Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat

| Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat | |

|---|---|

|

الجماعة السلفية للدعوة والقتال Participant in the Algerian Civil War and the Insurgency in the Maghreb | |

| Active | 1998–2007 |

| Ideology | |

| Leaders |

Hassan Hattab (1998–2003) Nabil Sahraoui (2003–2004) Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud (2004–2007) |

| Strength | hundreds–4,000[1] |

| Originated as | Armed Islamic Group (until 2004) |

| Became |

|

| Allies |

|

| Opponents | |

The Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (Arabic: الجماعة السلفية للدعوة والقتال al-Jamā‘ah as-Salafiyyah lid-Da‘wah wal-Qiṭāl), known by the French acronym GSPC (Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat),[2] was an Algerian terrorist faction in the Algerian Civil War founded in 1998 by Hassan Hattab, a former regional commander of the Armed Islamic Group (GIA). After Hattab was ousted from the organization in 2003, the group officially pledged support for al-Qaeda, and in 2007 formed the basis for al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

History

The Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) was founded by Hassan Hattab, a former Armed Islamic Group (GIA) regional commander who broke with the GIA in 1998 in protest over the GIA's slaughter of civilians. After an amnesty in 1999, many former GIA fighters laid down their arms, but a few remained active, including members of the GSPC.[3]

Estimates of the number of GSPC members vary widely, from a few hundred to as many as 4,000.[1] In September 2003, it was reported that Hattab had been deposed as national emir of the GSPC and replaced by Nabil Sahraoui (Sheikh Abou Ibrahim Mustapha), a 39-year-old former GIA commander who was subsequently reported to have pledged GSPC's allegiance to al-Qaeda,[4] a step which Hattab had opposed.[3][5] Following the death of Sahraoui in June 2004, Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud became the leader of the GSPC.[6] Abdelmadjid Dichou is also reported to have headed the group.[7]

A splinter or separate branch of Hattab's group, the Free Salafist Group (GSL), headed by El Para, was linked to the kidnapping of 32 European tourists in Algeria in early 2003.[3] Other sources illustrate the involvement of the Algerian intelligence services in exaggerating the claims about terrorist threats in the Sahara, and the supposed alliance between this group and Al-Qaeda. Some of the reputation of El Para is also attributed to the Algerian government, as a possible employer, and it has been alleged that certain key events, such as kidnappings, were staged, and that there was a campaign of deception and disinformation originated by the Algerian government and perpetuated by the media.[8][9]

By March 2005, it was reported that the GSPC "may be prepared to give up the armed struggle in Algeria and accept the government's reconciliation initiative."[10] in March 2005, the group's former leader, Hassan Hattab, called on its members to accept a government amnesty under which they were offered immunity from prosecution in return for laying down their arms.[11] However, in September 2006, the top Al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahri announced a "blessed union" between the groups in declaring France an enemy. They said they would work together against French and American interests.[12]

International links

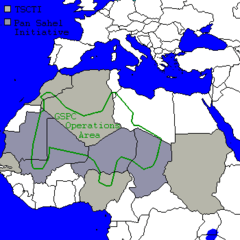

Algerian officials and authorities from neighbouring countries have speculated that the GSPC may have been active outside Algeria. These activities may relate to the GSPC's alleged long-standing involvement with smuggling, protection rackets, and money laundering across the borders of Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Libya and Chad, possibly to underpin the group's finances.[3] However, recent developments seem to indicate that a splinter group may have sought refuge in the Tuareg regions of northern Mali and Niger following crackdowns by Algerian government forces in the north and south of the country since 2003. French secret services report that the group has received funding from the country of Qatar.[13]

Some observers, including Jeremy Keenan, have voiced doubts regarding the GSPC's capacity to carry out large-scale attacks, such as the one attributed to it in northeastern Mauritania during the "Flintlock 2005" military exercise.[14] They suspect the involvement of Algeria's Department of Intelligence and Security is an effort to improve Algeria's international standing as a credible partner in the War on Terrorism, and to lure the United States into the region.[8]

Allegations of GSPC links to al-Qaeda predate the September 11 attacks. As followers of a Qutbist strand of Salafist jihadism, the members of the GSPC are thought to share al-Qaeda's general ideological outlook. After the deposition of Hassan Hattab, various leaders of the group pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda. Some observers have argued that the GSPC's connection to al-Qaeda was merely opportunistic, not operational. Claims of GSPC activities in Italy[15] were disputed by other sources, who said that there is no evidence of any engagement in terrorist activities against US, European or Israeli targets: "While the GSPC ... established support networks in Europe and elsewhere, these have been limited to ancillary functions (logistics, fund-raising, propaganda), not acts of terrorism or other violence outside Algeria."[3] Investigations in France and Britain have concluded that young Algerian immigrants sympathetic to the GSPC or al-Qaeda have taken up the name without any real connection to either group.[1]

Similar claims of links between the GSPC and Abu Musab Al Zarqawi in Iraq[16] were based on purported letters to Zarqawi by GSPC leader Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud.[17] In a September 2005 interview, Wadoud hailed Zarqawi's actions in Iraq.[6] Like the GSPC's earlier public claims of allegiance to al-Qaeda, they are thought to be opportunistic legitimisation efforts of the GSPC's leaders due to the lack of representation in Algeria's political sphere.[3]

In 2005, after years of absence, the United States showed renewed military interest in the region[18][19] through involvement in the "Flintlock 2005" exercise, which involved US Special Forces training soldiers from Algeria, Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, and Chad. The United States alleged that the Sahel region had become a training ground for Islamist recruits.[20] However, the two most important pieces of evidence of 'terrorist activity' – the tourist kidnapping of 2003 and the attack on the Mauritanian army base just as "Flintlock" got underway – have subsequently been called into question.[14][21]

Observers said that the region's governments have much to gain from associating[22] local armed movements and long-established smuggling operations with al-Qaeda and the global "War on Terrorism".[14] In June 2005, while the "Flintlock" exercise was still underway, Mauritania asked "Western countries interested in combating the terrorist surge in the African Sahel to supply it with advanced military equipment."[23]

Timeline of attacks

- 23 November 2002: A group of Algerian soldiers are ambushed. Nine died and twelve were wounded.

- February 2003: 32 European tourists are kidnapped. One died of heat stroke, seventeen hostages were rescued by Algerian troops on 13 May 2003, and the remainder were released in August 2003.[24]

- 12 February 2004: Near Tighremt, Islamic extremists ambush a police patrol, killing seven police officers and wounding three others. The assailants also seized firearms and three vehicles.[25]

- 7 April 2005: In Tablat, Blida Province, armed assailants fire on five vehicles at a fake road block, killing 13 civilians, wounding one other and burning five vehicles.[26]

- 15 October 2006: In Sidi Medjahed, Ain Defla, assailants attack and kill eight private security guards by unknown means.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 BBC Documentary about increased US military focus on the Sahara region. August 2005.

- ↑ Steinberg, Guido; Isabelle Werenfels (November 2007). "Between the 'Near' and the 'Far' Enemy: Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb". Mediterranean Politics. 12 (3): 407–13. doi:10.1080/13629390701622473.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Islamism, Violence and Reform in Algeria: Turning the Page (Islamism in North Africa III)]". International Crisis Group Report,. 30 July 2004. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ↑ Algerian group backs al-Qaeda, BBC News, 23 October 2003

- ↑ Interview with the Former Leader of the Salafist Group for Call and Combat, Ash-Sharq al-Awsat, 17 October 2005

- 1 2 Interview with Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud, commander of the GSPC, 26 September 2005 (globalterroralert.com website) (pdf) Archived 21 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC)", Terrorist Organizations, World Statesman. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- 1 2 El Para, the Maghreb’s Bin Laden – who staged the tourist kidnappings? by Salima Mellah and Jean-Baptiste Rivoire, Le Monde Diplomatique, February 2005

- ↑ Keenan, Jeremy (26 September 2006). "The Collapse of the Second Front". Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Georges Rassi, "End of Insurgency", al-Mustaqbal, as reported in MidEast Mirror, 24 March 2005. Quoted in Islamist Terrorism in the Sahel: Fact or Fiction?

- ↑ Top Algerian Islamist slams Qaeda group, urges peace, Reuters, 30 March 2006 Archived 17 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Al-Qaida joins Algerians against France", AP, 14 September 2006

- ↑ Deep Read: Malian tinderbox – A dangerous puzzle. 9 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 US targets Sahara 'terrorist haven', BBC News, 8 August 2005

- ↑ GSPC in Italy: The Forward Base of Jihad in Europe by Kathryn Haar, Jamestown Foundation, 9 February 2006) Archived 8 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "'The Al-Qaeda Organization in the Islamic Maghreb': The Evolving Terrorist Presence in North Africa", Inquiry and Analysis, Middle East Media Research Institute, 7 March 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ↑ Algerian terror group seeks Zarqawi's help, UPI 2 May 2006

- ↑ General Sees Expanding Strategic Role for U.S. European Command In Africa by Charles Cobb Jr., American Enterprise Institute, 16 April 2004 Archived June 28, 2007, at WebCite

- ↑ Africa Command Not European Command, Says Official by Charles Cobb Jr., American Enterprise Institute, 4 May 2004 Archived June 28, 2007, at WebCite

- ↑ DoD Press Release about the "Flintlock 2005" military exercise, 17 June 2005 Archived 14 July 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ L'attaque contre la garnison de Lemgheity toujours à la une, Panapress, Jeune Afrique, 16 June 2005

- ↑ Un Marocain arrêté en Mauritanie pour terrorisme, La Libération (Casablanca), 8 June 2006

- ↑ Mauritanian authorities transform Lemgheity post into military base, Al-Akhbar website in Arabic 1410 gmt 22 Jun 5, BBC Monitoring Service.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS – Africa – Sahara hostages freed". Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ View Incident

- ↑ View Incident

- ↑ View Incident