Scale of temperature

Scale of temperature is a way to measure temperature quantitatively.

Formal description

According to the zeroth law of thermodynamics, being in thermal equilibrium is an equivalence relation. Thus all thermal systems may be divided into a quotient set by this equivalence relation, denoted below as M. Assume the set M has the cardinality of c, then one can construct an injective function ƒ: M → R , by which every thermal system will have a number associated with it such that when and only when two thermal systems have the same such value, they will be in thermal equilibrium. This is clearly the property of temperature, and the specific way of assigning numerical values as temperature is called a scale of temperature.[1][2][3] In practical terms, a temperature scale is always based on usually a single physical property of a simple thermodynamic system, called a thermometer, that defines a scaling function mapping the temperature to the measurable thermometric parameter. Such temperature scales that are purely based on measurement are called empirical temperature scales.

The second law of thermodynamics provides a fundamental, natural definition of thermodynamic temperature starting with a null point of absolute zero. A scale for thermodynamic temperature is established similarly to the empirical temperature scales, however, needing only one additional fixing point.

Empirical scales

Empirical scales are based on the measurement of physical parameters that express the property of interest to be measured through some formal, most commonly a simple linear, functional relationship. For the measurement of temperature, the formal definition of thermal equilibrium in terms of the thermodynamic coordinate spaces of thermodynamic systems, expressed in the zeroth law of thermodynamics, provides the framework to measure temperature.

All temperature scales, including the modern thermodynamic temperature scale used in the International System of Units, are calibrated according to thermal properties of a particular substance or device. Typically, this is established by fixing two well-defined temperature points and defining temperature increments via a linear function of the response of the thermometric device. For example, both the old Celsius scale and Fahrenheit scale were originally based on the linear expansion of a narrow mercury column within a limited range of temperature,[4] each using different reference points and scale increments.

Different empirical scales may not be compatible with each other, except for small regions of temperature overlap. If an alcohol thermometer and a mercury thermometer have same two fixed points, namely the freezing and boiling point of water, their reading will not agree with each other except at the fixed points, as the linear 1:1 relationship of expansion between any two thermometric substances may not be guaranteed.

Empirical temperature scales are not reflective of the fundamental, microscopic laws of matter. Temperature is a universal attribute of matter, yet empirical scales map a narrow range onto a scale that is known to have a useful functional form for a particular application. Thus, their range is limited. The working material only exists in a form under certain circumstances, beyond which it no longer can serve as a scale. For example, mercury freezes below 234.32 K, so temperature lower than that cannot be measured in a scale based on mercury. Even ITS-90, which interpolates among different ranges of temperature, has only a range of 0.65 K to approximately 1358 K (−272.5 °C to 1085 °C).

Ideal gas scale

When pressure approaches zero, all real gas will behave like ideal gas, that is, pV of a mole of gas relying only on temperature. Therefore, we can design a scale with pV as its argument. Of course any bijective function will do, but for convenience's sake linear function is the best. Therefore, we define it as [5]

The ideal gas scale is in some sense a "mixed" scale. It relies on the universal properties of gas, a big advance from just a particular substance. But still it is empirical since it puts gas at a special position and thus has limited applicability—at some point no gas can exist. One distinguishing characteristic of ideal gas scale, however, is that it precisely equals thermodynamical scale when it is well defined (see below).

International temperature scale of 1990

ITS-90 is designed to represent the thermodynamic temperature scale (referencing absolute zero) as closely as possible throughout its range. Many different thermometer designs are required to cover the entire range. These include helium vapor pressure thermometers, helium gas thermometers, standard platinum resistance thermometers (known as SPRTs, PRTs or Platinum RTDs) and monochromatic radiation thermometers.

Although the Kelvin and Celsius scales are defined using absolute zero (0 K) and the triple point of water (273.16 K and 0.01 °C), it is impractical to use this definition at temperatures that are very different from the triple point of water. Accordingly, ITS–90 uses numerous defined points, all of which are based on various thermodynamic equilibrium states of fourteen pure chemical elements and one compound (water). Most of the defined points are based on a phase transition; specifically the melting/freezing point of a pure chemical element. However, the deepest cryogenic points are based exclusively on the vapor pressure/temperature relationship of helium and its isotopes whereas the remainder of its cold points (those less than room temperature) are based on triple points. Examples of other defining points are the triple point of hydrogen (−259.3467 °C) and the freezing point of aluminum (660.323 °C).

Thermometers calibrated per ITS–90 use complex mathematical formulas to interpolate between its defined points. ITS–90 specifies rigorous control over variables to ensure reproducibility from lab to lab. For instance, the small effect that atmospheric pressure has upon the various melting points is compensated for (an effect that typically amounts to no more than half a millikelvin across the different altitudes and barometric pressures likely to be encountered). The standard even compensates for the pressure effect due to how deeply the temperature probe is immersed into the sample. ITS–90 also draws a distinction between "freezing" and "melting" points. The distinction depends on whether heat is going into (melting) or out of (freezing) the sample when the measurement is made. Only gallium is measured while melting, all the other metals are measured while the samples are freezing.

There are often small differences between measurements calibrated per ITS–90 and thermodynamic temperature. For instance, precise measurements show that the boiling point of VSMOW water under one standard atmosphere of pressure is actually 373.1339 K (99.9839 °C) when adhering strictly to the two-point definition of thermodynamic temperature. When calibrated to ITS–90, where one must interpolate between the defining points of gallium and indium, the boiling point of VSMOW water is about 10 mK less, about 99.974 °C. The virtue of ITS–90 is that another lab in another part of the world will measure the very same temperature with ease due to the advantages of a comprehensive international calibration standard featuring many conveniently spaced, reproducible, defining points spanning a wide range of temperatures.

Celsius scale

Celsius (known until 1948 as centigrade) is a temperature scale that is named after the Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius (1701–1744), who developed a similar temperature scale two years before his death. The degree Celsius (°C) can refer to a specific temperature on the Celsius scale as well as a unit to indicate a temperature interval (a difference between two temperatures or an uncertainty).

From 1744 until 1954, 0 °C was defined as the freezing point of water and 100 °C was defined as the boiling point of water, both at a pressure of one standard atmosphere. Although these defining correlations are commonly taught in schools today, by international agreement the unit "degree Celsius" and the Celsius scale are currently defined by two different points: absolute zero, and the triple point of VSMOW (specially prepared water). This definition also precisely relates the Celsius scale to the Kelvin scale, which defines the SI base unit of thermodynamic temperature (symbol: K). Absolute zero, the hypothetical but unattainable temperature at which matter exhibits zero entropy, is defined as being precisely 0 K and −273.15 °C. The temperature value of the triple point of water is defined as being precisely 273.16 K and 0.01 °C.[6]

This definition fixes the magnitude of both the degree Celsius and the kelvin as precisely 1 part in 273.16 parts, the difference between absolute zero and the triple point of water. Thus, it sets the magnitude of one degree Celsius and that of one kelvin as exactly the same. Additionally, it establishes the difference between the two scales' null points as being precisely 273.15 degrees Celsius (−273.15 °C = 0 K and 0 °C = 273.15 K).[7]

Thermodynamic scale

Thermodynamic scale differs from empirical scales in that it is absolute. It is based on the fundamental laws of thermodynamics or statistical mechanics instead of some arbitrary chosen working material. Besides it covers full range of temperature and has simple relation with microscopic quantities like the average kinetic energy of particles (see equipartition theorem). In experiments ITS-90 is used to approximate thermodynamic scale due to simpler realization.

Definition

Lord Kelvin devised the thermodynamic scale based on the efficiency of heat engines as shown below:

The efficiency of an engine is the work divided by the heat introduced to the system or

- ,

where wcy is the work done per cycle. Thus, the efficiency depends only on qC/qH.

Because of Carnot theorem, any reversible heat engine operating between temperatures T1 and T2 must have the same efficiency, meaning, the efficiency is the function of the temperatures only:

In addition, a reversible heat engine operating between temperatures T1 and T3 must have the same efficiency as one consisting of two cycles, one between T1 and another (intermediate) temperature T2, and the second between T2 and T3. This can only be the case if

Specializing to the case that is a fixed reference temperature: the temperature of the triple point of water. Then for any T2 and T3,

Therefore, if thermodynamic temperature is defined by

then the function f, viewed as a function of thermodynamic temperature, is

and the reference temperature T1 has the value 273.16. (Of course any reference temperature and any positive numerical value could be used—the choice here corresponds to the Kelvin scale.)

Equality to ideal gas scale

It follows immediately that

Substituting Equation 3 back into Equation 1 gives a relationship for the efficiency in terms of temperature:

This is identical to the efficiency formula for Carnot cycle, which effectively employs the ideal gas scale. This means that the two scales equal numerically at every point.

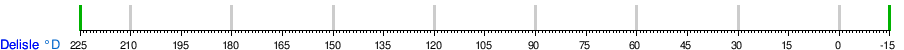

Conversion table between the different temperature units

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ H A Buchdahl. "2.Zeroth law". The concepts of classical thermodynamics. Cambridge U.P.1966. ISBN 978-0-521-04359-5.

- ↑ Giuseppe Morandi; F Napoli; E Ercolessi. Statistical mechanics : an intermediate course. Singapore ; River Edge, N.J. : World Scientific, ©2001. pp. 6~7. ISBN 978-981-02-4477-4.

- ↑ Walter Greiner; Ludwig Neise; Horst Stöcker. Thermodynamics and statistical mechanics. New York [u.a.] : Springer, 2004. pp. 6~7.

- ↑ Carl S. Helrich (2009). Modern Thermodynamics with Statistical Mechanics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-540-85417-3.

- ↑ "Thermometers and the Ideal Gas Temperature Scale".

- ↑ "SI brochure, section 2.1.1.5". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- ↑ "Essentials of the SI: Base & derived units". Retrieved 9 May 2008.