Phenoxymethylpenicillin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Veetids |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a685015 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | J01CE02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60% |

| Protein binding | 80% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 30–60 min |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

87-08-1 |

| PubChem (CID) | 6869 |

| DrugBank |

DB00417 |

| ChemSpider |

6607 |

| UNII |

Z61I075U2W |

| KEGG |

D05411 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:27446 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL615 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.566 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

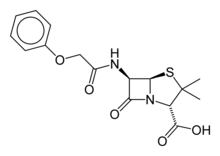

| Formula | C16H18N2O5S |

| Molar mass | 350.39 g/mol |

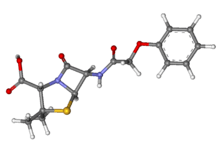

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 120–128 °C (248–262 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenoxymethylpenicillin, commonly known as penicillin V, is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. It is a penicillin that is orally active. It is less active than benzylpenicillin (penicillin G) against Gram-negative bacteria.[1][2] Phenoxymethylpenicillin is more acid-stable than benzylpenicillin, which allows it to be given orally. It exerts a bactericidal action against penicillin-sensitive microorganisms during the stage of active multiplication. It acts by inhibiting the biosynthesis of cell-wall peptidoglycan. It is not active against beta-lactamase-producing bacteria, which include many strains of Staphylococci.[3]

Phenoxymethylpenicillin has a range of antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria that is similar to that of benzylpenicillin and a similar mode of action, but it is substantially less active than benzylpenicillin against Gram-negative bacteria.[1][2]

Phenoxymethylpenicillin is usually used only for the treatment of mild to moderate infections, and not for severe or deep-seated infections since absorption can be unpredictable. Except for the treatment or prevention of infection with Streptococcus pyogenes (which is uniformly sensitive to penicillin), therapy should be guided by bacteriological studies (including sensitivity tests) and by clinical response.[3] Patients treated initially with parenteral benzylpenicillin may continue oral treatment with phenoxymethylpenicillin once a satisfactory clinical response has been obtained.[4]

For prophylaxis against rheumatic fever, phenoxymethylpenicillin given by mouth twice a day is used as an alternative to injections of benzathine penicillin given every three to four weeks. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[5]

Medical uses

Specific indications for phenoxymethylpenicillin include:[4][6]

- Infections caused by Streptococcus pyogenes

- Tonsillitis

- Pharyngitis

- Skin infections

- Anthrax (mild uncomplicated infections)

- Lyme disease (early stage in pregnant women or young children)

- Rheumatic fever (primary and secondary prophylaxis)

- Streptococcal skin infections

- Spleen disorders (pneumococcal infection prophylaxis)

- Initial treatment for Dental Abscesses

- Moderate-to-severe gingivitis (with metronidazole)

- Avulsion injuries of teeth (as an alternative to tetracycline)

- Blood infection prophylaxis in children with sickle cell disease.

Penicillin V is sometimes used in the treatment of odontogenic infections.

Adverse effects

Phenoxymethylpenicillin is usually well tolerated but may occasionally cause transient nausea, vomiting, epigastric distress, diarrhea, constipation, acidic smell to urine and black hairy tongue. A previous hypersensitivity reaction to any penicillin is a contraindication.[3][4]

Compendial status

References

- 1 2 Garrod, L. P. (1960). "Relative Antibacterial Activity of Three Penicillins". British Medical Journal (5172): 527–29.

- 1 2 Garrod, L. P. (1960). "The Relative Antibacterial Activity of Four Penicillins". British Medical Journal (5214): 1695–6.

- 1 2 3 "Penicillin V Potassium tablet: Drug Label Sections". U.S. National Library of Medicine, Daily Med: Current Medication Information. December 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- 1 2 3 Sweetman S., ed. (2002). Martindale: The complete drug reference (Electronic version ed.). London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain and the Pharmaceutical Press.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Rossi S., ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3.

- ↑ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat. "Index (BP 2009)" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2010.