SS Arandora Star

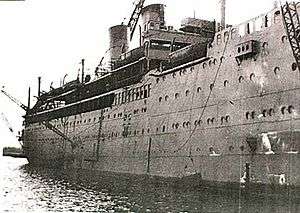

Arandora Star as a transport in 1940 (Royal Navy photograph) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

Arandora (1927–29) Arandora Star (1929–40) |

| Owner: | Blue Star Line |

| Port of registry: | London |

| Route: |

|

| Ordered: | 1925 |

| Builder: | Cammell Laird & Co, Birkenhead |

| Yard number: | 921 |

| Launched: | 4 January 1927 |

| Completed: | May 1927 |

| In service: | 1927 |

| Out of service: | 1940 |

| Refit: |

|

| Nickname(s): | "The Wedding Cake" or the "Chocolate Box" due to her paint scheme. |

| Fate: | Torpedoed and sunk 2 July 1940 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | ocean liner and refrigerated cargo ship (1927–29); cruise liner (1929–39); troop ship (1940) |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: | 512.2 feet (156.1 m) |

| Beam: | 68.3 feet (20.8 m) |

| Height: |

|

| Decks: | 7 decks |

| Installed power: | 2,078 NHP |

| Propulsion: | four steam turbines, single reduction geared onto two propeller shafts |

| Speed: | 16 knots (30 km/h) |

| Capacity: |

|

| Notes: |

|

SS Arandora Star was a British passenger ship of the Blue Star Line. She was built in 1927 as an ocean liner and refrigerated cargo ship, converted in 1929 into a cruise ship and requisitioned as a troop ship in World War II. At the end of June 1940 she was assigned the task of transporting German and Italian internees and prisoners of war to Canada. On 2 July 1940 she was sunk in controversial circumstances by a German U-boat with a large loss of life, 865.

Construction

In 1925 Blue Star ordered a set of new liners for its new London – Rio de Janeiro – Buenos Aires route. Cammell Laird of Birkenhead built three sister ships: Almeda, Andalucia and Arandora. John Brown & Company of Clydebank built two: Avelona and Avila. Together the quintet came to be called the "luxury five".[1]

Cammell Laird launched Arandora on 4 January 1927 and completed her in May.[2] As originally built she measured 12,847 gross register tons (GRT), was 512.2 feet (156.1 m) long, had a beam of 68.3 feet (20.8 m) and accommodated 164 first class passengers. She had a service speed of 16 knots (30 km/h). A major refit in 1929 reduced her cargo space and increased her passenger accommodation to turn her into a cruise ship.

Peacetime service

As Arandora she sailed from London to the east coast of South America from 1927 to 1928. In 1929 she was sent to Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company Limited of Glasgow for refitting. In the refit, her gross tonnage was increased to 14,694 and first class accommodation was increased to 354 passengers. A tennis court was also placed abaft the funnels on the boat deck and a swimming pool was installed in the after well deck. Upon completion, she returned to service as a full-time luxury cruise ship. At the time of this refit, she was also renamed Arandora Star. The renaming was done to avoid confusion with Royal Mail Ships which typically bore names beginning and ending in 'A'.

As a cruise ship Arandora Star was based mainly in Southampton, and voyaged to many different destinations, calling in some instances at home ports such as Immingham.[3] Cruises included Norway, the Northern capitals, the Mediterranean, the West Indies, Panama, Cuba, and Florida. Arandora Star also had two unique nicknames because of her colour scheme of a white hull with scarlet ribbon. The nicknames most frequently used were "The Wedding Cake" or the "Chocolate Box".[4]

World War II service

When the UK entered World War II on September 1939 Arandora Star was en route from Cherbourg to New York. She returned to Britain via Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she joined the very first HX-series convoy, Convoy HX 1.[5]

At the end of September the Admiralty assessed the ship at Dartmouth, Devon and decided she was unsuitable for conversion to an armed merchant cruiser.[4] In December she was ordered to Avonmouth where she was fitted with the Admiralty Net Defence anti-torpedo system, consisting of underwater wire mesh suspended from booms either side of the ship.[6] She was fitted out at Avonmouth and then spent three months based at Portsmouth testing nets of various gauges in the English Channel. On tests the system was successful at catching torpedoes and reduced Arandora Star's speed by only 1 knot (1.85 km/h). In March 1940 the ship was sent to Devonport where the equipment was removed. She was then sent to Liverpool for orders.[7]

On 30 May the ship left Liverpool for Norway to help evacuate Allied troops. She sailed unescorted via the Firth of Clyde to Harstad, where she embarked 1,600 personnel, most of them RAF plus some French and Polish troops.[8] She left Harstad on 7 June[5] and took her evacuees to Glasgow.

On 14 June the ship left Glasgow, going via Swansea to rescue troops or refugees from Brest in Brittany. Continuous Luftwaffe attacks on the port and town prevented her from entering, and only half a dozen refugees managed to get out by boat and join the ship. Arandora Star escaped with the aid of a destroyer, which gave anti-aircraft cover and came under heavy air attack. The liner took her handful of evacuees to Falmouth, where she bunkered. She then went to Quiberon Bay on the Bay of Biscay, where she evacuated about 300 people from Saint-Nazaire on 17 June. Sources disagree whether she took these to Falmouth[8] or Plymouth.[5] Arandora Star was lucky that Saint-Nazaire was fairly quiet when she visited. On the same day Luftwaffe aircraft sank RMS Lancastria there, killing several thousand people.

Arandora Star's next trip to France was to the southwest near the border with Spain. There she found Bayonne under Luftwaffe attack but assisted by a destroyer she picked up about 500 people who were in overloaded small craft adrift off the beach. These she took to Falmouth before returning to the same part of France. She entered Saint-Jean-de-Luz where some Polish Army troops were trapped. She embarked about 1,700 troops and refugees including the Polish staff, and left just in time as Luftwaffe aircraft approached to bomb the town. She took her evacuees to Liverpool.[9]

Sinking

What became Arandora Star's final voyage was to take Italian and German internees and German prisoners of war to Canada.[2] In Liverpool on 27–30 June she embarked 734 interned Italian men, 479 interned German men, 86 German prisoners of war and 200 military guards. Her crew numbered 174 officers and men.[10] Her Master was Captain Edgar Wallace Moulton. The ship was bound for St John's, Newfoundland, and her internees for Canadian internment camps.

Sources disagree as to whether the ship left Liverpool on 30 June or at 0400 hrs on 2 July 1940. She sailed unescorted, and early on the morning of 2 July she was about 75 miles west of Bloody Foreland when U-47, commanded by U-Boat ace Günther Prien, struck her with a single torpedo. Prien believed the torpedo to be faulty,[11] but it detonated against Arandora Star's starboard side, flooding her after engine room. All engine room personnel, including two engineer officers, were killed. Her turbines, main generators and emergency generators were all immediately out of action, and therefore all lights and communications aboard.[10]

Chief officer Frederick Brown gave the ship's position to the radio officer, who transmitted a distress signal.[12] At 0705 hours Malin Head radio acknowledged the message and retransmitted to Land's End and to Portpatrick.

Lifeboats

The cruise ship carried 14 lifeboats and 90 liferafts. The torpedo destroyed one starboard and disabled the davits and falls of another.[10] Two boats were damaged during their launch and thus useless. The crew successfully launched the remaining 10 boats and more than half the liferafts. Some boats were overloaded by prisoners descending the falls and side ladders, but many of the Italians were too afraid to leave the ship.[12] At least four of the remaining lifeboats were launched with a very small number of survivors. One other lifeboat was swamped and sank shortly after being launched.

One of the internees on Arandora Star was Captain Otto Burfeind, who had been interned after scuttling his ship, the Adolph Woermann. Burfeind stayed aboard Arandora Star organizing her evacuation until she sank and he was lost.

The ship listed further to starboard, and at 0715 hrs Captain Moulton and his senior officers walked over the side into the rising water, leaving behind many Italians who were still too afraid to leave the ship. At 0720 hrs the ship rolled over, raised her bow in the air and sank.[12] 805 people were killed, including Captain Moulton, 12 of his officers, 42 of his crew and 37 of the military guards.[13]

"I could see hundreds of men clinging to the ship. They were like ants and then the ship went up at one end and slid rapidly down, taking the men with her... Many men had broken their necks jumping or diving into the water. Others injured themselves by landing on drifting wreckage and floating debris near the sinking ship"— Sergeant Norman Price[14]

Rescue

At 0930 hrs an RAF Coastal Command Short Sunderland flying boat flew over and dropped watertight bags containing first aid kits, food, cigarettes and a message that help was coming. The aircraft circled until 1300 hrs,[12] when the Canadian C-class destroyer HMCS St. Laurent arrived and rescued 868 survivors,[13] of whom 586 were detainees. The injured were taken to Mearnskirk Hospital in Newton Mearns, Glasgow. One of the survivors was the athletics coach Franz Stampfl.

The UK War Cabinet received a report on the disaster on 3 July 1940.[15] Its impact was overshadowed to an extent by the Royal Navy attack on Mers-el-Kébir, French Algeria that sank the French fleet.Throughout August bodies were washed up on the Irish shore. The first was 71-year-old Ernesto Moruzzi, who was found at Cloughglass, Burtonport. Four others were found on the same day, 30 July. During August 1940, 213 bodies were washed up on the Irish coast, of which 35 were from Arandora Star and a further 92 unidentified, most probably from the Arandora Star.[16]

Although many were rescued it's worth noting that both the Italian and German survivors were taken back to Scotland as part of the rescue mission, but were not released on their return despite many being traders and nationalized Scottish citizens

Citations

Captain Moulton was posthumously awarded Lloyd's War Medal for Bravery at Sea. Captain Burfeind was posthumously cited for his heroism in the evacuation, and the Canadian commander Harry DeWolf was cited for his heroism in the rescue.

Wreck and memorials

The wreck's position is 56°30′N 10°38′W / 56.500°N 10.633°W.

In the weeks following the Arandora Star's sinking many bodies of those who perished were carried by the sea to various points in Ireland and the Hebrides. In the small graveyard of Termoncarragh, Belmullet, County Mayo, Luigi Tapparo, an internee, from Edinburgh, and John Connelly, a Lovat Scout, lie buried side by side. Belmullet gardaí received a call from Annagh Head that another body had been found. From a service book on the body, Garda Sergeant Burns identified 27-year-old Trooper Frank Carter of the Royal Dragoons, a career soldier and a married man, from Kilburn, London. Ceazar Camozzi (1891–1940) from Iseo, Italy was washed ashore on the Inishowen peninsula, County Donegal and is buried at Sacred Heart graveyard, Carndonagh. 46 German civilian detainees, who were being shipped from England to Canada for internment when the ship sank, were buried in the German war cemetery in Glencree, County Wicklow.

An unidentified sailor, unrecognisable other than for a tattoo bearing the name "Chrissie", was washed ashore near Newhouse, on the Atlantic coast of Kintyre, Argyll and, after official investigation, buried at the local churchyard of Killean, Kintyre, Argyll.

A memorial chapel was built in a cemetery in Bardi, home town of 48 of the dead. A street in Bardi was renamed Via Arandora Star.

St Peter's Italian Church in Clerkenwell, London, unveiled a memorial plaque in 1960. Each year a mass is held on the first Sunday in November, close to the anniversary of the unveiling of the plaque.

In 2004 the Italian town of Lucca unveiled a monument to 31 local men lost in the sinking, located in the courtyard of the museum of the Paolo Cresci Foundation for the History of Italian Emigration.

Numerous bodies were found on the Scottish island of Colonsay. A memorial was unveiled on Colonsay on 2 July 2005, the 65th anniversary of the tragedy, at the cliff where the body of Giuseppe Delgrosso was found.[17]

A bronze memorial plaque was unveiled on 2 July 2008 at the Church of Our Lady and St Nicholas, Liverpool. It was relocated to the Pier Head in front of the old Mersey Docks and Harbour Board building after building work was finished.

In 2009, the 69th anniversary of the sinking, the Mayor of Middlesbrough unveiled a memorial in the town hall commemorating the town's 13 interned Italians held in cells there prior to deportation and death on the Arandora Star's final voyage.[18]

On 2 July 2010, the 70th anniversary of the sinking, a new memorial was unveiled in St David's Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral, Cardiff by the Arandora Star Memorial Fund in Wales.[19]

On the same day, 2 July 2010, a memorial cloister garden was opened next to St Andrew's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Glasgow. Archbishop Mario Conti said at the time he hoped the monument would be a "fitting symbol" of the friendship between Scotland and Italy.[20]

The wreckage of one of the lifeboats remains visible at Knockvologan beach on the Ross of Mull, largely buried but with its iron suspension hooks still above the sand.

See also

- List by death toll of ships sunk by submarines

- Almeda Star — one of Arandora Star's sister ships, torpedoed and sunk with all 360 onboard lost in January 1941

- Avila Star — another of Arandora Star's sister ships, torpedoed and sunk in July 1942 with the loss of 84 lives

- RMS Nova Scotia — a UK liner sunk in November 1942 while carrying interned Italian civilians and prisoners of war with the loss of 858 of the 1,052 people aboard

- enemy aliens

References

- ↑ "Blue Star's S.S. "Almeda Star" 1". One of The Luxury Five. Blue Star on the Web. 29 September 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Blue Star's S.S. "Arandora Star"". One of The Luxury Five. Blue Star on the Web. 23 June 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Mummery & Butler 1999, pp. 88-98.

- 1 2 Taffrail, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Hague, Arnold. "Empire Strength". Ship Movements. Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ↑ Taffrail, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Taffrail, p. 41.

- 1 2 Taffrail, p. 42.

- ↑ Taffrail, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 3 Taffrail 1973, p. 43.

- ↑ Dunmore, Spenser (1999). In Great Waters. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-7710-2929-5.

just one torpedo left, which he believed to be faulty, an everyday problem at the time. Prien had already attempted to fire it

- 1 2 3 4 Taffrail 1973, p. 44.

- 1 2 Taffrail 1973, p. 45.

- ↑ Ian Hawkins, ed. (2008). Destroyer: An Anthology of First-hand Accounts of the War at Sea 1939–1945. London: Anova Books. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-84486-008-1.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (1983). Volume 6: Finest Hour, 1939–41. Winston S. Churchill. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0434291870.

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael (2008). Guarding Neutral Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-097-7.

- ↑ "S.S. "ARANDORA STAR" 1. The Colonsay Connection". The Colonsay Website. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ "After 69 years of families' pain over war-time tragedy, town's mayor says... WE'RE SORRY". Evening Gazette. 4 July 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ "Service marks 70th anniversary of ship tragedy". BBC Wales. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ↑ "Memorial garden to victims of Arandora sinking opens". The Herald. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

Sources and further reading

- Balestracci, Maria Serena (2008). Arandora Star: from Oblivion to Memory. Parma: Mup Publishers. The book, with both English and Italian texts, includes rare and previously unpublished material, such as pictures related to the rescue of the Arandora Star taken in 1940 by St. Laurent's crew.

- Gardner, N. (4 September 2005). "Tragic Waters: The Sinking of the Arandora Star". Hidden Europe. pp. 34–36.

- Gillman, Peter; Gillman, Leni (1980). Collar the Lot! How Britain Interned & Expelled its Wartime Refugees. Quartet Books. ISBN 0704334089. This book gives the wider context of the sinking, includes first-hand accounts from a number of Italian, German and British survivors, and provided the first full history of the sinking to be published after the Second World War.

- Miller, William H, Jr. Pictorial Encyclopedia of Ocean Liners, 1860–1994. Dover Maritime Books.

- Mitchell, W.H.; Sawyer, S.A. (1967). Cruising Ships. Merchant Ships of the World. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0356015041.

- Mummery, Brian; Butler, Ian (1999). Immingham and the Great Central Legacy (Images of England). Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0 7524 1714 2. This book includes several quayside photographs of the ship.

- Henry Taprell Dorling (1973). Blue Star Line at War, 1939–45. London: W. Foulsham & Co. pp. 9, 40–45. ISBN 0-572-00849-X.

External links

- ... And then came the Blitz

- Story of the sinking

- The Arandora Star

- "Blue Star's S.S. "Arandora Star"". One of The Luxury Five. Blue Star on the Web. 23 June 2013.

- Sinking of the Arandora Star: A Donegal Perspective

- Firsthand testimony about The lifeboat remains on Mull and summary of the dark side to the story

- The Tragedy of the Arandora Star

- Michael Kennedy, "Men that came in with the sea" which appeared in "History Ireland" in 2008.

- IWM Interview with survivor Nicola Cua

- IWM Interview with survivor Ivor Duxberry

- IWM Interview with survivor Gino Guarnieri

- IWM Interview with survivor Luigi Beschizza

- IWM Interview with survivor Ludwig Baruch

- Arandora Star victims: a supplement to the White Paper by Louis Eleazar Gutmann-Pelangen, c.1941, typescript testament by a man who had been interned with German and Austrian passengers on the SS Arandora Star.

Coordinates: 55°20′N 10°33′W / 55.333°N 10.550°W