Asymptotic gain model

The asymptotic gain model[1][2] (also known as the Rosenstark method[3]) is a representation of the gain of negative feedback amplifiers given by the asymptotic gain relation:

where is the return ratio with the input source disabled (equal to the negative of the loop gain in the case of a single-loop system composed of unilateral blocks), G∞ is the asymptotic gain and G0 is the direct transmission term. This form for the gain can provide intuitive insight into the circuit and often is easier to derive than a direct attack on the gain.

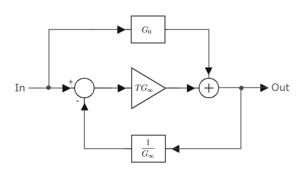

Figure 1 shows a block diagram that leads to the asymptotic gain expression. The asymptotic gain relation also can be expressed as a signal flow graph. See Figure 2. The asymptotic gain model is a special case of the extra element theorem.

Definition of terms

As follows directly from limiting cases of the gain expression, the asymptotic gain G∞ is simply the gain of the system when the return ratio approaches infinity:

while the direct transmission term G0 is the gain of the system when the return ratio is zero:

Advantages

- This model is useful because it completely characterizes feedback amplifiers, including loading effects and the bilateral properties of amplifiers and feedback networks.

- Often feedback amplifiers are designed such that the return ratio T is much greater than unity. In this case, and assuming the direct transmission term G0 is small (as it often is), the gain G of the system is approximately equal to the asymptotic gain G∞.

- The asymptotic gain is (usually) only a function of passive elements in a circuit, and can often be found by inspection.

- The feedback topology (series-series, series-shunt, etc.) need not be identified beforehand as the analysis is the same in all cases.

Implementation

Direct application of the model involves these steps:

- Select a dependent source in the circuit.

- Find the return ratio for that source.

- Find the gain G∞ directly from the circuit by replacing the circuit with one corresponding to T = ∞.

- Find the gain G0 directly from the circuit by replacing the circuit with one corresponding to T = 0.

- Substitute the values for T, G∞ and G0 into the asymptotic gain formula.

These steps can be implemented directly in SPICE using the small-signal circuit of hand analysis. In this approach the dependent sources of the devices are readily accessed. In contrast, for experimental measurements using real devices or SPICE simulations using numerically generated device models with inaccessible dependent sources, evaluating the return ratio requires special methods.

Connection with classical feedback theory

Classical feedback theory neglects feedforward (G0). If feedforward is dropped, the gain from the asymptotic gain model becomes

while in classical feedback theory, in terms of the open loop gain A, the gain with feedback (closed loop gain) is:

Comparison of the two expressions indicates the feedback factor βFB is:

while the open-loop gain is:

If the accuracy is adequate (usually it is), these formulas suggest an alternative evaluation of T: evaluate the open-loop gain and G∞ and use these expressions to find T. Often these two evaluations are easier than evaluation of T directly.

Examples

The steps in deriving the gain using the asymptotic gain formula are outlined below for two negative feedback amplifiers. The single transistor example shows how the method works in principle for a transconductance amplifier, while the second two-transistor example shows the approach to more complex cases using a current amplifier.

Single-stage transistor amplifier

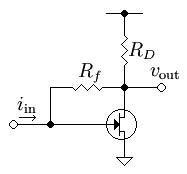

Consider the simple FET feedback amplifier in Figure 3. The aim is to find the low-frequency, open-circuit, transresistance gain of this circuit G = vout / iin using the asymptotic gain model.

The small-signal equivalent circuit is shown in Figure 4, where the transistor is replaced by its hybrid-pi model.

Return ratio

It is most straightforward to begin by finding the return ratio T, because G0 and G∞ are defined as limiting forms of the gain as T tends to either zero or infinity. To take these limits, it is necessary to know what parameters T depends upon. There is only one dependent source in this circuit, so as a starting point the return ratio related to this source is determined as outlined in the article on return ratio.

The return ratio is found using Figure 5. In Figure 5, the input current source is set to zero, By cutting the dependent source out of the output side of the circuit, and short-circuiting its terminals, the output side of the circuit is isolated from the input and the feedback loop is broken. A test current it replaces the dependent source. Then the return current generated in the dependent source by the test current is found. The return ratio is then T = −ir / it. Using this method, and noticing that RD is in parallel with rO, T is determined as:

where the approximation is accurate in the common case where rO >> RD. With this relationship it is clear that the limits T → 0, or ∞ are realized if we let transconductance gm → 0, or ∞.[5]

Asymptotic gain

Finding the asymptotic gain G∞ provides insight, and usually can be done by inspection. To find G∞ we let gm → ∞ and find the resulting gain. The drain current, iD = gm vGS, must be finite. Hence, as gm approaches infinity, vGS also must approach zero. As the source is grounded, vGS = 0 implies vG = 0 as well.[6] With vG = 0 and the fact that all the input current flows through Rf (as the FET has an infinite input impedance), the output voltage is simply −iin Rf. Hence

Alternatively G∞ is the gain found by replacing the transistor by an ideal amplifier with infinite gain - a nullor.[7]

Direct feedthrough

To find the direct feedthrough we simply let gm → 0 and compute the resulting gain. The currents through Rf and the parallel combination of RD || rO must therefore be the same and equal to iin. The output voltage is therefore iin (RD || rO).

Hence

where the approximation is accurate in the common case where rO >> RD.

Overall gain

The overall transresistance gain of this amplifier is therefore:

Examining this equation, it appears to be advantageous to make RD large in order make the overall gain approach the asymptotic gain, which makes the gain insensitive to amplifier parameters (gm and RD). In addition, a large first term reduces the importance of the direct feedthrough factor, which degrades the amplifier. One way to increase RD is to replace this resistor by an active load, for example, a current mirror.

Two-stage transistor amplifier

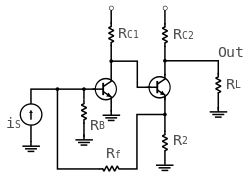

Figure 6 shows a two-transistor amplifier with a feedback resistor Rf. This amplifier is often referred to as a shunt-series feedback amplifier, and analyzed on the basis that resistor R2 is in series with the output and samples output current, while Rf is in shunt (parallel) with the input and subtracts from the input current. See the article on negative feedback amplifier and references by Meyer or Sedra.[8][9] That is, the amplifier uses current feedback. It frequently is ambiguous just what type of feedback is involved in an amplifier, and the asymptotic gain approach has the advantage/disadvantage that it works whether or not you understand the circuit.

Figure 6 indicates the output node, but does not indicate the choice of output variable. In what follows, the output variable is selected as the short-circuit current of the amplifier, that is, the collector current of the output transistor. Other choices for output are discussed later.

To implement the asymptotic gain model, the dependent source associated with either transistor can be used. Here the first transistor is chosen.

Return ratio

The circuit to determine the return ratio is shown in the top panel of Figure 7. Labels show the currents in the various branches as found using a combination of Ohm's law and Kirchhoff's laws. Resistor R1 = RB // rπ1 and R3 = RC2 // RL. KVL from the ground of R1 to the ground of R2 provides:

KVL provides the collector voltage at the top of RC as

Finally, KCL at this collector provides

Substituting the first equation into the second and the second into the third, the return ratio is found as

Gain G0 with T = 0

The circuit to determine G0 is shown in the center panel of Figure 7. In Figure 7, the output variable is the output current βiB (the short-circuit load current), which leads to the short-circuit current gain of the amplifier, namely βiB / iS:

Using Ohm's law, the voltage at the top of R1 is found as

or, rearranging terms,

Using KCL at the top of R2:

Emitter voltage vE already is known in terms of iB from the diagram of Figure 7. Substituting the second equation in the first, iB is determined in terms of iS alone, and G0 becomes:

Gain G0 represents feedforward through the feedback network, and commonly is negligible.

Gain G∞ with T → ∞

The circuit to determine G∞ is shown in the bottom panel of Figure 7. The introduction of the ideal op amp (a nullor) in this circuit is explained as follows. When T → ∞, the gain of the amplifier goes to infinity as well, and in such a case the differential voltage driving the amplifier (the voltage across the input transistor rπ1) is driven to zero and (according to Ohm's law when there is no voltage) it draws no input current. On the other hand, the output current and output voltage are whatever the circuit demands. This behavior is like a nullor, so a nullor can be introduced to represent the infinite gain transistor.

The current gain is read directly off the schematic:

Comparison with classical feedback theory

Using the classical model, the feed-forward is neglected and the feedback factor βFB is (assuming transistor β >> 1):

and the open-loop gain A is:

Overall gain

The above expressions can be substituted into the asymptotic gain model equation to find the overall gain G. The resulting gain is the current gain of the amplifier with a short-circuit load.

Gain using alternative output variables

In the amplifier of Figure 6, RL and RC2 are in parallel. To obtain the transresistance gain, say Aρ, that is, the gain using voltage as output variable, the short-circuit current gain G is multiplied by RC2 // RL in accordance with Ohm's law:

The open-circuit voltage gain is found from Aρ by setting RL → ∞.

To obtain the current gain when load current iL in load resistor RL is the output variable, say Ai, the formula for current division is used: iL = iout × RC2 / ( RC2 + RL ) and the short-circuit current gain G is multiplied by this loading factor:

Of course, the short-circuit current gain is recovered by setting RL = 0 Ω.

References and notes

- ↑ Middlebrook, RD: Design-oriented analysis of feedback amplifiers; Proc. of National Electronics Conference, Vol. XX, Oct. 1964, pp. 1–4

- ↑ Rosenstark, Sol (1986). Feedback amplifier principles. NY: Collier Macmillan. p. 15. ISBN 0-02-947810-3.

- ↑ Palumbo, Gaetano & Salvatore Pennisi (2002). Feedback amplifiers: theory and design. Boston/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic. pp. §3.3 pp. 69–72. ISBN 0-7923-7643-9.

- ↑ Paul R. Gray, Hurst P J Lewis S H & Meyer RG (2001). Analysis and design of analog integrated circuits (Fourth ed.). New York: Wiley. Figure 8.42 p. 604. ISBN 0-471-32168-0.

- ↑ Although changing RD // rO also could force the return ratio limits, these resistor values affect other aspects of the circuit as well. It is the control parameter of the dependent source that must be varied because it affects only the dependent source.

- ↑ Because the input voltage vGS approaches zero as the return ratio gets larger, the amplifier input impedance also tends to zero, which means in turn (because of current division) that the amplifier works best if the input signal is a current. If a Norton source is used, rather than an ideal current source, the formal equations derived for T will be the same as for a Thévenin voltage source. Note that in the case of input current, G∞ is a transresistance gain.

- ↑ Verhoeven CJ, van Staveren A, Monna GL, Kouwenhoven MH & Yildiz E (2003). Structured electronic design: negative-feedback amplifiers. Boston/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic. pp. §2.3 – §2.5 pp. 34–40. ISBN 1-4020-7590-1.

- ↑ P R Gray; P J Hurst; S H Lewis & R G Meyer (2001). Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits (Fourth ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 586–587. ISBN 0-471-32168-0.

- ↑ A. S. Sedra & K.C. Smith (2004). Microelectronic Circuits (Fifth ed.). New York: Oxford. Example 8.4, pp. 825–829 and PSpice simulation pp. 855–859. ISBN 0-19-514251-9.

See also

- Blackman's theorem

- Extra element theorem

- Mason's gain formula

- Feedback amplifiers

- Return ratio

- Signal-flow graph