Plantar fasciitis

| Plantar fasciitis | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | plantar fasciosis, plantar fasciopathy, jogger's heel |

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, sports medicine, plastic surgery, podiatry |

| ICD-10 | M72.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 728.71 |

| DiseasesDB | 10114 |

| MedlinePlus | 007021 |

| eMedicine | pmr/107 orthoped/142 |

| Patient UK | Plantar fasciitis |

| MeSH | D036981 |

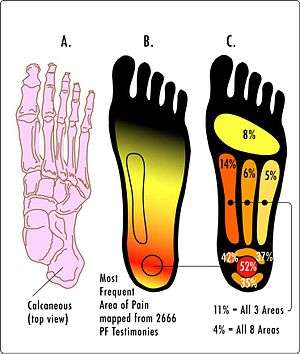

Plantar fasciitis is a disorder that results in pain in the heel and bottom of the foot.[1] The pain is usually most severe with the first steps of the day or following a period of rest.[2] Pain is also frequently brought on by bending the foot and toes up towards the shin and may be worsened by a tight Achilles tendon.[2][3] The condition typically comes on slowly.[3] In about a third of people both legs are affected.[1] Typically there are no fevers or night sweats.[3]

The causes of plantar fasciitis are not entirely clear. Risk factors include overuse such as from long periods of standing, an increase in exercise, and obesity.[1] It is also associated with inward rolling of the foot and a lifestyle that involves little exercise.[1][2] While heel spurs are frequently found it is unclear if they have a role in causing the condition. Plantar fasciitis is a disorder of the insertion site of the ligament on the bone characterized by micro tears, breakdown of collagen, and scarring.[1] As inflammation plays a lesser role, many feel the condition should be renamed plantar fasciosis.[1][4] The diagnosis is typically based on signs and symptoms with ultrasound sometimes used to help.[1] Other conditions with similar symptoms include osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, heel pad syndrome, and reactive arthritis.[5][6]

Most cases of plantar fasciitis resolve with time and conservative methods of treatment.[2][7] Usually for the first few weeks people are advised to rest, change their activities, take pain medications, and stretch. If this is not sufficient physiotherapy, orthotics, splinting, or steroid injections may be options. If other measures do not work extracorporeal shockwave therapy or surgery may be tried.[2]

Between 4% and 7% of people have heel pain at any given time and about 80% of these cases are due to plantar fasciitis.[1][5] Approximately 10% of people have the disorder at some point during their life.[8] It becomes more common with age. It is unclear if one sex is more affected than the other.[1]

Signs and symptoms

When plantar fasciitis occurs, the pain is typically sharp[9] and usually unilateral (70% of cases).[7] Heel pain is worsened by bearing weight on the heel after long periods of rest.[10] Individuals with plantar fasciitis often report their symptoms are most intense during their first steps after getting out of bed or after prolonged periods of sitting.[2] Improvement of symptoms is usually seen with continued walking.[2][6][9] Rare, but reported symptoms include numbness, tingling, swelling, or radiating pain.[11]

If the plantar fascia continues to be overused in the setting of plantar fasciitis, the plantar fascia can rupture. Typical signs and symptoms of plantar fascia rupture include a clicking or snapping sound, significant local swelling, and acute pain in the sole of the foot.[9]

Risk factors

Identified risk factors for plantar fasciitis include excessive running, standing on hard surfaces for prolonged periods of time, high arches of the feet, the presence of a leg length inequality, and flat feet. The tendency of flat feet to excessively roll inward during walking or running makes them more susceptible to plantar fasciitis.[2][10][12] Obesity is seen in 70% of individuals who present with plantar fasciitis and is an independent risk factor.[3] Studies have suggested a strong association exists between an increased body mass index and the development of plantar fasciitis in the non-athletic population; this association between weight and plantar fasciitis has not been observed in the athletic population.[7] Achilles tendon tightness and inappropriate footwear have also been identified as significant risk factors.[13]

Pathophysiology

The cause of plantar fasciitis is poorly understood and is thought to likely have several contributing factors.[13] The plantar fascia is a thick fibrous band of connective tissue that originates from the medial tubercle and anterior aspect of the heel bone. From there, the fascia extends along the sole of the foot before inserting at the base of the toes, and supports the arch of the foot.[3][10][12]

Originally, plantar fasciitis was believed to be an inflammatory condition of the plantar fascia. However, within the last decade, studies have observed microscopic anatomical changes indicating that plantar fasciitis is actually due to a noninflammatory structural breakdown of the plantar fascia rather than an inflammatory process.[7][13]

Due to this shift in thought about the underlying mechanisms in plantar fasciitis, many in the academic community have stated the condition should be renamed plantar fasciosis.[6] The structural breakdown of the plantar fascia is believed to be the result of repetitive microtrauma (small tears).[11][12] Microscopic examination of the plantar fascia often shows myxomatous degeneration, connective tissue calcium deposits, and disorganized collagen fibers.[4]

Disruptions in the plantar fascia's normal mechanical movement during standing and walking (known as the Windlass mechanism) are thought to contribute to the development of plantar fasciitis by placing excess strain on the calcaneal tuberosity.[13] Other studies have also suggested that plantar fasciitis is not actually due to inflamed plantar fascia, but may be a tendon injury involving the flexor digitorum brevis muscle located immediately deep to the plantar fascia.[12]

Diagnosis

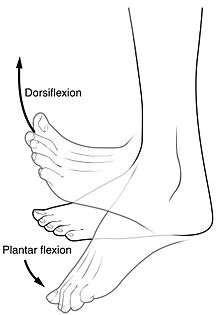

Plantar fasciitis is usually diagnosed by a health care provider after consideration of a person's presenting history, risk factors, and clinical examination.[2][14][15] Tenderness to palpation along the inner aspect of the heel bone on the sole of the foot may be elicited during the physical examination.[2][10] The foot may have limited dorsiflexion due to tightness of the calf muscles or the Achilles tendon.[7] Dorsiflexion of the foot may elicit the pain due to stretching of the plantar fascia with this motion.[2][11] Diagnostic imaging studies are not usually needed to diagnose plantar fasciitis.[7] However, in certain cases a physician may decide imaging studies (such as X-rays, diagnostic ultrasound or MRI) are warranted to rule out serious causes of foot pain.

Other diagnoses that are typically considered include fractures, tumors, or systemic disease if plantar fasciitis pain fails to respond appropriately to conservative medical treatments.[2][10] Bilateral heel pain or heel pain in the context of a systemic illness may indicate a need for a more in-depth diagnostic investigation. Diagnostic tests such as a CBC or serological markers of inflammation, infection, or autoimmune disease such as C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, HLA-B27, uric acid, or Lyme disease antibodies may also be obtained.[5] Neurological deficits may prompt an investigation with electromyography to evaluate for damage to the nerves or muscles.[11]

An incidental finding associated with this condition is a heel spur, a small bony calcification on the calcaneus (heel bone), which can be found in up to 50% of those with plantar fasciitis.[6] In such cases, it is the underlying plantar fasciitis that produces the heel pain, and not the spur itself.[12] The condition is responsible for the creation of the spur though the clinical significance of heel spurs in plantar fasciitis remains unclear.[11]

Imaging

Medical imaging is not routinely needed as it is expensive and does not typically change how plantar fasciitis is managed.[13] When the diagnosis is not clinically apparent, lateral view x-rays of the ankle are the recommended imaging modality to assess for other causes of heel pain such as stress fractures or bone spur development.[7]

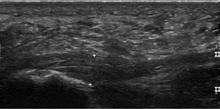

Normally the plantar fascia has three fascicles with the central fascicle thickest at 4 mm, the lateral fascicle at 2 mm and the medial at less than a millimeter in thickness.[16] In theory, the likeliness of fasciitis increases with increasing thickness of plantar fascia at the calcaneal insertion, with thickness of more than 4.5 mm being somewhat useful on ultrasound and 4 mm on MRI.[17] Findings on imaging such as plantar aponeurosis thickening, however, may be absent in symptomatic individuals or present in asymptomatic individuals thereby limiting the utility of such observations.[12]

3-phase bone scan is a sensitive modality to detect active plantar fasciitis. Furthermore, 3-phase bone scan can be used to monitor response to therapy, as demonstrated by decreased uptake after corticosteroid injections.[18]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for heel pain is extensive and includes pathological entities including, but not limited to the following: calcaneal stress fracture, calcaneal bursitis, osteoarthritis, spinal stenosis involving the nerve roots of lumbar spinal nerve 5 (L5) or sacral spinal nerve 1 (S1), calcaneal fat pad syndrome, hypothyroidism, seronegative spondyloparthopathies such as reactive arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or rheumatoid arthritis (more likely if pain is present in both heels),[5] plantar fascia rupture, and compression neuropathies such as tarsal tunnel syndrome or impingement of the medial calcaneal nerve.[3][5][7]

A determination about a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis can usually be made based on a person's medical history and physical examination.[19] In cases in which the physician suspects fracture, infection, or some other serious underlying condition, an x-ray may be used to make a differential diagnosis.[19] However, and especially for people who stand or walk a lot at work, x-rays should not be used to screen for plantar fasciitis unless imaging is otherwise indicated as using it outside of medical guidelines is unnecessary health care.[19]

Treatment

Non-surgical

About 90% of plantar fasciitis cases will improve within six months with conservative treatment,[8] and within a year regardless of treatment.[2][7] Many treatments have been proposed for plantar fasciitis. Most have not been adequately investigated and there is little evidence to support recommendations for such treatments.[2] First-line conservative approaches include rest, heat, ice, and calf-strengthening exercises; techniques to stretch the calf muscles, Achilles tendon, and plantar fascia; weight reduction in the overweight or obese; and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin or ibuprofen.[6][10][20] NSAIDs are commonly used to treat plantar fasciitis, but fail to resolve the pain in 20% of people.[10]

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) is an effective treatment modality for plantar fasciitis pain unresponsive to conservative nonsurgical measures for at least three months. Evidence from meta-analyses suggests significant pain relief lasts up to one year after the procedure.[8][21] However, debate about the therapy's efficacy has persisted.[4] ESWT can be performed with or without anesthesia though studies have suggested that the therapy is less effective when anesthesia is given.[22] Complications from ESWT are rare and typically mild when present.[22] Known complications of ESWT include the development of a mild hematoma or an ecchymosis, redness around the site of the procedure, or migraine.[22]

Corticosteroid injections are sometimes used for cases of plantar fasciitis refractory to more conservative measures. The injections may be an effective modality for short-term pain relief up to one month, but studies failed to show effective pain relief after three months.[4] Notable risks of corticosteroid injections for plantar fasciitis include plantar fascia rupture,[3] skin infection, nerve or muscle injury, or atrophy of the plantar fat pad.[2][10] Custom orthotic devices have been demonstrated as an effective method to reduce plantar fasciitis pain for up to 12 weeks.[23] The long-term effectiveness of custom orthotics for plantar fasciitis pain reduction requires additional study.[24] Orthotic devices and certain taping techniques are proposed to reduce pronation of the foot and therefore reduce load on the plantar fascia resulting in pain improvement.[12]

Another treatment technique known as plantar iontophoresis involves applying anti-inflammatory substances such as dexamethasone or acetic acid topically to the foot and transmitting these substances through the skin with an electric current.[10] Moderate evidence exists to support the use of night splints for 1–3 months to relieve plantar fasciitis pain that has persisted for six months.[7] The night splints are designed to position and maintain the ankle in a neutral position thereby passively stretching the calf and plantar fascia overnight during sleep.[7] Other treatment approaches may include supportive footwear, arch taping, and physical therapy.[6]

Surgery

Plantar fasciotomy is often considered after conservative treatment has failed to resolve the issue after six months and is viewed as a last resort.[2][6] Minimally invasive and endoscopic approaches to plantar fasciotomy exist but require a specialist who is familiar with certain equipment. The availability of these surgical techniques is currently limited.[5] A 2012 study found 76% of patients who underwent endoscopic plantar fasciotomy had complete relief of their symptoms and had few complications (level IV evidence).[4] Heel spur removal during plantar fasciotomy has not been found to improve the surgical outcome.[25] Plantar heel pain may occur for multiple reasons and release of the lateral plantar nerve branch may be performed alongside the plantar fasciotomy in select cases.[5][25] Possible complications of plantar fasciotomy include nerve injury, instability of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot,[26] fracture of the calcaneus, prolonged recovery time, infection, rupture of the plantar fascia, and failure to improve the pain.[2] Coblation surgery has recently been proposed as alternative surgical approaches for the treatment of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis.[25]

Unproven treatments

Botulinum Toxin A injections as well as similar techniques such as platelet-rich plasma injections and prolotherapy remain controversial.[4][7][10][27]

Dry needling is also being researched for treatment of plantar fasciitis.[28] A systematic review of available research found limited evidence of effectiveness for this technique.[29] The studies were reported to be inadequate in quality and too diverse in methodology to enable reaching a firm conclusion.[29]

Epidemiology

Plantar fasciitis is the most common type of plantar fascia injury[9] and is the most common reason for heel pain, responsible for 80% of cases. The condition tends to occur more often in women, military recruits, older athletes, the obese, and young male athletes.[7][11][12]

Plantar fasciitis is estimated to affect 1 in 10 people at some point during their lifetime and most commonly affects people between 40–60 years of age.[3][4] In the United States alone, more than two million people receive treatment for plantar fasciitis.[3] The cost of treating plantar fasciitis in the United States is estimated to be $284 million each year.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Beeson P (September 2014). "Plantar fasciopathy: revisiting the risk factors". Foot and Ankle Surgery. 20 (3): 160–5. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2014.03.003. PMID 25103701.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Goff JD, Crawford R (September 2011). "Diagnosis and treatment of plantar fasciitis". Am Fam Physician. 84 (6): 676–82. PMID 21916393.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rosenbaum AJ, DiPreta JA, Misener D (March 2014). "Plantar Heel Pain". Med Clin North Am. 98 (2): 339–52. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2013.10.009. PMID 24559879.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lareau CR, Sawyer GA, Wang JH, DiGiovanni CW (June 2014). "Plantar and Medial Heel Pain: Diagnosis and Management". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 22 (6): 372–80. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-22-06-372. PMID 24860133.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cutts S, Obi N, Pasapula C, Chan W (November 2012). "Plantar fasciitis". Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 94 (8): 539–42. doi:10.1308/003588412X13171221592456. PMC 3954277

. PMID 23131221.

. PMID 23131221. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tu P, Bytomski JR (October 2011). "Diagnosis of heel pain". Am Fam Physician. 84 (8): 909–16. PMID 22010770.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Tahririan MA, Motififard M, Tahmasebi MN, Siavashi B (August 2012). "Plantar fasciitis". J Res Med Sci. 17 (8): 799–804. PMC 3687890

. PMID 23798950.

. PMID 23798950. - 1 2 3 Zhiyun L, Tao J, Zengwu S (July 2013). "Meta-analysis of high-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy in recalcitrant plantar fasciitis". Swiss Med Wkly. 143: w13825. doi:10.4414/smw.2013.13825. PMID 23832373.

- 1 2 3 4 Jeswani T, Morlese J, McNally EG (September 2009). "Getting to the heel of the problem: plantar fascia lesions". Clin Radiol. 64 (9): 931–9. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2009.02.020. PMID 19664484.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Molloy LA (November 2012). "Managing chronic plantar fasciitis: when conservative strategies fail". JAAPA. 25 (11): 48, 50, 52–53. doi:10.1097/01720610-201211000-00009. PMID 23620924.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Monto RR (December 2013). "Platelet-rich plasma and plantar fasciitis". Sports Med Arthrosc. 21 (4): 220–4. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e318297fa8d. PMID 24212370.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Orchard J (October 2012). "Plantar fasciitis". BMJ. 10 (345): e6603. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6603. PMID 23054045.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yin MC, Ye J, Yao M, Cui XJ, Xia Y, Shen QX, Tong ZY, Wu XQ, Ma JM, Mo W (March 2014). "Is Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Clinical Efficacy for Relief of Chronic, Recalcitrant Plantar Fasciitis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo or Active-Treatment Controlled Trials". Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 95: 1585–1593. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.01.033. PMID 24662810.

- ↑ Buchbinder R (May 2004). "Plantar Fasciitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (21): 2159–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp032745. PMID 15152061.

- ↑ Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J (December 2005). "Plantar fasciitis: Evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy". American Family Physician. 72 (11): 2237–42. PMID 16342847.

- ↑ Ehrmann, C; Maier, M; Mengiardi, B; Pfirrmann, CW; Sutter, R (September 2014). "Calcaneal attachment of the plantar fascia: MR findings in asymptomatic volunteers.". Radiology. 272 (3): 807–14. doi:10.1148/radiol.14131410. PMID 24814176.

- ↑ League, AC (March 2008). "Current concepts review: plantar fasciitis.". Foot & ankle international. 29 (3): 358–66. doi:10.3113/fai.2008.0358. PMID 18348838.

- ↑ Pelletier-Galarneau M, Martineau P, Gaudreault M, Pham X (2015). "Review of running injuries of the foot and ankle: clinical presentation and SPECT-CT imaging patterns". Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 5 (4): 305–16. PMC 4529586

. PMID 26269770.

. PMID 26269770. - 1 2 3 American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (February 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, retrieved 24 February 2014, which cites

- Haas, N; Beecher, P; Easly, M; et al. (2011). "Ankle and foot disorders". In Kurt T. Hegmann. Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. p. 1182. ISBN 978-0615452272.

- ↑ "Plantar Fasciitis and Bone Spurs". American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ↑ Aqil A, Siddiqui MR, Solan M, Redfern DJ, Gulati V, Cobb JP (November 2013). "Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is effective in treating chronic plantar fasciitis: a meta-analysis of RCTs". Clin Orthop Relat Resl. 471 (11): 3645–52. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3132-2. PMID 23813184.

- 1 2 3 Wang CJ (March 2012). "Extracorporeal shockwave therapy in musculoskeletal disorders". J Orthop Surg Res. 7 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-7-11. PMC 3342893

. PMID 22433113.

. PMID 22433113. - ↑ Lee SY, McKeon P, Hertel J (February 2009). "Does the use of orthoses improve self-reported pain and function measures in patients with plantar fasciitis? A meta-analysis". Phys There Sport. 10 (1): 12–8. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2008.09.002. PMID 19218074.

- ↑ Anderson J, Stanek J (May 2013). "Effect of foot orthoses as treatment for plantar fasciitis or heel pain". J Sport Rehabil. 22 (2): 130–6. PMID 23037146.

- 1 2 3 Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, Mendicino RW, Schuberth JM, Vanore JV, Weil LS, Zlotoff HJ, Bouché R, Baker J (May–June 2010). "The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010". J Foot Ankle Surg. 49 (3 Suppl): S1–19. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2010.01.001. PMID 20439021.

- ↑ Tweed JL, Barnes MR, Allen MJ, Campbell JA (September–October 2009). "Biomechanical consequences of total plantar fasciotomy: a review of the literature". J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 99 (5): 422–30. PMID 19767549.

- ↑ Monto R (April 2014). "Platelet-rich plasma efficacy versus corticosteroid injection treatment for chronic severe plantar fasciitis". Foot and Ankle International. 35 (4): 313–318. doi:10.1177/1071100713519778. PMID 24419823.

- ↑ Cotchett MP, Landorf KB, Munteanu SE, Raspovic A (January 2011). "Effectiveness of trigger point dry needling for plantar heel pain: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial". Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 4 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1757-1146-4-5. PMC 3035595

. PMID 21255460.

. PMID 21255460. - 1 2 Cotchett MP, Landorf KB, Munteanu SE (September 2010). "Effectiveness of dry needling and injections of myofascial trigger points associated with plantar heel pain: a systematic review". Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 3 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1757-1146-3-18. PMC 2942821

. PMID 20807448.

. PMID 20807448.