Circular buffer

A circular buffer, circular queue, cyclic buffer or ring buffer is a data structure that uses a single, fixed-size buffer as if it were connected end-to-end. This structure lends itself easily to buffering data streams.

Uses

The useful property of a circular buffer is that it does not need to have its elements shuffled around when one is consumed. (If a non-circular buffer were used then it would be necessary to shift all elements when one is consumed.) In other words, the circular buffer is well-suited as a FIFO buffer while a standard, non-circular buffer is well suited as a LIFO buffer.

Circular buffering makes a good implementation strategy for a queue that has fixed maximum size. Should a maximum size be adopted for a queue, then a circular buffer is a completely ideal implementation; all queue operations are constant time. However, expanding a circular buffer requires shifting memory, which is comparatively costly. For arbitrarily expanding queues, a linked list approach may be preferred instead.

In some situations, overwriting circular buffer can be used, e.g. in multimedia. If the buffer is used as the bounded buffer in the producer-consumer problem then it is probably desired for the producer (e.g., an audio generator) to overwrite old data if the consumer (e.g., the sound card) is unable to momentarily keep up. Also, the LZ77 family of lossless data compression algorithms operates on the assumption that strings seen more recently in a data stream are more likely to occur soon in the stream. Implementations store the most recent data in a circular buffer.

How it works

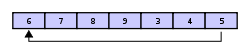

A circular buffer first starts empty and of some predefined length. For example, this is a 7-element buffer:

Assume that a 1 is written into the middle of the buffer (exact starting location does not matter in a circular buffer):

Then assume that two more elements are added — 2 & 3 — which get appended after the 1:

If two elements are then removed from the buffer, the oldest values inside the buffer are removed. The two elements removed, in this case, are 1 & 2, leaving the buffer with just a 3:

If the buffer has 7 elements then it is completely full:

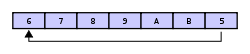

A consequence of the circular buffer is that when it is full and a subsequent write is performed, then it starts overwriting the oldest data. In this case, two more elements — A & B — are added and they overwrite the 3 & 4:

Alternatively, the routines that manage the buffer could prevent overwriting the data and return an error or raise an exception. Whether or not data is overwritten is up to the semantics of the buffer routines or the application using the circular buffer.

Finally, if two elements are now removed then what would be returned is not 3 & 4 but 5 & 6 because A & B overwrote the 3 & the 4 yielding the buffer with:

Circular buffer mechanics

A circular buffer can be implemented using four pointers, or two pointers and two integers:

- buffer start in memory

- buffer end in memory, or buffer capacity

- start of valid data (index or pointer)

- end of valid data (index or pointer), or amount of data currently in the buffer (integer)

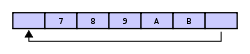

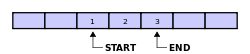

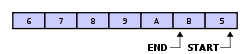

This image shows a partially full buffer:

This image shows a full buffer with four elements (numbers 1 through 4) having been overwritten:

When an element is overwritten, the start pointer is incremented to the next element.

In the pointer-based implementation strategy, the buffer's full or empty state can be resolved from the start and end indexes. When they are equal, the buffer is empty, and when the start is one greater than the end, the buffer is full.[1] When the buffer is instead designed to track the number of inserted elements n, checking for emptiness means checking n = 0 and checking for fullness means checking whether n equals the capacity.[2]

Optimization

A circular-buffer implementation may be optimized by mapping the underlying buffer to two contiguous regions of virtual memory. (Naturally, the underlying buffer‘s length must then equal some multiple of the system’s page size.) Reading from and writing to the circular buffer may then be carried out with greater efficiency by means of direct memory access; those accesses which fall beyond the end of the first virtual-memory region will automatically wrap around to the beginning of the underlying buffer. When the read offset is advanced into the second virtual-memory region, both offsets—read and write—are decremented by the length of the underlying buffer.[1]

Fixed-length-element and contiguous-block circular buffer

Perhaps the most common version of the circular buffer uses 8-bit bytes as elements.

Some implementations of the circular buffer use fixed-length elements that are bigger than 8-bit bytes—16-bit integers for audio buffers, 53-byte ATM cells for telecom buffers, etc. Each item is contiguous and has the correct data alignment, so software reading and writing these values can be faster than software that handles non-contiguous and non-aligned values.

Ping-pong buffering can be considered a very specialized circular buffer with exactly two large fixed-length elements.

The Bip Buffer (bipartite buffer) is very similar to a circular buffer, except it always returns contiguous blocks which can be variable length. This offers nearly all the efficiency advantages of a circular buffer while maintaining the ability for the buffer to be used in APIs that only accept contiguous blocks.[1]

Fixed-sized compressed circular buffers use an alternative indexing strategy based on elementary number theory to maintain a fixed-sized compressed representation of the entire data sequence.[3]

External links

- 1 2 3 Simon Cooke (2003), "The Bip Buffer - The Circular Buffer with a Twist"

- ↑ Morin, Pat. "ArrayQueue: An Array-Based Queue". Open Data Structures (in pseudocode). Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ↑ John C. Gunther. 2014. Algorithm 938: Compressing circular buffers. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 40, 2, Article 17 (March 2014)

- CircularBuffer at the Portland Pattern Repository

- Boost: Templated Circular Buffer Container

- http://www.dspguide.com/ch28/2.htm