Ramadan

| رمضان Ramadan | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Observed by | Muslims |

| Type | Religious |

| Celebrations | Community iftars and Community prayers |

| Observances | |

| Begins | 1 Ramadan |

| Ends | 29, or 30 Ramadan |

| Date | Variable (follows the Islamic lunar calendar) |

| 2016 date | 6 June – 5 July (Umm al-Qura)[1] |

| 2017 date | 27 May – 24 June[1] |

| 2018 date | 16 May – 14 June[1] |

| Frequency | every 12 moons (lunar months) |

| Related to | Eid al-Fitr, Laylat al-Qadr |

Ramadan (/ˌræməˈdɑːn/; Arabic: رمضان Ramaḍān, IPA: [ramaˈdˤaːn];[note 1] also romanized as Ramazan, Ramadhan, or Ramathan) is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar,[2] and is observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting to commemorate the first revelation of the Quran to Muhammad according to Islamic belief.[3][4] This annual observance is regarded as one of the Five Pillars of Islam.[5] The month lasts 29–30 days based on the visual sightings of the crescent moon, according to numerous biographical accounts compiled in the hadiths.[6][7]

The word Ramadan comes from the Arabic root ramiḍa or ar-ramaḍ, which means scorching heat or dryness.[8] Fasting is fardh (obligatory) for adult Muslims, except those who are suffering from an illness, travelling, are elderly, pregnant, breastfeeding, diabetic or going through menstrual bleeding.[9] Fasting the month of Ramadan was made obligatory (wājib) during the month of Sha'aban, in the second year after the Muslims migrated from Mecca to Medina. Fatwas have been issued declaring that Muslims who live in regions with a natural phenomenon such as the midnight sun or polar night should follow the timetable of Mecca.[10]

While fasting from dawn until sunset, Muslims refrain from consuming food, drinking liquids, smoking, and engaging in sexual relations. Muslims are also instructed to refrain from sinful behavior that may negate the reward of fasting, such as false speech (insulting, backbiting, cursing, lying, etc.) and fighting.[11] Food and drinks are served daily, before dawn and after sunset.[12][13] Spiritual rewards (thawab) for fasting are also believed to be multiplied within the month of Ramadan.[14] Fasting for Muslims during Ramadan typically includes the increased offering of salat (prayers) and recitation of the Quran.[15][16]

History

Chapter 2, Verse 185, of the Quran states:

The month of Ramadan is that in which was revealed the Quran; a guidance for mankind, and clear proofs of the guidance, and the criterion (of right and wrong). And whosoever of you is present, let him fast the month, and whosoever of you is sick or on a journey, a number of other days. Allah desires for you ease; He desires not hardship for you; and that you should complete the period, and that you should magnify Allah for having guided you, and that perhaps you may be thankful.[Quran 2:185]

It is believed that the Quran was first revealed to Muhammad during the month of Ramadan which has been referred to as the "best of times". The first revelation was sent down on Laylat al-Qadr (The night of Power) which is one of the five odd nights of the last ten days of Ramadan.[17] According to hadith, all holy scriptures were sent down during Ramadan. The tablets of Ibrahim, the Torah, the Psalms, the Gospel and the Quran were sent down on 1st, 6th, 12th, 13th[note 2] and 24th Ramadan respectively.[18]

According to the Quran, fasting was also obligatory for prior nations, and is a way to attain taqwa, fear of God.[19][Quran 2:183] God proclaimed to Muhammad that fasting for His sake was not a new innovation in monotheism, but rather an obligation practiced by those truly devoted to the oneness of God.[20] The pagans of Mecca also fasted, but only on tenth day of Muharram to expiate sins and avoid droughts.[21]

The ruling to observe fasting during Ramadan was sent down 18 months after Hijra, during the month of Sha'aban in the second year of Hijra in 624 CE.[18]

Abu Zanad, an Arabic writer from Iraq who lived after the founding of Islam, in around 747 CE, wrote that at least one Mandaean community located in al-Jazira (modern northern Iraq) observed Ramadan before converting to Islam.[22]

According to Philip Jenkins, Ramadan comes "from the strict Lenten discipline of the Syrian churches".[23] However, this suggestion is based on the orientalist idea that the Qur'an itself has Syrian origins, which was refuted by Muslim academics such as M. Al-Azami.[24]

Important dates

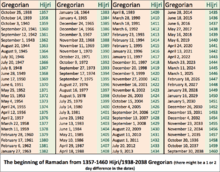

The beginning and end of Ramadan are determined by the lunar Islamic calendar.

Beginning

Hilāl (the crescent) is typically a day (or more) after the astronomical new moon. Since the new moon marks the beginning of the new month, Muslims can usually safely estimate the beginning of Ramadan.[25] However, to many Muslims, this is not in accordance with authenticated Hadiths stating that visual confirmation per region is recommended. The consistent variations of a day have existed since the time of Muhammad.[26]

Night of Power

Laylat al-Qadr, which in Arabic means "the night of power" or "the night of decree", is considered the holiest night of the year.[27][28] This is the night in which Muslims believe the first revelation of the Quran was sent down to Muhammad stating that this night was "better than one thousand months [of proper worship], as stated in Chapter 97:3 of the Qu'ran.

Also, generally, Laylat al-Qadr is believed to have occurred on an odd-numbered night during the last ten days of Ramadan, i.e., the night of the 21st, 23rd, 25th, 27th or 29th. The Dawoodi Bohra Community believe that the 23rd night is laylat al Qadr.[29] [30]

End

The holiday of Eid al-Fitr (Arabic:عيد الفطر) marks the end of Ramadan and the beginning of the next lunar month, Shawwal. This first day of the following month is declared after another crescent new moon has been sighted or the completion of 30 days of fasting if no visual sighting is possible due to weather conditions. This first day of Shawwal is called Eid al-Fitr. Eid al-Fitr may also be a reference towards the festive nature of having endured the month of fasting successfully and returning to the more natural disposition (fitra) of being able to eat, drink and resume intimacy with spouses during the day.[31]

Religious practices

The common practice during Ramadan is fasting from dawn to sunset. The pre-dawn meal before the fast is called the suhur, while the meal at sunset that breaks the fast is the iftar. Considering the high diversity of the global Muslim population, it is impossible to describe typical suhur or iftar meals.

Muslims also engage in increased prayer and charity during Ramadan. Ramadan is also a month where Muslims try to practice increased self-discipline. This is motivated by the Hadith, especially in Al-Bukhari[32] and Muslim,[33] that "When Ramadan arrives, the gates of Paradise are opened and the gates of hell are locked up and devils are put in chains."[34]

Fasting

Ramadan is a time of spiritual reflection, improvement and increased devotion and worship. Muslims are expected to put more effort into following the teachings of Islam. The fast (sawm) begins at dawn and ends at sunset. In addition to abstaining from eating and drinking, Muslims also increase restraint, such as abstaining from sexual relations and generally sinful speech and behavior. The act of fasting is said to redirect the heart away from worldly activities, its purpose being to cleanse the soul by freeing it from harmful impurities. Ramadan also teaches Muslims how to better practice self-discipline, self-control,[35] sacrifice, and empathy for those who are less fortunate; thus encouraging actions of generosity and compulsory charity (zakat).[36]

It becomes compulsory for Muslims to start fasting when they reach puberty, so long as they are healthy and sane, and have no disabilities or illnesses. Many children endeavour to complete as many fasts as possible as practice for later life.

Exemptions to fasting are travel, menstruation, severe illness, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. However, many Muslims with medical conditions insist on fasting to satisfy their spiritual needs, although it is not recommended by the hadith. Professionals should closely monitor such individuals who decide to persist with fasting.[37] Those who were unable to fast still must make up the days missed later.[38]

Suhur

Each day, before dawn, Muslims observe a pre-fast meal called the suhur. After stopping a short time before dawn, Muslims begin the first prayer of the day, Fajr.[39][40] At sunset, families hasten for the fast-breaking meal known as iftar.

Iftar

In the evening, dates are usually the first food to break the fast; according to tradition, Muhammad broke fast with three dates. Following that, Muslims generally adjourn for the Maghrib prayer, the fourth of the five daily prayers, after which the main meal is served.[41]

Social gatherings, many times in a buffet style, are frequent at iftar. Traditional dishes are often highlighted, including traditional desserts, and particularly those made only during Ramadan. Water is usually the beverage of choice, but juice and milk are also often available, as are soft drinks and caffeinated beverages.[37]

In the Middle East, the iftar meal consists of water, juices, dates, salads and appetizers, one or more main dishes, and various kinds of desserts. Usually, the dessert is the most important part during iftar. Typical main dishes are lamb stewed with wheat berries, lamb kebabs with grilled vegetables, or roast chicken served with chickpea-studded rice pilaf. A rich dessert, such as luqaimat, baklava or kunafeh (a buttery, syrup-sweetened kadaifi noodle pastry filled with cheese), concludes the meal.[42]

Over time, iftar has grown into banquet festivals. This is a time of fellowship with families, friends and surrounding communities, but may also occupy larger spaces at masjid or banquet halls for 100 or more diners.[43]

Charity

Charity is very important in Islam, and even more so during Ramadan. Zakāt, often translated as "the poor-rate", is obligatory as one of the pillars of Islam; a fixed percentage of the person's savings is required to be given to the poor. Sadaqah is voluntary charity in giving above and beyond what is required from the obligation of zakāt. In Islam, all good deeds are more handsomely rewarded during Ramadan than in any other month of the year. Consequently, many will choose this time to give a larger portion, if not all, of the zakāt that they are obligated to give. In addition, many will also use this time to give a larger portion of sadaqah in order to maximize the reward that will await them at the Last Judgment.

Nightly prayers

Tarawih (Arabic: تراويح) refers to extra prayers performed by Muslims at night in the Islamic month of Ramadan. Contrary to popular belief, they are not compulsory.[44] However, many Muslims pray these prayers in the evening during Ramadan. Some scholars maintain that Tarawih is neither fard or a Sunnah, but is the preponed Tahajjud (night prayer) prayer shifted to post-Isha' for the ease of believers. But a majority of Sunni scholars regard the Tarawih prayers as Sunnat al-Mu'akkadah, a salaat that was performed by the Islamic prophet Muhammad very consistently.

Recitation of the Quran

In addition to fasting, Muslims are encouraged to read the entire Quran. Some Muslims perform the recitation of the entire Quran by means of special prayers, called Tarawih. These voluntary prayers are held in the mosques every night of the month, during which a whole section of the Quran (juz', which is 1/30 of the Quran) is recited. Therefore, the entire Quran would be completed at the end of the month. Although it is not required to read the whole Quran in the Tarawih prayers, it is common.

Cultural practices

In some Muslim countries today, lights are strung up in public squares, and across city streets, to add to the festivities of the month. Lanterns have become symbolic decorations welcoming the month of Ramadan. In a growing number of countries, they are hung on city streets.[45][46][47] The tradition of lanterns as a decoration becoming associated with Ramadan is believed to have originated during the Fatimid Caliphate primarily centered in Egypt, where Caliph al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah was greeted by people holding lanterns to celebrate his ruling. From that time, lanterns were used to light mosques and houses throughout the capital city of Cairo. Shopping malls, places of business, and people's homes can be seen with stars and crescents and various lighting effects, as well.

As the nation with the world's largest Muslim population, Indonesia has diverse Ramadan traditions. On the island of Java, many Javanese Indonesians bathe in holy springs to prepare for fasting, a ritual known as Padusa. The city of Semarang marks the beginning of Ramadan with the Dugderan carnival, which involves parading the Warak ngendog, a horse-dragon hybrid creature allegedly inspired by the Buraq. In the Chinese-influenced capital city of Jakarta, fire crackers were traditionally used to wake people up for morning prayer, until the 19th century. Towards the end of Ramadan, most employees receive a one-month bonus known as Tunjangan Hari Raya. Certain kinds of food are especially popular during Ramadan, such as beef in Aceh, and snails in Central Java. The iftar meal is announced every evening by striking the bedug, a giant drum, in the mosque.

Common greetings during Ramadan are "Ramadan Mubarak" or "Ramadan Kareem", which wish the recipient a blessed or generous Ramadan.[48]

Penalties for infraction

In some Muslim countries, failing to fast or the open flouting of such behavior during Ramadan is considered a crime and is prosecuted as such. For instance, in Algeria, in October 2008 the court of Biskra condemned six people to four years in prison and heavy fines.[49]

In Kuwait, according to law number 44 of 1968, the penalty is a fine of no more than 100 Kuwaiti dinars, or jail for no more than one month, or both penalties, for those seen eating, drinking or smoking during Ramadan daytime.[50][51] In some places in the U.A.E., eating or drinking in public during the daytime of Ramadan is considered a minor offence and would be punished by up to 150 hours of community service.[52] In neighbouring Saudi Arabia, described by The Economist as taking Ramadan "more seriously than anywhere else",[53] there are harsher punishments, whereas in Malaysia, there are no such punishments.

In Egypt, alcohol sales are banned during Ramadan.[54]

In 2014 in Kermanshah, Iran, a non-Muslim was sentenced to having his lips burnt with a cigarette and five Muslims were publicly flogged with 70 stripes for eating during Ramadan.[55]

Other legal issues

Some countries have laws that amend work schedules during Ramadan. Under U.A.E. labor law, the maximum working hours are to be 6 hours per day and 36 hours per week. Qatar, Oman, Bahrain and Kuwait have similar laws.[56]

Health

Ramadan fasting is safe for healthy people, but those with medical conditions should seek medical advice.[57] The fasting period is usually associated with modest weight loss, but the weight tends to return afterwards.[58]

Renal disease

A review of the literature by an Iranian group suggested fasting during Ramadan might produce renal injury in patients with moderate (GFR <60 ml/min) or worse kidney disease, but was not injurious to renal transplant patients with good function or most stone forming patients.[59]

Crime rates

The correlation of Ramadan with crime rates is mixed: some statistics show that crime rates drop during Ramadan, while others show that it rises. Decreases in crime rates have been reported by the police in some cities in Turkey (Istanbul[60] and Konya[61]) and the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia.[62] A 2012 study showed that crime rates decreased in Iran during Ramadan, and that decrease was statistically significant.[63] A 2005 study found that there was a decrease in assault, robbery and alcohol-related crimes during Ramadan in Saudi Arabia, but only the decrease in alcohol-related crimes was statistically significant.[64] Increases in crime rates during Ramadan have been reported in Turkey,[65] Jakarta,[66][67][68] parts of Algeria,[69] Yemen[70] and Egypt.[71]

Various mechanisms have been proposed for the effect of Ramadan on crime:

- An Iranian cleric argues that fasting during Ramadan makes people less likely to commit crimes due to spiritual reasons.[72] Gamal al-Banna argues that fasting can stress people out, which can make them more likely to commit crimes. He criticized Muslims who commit crimes while fasting during Ramadan as "fake and superficial".[71]

- Police in Saudi Arabia attributed a drop in crime rates to the "spiritual mood prevalent in the country".[62]

- In Jakarta, Indonesia, police say that the traffic due to 7 million people leaving the city to celebrate Eid al-Fitr results in an increase in street crime. As a result, police deploy an additional 7,500 personnel.[68]

- During Ramadan, millions of pilgrims enter Saudi Arabia to visit Mecca. According to the Yemen Times, such pilgrims are usually charitable, and consequently smugglers traffic children in from Yemen to beg on the streets of Saudi Arabia.[70]

Ramadan in polar regions

The length of the dawn to sunset time varies in different parts of the world according to summer or winter solstices of the sun. Most Muslims fast for 11–16 hours during Ramadan. However, in polar regions, the period between dawn and sunset may exceed 22 hours in summers. For example, in 2014, Muslims in Reykjavik, Iceland, and Trondheim, Norway, fasted almost 22 hours, while Muslims in Sydney, Australia, fasted for only about 11 hours. Muslims in areas where continuous night or day is observed during Ramadan follow the fasting hours in the nearest city where fasting is observed at dawn and sunset. Alternatively, Muslims may follow Mecca time.[73][74][75]

Employment during Ramadan

Muslims will continue to work during Ramadan. The prophet Muhammad said that it is important to keep a balance between worship and work. In some Muslim countries, such as Oman, however, working hours are shortened during Ramadan.[76][77] It is often recommended that working Muslims inform their employers if they are fasting, given the potential for the observance to impact performance at work.[78] The extent to which Ramadan observers are protected by religious accommodation varies by country. Policies putting them at a disadvantage compared to other employees have been met with discrimination claims in the UK and the US.[79][80][81]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In Arabic phonology, it can be [rɑmɑˈdˤɑːn, ramadˤɑːn, ræmæˈdˤɑːn], depending on the region.

- ↑ The hadith of Jabir ibn Abdullah mentions that the Gospel was sent down on the 18th of Ramadan. Aliyev, Rafig Y. (June 2013). Loud Thoughts on Religion: A Version of the System Study of Religion. Useful Lessons for Everybody. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781490705217.

References

- 1 2 3 "The Umm al-Qura Calendar of Saudi Arabia". Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ BBC – Religions Retrieved 25 July 2012

- ↑ "Muslims worldwide start to observe Ramadan". The Global Times Online. 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "The Muslim World Observes Ramadan". Power Text Solutions. 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Schools – Religions". BBC. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, AbdAllah-Muhammad. "Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 124.". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Muslim-Ibn-Habaj, Abul-Hussain. "Sahih Muslim – Book 006 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 2378.". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Muslim-Ibn-Habaj, Abul-Hussain. "Sahih Muslim – Book 006 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 2391.". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Fasting (Al Siyam) – الصيام – Page 18, el Bahay el Kholi, 1998

- ↑ "Saudi Aramco World: Ramadan in the Farthest North". Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ IslamQA, "It is not permissible for one who is fasting to insult anyone", URL: http://islamqa.info/en/37658

- ↑ Islam, Andrew Egan – 2002 – page 24

- ↑ Dubai – Page 189, Andrea Schulte-Peevers – 2010

- ↑ Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, AbdAllah-Muhammad. "Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 125.". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Abu Dawud-Ibn-Ash'ath-AsSijisstani, Sulayman. "Sunan Abu-Dawud – (The Book of Prayer) – Detailed Injunctions about Ramadan, Hadith 1370". Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement of The University of Southern California. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, AbdAllah-Muhammad. "Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 199.". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Ad-Dausaree, Mahmood Bin Ahmad Bin Saaleh (2006). The Magnificence of Quran. Darussalam Publishers.

- 1 2 Aliyev, Rafig Y. (June 2013). Loud Thoughts on Religion: A Version of the System Study of Religion. Useful Lessons for Everybody. Trafford Publishing. p. 129. ISBN 9781490705217.

- ↑ al-Uthaymeen, Shaikh Saalih. Explanation of the Three Fundamental Principles of Islam (Salafi): Sharh Usool ath-Thalatha of Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahaab. Salafi Books.

- ↑ Quran Chapter 2, Revelation 183

- ↑ Aliyev, Rafig Y. (February 2013). Loud Thoughts on Religion: A Version of the System Study of Religion. Useful Lessons for Everybody. Trafford Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 9781490705217.

- ↑ See Ibn Qutaybah,op.cit.page 204; Cited by Sinasi Gunduz, The Knowledge of Life, Oxford University, 1994, p. 25, note 403: "Abu al-Fida, op-cit., p.148; Bar Habraeus, op.cit. p.266, Ibn Hazm claims that this fast is the fast of Ramadan (of the Muslims), but this is completely wrong."

- ↑ Jenkins, Philip (31 July 2006). The New Faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South (p. 182). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Muhammad Mustafa al-Azami, "The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments", 2nd Edition (2008), Azami Publishing House

- ↑ Hilal Sighting & Islamic Dates: Issues and Solution Insha'Allaah. Hilal Sighting Committee of North America (website). Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ↑ Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, AbdAllah-Muhammad. "Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 124". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Robinson, Neal (1999). Islam: A Concise Introduction. Washington: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-224-1.

- ↑ Ibn-Ismail-Bukhari, AbdAllah-Muhammad. "Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 125". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Ibn-Ismail-Bukhari, AbdAllah-Muhammad. "Sahih Bukhari – Book 032 (Praying at Night during Ramadhan), Hadith 238". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Muslim-Ibn-Habaj, Abul-Hussain. "Sahih Muslim – Book 006 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 2632". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Ruling on Voluntary Fasting After The Month Of Ramadan: Eid Day(s) And Ash-Shawaal". EsinIslam, Arab News & Information – By Adil Salahi. 11 September 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Book of Fasting – Sahih al-Bukhari – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Sahih Muslim Book 006, Hadith Number 2361.". Hadith Collection. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Muslims observe Ramadan, clerics explain significance". Guardian News, Nigeria. 4 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ Why Ramadan brings us together; BBC, 1 September 2008

- ↑ Help for the Heavy at Ramadan, Washington Post, 27 September 2008

- 1 2 El-Zibdeh, Dr. Nour. "Understanding Muslim Fasting Practices". todaysdietitian.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Quran 2:184

- ↑ Muslim-Ibn-Habaj, Abul-Hussain (2009). "Sahih Muslim – Book 006 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 2415". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Ibn-Ismail-Bukhari, AbdAllah-Muhammad (2009). "Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 144". hadithcollection.com. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ↑ Fletcher Stoeltje, Melissa (22 August 2009). "Muslims fast and feast as Ramadan begins". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Levy, Faye; Levy, Yakir (21 July 2012). "Ramadan's high note is often a dip". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Davis, James D. (8 August 2010). "Ramadan: Muslims feast and fast during holy month". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Tarawih Prayer a Nafl or Sunnah". Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Muslims begin fasting for Ramadan". ABC News. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Taryam Al Subaihi (29 July 2012). "The spirit of Ramadan is here, but why is it still so dark?". The National. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Cochran, Sylvia (8 August 2011). "How to decorate for Ramadan". Yahoo-Shine. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Ramadan 2015: Facts, History, Dates, Greeting And Rules About The Muslim Fast, Huffington Post, 15 June 2015

- ↑ "Algerians jailed for breaking Ramadan fast". Al Arabiya News. 7 October 2008.

- ↑ Press release by Kuwait Ministry Of Interior

- ↑ "KD 100 fine, one month prison for public eating, drinking". Friday Times. Kuwait Times Newspaper. 21 August 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ↑ Salama, Samir (16 July 2009). "New penalty for minor offences in UAE". Gulf News. Dubai, UAE: Al Nisr Publishing LLC. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ↑ "Ramadan in Saudi Arabia: Taking it to heart". The Economist. 11 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ↑ "Egypt's tourism minister 'confirms' alcohol prohibition on Islamic holidays beyond Ramadan," Al-Ahram, 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Christian sentenced by Iranian judge to have his lips burnt with a cigarette for eating during Ramadan". Mail Online. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ Employment Issues During Ramadan – The Gulf Region, DLA Piper Middle East.

- ↑ Azizi F (2010). "Islamic fasting and health". Ann. Nutr. Metab. 56 (4): 273–82. doi:10.1159/000295848. PMID 20424438.

- ↑ Sadeghirad B, Motaghipisheh S, Kolahdooz F, Zahedi MJ, Haghdoost AA (2014). "Islamic fasting and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Public Health Nutr. 17 (2): 396–406. doi:10.1017/S1368980012005046. PMID 23182306.

- ↑ Emami-Naini A, Roomizadeh P, Baradaran A, Abedini A, Abtahi M (August 2013). "Ramadan fasting and patients with renal diseases: A mini review of the literature". J Res Med Sci. Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 18 (8): 711–716. ISSN 1735-1995. PMC 3872613

. PMID 24379850.

. PMID 24379850. - ↑ "Crime rate falls during Ramadan". Today's Zaman. 21 August 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "Crime rate drops over Ramadan". Turkish Daily News. 16 November 2002. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Eastern Province crime falls 40% during Ramadan". 28 July 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ Tavakoli, Nasrin (2012), "Effect of spirituality on decreasing crimes and social damages: A case study on Ramadan" (PDF), International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences: 518–524

- ↑ "The effect of Ramadan on crime rates in Saudi Arabia, Hattab Ben Thawab Al-Sobaye" (PDF). Naif Arab University for Social Sciences, Thesis publication. 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "129 women killed in six months in Turkey, lawmaker says". Hurriyet Daily News. 11 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "Crime rates increase during Ramadhan". Jakarta Post. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "4 Gold Shop Robbers Killed, 2 Caught During Police Raids Across the City". Jakarta Post. 29 August 2009. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Anticipating Crime, 7,500 Policemen Put on Standby Along Ramadan". Department of Communication, Informatics and Public Relations of Jakarta Capital City. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ "Comment le Ramadhan bouleverse la vie des Algériens". El Watan, French. 24 August 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Yemen child trafficking to increase during Ramadan". Yemen Times. 20 August 2009. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011.

- 1 2 "Ramadan saw rise in violent domestic crimes". Daily News, Egypt. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011.

- ↑ "Ramadan and lower crime rates: The Ayatollah says that during Ramadan the number of criminal cases in the Judiciary diminish by a great degree.". 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ↑ See article "How Long Muslims Fast For Ramadan Around The World" -Huffingtonpost.co /31 July 2014 and article "Fasting Hours of Ramadan 2014" -Onislam.net / 29 June 2014 and article "The true spirit of Ramadan" -Gulfnews.com /31 July 2014

- ↑ See article by Imam Mohamad Jebara "The fasting of Ramadan is not meant to punish" http://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/jebara-the-fasting-of-ramadan-is-not-meant-to-punish

- ↑ Kassam, Ashifa (2016-07-03). "Arctic Ramadan: fasting in land of midnight sun comes with a challenge". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ↑ "Ramadan working hours announced in Oman". Times of Oman. 22 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ramadan working hours announced for public and private sectors". Times of Oman. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Working Muslim in Ramadan" (PDF). Working Muslim. 2011. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ↑ Lewis Silkin (26 April 2016). "Lewis Silkin – Ramadan – employment issues". lewissilkinemployment.com. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ "Reasonable Accommodations for Ramadan? Lessons From 2 EEOC Cases". Free Enterprise. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ↑ "EEOC And Electrolux Reach Settlement In Religious Accommodation Charge Brought By Muslim Employees". eeoc.gov. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ramadan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Travelling during Ramadan. |

- Ramadan Calendar for 2016 (1437 Hijri)

- Complete Guide to Ramadhan including Rules, Duas, Itikaaf, Laylatul Qadr, Sadaqatul Fitr etc

- 15 Hadiths on Ramadan

- Articles on Ramadan

- Ramadan Articles & Resources

- Purpose of Fasting in Islam: "And Fast Until The Onset Of Night"

- Ramadan Customs, Observance and Practices