Piloting (navigation)

Piloting (on water)[1] or pilotage (in the air[2] also British English[3]) or land navigation[4] is navigating, using fixed points of reference on the sea or on land, usually with reference to a nautical chart, aeronautical chart or topographic map, to obtain a fix of the position of the vessel, aircraft or land traveler with respect to a desired course or location. Horizontal fixes of position from known reference points may be obtained by sight or by radar. Vertical fixes of position may be obtained by depth sounder or by altimeter. Piloting is usually practiced close to shore or on inland waterways. Pilotage is practiced under visual meteorological conditions for flight. Divers use related techniques for underwater navigation.[5]

Piloting references

Charts

Depending on whether one is navigating on a water course, in the air or on land, a different chart applies for the navigator:

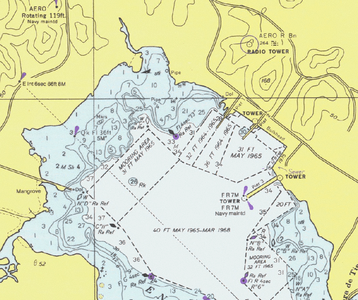

- Nautical charts – show coastal regions and depict depths of water and land features, natural features of the seabed, details of the coastline, navigational hazards, locations of natural and human-made aids to navigation, and human-made structures such as harbours, buildings and bridges.

- Aeronautical charts – for visual meteorological conditions depict terrain, geographic features, navigational aids and other aids to navigation. They vary in scale from 1:1,000,000 for world aeronautical charts to 1:250,000.

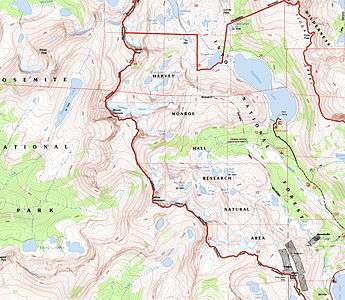

- Topographic maps – show landforms and terrain, lakes and rivers, forest cover, administrative areas, populated areas, roads and railways, and other man-made features.[6]

- Cartography showing man-made and natural features that can be used as points of reference appropriate to the type of navigation.

-

Nautical chart – includes water depth.

-

Aeronautical chart – includes elevation.

-

Topographic map – emphasizes contours – suitable for land navigation.

Maritime piloting

Coastal mariners often use reference manuals, called "pilots" for navigating coastal waters. In addition to providing descriptions of shipping channels and coastal profiles, they discuss weather, currents and other topics of interest to mariners. Notable guides include a world-wide series of "Sailing Directions" by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (formerly by the British Admiralty) that includes, most notably, the English Channel, the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf.[7] Another series world-wide series of Sailing Directions is by the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency,[8] which has planning guide and enroute portions. The "United States Coast Pilot", by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Coast Survey, covers the coastal and intracoastal waters and the Great Lakes of the United States.[9]

Points of reference

Common types of visual reference point used for piloting and pilotage include:[10]

Day

- Natural features: Mountains, hills, lakes, rivers and coastal features such as cliffs, rocks and beaches

- Navigational aids: sea marks (including buoys and beacons) and landmarks

- Other structures: Airports, cities, dams, highways, and radio antennas

Night

- Lighted navigational aids: Lighthouses, lightvessels and lighted sea marks

- Lighted structures: Airports, illuminated towers and buildings

Vertical

Depth, measured with a depth sounder or lead line, can be used to identify a bathymetric contour or crossing point. Similarly, elevation can be used to confirm a geographic contour or crossing point. Measurement of depth and altitude allow vessels and aircraft navigators to confirm clear passage over obstructions.[3]

Fix of position

Instruments used

On shipboard, navigators may use a pelorus to obtain bearings, relative to the vessel, from charted objects. A hand bearing compass provides magnetic bearings.[10] On land a hand compass provides bearings to landmarks.[11]

Afloat

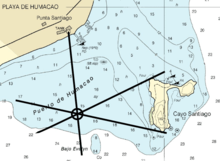

Mariners use position-fixing navigation, to obtain a "position fix" or "fix" by measuring the bearing of the navigator's current position from known points of reference. A visual fix of position can be made by using any sighting device with a bearing indicator to obtain position lines from the navigator's current position to each point of reference. Two or more objects of known position are sighted as points of reference, and the bearings recorded. Bearing lines or transits are then plotted on a chart through the locations of the sighted items. The intersection of these lines is then the current position of the navigator.[3]

Usually, a fix is where two or more position lines intersect at any given time. If three position lines can be obtained, the resulting "cocked hat", where the 3 lines do not intersect at the same point, but create a triangle where the vessel is inside, gives the navigator an indication of the accuracy in the three separate position lines.[3]

If two geographic features are visually aligned (the edge of an island aligned with the edge of an island behind, a flag pole and a building, etc.), the extension of the line joining the features is called a "transit". A transit is not affected by compass accuracy, and is often used to check a compass for errors.[12]

The most accurate fixes occur when the position lines are at right angles to each other.[3]

Aloft

Flying at low altitudes and with sufficient visibility, aircraft pilots use nearby rivers, roads, railroad tracks and other visual references to establish their position.[2]

Course versus ground track

The line connecting fixes is the track over the ground or sea bottom. The navigator compares the ground track with the navigational course for that leg of the intended route, in order to make a correction in "heading", the direction in which the craft is pointed to maintain its course in compensation for cross-currents of wind or water that may carry the craft off course.[3]

Piloting in channels and rivers

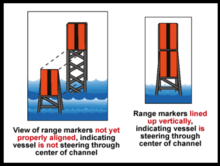

Where a channel is narrow, as in some harbor entrances and on some rivers, a system of beacons allows mariners to align pairs of daymarks, called "range markers", to form a "leading line" (British English)[3] or "range axis" (American English),[13] along which to navigate safely. When lighted, these markers are called "leading lights" (British English) or "range lights" (American English). The relative positions of the marks and the vessel affect the accuracy of perceiving the leading line.

See also

- Land navigation (military)

- Maritime pilot

- Pilot (aeronautics)

- Underwater navigation by divers

- Bowditch's American Practical Navigator

References

- ↑ Maloney, Elbert S. (December 2003). "Chapter 16: Basic piloting procedures". Chapman Piloting and Seamanship (64th ed.). New York, NY: Hearst Communications Inc. ISBN 1-58816-089-0.

- 1 2 NASA. "Aviation Navigation – Basic Navigation". Virtual Skies. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2016-05-13.

Pilotage: A method of navigation in which the pilot, flying at low altitudes, uses visual references and compares symbols on aeronautical charts with surface features on the ground in order to navigate.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bartlett, Tim (February 25, 2008), Adlard Coles Book of Navigation, Adlard Coles, p. 176, ISBN 978-0713689396

- ↑ United States Army (2007). Army Training Circular TC 3-25.26: U.S. Army Map Reading and Land Navigation Handbook. ISBN 9781420928235.

- ↑ UK Divers (October 16, 2007). "Underwater Navigation". UKDivers.net. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

Pilotage – Navigation by reference to terrain features, both natural and artificial, usually with the aid of an appropriate chart.

- ↑ Government of Canada (2016-04-08). "National Topographic System Maps". Earth Sciences – Geography. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- ↑ Hydrographic Office (2015). "Admiralty Nautical Products and Services – Paper publications". United Kingdom. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

Often referred to as Pilots, Sailing Directions are designed for use by the merchant mariner on all classes of ocean-going vessels with essential information on all aspects of navigation. Sailing Directions are complementary to ADMIRALTY Standard Nautical Charts and provide worldwide coverage in 75 volumes.

- ↑ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. "Sailing Directions Enroute". Maritime Safety Information. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

Sailing Directions (Enroute) include detailed coastal and port approach information, supplementing the largest scale chart of the area. Each publication is subdivided into geographic regions, called sectors, which contain information about the coastal weather, currents, ice, dangers, features and ports, as well as a graphic key to the charts available for the area.

- ↑ Office of Coast Survey. "United States Coast Pilot®". Nautical Charts & Pubs. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

The United States Coast Pilot® consists of a series of nautical books that cover a variety of information important to navigators of coastal and intracoastal waters and the Great Lakes. Issued in nine volumes, they contain supplemental information that is difficult to portray on a nautical chart.

- 1 2 Bowditch, Nathaniel; National Imagery and Mapping Agency (2002), "Chapter 8: Piloting", The American practical navigator : an epitome of navigation, Paradise Cay Publications, p. 896, ISBN 9780939837540

- ↑ Frazer, Persifor, A Convenient Device to be Applied to the Hand Compass, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 22, No. 118 (Mar., 1885), p. 216

- ↑ Manley, Pat (2008), Practical Navigation for the Modern Boat Owner (PDF), Wiley Nautical, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, p. 68, ISBN 978-0470516133, retrieved 2016-05-08

- ↑ United States Coast Guard Auxiliary (December 19, 2013), National Short Range Aids to Navigation – Training Guide (PDF), Washington: United States Coast Guard, p. 28, retrieved 2016-05-08

Outside links

American Practical Navigator – Chapter 8: Piloting