Samaritans

|

Samaritans on Mount Gerizim during Sukkot | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 777 (2015) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Samaritan Community Populations | |

| Holon, Israel | 400[1] |

| Kiryat Luza, West Bank, joint Israeli and Palestinian control.[2] | 350[1] |

| Other Israeli cities | ≈50 |

| Religions | |

| Samaritanism | |

| Scriptures | |

| Samaritan Book of Joshua[3] | |

| Languages | |

|

Modern vernacular Hebrew, Arabic Past vernacular Arabic, preceded by Aramaic and earlier Hebrew Liturgical Samaritan Hebrew, Samaritan Aramaic, Samaritan Arabic[3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Jews, other Levantines, Assyrians | |

The Samaritans (Samaritan Hebrew: שוֹמְרִים Samerim "Guardians/Keepers/Watchers [of the Law/Torah]", Hebrew: שומרונים Shomronim, Arabic: السامريون Samāriyyūn) are an ethnoreligious group of the Levant originating from the Israelites (Hebrews) of the Ancient Near East.

Ancestrally, Samaritans claim descent from the tribe of Ephraim and tribe of Manasseh (two sons of Joseph) as well as from the Levites,[1] who have links to ancient Samaria from the period of their entry into Canaan, while some suggest that it was from the beginning of the Babylonian captivity up to the Samaritan polity under the rule of Baba Rabba. Samaritans used to include descendants who ascribe to the Benjamin tribe, but the line became extinct in the mid-20th century.[4] The split between them and the Judeans began during the time of Eli when, according to Samaritan tradition, Judeans split off from the central Israelite tradition.[5]

In the Talmud, a central post-exilic religious text of Judaism, the Samaritans are called Cutheans (Hebrew: כותים, Kutim), referring to the ancient city of Kutha, geographically located in what is today Iraq.[6] In the biblical account, however, Cuthah was one of several cities from which people were brought to Samaria,[7] and they worshiped Nergal.[8][9] Modern genetics partially supports both the claims of the Samaritans and the account in the Talmud, suggesting that the genealogy of the Samaritans lies in some combination of these two accounts.[10] Genetically, modern Samaritan populations are found to have "much greater affinity" genetically to Jews than to neighbouring Palestinian Arabs.[11] This suggests that the Samaritans remained a genetically isolated population.[11]

The Samaritans are adherents of Samaritanism, a religion closely related to rabbinical Judaism. Samaritans believe that their worship, which is based on the Samaritan Pentateuch,[12] is the true religion of the ancient Israelites from before the Babylonian captivity, preserved by those who remained in the Land of Israel, as opposed to rabbinical Judaism, which they see as a related but altered and amended religion, brought back by those returning from the Babylonian captivity. The Samaritans believe that Mount Gerizim was the original Holy Place of Israel from the time that Joshua conquered Israel. The major issue between Rabbinical Jews (Jews who follow post-exile rabbinical interpretations of Judaism, who are the vast majority of Jews today) and Samaritans has always been the location of the chosen place to worship God; Jerusalem according to the Jewish faith or Mount Gerizim according to the Samaritan faith.[5]

Once a large community, the Samaritan population appears to have shrunk significantly in the wake of the bloody suppression of the Samaritan Revolts (mainly in 529 CE and 555 CE) against the Byzantine Empire. Conversion to Christianity under the Byzantines also restricted their numbers. Conversions to Islam are also thought to have taken place,[13][14] and by the early Middle Ages Benjamin of Tudela estimated only around 1,900 Samaritans remained in Palestine and Syria.[15] As of January 1, 2015, the population was 777, divided between Kiryat Luza on Mount Gerizim and the city of Holon, just outside Tel Aviv.[16][17] Most Samaritans in Israel and the West Bank today speak Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic. For liturgical purposes, Samaritan Hebrew, Samaritan Aramaic, and Arabic are used, all written with the Samaritan alphabet, a variant of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, which is distinct from the Hebrew alphabet.[18] Hebrew and later Aramaic were languages in use by the Jewish and Samaritan inhabitants of Judea prior to the Roman exile.[19]

Samaritans have a standalone religious status in Israel and there are occasional conversions from Judaism to Samaritanism and vice-versa due to marriages. While some Rabbinic authorities consider Samaritanism to be a branch of Judaism,[20] the Chief Rabbinate of Israel requires Samaritans to officially go through a formal conversion to Judaism in order to be recognized as Halakhic Jews. One example is Israeli TV personality Sofi Tsedaka, who formally converted to rabbinical Judaism at the age of 18.[21][22] Samaritans with Israeli citizenship are obligated with mandatory service in the Israel Defense Forces, while those with double Israeli-Palestinian citizenship (living in Kiryat Luza) are generally excluded.

Etymology

There is conflict over the etymology of the name for the Samaritans in Hebrew, stemming from the fact that they are referred to differently in different dialects of Hebrew. This has accompanied controversy over whether the Samaritans are named after the geographic area of Samaria (in the northern West Bank), or whether the area received its name from the group. This distinction is controversial in part because different interpretations can be used to justify or deny claims of ancestry over this region, which has been deeply contested in modern times.

In Samaritan Hebrew the Samaritans call themselves "Samerim", which according to the Anchor Bible Dictionary, is derived from the Ancient Hebrew term Šamerim/Samerim שַמֶרִים, meaning "Guardians/Keepers/Watchers [of the Law/Torah]".[23]

Biblical Hebrew Šomerim[24] (Arabic: سامرين)[25]) "Guardians" (singular Šomer) comes from the Hebrew Semitic root שמר, which means "to watch, guard".[26]

Historically, Samaria was the key geographical concentration of the Samaritan community. Thus, it may suggest the region of Samaria is named after the Samaritans, rather than the Samaritans being named after the region. In Jewish tradition, however, it is sometimes claimed that Mount Samaria, meaning "Watch Mountain", is actually named so because watchers used to watch from those mountains for approaching armies from Egypt in ancient times. In Modern Hebrew, the Samaritans are called Shomronim, which would appear to simply mean "inhabitants of Samaria". This is a politically sensitive distinction.

That the etymology of the Samaritans' ethnonym in Samaritan Hebrew is derived from "Guardians/Keepers/Watchers [of the Law/Torah]", as opposed to Samaritans being named after the region of Samaria, has in history been supported by a number of Christian Church fathers, including Epiphanius of Salamis in the Panarion, Jerome and Eusebius in the Chronicon and Origen in The Commentary on Saint John's Gospel, and in some Talmudic commentary of Tanhuma on Genesis 31, and Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer 38, p. 21.[27][28][29][30][31][32]

History and origin

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

| The Tribes |

| Related topics |

Samaritan sources

According to Samaritan tradition, Mount Gerizim was the original Holy Place of the Israelites from the time that Joshua conquered Canaan and the tribes of Israel settled the land. The reference to Mount Gerizim derives from the biblical story of Moses ordering Joshua to take the Twelve Tribes of Israel, to the mountains by Nablus and place half of the tribes, six in number, on the top of Mount Gerizim, the Mount of the Blessing, and the other half in Mount Ebal, the Mount of the Curse. The two mountains were used to symbolize the significance of the commandments and serve as a warning to whoever disobeyed them (Deut. 11:29; 27:12; Josh. 8:33).

Samaritans claim they are Israelite descendants of the Northern Israelite tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, who survived the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) by the Assyrians in 722 BCE.

Samaritan historiography places the basic schism from the remaining part of Israel after the tribes of Israel conquered and returned to the land of Canaan, led by Joshua. After Joshua's death, Eli the priest left the tabernacle which Moses erected in the desert and established on Mount Gerizim, and built another one under his own rule in the hills of Shiloh.

Abu l-Fath, who in the 14th century wrote a major work of Samaritan history, comments on Samaritan origins as follows:[33]

A terrible civil war broke out between Eli son of Yafni, of the line of Ithamar, and the sons of Pincus (Phinehas), because Eli son of Yafni resolved to usurp the High Priesthood from the descendants of Pincus. He used to offer sacrifices on an altar of stones. He was 50 years old, endowed with wealth and in charge of the treasury of the children of Israel. ...He offered a sacrifice on the altar, but without salt, as if he were inattentive. When the Great High Priest Ozzi learned of this, and found the sacrifice was not accepted, he thoroughly disowned him; and it is (even) said that he rebuked him.

Thereupon he and the group that sympathized with him, rose in revolt and at once he and his followers and his beasts set off for Shiloh. Thus Israel split in factions. He sent to their leaders saying to them, Anyone who would like to see wonderful things, let him come to me. Then he assembled a large group around him in Shiloh, and built a Temple for himself there; he constructed a place like the Temple (on Mount Gerizim). He built an altar, omitting no detail—it all corresponded to the original, piece by piece.

At this time the Children of Israel split into three factions. A loyal faction on Mount Gerizim; a heretical faction that followed false gods; and the faction that followed Eli son of Yafni on Shiloh.

Further, the Samaritan Chronicle Adler, or New Chronicle, believed to have been composed in the 18th century using earlier chronicles as sources states:

And the children of Israel in his days divided into three groups. One did according to the abominations of the Gentiles and served other gods; another followed Eli the son of Yafni, although many of them turned away from him after he had revealed his intentions; and a third remained with the High Priest Uzzi ben Bukki, the chosen place.

Jewish sources

The emergence of the Samaritans as an ethnic and religious community distinct from other Levant peoples appears to have occurred at some point after the Assyrian conquest of the Israelite Kingdom of Israel in approximately 721 BCE. The records of Sargon II of Assyria indicate that he deported 27,290 inhabitants of the former kingdom.

Jewish tradition affirms the Assyrian deportations and replacement of the previous inhabitants by forced resettlement by other peoples, but claims a different ethnic origin for the Samaritans. The Talmud accounts for a people called "Cuthim" on a number of occasions, mentioning their arrival by the hands of the Assyrians. According to 2 Kings[34] and Josephus[35] the people of Israel were removed by the king of the Assyrians (Sargon II)[36] to Halah, to Gozan on the Khabur River and to the towns of the Medes. The king of the Assyrians then brought people from Babylon, Cuthah, Avah, Emath, and Sepharvaim to place in Samaria. Because God sent lions among them to kill them, the king of the Assyrians sent one of the priests from Bethel to teach the new settlers about God's ordinances. The eventual result was that the new settlers worshipped both the God of the land and their own gods from the countries from which they came.

This account is contradicted by the version in Chronicles,[37] where, following Samaria's destruction, King Hezekiah is depicted as endeavouring to draw the Ephraimites and Manassites closer to Judah. Temple repairs at the time of Josiah were financed by money from all "the remnant of Israel" in Samaria, including from Manasseh, Ephraim and Benjamin.[38] Jeremiah likewise speaks of people from Shechem, Shiloh and Samaria who brought offerings of frankincense and grain to the house of the Lord.[39] Chronicles makes no mention of an Assyrian resettlement.[40] Yitzakh Magen argues that the version of Chronicles is perhaps closer to the historical truth, and that the Assyrian settlement was unsuccessful, a notable Israelite population remained in Samaria, part of which, following the conquest of Judah, fled south and settled there as refugees.[41]

A Midrash (Genesis Rabbah Sect. 94) relates about an encounter between Rabbi Meir and a Samaritan. The story that developed includes the following dialogue:

- Rabbi Meir: What tribe are you from?

- The Samaritan: From Joseph.

- Rabbi Meir: No!

- The Samaritan: From which one then?

- Rabbi Meir: From Issachar.

- The Samaritan: How do you figure?

- Rabbi Meir: For it is written (Gen 46:13): The sons of Issachar: Tola, Puvah, Iob, and Shimron. These are the Samaritans (shamray).

Zertal dates the Assyrian onslaught at 721 BCE to 647 BCE and discusses three waves of imported settlers. He shows that Mesopotamian pottery in Samaritan territory cluster around the lands of Menasheh and that the type of pottery found was produced around 689 BCE. Some date their split with the Jews to the time of Nehemiah, Ezra, and the building of the Second Temple in Jerusalem after the Babylonian exile. Returning exiles considered the Samaritans to be non-Israelites and, thus, not fit for this religious work.

The Encyclopaedia Judaica (under "Samaritans") summarizes both past and the present views on the Samaritans' origins. It says:

Until the middle of the 20th century it was customary to believe that the Samaritans originated from a mixture of the people living in Samaria and other peoples at the time of the conquest of Samaria by Assyria (722–721 BCE). The Biblical account in II Kings 17 had long been the decisive source for the formulation of historical accounts of Samaritan origins. Reconsideration of this passage, however, has led to more attention being paid to the Chronicles of the Samaritans themselves. With the publication of Chronicle II (Sefer ha-Yamim), the fullest Samaritan version of their own history became available: the chronicles, and a variety of non-Samaritan materials.According to the former, the Samaritans are the direct descendants of the Joseph tribes, Ephraim and Manasseh, and until the 17th century CE they possessed a high priesthood descending directly from Aaron through Eleazar and Phinehas. They claim to have continuously occupied their ancient territory and to have been at peace with other Israelite tribes until the time when Eli disrupted the Northern cult by moving from Shechem to Shiloh and attracting some northern Israelites to his new followers there. For the Samaritans, this was the 'schism' par excellence.("Samaritans" in Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1972, Volume 14, op. cit., col. 727.)

Furthermore, to this day the Samaritans claim descent from the tribe of Joseph:

The laymen also possess their traditional claims. They are all of the tribe of Joseph, except those of the tribe of Benjamin, but this traditional branch of people, which, the Chronicles assert, was established at Gaza in earlier days, seems to have disappeared. There exists an aristocratic feeling amongst the different families in this community, and some are very proud over their pedigree and the great men it had produced.(J. A. Montgomery, The Samaritans The Earliest Jewish Sect: Their History, Theology And Literature, 1907, op. cit., p. 32.)

Dead Sea scrolls

The Dead Sea scroll 4Q372 hopes that the northern tribes will return to the land of Joseph. The current dwellers in the north are referred to as fools, an enemy people. However they are not referred to as foreigners. It goes on to say that the Samaritans mocked Jerusalem and built a temple on a high place to provoke Israel.[42]

Tensions between the Samaritans and the Judeans

The narratives in Genesis about the rivalries among the twelve sons of Jacob describe tensions between north and south. They were temporarily united in the United Monarchy, but after the death of Solomon the kingdom split in two, the Kingdom of Israel with its capital Samaria and the Kingdom of Judah with its capital Jerusalem.

The Deuteronomistic history, written in Judah, portrayed Israel as a sinful kingdom, divinely punished for its idolatry and iniquity by being destroyed by the Assyrians in 720 BCE.

The tensions continued in the postexilic period. Chronicles is more inclusive than Ezra–Nehemiah since for the Chronicler the ideal is of one Israel with twelve tribes; the Chronicler concentrates on Judah and ignores northern Israel.[43]

The Samaritans claimed that they were the true Israel who were descendants of the "Ten Lost Tribes" taken into Assyrian captivity. They had their own temple on Mount Gerizim and claimed that it was the original sanctuary. Moreover, they claimed that their version of the Pentateuch was the original and that the Jews had a falsified text produced by Ezra during the Babylonian exile.

Both Jewish and Samaritan religious leaders taught that it was wrong to have any contact with the opposite group, and neither was to enter each other's territories or even to speak to one another. During the New Testament period, although the tensions went unrecognized by Roman authorities, Josephus reports numerous violent confrontations between Jews and Samaritans throughout the first half of the first century.[44]

Rejection by Judeans

According to the Jewish version of events, when the Judean exile ended in 538 BCE and the exiles began returning home from Babylon, they found their former homeland populated by other people who claimed the land as their own and Jerusalem, their former glorious capital, in ruins. The inhabitants worshiped the Pagan gods, but when the then-sparsely populated areas became infested with dangerous wild beasts, they appealed to the king of Assyria for Israelite priests to instruct them on how to worship the "God of that country." The result was a syncretistic religion, in which national groups worshiped the Hebrew God, but they also served their own gods in accordance with the customs of the nations from which they had been brought.

According to 2 Chronicles 36:22–23, the Persian emperor, Cyrus the Great (reigned 559–530 BCE), permitted the return of the exiles to their homeland and ordered the rebuilding of the Temple (Zion). The prophet Isaiah identified Cyrus as "the Lord's Messiah" (see Isaiah 45:1). The word "Messiah" refers to an anointed one, such as a king or priest.

Ezra 4 says that the local inhabitants of the land offered to assist with the building of the new temple during the time of Zerubbabel, but their offer was rejected. According to Ezra, this rejection precipitated a further interference not only with the rebuilding of the temple but also with the reconstruction of Jerusalem.

The text is not clear on this matter, but one possibility is that these "people of the land" were thought of as Samaritans. We do know that Samaritan and Jewish alienation increased, and that the Samaritans eventually built their own temple on Mount Gerizim, near Shechem.

The rebuilding of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem took several decades. The project was first led by Sheshbazzar (ca. 538 BCE), later by Zerubbabel and Jeshua, and later still by Haggai and Zechariah (520–515 BCE). The work was completed in 515 BCE.

The term "Cuthim" applied by Jews to the Samaritans had clear pejorative connotations, implying that they were interlopers brought in from Kutha in Mesopotamia and rejecting their claim of descent from the ancient Tribes of Israel.

Assyrian account of the conquest and settlement of Samaria

However, the following account of the Assyrian kings, which was among the archaeological discoveries in Babylon, differs from the Samaritan account, and confirms much of the Jewish biblical account but may differ in regard to the ethnicity of the foreigners settled in Samaria by Assyria. At one point it is simply said that they were from Arabia, while at another, that they were brought from a number of countries conquered by Sargon II:

[the Samar]ians [who had agreed with a hostile king] ... I fought with them and decisively defeated them] ... carried off as spoil. 50 chariots for my royal force ... [the rest of them I settled in the midst of Assyria]. ... The Tamudi, Ibadidi, Marsimani and Hayappa, who live in distant Arabia, in the desert, who knew neither overseer nor commander, who never brought tribute to any king--with the help of Ashshur my lord, I defeated them. I deported the rest of them. I settled them in Samaria/Samerina. (Sargon II Inscriptions, COS 2.118A, p. 293

Also,

The inhabitants of Samaria/Samerina, who agreed [and plotted] with a king [hostile to] me, not to do service and not to bring tribute [to Ashshur] and who did battle, I fought against them with the power of the great gods, my lords. I counted as spoil 27,280 people, together with their chariots, and gods, in which they trusted. I formed a unit with 200 of [their] chariots for my royal force. I settled the rest of them in the midst of Assyria. I repopulated Samaria/Samerina more than before. I brought into it people from countries conquered by my hands. I appointed my eunuch as governor over them. And I counted them as Assyrians. (Nimrud Prisms, COS 2.118D, pp. 295-296)[45]

Further history

Temple on Mount Gerizim

Archaeological excavations at Mount Gerizim indicate that a Samaritan temple was built there in the first half of the 5th century BC.[46] The date of the schism between Samaritans and Jews is unknown, but by the early 4th century BCE the communities seem to have had distinctive practices and communal separation.

According to Samaritans,[47] it was on Mount Gerizim that Abraham was commanded by God to offer Isaac, his son, as a sacrifice Genesis 22:2. In both narratives, God then causes the sacrifice to be interrupted, explaining that this was the ultimate test of Abraham's obedience, as a result of which all the world would receive blessing.

The Torah mentions the place where God shall choose to establish His name (Deut 12:5), and Judaism takes this to refer to Jerusalem. However, the Samaritan text speaks of the place where God has chosen to establish His name, and Samaritans identify it as Mount Gerizim, making it the focus of their spiritual values.

The legitimacy of the Samaritan temple was attacked by Jewish scholars including Andronicus ben Meshullam.

In the Christian Bible, the Gospel of John relates an encounter between a Samaritan woman and Jesus in which she says that the mountain was the center of their worship John 4:20.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes and Hellenization

In the 2nd century BCE a series of events led to a revolution of some Judeans against Antiochus IV.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes was on the throne of the Seleucid Empire from 175 to 163 BCE. His policy was to Hellenize his entire kingdom and standardize religious observance. According to 1 Maccabees 1:41-50 he proclaimed himself the incarnation of the Greek god Zeus and mandated death to anyone who refused to worship him.

The universal peril led the Samaritans, eager for safety, to repudiate all connection and kinship with the Jews. The request was granted. This was put forth as the final breach between the two groups, being alleged at a much later date in the Christian Bible (John 4:9), "For Jews have no dealings with Samaritans"[48]—or not "alleged" if the Greek sunchrasthai merely refers to not sharing utensils (NABRE).

Anderson notes that during the reign of Antiochus IV (175–164 BCE):[49]

the Samaritan temple was renamed either Zeus Hellenios (willingly by the Samaritans according to Josephus) or, more likely, Zeus Xenios, (unwillingly in accord with 2 Macc. 6:2) Bromiley, 4.304).

Josephus Book 12, Chapter 5 quotes the Samaritans as saying:

We therefore beseech thee, our benefactor and saviour, to give order to Apolonius, the governor of this part of the country, and to Nicanor, the procurator of thy affairs, to give us no disturbances, nor to lay to our charge what the Jews are accused for, since we are aliens from their nation and from their customs, but let our temple which at present hath no name at all, be named the Temple of Jupiter Hellenius.

Shortly afterwards, the Greek king sent Gerontes the Athenian to force the Jews of Israel to violate their ancestral customs and live no longer by the laws of God; and to profane the Temple in Jerusalem and dedicate it to Olympian Zeus, and the one on Mount Gerizim to Zeus, Patron of Strangers, as the inhabitants of the latter place had requested. —II Maccabees 6:1–2

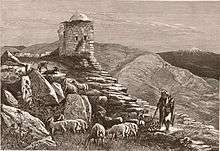

This Samaritan Temple at Mount Gerizim was destroyed by John Hyrcanus in about 128 BC, having existed about 200 years. Only a few stone remnants of it exist today.[50]

164 BCE and after

During the Hellenistic period, Samaria was largely divided between a Hellenizing faction based in Samaria (Sebastaea) and a pious faction, led by the High Priest and based largely around Shechem and the rural areas. Samaria was a largely autonomous state nominally dependent on the Seleucid Empire until around 129 BCE, when the Jewish Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus destroyed the Samaritan temple and devastated Samaria.

Roman period

Under the Roman Empire, Samaria was a part of the province of Judaea.

Samaritans appear briefly in the Christian gospels, most notably in the account of the Samaritan woman at the well and the parable of the Good Samaritan. In the latter it is only the Samaritan who helped the man stripped of clothing, beaten, and left on the road half dead, his Abrahamic covenantal circumcision implicitly evident. The priest and Levite walked past. But the Samaritan helped the naked man regardless of his nakedness (itself religiously offensive to the priest and Levite), his self-evident poverty, or to which Hebrew sect he belonged (which was unclear to any, due to his nakedness).

This period is considered as something of a golden age for the Samaritan community, the population thought to number up to a million.[51] The Temple of Gerizim was rebuilt after the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Romans, around 135 CE. Much of Samaritan liturgy was set by the high priest Baba Rabba in the 4th century.[52]

A building dated to the second century BCE, the Delos Synagogue, is commonly identified as a Samaritan synagogue, which would make it the oldest known Jewish or Samaritan synagogue.[53] On the other hand, Matassa argues that, although there is evidence of Samaritans on Delos, there is no evidence the building was a synagogue.[54]

There were some Samaritans in the Sasanian Empire, where they served in the army.

Byzantine times

According to Samaritan sources, Eastern Roman emperor Zeno (who ruled 474-491 and whom the sources call "Zait the King of Edom") persecuted the Samaritans. The Emperor went to Neapolis (Shechem), gathered the elders and asked them to convert; when they refused, Zeno had many Samaritans killed, and re-built the synagogue to a church. Zeno then took for himself Mount Gerizim, where the Samaritans worshipped God, and built several edifices, among whom a tomb for his recently deceased son, on which he put a cross, so that the Samaritans, worshipping God, would prostrate in front of the tomb. Later, in 484, the Samaritans revolted. The rebels attacked Sichem, burnt five churches built on Samaritan holy places and cut the finger of bishop Terebinthus, who was officiating the ceremony of Pentecost. They elected a Justa (or Justasa/Justasus) as their king and moved to Caesarea, where a noteworthy Samaritan community lived. Here several Christians were killed and the church of St. Sebastian was destroyed. Justa celebrated the victory with games in the circus. According to John Malalas, the dux Palaestinae Asclepiades, whose troops were reinforced by the Caesarea-based Arcadiani of Rheges, defeated Justa, killed him and sent his head to Zeno.[55] According to Procopius, Terebinthus went to Zeno to ask for revenge; the Emperor personally went to Samaria to quell the rebellion.[56]

Modern historians believe that the order of the facts preserved by Samaritan sources should be inverted, as the persecution of Zeno was a consequence of the rebellion rather than its cause, and should have happened after 484, around 489. Zeno rebuilt the church of St. Procopius in Neapolis (Sichem) and the Samaritans were banned from Mount Gerizim, on whose top a signalling tower was built to alert in case of civil unrest.[57]

Under a charismatic, messianic figure named Julianus ben Sabar (or ben Sahir), the Samaritans launched a war to create their own independent state in 529. With the help of the Ghassanids, Emperor Justinian I crushed the revolt; tens of thousands of Samaritans died or were enslaved. The Samaritan faith was virtually outlawed thereafter by the Christian Byzantine Empire; from a population once at least in the hundreds of thousands, the Samaritan community dwindled to near extinction.

After the Muslim Conquests

Tens of thousands of Samaritans had died resisting the Byzantine Empire. Though guaranteed religious freedom after the Muslim conquest of Palestine, their numbers dropped further as a result of massacres and conversions.[58]

By the time of the early Muslim conquests, apart from Palestine, small dispersed communities of Samaritans were living also in Egypt, Syria, and Iran. Like other non-Muslims in the empire, such as Jews, Samaritans were considered to be People of the Book.

Their minority status was protected by the Muslim rulers, and they had the right to practice their religion, but, as dhimmi, adult males had to pay the jizya or "protection tax".

The tradition of men wearing a red tarboosh may go back to an order by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mutawakkil (847-861 BE) that required non-Muslims to be distinguished from Muslims.[59]

During the Crusades, Samaritans, like the non-Latin Christian inhabitants of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, were second-class citizens, but they were tolerated and perhaps favoured because they were docile and had been mentioned positively in the Christian New Testament.[60]

While the majority of the Samaritan population in Damascus was killed or converted during the reign of the Ottoman Pasha Mardam Beq in the early 17th century, the remainder of the Samaritan community there, in particular the Dinfi family, which is still influential today, moved back to Nablus in the 17th century.[61]

The Shechem community endured because most of the surviving diaspora returned, and they have maintained a tiny presence there to this day. In 1624, the last Samaritan High Priest of the line of Eleazar son of Aaron died without issue, but descendants of Aaron's other son, Ithamar, remained and took over the office.[62]

The situation of the Samaritan community improved significantly during the British Mandate of Palestine. At that time, they began to work in the public sector, like many other groups. The censuses of 1922 and 1931 recorded 163 and 182 Samaritans in Palestine, respectively.[63] The majority of them lived in Nablus.[63]

Samaritan origins of Palestinian Muslims in Nablus

Much of the local Palestinian population of Nablus is believed to be descended from Samaritans who converted to Islam.[62] According to the historian Fayyad Altif, large numbers of Samaritans converted due to persecution under various Muslim rulers, and because the monotheistic nature of Islam made it easy for them to accept it.[62] The Samaritans themselves describe the Ottoman period as the worst period in their modern history, as many Samaritan families were forced to convert to Islam during that time.[64] Even today, certain Nabulsi family names such as Maslamani, Yaish, and Shaksheer among others, are associated with Samaritan ancestry.[62]

For the Samaritans in particular, the passing of the al-Hakim Edict by the Fatimid Caliphate in 1021, under which all Jews and Christians in the Fatimid ruled southern Levant were ordered to either convert to Islam or leave, along with another notable forced conversion to Islam imposed at the hands of the rebel ibn Firāsa,[13][14] would contribute to their rapid unprecedented decrease, and ultimately almost complete extinction as a separate religious community. As a result, they have decreased from more than a million in late Roman (Byzantine) times to 150 people by the end of the Ottoman Era.

In 1940, the future Israeli president and historian Yitzhak Ben-Zvi wrote an article in which he stated that two thirds of the residents of Nablus and the surrounding neighboring villages are of Samaritan origin.[65] He mentioned the name of several Palestinian Muslim families as having Samaritan origins, including the Buwarda and Kasem families, who protected Samaritans from Muslim persecution in the 1850s.[65] He further claimed that these families had written records testifying to their Samaritan ancestry, which were maintained by their priests and elders.[65]

According to The Economist, "most ethnic Samaritans are now pious Muslims."[66]

Genetic studies

Demographic investigation

Demographic investigations of the Samaritan community were carried out in the 1960s. Detailed pedigrees of the last 13 generations show that the Samaritans comprise four lineages:

- The Tsedakah lineage, claiming descent from the tribe of Manasseh

- The Joshua-Marhiv lineage, claiming descent from the tribe of Ephraim

- The Danfi lineage, claiming descent from the tribe of Ephraim

- The priestly Cohen lineage from the tribe of Levi.

Y-DNA and mtDNA comparisons

Recently several genetic studies on the Samaritan population were made using haplogroup comparisons as well as wide-genome genetic studies. Of the 12 Samaritan males used in the analysis, 10 (83%) had Y chromosomes belonging to haplogroup J, which includes three of the four Samaritan families. The Joshua-Marhiv family belongs to Haplogroup J-M267 (formerly "J1"), while the Danfi and Tsedakah families belong to haplogroup J-M172 (formerly "J2"), and can be further distinguished by M67, the derived allele of which has been found in the Danfi family. The only Samaritan family not found in haplogroup J was the Cohen family (Tradition: Tribe of Levi) which was found haplogroup E-M78 (formerly "E3b1a M78").[67] This article predated the change of the classification of haplogroup E3b1-M78 to E3b1a-M78 and the further subdivision of E3b1a-M78 into 6 subclades based on the research of Cruciani, et al.[68]

The 2004 article on the genetic ancestry of the Samaritans by Shen et al. concluded from a sample comparing Samaritans to several Jewish populations, all currently living in Israel—representing the Beta Israel, Ashkenazi Jews, Iraqi Jews, Libyan Jews, Moroccan Jews, and Yemenite Jews, as well as Israeli Druze and Palestinians—that "the principal components analysis suggested a common ancestry of Samaritan and Jewish patrilineages. Most of the former may be traced back to a common ancestor in what is today identified as the paternally inherited Israelite high priesthood (Cohanim) with a common ancestor projected to the time of the Assyrian conquest of the kingdom of Israel."[10]

Archaeologists Aharoni, et al., estimated that this "exile of peoples to and from Israel under the Assyrians" took place during ca. 734–712 BCE.[69] The authors speculated that when the Assyrians conquered the northern kingdom of Israel, resulting in the exile of many of the Israelites, a subgroup of the Israelites that remained in the Land of Israel "married Assyrian and female exiles relocated from other conquered lands, which was a typical Assyrian policy to obliterate national identities."[10] The study goes on to say that "Such a scenario could explain why Samaritan Y chromosome lineages cluster tightly with Jewish Y lineages, while their mitochondrial lineages are closest to Iraqi Jewish and Israeli Arab mtDNA sequences." Non-Jewish Iraqis were not sampled in this study; however, mitochondrial lineages of Jewish communities tend to correlate with their non-Jewish host populations, unlike paternal lineages which almost always correspond to Israelite lineages.

Modern times

As of January 1, 2015, there were 777 Samaritans,[70] half of whom reside in their modern homes at Kiryat Luza on Mount Gerizim, which is sacred to them, and the rest in the city of Holon, just outside Tel Aviv.[16][17] There are also four Samaritan families residing in Binyamina-Giv'at Ada, Matan and Ashdod.

After the end of the British Mandate of Palestine and the subsequent establishment of the State of Israel, some of the Samaritans who were living in Jaffa emigrated to the West Bank and lived in Nablus. But by the late 1950s, around 100 Samaritans left the West Bank for Israel under an agreement with the Jordanian authorities in the West Bank.[64]

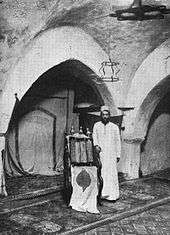

Until the 1980s, most of the Samaritans resided in the Samarian town of Nablus below Mount Gerizim. They relocated to the mountain itself near the Israeli settlement neighborhood of Har Brakha as a result of violence during the First Intifada (1987–1990). Consequently, all that is left of the Samaritan community in Nablus/Shechem itself is an abandoned synagogue. The Israeli army maintains a presence in the area.[17]

— John D. Whiting

The National Geographic Magazine, Jan 1920

As a small community physically divided between neighbors in a hostile region, Samaritans have been hesitant overtly to take sides in the Arab–Israeli conflict, fearing that doing so could lead to negative repercussions. While the Samaritan communities in both the West Bank's Nablus and Israeli Holon have assimilated to the surrounding culture, Hebrew has become the primary domestic language for Samaritans. Samaritans who are Israeli citizens are drafted into the military, along with the Jewish citizens of Israel.

_-_Samaritans_praying_during_Passover_holiday_ceremony_on_mount_Grizim.jpg)

Relations of Samaritans with Jewish Israelis and Muslim and Christian Palestinians in neighboring areas have been mixed. In 1954, Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi fostered a Samaritan enclave in Holon, Israel. Samaritans living in both Israel and in the West Bank enjoy Israeli citizenship. Samaritans in the Palestinian Authority-ruled territories are a minority in the midst of a Muslim majority. They had a reserved seat in the Palestinian Legislative Council in the election of 1996, but they no longer have one. Samaritans living in the West Bank have been granted passports by both Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

Survival

One of the biggest problems facing the community today is the issue of continuity. With such a small population, divided into only four families (Cohen, Tsedakah, Danfi and Marhib, a fifth family dying out in the twentieth century) and a general refusal to accept converts, there has been a history of genetic disorders within the group due to the small gene pool. To counter this, the Samaritan community has recently agreed that men from the community may marry non-Samaritan (primarily, Israeli Jewish) women, provided that the women agree to follow Samaritan religious practices. There is a six-month trial period prior to officially joining the Samaritan community to see whether this is a commitment that the woman would like to take. This often poses a problem for the women, who are typically less than eager to adopt the strict interpretation of biblical (Levitical) laws regarding menstruation, by which they must live in a separate dwelling during their periods and after childbirth. There have been a few instances of intermarriage. In addition, all marriages within the Samaritan community are first approved by a geneticist at Tel HaShomer Hospital, in order to prevent the spread of genetic disorders. In meetings arranged by "international marriage agencies",[71] a small number of Ukrainian women have recently been allowed to marry into the community in an effort to expand the gene pool.[72]

The Samaritan community in Israel also faces demographic challenges as young people leave the community and convert to Judaism. A notable example is Israeli television presenter Sofi Tsedaka, who has made a documentary about her leaving the community at age 18.

The head of the community is the Samaritan High Priest, who is selected by age from the priestly family, and resides on Mount Gerizim. The current high priest is Aabed-El ben Asher ben Matzliach who assumed the office in 2013.

Samaritanism

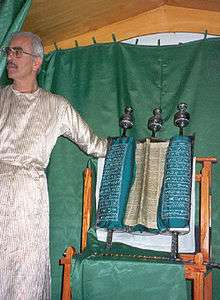

The Samaritan religion is based on some of the same books used as the basis of rabbinic Judaism, but differs from the latter. Samaritan scriptures include the Samaritan version of the Torah, the Memar Markah, the Samaritan liturgy, and Samaritan law codes and biblical commentaries. Samaritans appear to have texts of the Torah as old as the Masoretic Text; scholars have various theories concerning the actual relationships between these three texts.

Religious beliefs

- There is one God, YHWH, the same God recognized by the Hebrew prophets.

- The Torah was given by God to Moses.

- Mount Gerizim, not Jerusalem, is the one true sanctuary chosen by Israel's God.

- Many Samaritans believe that at the end of days, the dead will be resurrected by Taheb, a restorer (possibly a prophet, some say Moses).

- Paradise (heaven).

- The priests are the interpreters of the law and the keepers of tradition; scholars are secondary to the priesthood.

- The authority of post-Torah sections of the Tanakh, and classical Jewish rabbinical works (the Talmud, comprising the Mishnah and the Gemara) is rejected.

- They have a significantly different version of the Ten Commandments (for example, their 10th commandment is about the sanctity of Mount Gerizim).

The Samaritans retained the Ancient Hebrew script, the High Priesthood, animal sacrifices, the eating of lambs at Passover, and the celebration of Aviv in spring as the New Year. Yom Teruah (the biblical name for Rosh Hashanah), at the beginning of Tishrei, is not considered a New Year as it is in Judaism. The Samaritan Pentateuch differs from the Masoretic Text as well. Some differences are doctrinal: for example, the Samaritan Torah explicitly states that Mount Gerizim is "the place that God has chosen" for the Temple, as opposed to the Jewish Torah that refers to "the place that God will choose". Other differences are minor and seem more or less accidental.

Relationship to rabbinic Judaism

Samaritans refer to themselves as Bene Yisrael ("Children of Israel") which is a term used by all Jewish denominations as a name for the Jewish people as a whole. They however do not refer to themselves as Yehudim (Judeans), the standard Hebrew name for Jews.

The Talmudic attitude expressed in tractate Kutim is that they are to be treated as Jews in matters where their practice coincides with rabbinic Judaism but as non-Jews where their practice differs. Since the 19th century, rabbinic Judaism has regarded the Samaritans as a Jewish sect and the term "Samaritan Jews" has been used for them.[73]

Religious texts

Samaritan law is not the same as halakha (Rabbinical Jewish law). The Samaritans have several groups of religious texts, which correspond to Jewish halakhah. A few examples of such texts are:

- Torah

- Samaritan Pentateuch: There are some 6,000 differences between the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Masoretic Torah text, and, according to one estimate, 1,900 points of agreement between it and the Greek Septuagint version. Several passages in the New Testament would also appear to echo a Torah textual tradition not dissimilar to that conserved in the Samaritan text. There are several theories regarding the similarities. The variations, some corroborated by readings in the Old Latin, Syriac and Ethiopian translations, attest to the antiquity of the Samaritan text.[74][75][76]

- Historical writings

- Samaritan Chronicle, The Tolidah (Creation to the time of Abishah)

- Samaritan Chronicle, The Chronicle of Joshua (Israel during the time of divine favor) (4th century, in Arabic and Aramaic)

- Samaritan Chronicle, Adler (Israel from the time of divine disfavor until the exile)

- Hagiographical texts

- Samaritan Halakhic Text, The Hillukh (Code of halakhah, marriage, circumcision, etc.)

- Samaritan Halakhic Text, the Kitab at-Tabbah (Halacha and interpretation of some verses and chapters from the Torah, written by Abu Al Hassan 12th century CE)

- Samaritan Halakhic Text, the Kitab al-Kafi (Book of Halakhah, written by Yosef Al Ascar 14th century CE)

- Al-Asatir—legendary Aramaic texts from the 11th and 12th centuries, containing:

- Haggadic Midrash, Abu'l Hasan al-Suri

- Haggadic Midrash, Memar Markah—3rd or 4th century theological treatises attributed to Hakkam Markha

- Haggadic Midrash, Pinkhas on the Taheb

- Haggadic Midrash, Molad Maseh (On the birth of Moses)

- Defter, prayer book of psalms and hymns.[77]

Christian sources: New Testament

Samaria or Samaritans are mentioned in the New Testament books of Matthew, Luke, John and Acts. The Gospel of Mark contains no mention of Samaritans or Samaria. The best known reference to the Samaritans is the Parable of the Good Samaritan, found in the Gospel of Luke. The following references are found:

- When instructing his disciples as to how they should spread the word, Jesus tells them not to visit any Gentile or Samaritan city, but instead go to the "lost sheep of Israel". Matthew 10:5–6

- A Samaritan village rejected a request from messengers travelling ahead of Jesus for hospitality, because the villagers did not want to facilitate a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, a practice which they saw as a violation of the Law of Moses . Luke 9:51–53

- The Parable of the Good Samaritan. Luke 10:30–37.

- Jesus healed ten lepers, of whom only one returned to praise God, and he was a Samaritan. Luke 17:11–19, esp. 17:16

- Jesus asks a Samaritan woman of Sychar for water from Jacob's Well. Thereafter many of the Samaritans from her town become followers of Jesus. This woman considered herself and her people to be Israelites, descendants of Jacob. John 4:4-42

- Jesus is accused of being a Samaritan and being demon-possessed. He denies having a demon, but makes no comment on the Samaritan accusation. John 8:48

- Christ tells them that they would receive power when the Holy Spirit comes upon them, and that they would be his witnesses in "Jerusalem, and in all Judaea, and in Samaria, and unto the uttermost part of the earth." Acts 1:8

- The Apostles are being persecuted. Philip preaches the Gospel to a city in Samaria; and the Apostles in Jerusalem hear about it. So they send the Apostles Peter and John to pray for and lay hands on the baptized believers, who then receive the Holy Spirit (vs. 17). They then return to Jerusalem, preaching the Gospel "in many villages of the Samaritans". Acts 8:1–25

- Acts 9:31 says that at that time the churches had "rest throughout all Judaea and Galilee and Samaria".

- Acts 15:2–3 says that Paul and Barnabas were "being brought on their way by the church" and that they passed through "Phenice and Samaria, declaring the conversion of the Gentiles". (Phoenicia in several other English versions).

The rest of the New Testament makes no specific mention of Samaria or Samaritans.

Media

The Samaritan News, a monthly magazine started in 1969, is written in Samaritan Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic, and English and deals with current and historical issues with which the Samaritan community is concerned. The Samaritan Update is a bi-monthly e-newsletter for Samaritan Studies.[78]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 The Samaritan Update Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ Barbati, Gabrielle (January 21, 2013). "Israeli Election Preview: The Samaritans, Caught Between Two Votes". International Business Times. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Joshua, The Samaritan Book Of:". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ↑ Schreiber, Monika (2014). The Comfort of Kin: Samaritan Community, Kinship, and Marriage. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-27425-9.

- 1 2 Fried, Lisbeth S. (2014). Ezra and the Law in History and Tradition. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-61117-410-6.

- ↑ Burgess, Henry (2003). Journal of Sacred Literature and Biblical Record, April 1855 to July 1855. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-5612-8.

- ↑ Lipschitz, Oded; Knoppers, Gary N.; Albertz, Rainer (2007). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. pp. 157, 177 n. 13. ISBN 978-1-57506-130-6.

- ↑ (2 Kings, 17:30). "According to the rabbis, his emblem was a cock".

- ↑ Clarke's Commentary on the Bible - 2 Kings 17:30

- 1 2 3 "Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation" (PDF). (855 KB), Hum Mutat 24:248–260, 2004.

- 1 2 Genetics and the Jewish identity By DIANA MUIR APPELBAUM, PAUL S. APPELBAUM, MD \ 02/11/2008, Jerusalem Post

- ↑ Tsedaka, Benyamim (2013-04-26). The Israelite Samaritan Version of the Torah. ISBN 9780802865199. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- 1 2 M. Levy-Rubin, "New evidence relating to the process of Islamization in Palestine in the Early Muslim Period - The Case of Samaria", in: Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 43 (3), p. 257–276, 2000, Springer

- 1 2 Fattal, A.(1958) Le statut légal des non-Musulman en pays d'Islam, Beyrouth: Imprimerie Catholique, p. 72–73.

- ↑ Alan David Crown, Reinhard Pummer, Abraham Tal (eds.), A Companion to Samaritan Studies, Mohr Siebeck, 1993 pp.70-71.

- 1 2 Friedman, Matti (2007-03-18). "Israeli sings for her estranged people". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. pp. (Sun March 18, 2007, 2:45 PM ET). Archived from the original on 2007-03-26.

Today there are precisely 705 Samaritans, according to the sect's own tally. Half live near the West Bank city of Nablus on Mt. Gerizim [...]. The other half live in a compound in the Israeli city of Holon, near Tel Aviv.

- 1 2 3 Dana Rosenblatt (October 14, 2002). "Amid conflict, Samaritans keep unique identity". CNN.com.

- ↑ Angel Sáenz-Badillos; translated by John Elwolde. (1993). A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- ↑ K'fir, Amnon (May 2, 2007). "The Samaritans' Passover sacrifice". YNET News.

- ↑ Shulamit Sela, The Head of the Rabbanite, Karaite and Samaritan Jews: On the History of a Title, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 57, No. 2 (1994), pp. 255–267

- ↑ "- - nrg - ... :". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ynet סופי צדקה עושה שבת (וחג) - יהדות". ynet. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Bible Dictionary, 5:941 (New York: Doubleday, 1996, c1992).

- ↑ Gesenius Biblical Hebrew Dictionary. "Biblical Hebrew Lexicon entry#SMRI". Blue Letter Bible. King James Version.

- ↑ Ibn Manzur (19??). "entry SMR". Lisan al Arab. 21. Al-dar al-Misriya li-l-talif wa-l-taryamar. ISBN 978-0-86685-541-9. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Gessinius Lexicon Hebrew entry#H8104". Hebrew. Blue Letter Bible.

- ↑ Reinhard Pummer (2002). Early Christian Authors on Samaritans and Samaritanism: Texts, Translations and Commentary. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 123, 42, 156. ISBN 978-3-16-147831-4.

- ↑ R. J. Coggins (1975). Samaritans and Jews: the origins of Samaritanism reconsidered. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-8042-0109-4.

- ↑ Saint Epiphanius (Bishop of Constantia in Cyprus) (1 January 1987). The Panarion of Ephiphanius of Salamis: Book I (sects 1–46). BRILL. p. 30. ISBN 978-90-04-07926-7.

- ↑ Paul Keseling (1921). Die chronik des Eusebius in der syrischen ueberlieferung (auszug). Druck von A. Mecke. p. 184.

- ↑ Origen (1896). The Commentary of Origen on S. John's Gospel: The Text Rev. with a Critical Introd. & Indices. The University Press.

- ↑ Grunbaum, M.; Geiger, Rapoport (1862). "mitgetheilten ausfsatze uber die samaritaner". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft: ZDMG. 16. Harrassowitz. pp. 389–416.

- ↑ The Keepers, An Introduction to the History and Culture of the Samaritans, by Robert T. Anderson and Terry Giles, Hendrickson Publishing, 2002, pages 11–12

- ↑ 2 Kings 17.

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities 9.277–91).

- ↑ See the wording of 2 Kings 17 which mentions Shalmaneser in verse 3 but the "king of the Assyrians" from verse 4 onward.

- ↑ Yitzakh Magen, 'The Dating of the First Phase of the Samaritan Temple on Mt Gerizim in Light of Archaeological Evidence,' in Oded Lipschitz, Gary N. Knoppers, Rainer Albertz (eds.) Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E., Eisenbrauns, 2007 pp.157–212 .p.187 'The author of Chronicles conceals the information that is given prominence in Kings, and vice versa.' 'The books of Ezra and Nehemiah adopt a narrow sectarian approach that seeks to maintain the uniqueness and racial purity of the exiles in Babylonia, while Chronicles is more broad-minded and views the Israelite nation as a great people that includes all the tribes, both Judah and Israel.'

- ↑ 2Chronicles 34:9

- ↑ Jeremiah 41:5

- ↑ Yitzakh Magen, 'The Dating of the First Phase of the Samaritan Temple on Mt Gerizim in Light of Archaeological Evidence,' in Oded Lipschitz, Gary N. Knoppers, Rainer Albertz (eds.) Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E., Eisenbrauns, 2007 pp.157–212. p.186

- ↑ Yitzakh Magen, 'The Dating of the First Phase of the Samaritan Temple on Mt Gerizim in Light of Archaeological Evidence,' in Oded Lipschitz, Gary N. Knoppers, Rainer Albertz (eds.) Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E., Eisenbrauns, 2007 pp.157–212. p.187.

- ↑ Magnar Kartveit (2009). The Origin of the Samaritans. BRILL. pp. 168–171. ISBN 9004178198. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ Michael D. Coogan, "A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament" page 363, 2009.

- ↑ Mark A. Powell, "Introducing the New Testament: A Historical, Literary, and Theological Survey" 'Ch.01 The People of Palestine at the Time of Jesus', Baker Academic, 2009.

- ↑ (Nimrud Prisms, COS 2.118D, pp. 295-296)

- ↑ Yitzhak Magen, The Dating of the First Phase of the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim in the Light of the Archaeological Evidence (in Oded Lipschitz, Gary N. Knoppers, Rainer Albertz, eds, "Judah and Judeans in the Fourth Century BC", Eisenbrauns, 2007). Books.google.com.au. 2007. ISBN 9781575061306. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ http://www.grizimtour.com/Tourism.htm Archived June 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ John 4:9;27

- ↑ "Jesus and the Samaritan Woman / A Samaritan Woman Approaches:1". Christiancourier.com. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ↑ See: Jonathan Bourgel, "The Destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus: A Reconsideration", JBL 135/3 (2016), pp. 505-523

- ↑ Greg Johnston. "Israel & the Palestinian Territories Travel Information and Travel Guide". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ See: Jonathan Bourgel, "The Samaritans in the Eyes of the Romans: The Discovery of an Identity," Cathedra 144 (2012), 7-20 (in Hebrew).

- ↑ L. Michael White (1987). "The Delos Synagogue Revisited Recent Fieldwork in the Graeco-Roman Diaspora". Harvard Theological Review. 80 (2): 133–160. doi:10.1017/s0017816000023579.

- ↑ Lidia Matassa (2007). "Unravelling the Myth of the Synagogue on Delos". Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. 25: 81–115.

- ↑ Malalas, 15.

- ↑ Procopius, Buildings, 5.7.

- ↑ Alan David Crown, The Samaritans, Mohr Siebeck, 1989, ISBN 3-16-145237-2, pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Pummer 1987 p.4.

- ↑ Reinhard Pummer, The Samaritans, BRILL, 1987 p.17.

- ↑ Benjamin Z. Kedar, "The Frankish period", in The Samaritans, ed. Alan D. Cross (Tübingen, 1989), pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Monika Schreiber, https://books.google.com/books?id=4We7AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA46 The Comfort of Kin: Samaritan Community, Kinship, and Marriage, BRILL, 2014 p.46.

- 1 2 3 4 Sean Ireton (2003). "The Samaritans - The Samaritans: Strategies for Survival of an Ethno-religious Minority in the Twenty First Century". Anthrobase. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- 1 2 E. Mills (1933). Census of Palestine 1931. Volume I. Alexandria: Government of Palestine. p. 87.

- 1 2 The Political History of the Samaritans - zajel / An-Najah National University, January 24, 2005

- 1 2 3 Ben Zvi, Yitzhak (October 8, 1985). Oral telling of Samaritan traditions: Volume 780-785. A.B. Samaritan News. p. 8.

- ↑ http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2016/10/economist-explains-14

- ↑ Shen, P; Lavi T; Kivisild T; Chou V; Sengun D; Gefel D; Shpirer I; Woolf E, Hillel J, Feldman MW, Oefner PJ (2004). "Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation" (PDF). Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248–260. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. PMID 15300852.

- ↑ Cruciani, F.; La Fratta, R.; Torroni, A.; Underhill, P. A.; Scozzari, R. (April 2006). "Molecular Dissection of the Y Chromosome Haplogroup E-M78 (E3b1a): A Posteriori Evaluation of a Microsatellite-Network-Based Approach Through Six New Biallelic Markers". Human Mutation. 27 (8): 831–2. doi:10.1002/humu.9445. PMID 16835895.

- ↑ Yohanan Aharoni, Michael Avi-Yonah, Anson F. Rainey, Ze'ev Safrai, The Macmillan Bible Atlas, 3rd Edition, Macmillan Publishing: New York, 1993, p. 115. A posthumous publication of the work of Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni and Michael Avi-Yonah, in collaboration with Anson F. Rainey and Ze'ev Safrai.

- ↑ "The Samaritan Update". Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Patience, Martin (6 February 2007). "Ancient community seeks brides abroad". BBC News. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ↑ Ferguson, Jane (8 January 2013). "West Bank Samaritans fight extinction". Mount Gerizin: Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ Shulamit Sela, The Head of the Rabbanite, Karaite and Samaritan Jews: On the History of a Title, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 57, No. 2 (1994), pp. 255-267

- ↑ James VanderKam, Peter Flint, The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance For Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity, A&C Black, 2nd ed. 2005 p.95.

- ↑ Timothy Michael Law, When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible, Oxford University Press, USA, 2013 p.24.

- ↑ Isac Leo Seeligmann, The Septuagint Version of Isaiah and Cognate Studies, Mohr Siebeck 2004 pp.64ff.

- ↑ Samaritan Documents, Relating To Their History, Religion and Life, translated and edited by John Bowman, Pittsburgh Original Texts & Translations Series Number 2, 1977.

- ↑ The Samaritan News

Further reading

- Montgomery, James Alan (2006) [1907]. The Samaritans, the Earliest Jewish Sect. The Bohlen Lectures for 1906. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock. ISBN 1-59752-965-6.

- Thomson, J. E. H. (1919). Tha Samaritans: Their Testimony to the Religion of Israel. Edinburgh & London: Oliver and Boyd.

- Gaster, Moses (1925). The Samaritans: Their History, Doctrines and Literature. The Schweich Lectures for 1923. Oxford University Press.

- Macdonald, John (1964). The Theology of the Samaritans. New Testament Library. London: SCM Press.

- Purvis, James D. (1968). The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Origin of the Samaritan Sect. Harvard Semitic Monographs. 2. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Bowman, John (1975). The Samaritan Problem. Pickwick Press.

- Coggins, R. J. (1975). Samaritans and Jews: The Origins of Samaritanism Reconsidered. Growing Points in Theology. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Pummer, Reinhard (1987). The Samaritans. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-07891-6.

- Hjelm, Ingrid (2000). Samaritans and Early Judaism: A Literary Analysis. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. Supplement Series, 303. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 1-84127-072-5.

- Hjelm, Ingrid, "Mt Gerezim and Samaritans in Recent Research", in Samaritans: Past and Present: Current Studies, Edited by Mor, Menachem; Reiterer, Friedrich V.; Winkler, Waltraud (Berlin, New York) (DE GRUYTER) 2010, Pages 25–44, eBook ISBN 978-3-11-021283-9, Print ISBN 978-3-11-019497-5

- Anderson, Robert T.; Giles, Terry (2002) [2002]. The Keepers: An Introduction to the History and Culture of the Samaritans. Hendrickson Publishing. ISBN 1-56563-519-1.

- Anderson, Robert T., Giles, Terry, "Tradition kept: the literature of the Samaritans"(Hendrickson Publishers, 2005)

- Crown, Alan David (2005) [1984]. A Bibliography of the Samaritans: Revised Expanded and Annotated (3rd ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-5659-X.

- Heinsdorff, Cornel (2003). Christus, Nikodemus und die Samaritanerin bei Juvencus. Mit einem Anhang zur lateinischen Evangelienvorlage (= Untersuchungen zur antiken Literatur und Geschichte, Bd. 67), Berlin/New York. ISBN 3-11-017851-6

- Zertal, Adam (1989). "The Wedge-Shaped Decorated Bowl and the Origin of the Samaritans". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 276. (November 1989), pp. 77–84.