River Little Ouse

| River Little Ouse | |

| River | |

| The river north of Lakenheath | |

| Country | England |

|---|---|

| Counties | Norfolk, Suffolk |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Black Bourn, Lakenheath Lode |

| - right | River Thet |

| Source | |

| - location | Thelnetham, Norfolk/Suffolk border |

| - elevation | 25 m (82 ft) |

| - coordinates | GB-ENG 52°22′16″N 0°59′39″E / 52.37124°N 0.99405°E |

| Mouth | Brandon Creek |

| - location | Littleport, Cambridgeshire |

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| - coordinates | GB-ENG 52°30′04″N 0°22′01″E / 52.50121°N 0.36704°ECoordinates: GB-ENG 52°30′04″N 0°22′01″E / 52.50121°N 0.36704°E |

| Length | 37 mi (60 km) |

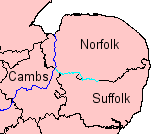

Little Ouse (light blue) and Great Ouse (dark) | |

The River Little Ouse is a river in the east of England, a tributary of the River Great Ouse. For much of its length it defines the boundary between Norfolk and Suffolk.

It rises east of Thelnetham, very close to the source of the River Waveney - which flows eastwards while the Little Ouse flows west. The village with the curious name of Blo' Norton owes this name to the river - it was earlier known as Norton Bell-'eau, from being situated near this 'fair stream'. In this area the river creates a number of important wetland areas such as at Blo' Norton and Thelnetham Fen and areas managed by the Little Ouse Headwaters Project.[1] The course continues through Rushford, Thetford, Brandon, and Hockwold before the river joins the Great Ouse north of Littleport in Cambridgeshire. The total length is about 37 miles (60 km).

The river is currently navigable from the Great Ouse to a point 2 miles (3.2 km) above Brandon.

Its origin

The most distinctive feature of the headwaters of the Little Ouse and the Waveney is the valley in which they flow; the Little Ouse westwards and the Waveney, eastwards. It has a broad, fenny bottom, lies at an altitude of up to 85 feet (26 m) and both rivers rise in the fen alongside the B1113 road, between South Lopham and Redgrave. (See map). The explanation of this oddity is that the valley was formed, not by these rivers but by water spilling from Lake Fenland. This was a periglacial lake of the Devensian glacial, fifteen or twenty thousand years ago. The ice sheet closed the natural drainage from the Vale of Pickering, the Humber and The Wash so that a lake of a complex shape formed in the Vale of Pickering, the Yorkshire Ouse valley, the lower Trent valley and the Fenland basin. This valley was its spillway into the southern North Sea basin, thence to the English Channel basin, which at the time, contained no sea.

The downstream end of the Little Ouse has changed much over the centuries. In the Fens and Norfolk Marshland, it was quite possible for the course of a river to change as the result of a flooding episode so it is not surprising to find that the Great Ouse used to enter The Wash by way of the Old Croft River, the Wellstream and Wisbech (the Ouse beach). The modern lower Great Ouse was then the lower part of the Little Ouse. On this occasion, the change was artificial. The 17th century drainers under Cornelius Vermuyden dug the Old Bedford River between the Great Ouse at Earith and what had hitherto been the Little Ouse at Denver. A link was made for the Great Ouse between Littleport 1 and the Little Ouse at Brandon Creek (See map) and both the drainage and the navigation were directed towards King's Lynn rather than Wisbech.

Flood precautions

The Environment Agency has designated the section from Thetford to Brandon, where it flows through the afforested Breckland, as a Flood Warning Area.[2]

The lower part of the river crosses over the Cut-off Channel in a concrete aqueduct. The Channel is a 25-mile (40 km) drain which runs from Barton Mills to Denver along the south-eastern edge of the Fens, and was constructed in the 1950s and 1960s. During times of flood it carries the head waters of the River Lark, the River Wissey and the Little Ouse to Denver Sluice.[3] On its south side are two sluices, so that flood water from the upper river can be diverted into the cut-off channel and the section between there and the Great Ouse isolated. The flood banks on this lower section are up to half a mile wide so that the meandering river will form a large lake.

Nearer the mouth of the river, the Brandon Engine was the main outlet for the drainage of the northern half of Burnt Fen from 1830[4] until 1958. The original steam engine was replaced in 1892, by a new engine that could pump 75 tons per minute.[5] That engine was replaced by a 250 horse power oil engine in late 1925, supplied by Blackstone and Company, which drove a 42-inch (110 cm) Gwynne rotary pump. The pump could discharge 150 tons per minute against a head of 18 feet (5.5 m),[6] and lasted for 30 years. When a replacement was considered in the 1950s, the Commissioners of the Burnt Fen were faced with the problem that the White House Drain which supplied it had become bigger and more unstable as the ground surface had shrunk, and the engine sat at the top of a hill, rather than at the lowest point on the northern Fen. Consequently, a new electric pumping station was constructed at Whitehall on the River Great Ouse, the flow in the drain reversed, and the pumping station decommissioned.[7]

Navigation

River Little Ouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The river is currently navigable for 16.6 miles (26.7 km) from its junction with the River Great Ouse to Santon Downham bridge.[8] There are references to its use by boats carrying goods to Brandon as early as the 13th century, and barges are known to have reached Thetford, some 6 miles (9.7 km) beyond Santon Downham when the river was tidal.[9] Stone from Barnack, used in the construction of Thetford Priory in the 12th century, was almost certainly moved along the river, and improvements to the channel were authorised by the Commissioners of Sewers as early as 1575. Further documentary evidence confirms that it was navigable as far as Thetford in 1664.[10]

However, water levels dropped when Denver Sluice was built on the River Great Ouse. An Act of Parliament authorised the Corporation of Thetford to make improvements to the river in 1670, but they were unable to carry out the work, and so the Rt Hon Henry, Earl of Arlington made the improvements, and was assigned the tolls as a result.[10] A series of staunches were built, to hold back the water and raise the levels, but they were too far apart to be effective.[11] The rights of the navigation were given to Thetford Corporation by Henry's daughter Isabella in 1696, and the Corporation had to build a new staunch near Thetford in 1742, in order to maintain water levels in the town.[12]

By 1750, disputes were arising, since all the original Commissioners were dead, and they had failed to appoint replacements. A new Act of Parliament was sought and obtained in 1751, which appointed new Commissioners. Immediately, Thetford Corporation made improvements to the river, constructing staunches at Thetford, Thetford Middle, Turfpool, Croxton, Santon, Brandon and Sheepwash. An eighth staunch was built later at Crosswater, where Lakenheath Lode joins the river. A further Act was obtained in 1789, which regularised the collection of tolls on the whole river by Thetford Corporation. They rebuilt the seven staunches between 1827 and 1835, and the £955 of income received from the navigation in 1833 accounted for over 90 per cent of the total income of the Corporation.[13]

The 1770s saw a grand plan to build a canal from the Little Ouse at Thetford to the River Stort at Bishops Stortford. With a spur to Cambridge, this would have enabled goods to reach London by canal from much of East Anglia. Although the capital cost could not be justified, it was not until the 1850s and the advent of the railways that the scheme was finally abandoned.[11]

Tolls reached a record £1,728 in 1845, when over 15,000 tonnes of coal were carried, but the arrival of the railways, in the form of a line from Norwich to Brandon, and an extension of the Eastern Counties Railway from Newport to Brandon, both opened on the same day in 1845, started the rapid decline of the navigation. Tolls had fallen to £439 by 1849. The tolls were leased to private individuals from 1850, but an attempt to transfer £320 to the Council finance committee from the navigation in 1859 resulted in nearly a year of legal wrangling, and ultimately the money was repaid in 1860.[14] The state of the navigation declined steadily, although there was still commercial traffic, and a 25-foot (7.6 m) paddle steamer ran trips to Cambridge and around the local waterways in the 1880s.[15]

Repairs were again necessary in the 1890s, but with no funds available, the navigation committee asked Fisons, who ran a 50-foot (15 m) screw tug called Speedwell to tow lighters to King's Lynn, for an advance on their tolls to fund the work. This arrangement continued, and kept the navigation open for some years.[16] When Henry de Salis visited it in 1904, he reported that most of the staunches were out of order, and that it was in poor condition.[17] The Bedford Level Commissioners kept the weed removed from the lower section, and the South Level Commissioners maintained Crosswater Staunch, but commercial traffic had ceased by the start of the First World War. Responsibility for the river passed to the Great Ouse Catchment Board with the passing of the Land Drainage Act 1930, and they removed the staunches, replacing those at Thetford and at Brandon with sluices.[18] Responsibility changed again with the formation of the Environment Agency in 1995.

The navigable river is mainly on the same level, with a single lock, which was opened in 1995, at Brandon just a short distance from Brandon bridge. The lock is 13 feet (4.0 m) wide but only 39 feet (12 m) long, and so is not suitable for many narrow boats, although boats up to 79 feet (24 m) long can be turned just below the lock, which is less than 0.5 miles (0.80 km) from Brandon village.[19]

There is a campaign to re-open the river for navigation to Thetford, and the Environment Agency commissioned consultants in 2003 to look at the feasibility of such a project. The report suggested that four locks would be required on this section.[20] The head of navigation was effectively extended in 2008 when the 2.5-mile (4.0 km) section from Brandon Bridge to Santon Downham was made more accessible to boaters by the construction of moorings just below Santon Downham bridge, which are now managed by the Great Ouse Boating Association. Beyond the bridge the river is only accessible to canoes and dingies, due to the presence of rocks on the river bed.[8]

Points of interest

Immediately upstream of Nuns Bridges, Thetford, the river was widened to form Thetford swimming pool, which remained in use until the 1970s when an indoor pool was built. The steps and rail of the pool are still visible. Immediately upstream of the swimming pool, the river runs through Nunnery Lakes Reserve, a bird reserve owned and operated by the British Trust for Ornithology, whose headquarters are in the adjacent Nunnery buildings.[21]

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jn with River Great Ouse | 52°30′04″N 0°22′00″E / 52.5011°N 0.3668°E | TL607918 | |

| Lakenheath Lode | 52°26′33″N 0°27′19″E / 52.4426°N 0.4554°E | TL669855 | |

| Cut-off Channel sluices | 52°27′13″N 0°32′49″E / 52.4537°N 0.5469°E | TL731870 | |

| Brandon Lock | 52°26′57″N 0°36′57″E / 52.4493°N 0.6157°E | TL778867 | |

| Santon Downham | 52°27′31″N 0°40′24″E / 52.4586°N 0.6732°E | TL817878 | Limit of navigation |

| Abbey Heath Weir | 52°25′34″N 0°43′15″E / 52.4260°N 0.7209°E | TL850843 | |

| Jn with River Thet | 52°24′48″N 0°44′48″E / 52.4133°N 0.7468°E | TL869830 | |

| Jn with The Black Bourn | 52°23′11″N 0°46′24″E / 52.3863°N 0.7732°E | TL888800 | |

| Source of river | 52°22′16″N 0°59′39″E / 52.3712°N 0.9942°E | TM039790 |

Bibliography

- Beckett, John (1983). Urgent Hour: Drainage of the Burnt Fen District in the South Level of the Fens, 1760-1981. Ely Local History Publication Board. ISBN 978-0904463880.

- Blair, Andrew Hunter (2006). The River Great Ouse and tributaries. Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85288-943-5.

- Boyes, John; Russell, Ronald (1977). The Canals of Eastern England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-7415-3.

- Thirsk, Joan (2002). Rural England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860619-2.

See also

References

- ↑ Blo' Norton and Thelnetham Fen, SSSI citation, Natural England. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

- ↑ Environment Agency "Flood Warnings FWA Detail" Check

|url=value (help). Retrieved 25 April 2009. - ↑ Thirsk 2002

- ↑ Beckett 1983, p. 22

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 37–38

- ↑ Beckett 1983, pp. 42–43

- 1 2 "Easterling, The Journal of the EAWA". East Anglian Waterways Association. October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Blair 2006, pp. 72–73

- 1 2 Boyes & Russell 1977, p. 183

- 1 2 Blair 2006, p. 73

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, p. 184

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 184–185

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 185–187

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 187–188

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, p. 188

- ↑ Bradshaw's Canals & Navigable Rivers (1904)

- ↑ Boyes & Russell 1977, pp. 188–189

- ↑ Blair 2006, p. 78

- ↑ "Little Ouse Navigation". Inland Waterways Association. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ Nunnery Lakes Reserve - a visitor leaflet produced by the BTO

Footnote

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Little Ouse. |

- Note 1: See map The old, winding course of the Great Ouse was from the bottom of the map, along the green-dotted footpath, just south of the roundabout, along the Holmes River, westwards through the northern fringe of Littleport and northwards between the two brown 0 metre contour lines, until it passed out of the top of the map.