma.[12]

Inflammation

Seminal vesiculitis (also known as spermatocystitis) is an inflammation of the seminal vesicles, most often caused by bacterial infection. Symptoms of seminal vesiculitis can include vague back or lower abdominal pain; penile, scrotal, or perineal pain; painful ejaculation; hematospermia; irritative and obstructive voiding symptoms; and impotence.[13]

It is usually treated by administration of antibiotics. In intractable cases, in case of patient discomfort, transurethral seminal vesiculoscopy may be considered.[14][15]

Additional images

Seminal vesicles seen on axial MRI scan

Seminal vesicles seen on axial MRI scan Human male reproductive system.

Human male reproductive system. Seminal vesicles

Seminal vesicles Coronal section of pelvis, showing arrangement of fasciae. Viewed from behind.

Coronal section of pelvis, showing arrangement of fasciae. Viewed from behind. Male pelvic organs seen from right side.

Male pelvic organs seen from right side. Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculae seminales.

Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculae seminales. Vesiculae seminales and ampullae of ductus deferentes, seen from the front.

Vesiculae seminales and ampullae of ductus deferentes, seen from the front. Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra.

Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra.- Cross section of seminal vesicle through a microscope.

See also

References

- ↑ Rowen D. Frandson; W. Lee Wilke; Anna Dee Fails (2009). "Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System". Anatomy and Physiology of Farm Animals (7th ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 409. ISBN 0-8138-1394-8. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- 1 2 Michael H. Ross; Wojciech Pawlina (2010). "Male Reproductive System". Histology: A Text and Atlas, with Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology (6th ed.). p. 828. ISBN 978-0781772006.

- ↑ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Adam, W.M. Mitchell (2005). Gray's Anatomy for Students. illustrations by Richard Tibbitts and Paul Richardson. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 407–409. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Gary C. Schoenwolf; Steven B. Bleyl; Philip R. Brauer; Philippa H. Francis-West (November 2014). "Chapter 16: Development of the Reproductive System". Larsen's Human Embryology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 9781455706846.

- 1 2 Barbara Young; James S. Lowe; Alan Stevens; John W. Heath; Philip J. Deakin (2006). Wheater's Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Atlas. drawings by Philip J. (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- ↑ Kierszenbaum, Abraham L.; Tres, Laura (2011). "Chapter 21: Sperm Transport and Maturation". Histology and Cell Biology: An Introduction to Pathology (3rd ed.). St. Louis [u.a.]: Mosby. p. 624. ISBN 978-0323078429.

- ↑ Charles Huggins; William W. Scott; J. Henry Heinen (1 May 1942). "Chemical composition of human semen and of the secretions of the prostate and seminal vesicles". American Journal of Physiology. American Physiological Society. 136 (3): 467–473. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ↑ B. Fey; F. Heni; A. Kuntz; D. F. McDonald; L. Quenu; L. G. jr. Wesson; C. Wilson (6 December 2012). Physiologie und Pathologische Physiologie / Physiology and Pathological Physiology / Physiologie Normale et Pathologique. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 611–. ISBN 978-3-642-46018-0.

- 1 2 3 Gonzales GF (2001). "Function of seminal vesicles and their role on male fertility". Asian J. Androl. 3 (4): 251–8. PMID 11753468.

- 1 2 El-Hakim, Assaad (13 November 2006). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Disorders of the Ejaculatory Ducts and Seminal Vesicles". In Smith, Arthur D. Smith's Textbook of Endourology (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 759–766. ISBN 978-1550093650.

- ↑ "Seminal vesicle diseases". Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

- ↑ Katafigiotis, Ioannis; Sfoungaristos, Stavros; Duvdevani, Mordechai; Mitsos, Panagiotis; Roumelioti, Eleni; Stravodimos, Konstantinos; Anastasiou, Ioannis; Constantinides, Constantinos A. (31 March 2016). "Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles. A review of the literature" (PDF). Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia: Organo Ufficiale [di] Società Italiana Di Ecografia Urologica E Nefrologica / Associazione Ricerche in Urologia. 88 (1): 47–51. doi:10.4081/aiua.2016.1.47. ISSN 1124-3562. PMID 27072175.

- ↑ Zeitlin, S. I.; Bennett, C. J. (1 November 1999). "Chapter 25: Seminal vesiculitis". In Curtis Nickel, J. Textbook of Prostatitis. CRC Press. pp. 219–225. ISBN 9781901865042.

- ↑ La Vignera S (October 2011). "Male accessory gland infection and sperm parameters". International Journal of Andrology. 42 (34): e330–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01200.x. PMID 21696400.

- ↑ Bianjiang Liu; Jie Li; Pengchao Li; Jiexiu Zhang; Ninghong Song; Zengjun Wang; Changjun Yin (February 2014). "Transurethral seminal vesiculoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of intractable seminal vesiculitis". The Journal of International Medical Research. 42 (1): 236–42. doi:10.1177/0300060513509472. PMID 24391141.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Seminal vesicle. |

- Histology image: 17501loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Male Reproductive System: prostate, seminal vesicle"

- Anatomy photo:44:04-0202 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: The Urinary Bladder"

- Anatomy photo:44:08-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: Structures Located Posterior to the Urinary Bladder"