Bradyrhizobium

| Bradyrhizobium | |

|---|---|

| |

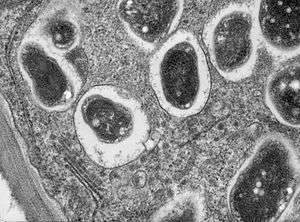

| Cross section though a soybean (Glycine max 'Essex') root nodule.Bradyrhizobium japonicum infects the roots and establishes a nitrogen fixing symbiosis. This high magnification image shows part of a cell with single bacteroids within their symbiosomes | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Alphaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Rhizobiales |

| Family: | Bradyrhizobiaceae |

| Genus: | Bradyrhizobium Jordan 1982 |

| Type species | |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Bradyrhizobium is a genus of Gram-negative soil bacteria, many of which fix nitrogen. Nitrogen fixation is an important part of the nitrogen cycle. Plants cannot use atmospheric nitrogen (N2); they must use nitrogen compounds such as nitrates.

Characteristics

Bradyrhizobium species are Gram-negative bacilli (rod-shaped) with a single subpolar or polar flagellum. They are common soil-dwelling micro-organisms that can form symbiotic relationships with leguminous plant species where they fix nitrogen in exchange for carbohydrates from the plant. Like other rhizobia, many members of this genus have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into forms readily available for other organisms to use. Bradyrhizobia are also major components of forest soil microbial communities, where strains isolated from these soils are not typically capable of nitrogen fixation or nodulation.[4] They are slow-growing in contrast to Rhizobium species, which are considered fast-growing rhizobia. In a liquid medium, Bradyrhizobium species take 3–5 days to create a moderate turbidity and 6–8 hours to double in population size. They tend to grow best with pentoses as carbon sources.[5] Some strains (for example, USDA 6 and CPP) are capable of oxidizing carbon monoxide aerobically.[6]

Nodulation

Nodule formation

Nodules are growths on the roots of leguminous plants where the bacteria reside. The plant roots secrete amino acids and sugars into the rhizosphere. The rhizobia move toward the roots and attach to the root hairs. The plant then releases flavanoids, which induce the expression of nod genes within the bacteria. The expression of these genes results in the production of enzymes called nod factors that initiate root hair curling. During this process, the rhizobia are curled up with the root hair. The rhizobia penetrate the root hair cells with an infection thread that grows through the root hair into the main root. This causes the infected cells to divide and form a nodule. The rhizobia can now begin nitrogen fixation.

Nod genes

Over 55 genes are known to be associated with nodulation.[7] NodD is essential for the expression of the other nod genes.[8] The two different nodD genes are: nodD1 and nodD2. Only nodD1 is needed for successful nodulation.[7]

Nitrogen fixation

Bradyrhizobium and other rhizobia take atmospheric nitrogen and fix it into ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+). Plants cannot use atmospheric nitrogen; they must use a combined or fixed form of the element. After photosynthesis, nitrogen fixation (or uptake) is the most important process for the growth and development of plants.[9] The levels of ureide nitrogen in a plant correlate with the amount of fixed nitrogen the plant takes up.[10]

Genes

Nif and fix are important genes involved in nitrogen fixation among Bradyrizobium species. Nif genes are very similar to genes found in Klebsiella pneumoniae, a free-living diazotroph. The genes found in bradyrhizobia have similar function and structure to the genes found in K. pneumoniae. Fix genes are important for symbiotic nitrogen fixation and were first discovered in rhizobia species. The nif and fix genes are found in at least two different clusters on the chromosome. Cluster I contains most of the nitrogen fixation genes. Cluster II contains three fix genes located near nod genes.[11]

Diversity

This genus of bacteria can form either specific or general symbioses;[5] one species of Bradyrhizobium may only be able to nodulate one legume species, whereas other Bradyrhizobium species may be able to nodulate several legume species. Ribosomal RNA is highly conserved in this group of microbes, making Bradyrhizobium extremely difficult to use as an indicator of species diversity. DNA-DNA hybridizations have been used instead and show more diversity. However, few phenotypic differences are seen, so not many species have been named.[12]

Significance

Grain legumes are cultivated on about 1.5 million km2 of land per year.[9] The amount of nitrogen fixed annually is about 44–66 million tons worldwide, providing almost half of all nitrogen used in agriculture.[13]

Bradyrhizobium has also been identified as a contaminant of DNA extraction kit reagents and ultra-pure water systems, which may lead to its erroneous appearance in microbiota or metagenomic datasets.[14] The presence of nitrogen fixing bacteria as contaminants may be due to the use of nitrogen gas in ultra-pure water production to inhibit microbial growth in storage tanks.[15]

Application

Bradyrhizobia fix more nitrogen than the plant can use. The excess nitrogen is left in the soil and available for other plants or later crops. Intercropping with a legume has the potential to decrease the need for applied fertilizer. Commercial inoculants of Bradyrhizobium are available. These can be applied as a peat or liquid directly to the seed before planting.

Species

- Bradyrhizobium betae was isolated from tumor-like root deformations on sugar beets; they have an unknown symbiotic status.[12]

- Bradyrhizobium elkanii, Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens, and Bradyrhizobium liaoningense establish symbiosis with soybeans.[12]

- Bradyrhizobium japonicum nodulates soybeans, cowpeas, mung beans, and siratro.[12]

- Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense nodulates Lespedeza.[12]

- Bradyrhizobium canariense nodulates genistoid legumes endemic to the Canary Islands. It has also been found in lupin and serradella nodules in western Australia and southern Africa.[12]

References

- ↑ "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature —Bradyrhizobium". Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- 1 2 Kalita, M; Małek, W (2010). "Genista tinctoria microsymbionts from Poland are new members of Bradyrhizobium japonicum bv. Genistearum". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 33 (5): 252–9. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2010.03.005. PMID 20452160.

- ↑ Ramirez-Bahena, M. -H.; Chahboune, R.; Peix, A.; Velazquez, E. (2012). "Reclassification of Agromonas oligotrophica into the genus Bradyrhizobium as Bradyrhizobium oligotrophicum comb. Nov". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 63: 1013–6. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.041897-0. PMID 22685107.

- ↑ VanInsberghe, David; Maas, Kendra; Cardenas, Erick; Strachan, Cameron; Hallam, Steven; Mohn, William (2015). "Non-symbiotic Bradyrhizobium ecotypes dominate North American forest soils". The ISME journal. 9: 2435–2441. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.54.

- 1 2 P. Somasegaran (1994). Handbook for rhizobia: methods in legume-rhizobium technology. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–6, 167. ISBN 0-387-94134-7.

- ↑ Gary, King (2003). "Molecular and culture-based analyses of aerobic carbon monoxide oxidizer diversity". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (12): 7257–7265. doi:10.1128/aem.69.12.7257-7265.2003. PMC 309980

. PMID 14660374.

. PMID 14660374. - 1 2 Stacey, Gary (1995). "Bradyrhizobium japonicumnodulation genetics". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 127 (1–2): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07441.x. PMID 7737469.

- ↑ Stacey, G; Sanjuan, J.; Luka, S.; Dockendorff, T.; Carlson, R.W. (1995). "Signal exchange in the Bradyrhizobium-soybean symbiosis". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 27 (4–5): 473–483. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(95)98622-U.

- 1 2 Caetanoanolles, G (1997). "Molecular dissection and improvement of the nodule symbiosis in legumes". Field Crops Research. 53: 47–68. doi:10.1016/S0378-4290(97)00022-1.

- ↑ van Berkum, P.; Sloger, C.; Weber, D. F.; Cregan, P. B.; Keyser, H. H. (1985). "Relationship between Ureide N and N2 Fixation, Aboveground N Accumulation, Acetylene Reduction, and Nodule Mass in Greenhouse and Field Studies with Glycine max L. (Merr)". Plant Physiol. 77 (1): 53–58. doi:10.1104/pp.77.1.53. PMC 1064455

. PMID 16664027.

. PMID 16664027. - ↑ Hennecke, H (1990). "Nitrogen fixation genes involved in the Bradyrhizobium japonicum-soybean symbiosis". FEBS Letters. 268 (2): 422–6. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)81297-2. PMID 2200721.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rivas, Raul; Martens, Miet; De Lajudie, Philippe; Willems, Anne (2009). "Multilocus sequence analysis of the genus Bradyrhizobium☆". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 32 (2): 101–10. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2008.12.005. PMID 19201125.

- ↑ Alberton, O; Kaschuk, G; Hungria, M (2006). "Sampling effects on the assessment of genetic diversity of rhizobia associated with soybean and common bean". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 38 (6): 1298–1307. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.08.018.

- ↑ Salter, S; Cox, M; Turek, E; Calus, S; Cookson, W; Moffatt, M; Turner, P; Parkhill, J; Loman, N; Walker, A (2014). "Reagent contamination can critically impact sequence-based microbiome analyses". BioRxiv. doi:10.1101/007187.

- ↑ Kulakov, L; McAlister, M; Ogden, K; Larkin, M; O'Hanlon, J (2002). "Analysis of Bacteria Contaminating Ultrapure Water in Industrial Systems". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (4): 1548–1555. doi:10.1128/AEM.68.4.1548-1555.2002. PMC 123900

. PMID 11916667.

. PMID 11916667.