Reed Painter

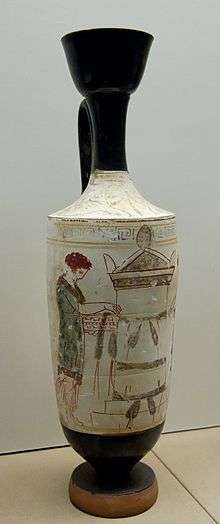

The Reed Painter (fl. 420s–410s BC) is an anonymous Greek vase painter of white-ground lekythoi, a type of vessel for containing oil often left as grave offerings. Works are attributed to either the "Reed Painter" or his atelier.

The vessels of the Reed Painter are typical of white-ground lekythoi in that they often focus on real people, in contrast to the earlier black-figure tradition that featured scenes of mythical figures pertaining to Dionysiac cult.[1] The purpose of the lekythos is often reflected in its subject matter. This artist's most common theme is a scene depicting a visit to a tomb. The figures, usually a woman bringing offerings or a youth leaning on a spear, display quiet dignity rather than emotion. The tomb, topped by a pediment, provides important evidence for funerary monuments in Attica at the time. The artist takes his name from his characteristic use of reeds in the landscape, particularly in depictions of Charon, the ferryman of the dead in Greek mythology.[2]

A lekythos by the Reed Painter is one of only a few white-figure examples that depict a horseman at a tomb; unusually, the youth sits at the tomb with his horse rather than riding it.[3] He may be an ephebe in training for the cavalry, as he wears the black cloak (chlamys) that was characteristic attire for the Athenian ephebe at certain processions and festivals. He also wears a helmet in the shape of the petasos, a hat typically worn by travelers, the metal version of which appears on Athenian reliefs and is known from archaeology. He carries two hunting spears, and not the kamax, the long thin spear principally used by Greek cavalry.[4]

Around the turn of the 20th–21st centuries, a number of the artist's lekythoi were discovered in a mass burial of plague victims in Athens.[5] Work from the atelier of the Reed Painter is concentrated in Attica, though a few examples have been found as exports to Gela and Corinth.[6]

The Reed Painter worked in true white-ground technique, in which polychrome figures are outlined on the white ground, first in a dilute brown glaze and then in a more-fluid matt black or red. Women's skin was painted white on white, with solid colors on garments. The colors — including bright red, yellow, purple, blue, and green — were added after firing.[7] The unstable pigments have flaked away and often left figures on surviving vases with the appearance of nudity when they were intended to be clothed.[8]

References

- ↑ Lawrence A. Tritle, A New History of the Peloponnesian War (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 49.

- ↑ Peter Connor and Heather Jackson, A Catalogue of Greek Vases in the Collection of the University of Melbourne at the Ian Potter Museum of Art (University of Melbourne, 2000), p. 159.

- ↑ John H. Oakley, "White Lekythoi from Gela," in Ta Attika: Attic Figured Vases from Gela («L'Erma» di Bretschneider, 2003), p. 212.

- ↑ Nicholas Sekunda, The Ancient Greeks (Osprey Publishing, 1986, 2005), p. 19.

- ↑ Oakley, "White Lekythoi from Gela," p. 212.

- ↑ Maria Cecilia d'Ercole, "Figures hybrides d l'identité: Le cas de l'Adriatique préromaine," in Identités ethniques dans le monde grec antique (Presses Universitaires du Mirall, 2007), p. 172.

- ↑ Connor and Jackson, A Catalogue of Greek Vases, p. 157.

- ↑ Donald White et al., The Ancient Greek World: The Rodney S. Young Gallery (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1995), p. 35.