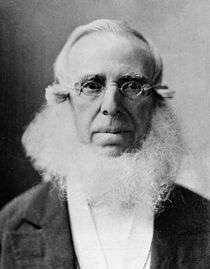

Peter Cooper

| Peter Cooper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

February 12, 1791 New York City, New York |

| Died |

April 4, 1883 (aged 92) New York City, New York |

| Occupation | Industrialist, Inventor, Philanthropist |

| Religion | Unitarian |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Cooper |

| Children |

Edward Cooper Sarah Amelia Cooper |

| Parent(s) | John Cooper and Margaret Campbell |

| Signature | |

| |

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791 – April 4, 1883) was an American industrialist, inventor, philanthropist, and candidate for President of the United States. He designed and built the first American steam locomotive, the Tom Thumb,[1] and founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in Manhattan, New York City.

Early life

Peter Cooper was born in New York City of Dutch, English and Huguenot descent,[2] the fifth child of John Cooper, a Methodist hatmaker from Newburgh, New York [2][3] He worked as a coachmaker's apprentice, cabinet maker, hatmaker, brewer and grocer,[2][4] and was throughout a tinkerer: he developed a cloth-shearing machine which he attempted to sell, as well as an endless chain he intended to be used to pull boats on the Erie Canal, which De Witt Clinton approved of, but which Cooper was unable to sell.[2]

In 1821 Cooper purchased a glue factory on Sunfish Pond for $2,000 in Kips Bay, where he had access to raw materials from the nearby slaughterhouses, and ran it as a successful business for many years,[5] producing a profit of $10,000 (equivalent to roughly $200,000 today) within 2 years, developing new ways to produce glues and cements, gelatin, isinglass and other products, and becoming the city's premier provider to tanners, manufacturers of paints, and dry-goods merchants.[6] The effluent from his successful factory eventually polluted the pond to the extent that in 1839 it had to be drained and refilled.[6]

Business career

Having been convinced that the proposed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad would drive up prices for land in Maryland, Cooper used his profits to buy 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land there in 1828 and began to develop them, draining swampland and flattening hills, during which he discovered iron ore on his property. Seeing the B&O as a natural market for iron rails to be made from his ore, he founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore, and when the railroad developed technical problems, he put together the Tom Thumb steam locomotive for them in 1830 from various old parts, including musket barrels, and some small-scale steam engines he had fiddled with back in New York. The engine was a rousing success, prompting investors to buy stock in B&O, which enabled the company to buy Cooper's iron rails, making him what would be his first fortune.[6]

Cooper began operating an iron rolling mill in New York beginning in 1836, where he was the first to successfully use anthracite coal to puddle iron.[7] Cooper later moved the mill to Trenton, New Jersey on the Delaware River to be closer to the sources of the raw materials the works needed. His son and son-in-law, Edward Cooper and Abram S. Hewitt, later expanded the Trenton facility into a giant complex employing 2,000 people, in which iron was taken from raw material to finished product.[8]

Cooper also operated a successful glue factory in Gowanda, New York that produced glue for decades.[9][10] A glue factory was originally started in association with the Gaensslen Tannery, there, in 1874, though the first construction of the glue factory's plant, originally owned by Richard Wilhelm and known as the Eastern Tanners Glue Company, began on May 5, 1904.[10] Gowanda, therefore, was known as America's glue capital.[10]

Cooper owned a number of patents for his inventions, including some for the manufacture of gelatin, and he developed standards for its production. The patents were later sold to a cough syrup manufacturer who developed a pre-packaged form which his wife named "Jell-O".[11]

Cooper later invested in real estate and insurance, and became one of the richest men in New York City.[12][13] Despite this, he lived relatively simply in an age when the rich were indulging in more and more luxury. He dressed in simple, plain clothes, and limited his household to only two servants; when his wife bought an expensive and elaborate carriage, he returned it for a more sedate and cheaper one. Cooper remained in his home at Fourth Avenue and 28th Street even after the New York and Harlem Railroad established freight yards where cattle cars were parked practically outside his front door, although he did move to the more genteel Gramercy Park development in 1850.[12]

In 1854, Cooper was one of five men who met at the house of Cyrus West Field in Gramercy Park to form the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company, and, in 1855, the American Telegraph Company, which bought up competitors and established extensive control over the expanding American network[14] on the Atlantic Coast and in some Gulf coast states.[15] He was among those supervising the laying of the first Transatlantic telegraph cable in 1858.[16]

.jpg)

Political views and career

In 1840, Cooper became an alderman of New York City.

Prior to the Civil War, Cooper was active in the anti-slavery movement and promoted the application of Christian concepts to solve social injustice. He was a strong supporter of the Union cause during the war and an advocate of the government issue of paper money.

Influenced by the writings of Lydia Maria Child, Cooper became involved in the Indian reform movement, organizing the privately funded United States Indian Commission. This organization, whose members included William E. Dodge and Henry Ward Beecher, was dedicated to the protection and elevation of Native Americans in the United States and the elimination of warfare in the western territories.

Cooper's efforts led to the formation of the Board of Indian Commissioners, which oversaw Ulysses S. Grant's Peace Policy. Between 1870 and 1875, Cooper sponsored Indian delegations to Washington, D.C., New York City, and other Eastern cities. These delegations met with Indian rights advocates and addressed the public on United States Indian policy. Speakers included: Red Cloud, Little Raven, and Alfred B. Meacham and a delegation of Modoc and Klamath Indians.

Cooper was an ardent critic of the gold standard and the debt-based monetary system of bank currency. Throughout the depression from 1873–78, he said that usury was the foremost political problem of the day. He strongly advocated a credit-based, Government-issued currency of United States Notes. In 1883 his addresses, letters and articles on public affairs were compiled into a book, Ideas for a Science of Good Government.[17]

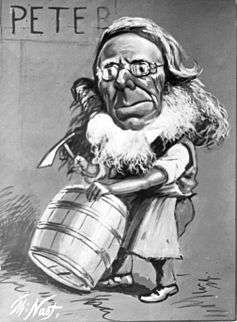

Presidential candidacy

Cooper was encouraged to run in the 1876 presidential election for the Greenback Party without any hope of being elected. His running mate was Samuel Fenton Cary. The campaign cost more than $25,000. At the age of 85 years, Cooper is the oldest person ever nominated by any political party for President of the United States. The election was won by Rutherford Birchard Hayes of the Republican Party. Cooper was surpassed by another unsuccessful candidate: Samuel Jones Tilden of the Democratic Party.

A political family

In 1813, Cooper married Sarah Bedell (1793–1869). Of their six children, only two survived past the age of four years: a son, Edward and a daughter, Sarah Amelia.[18][19] Edward served as Mayor of New York City, as would the husband of Sarah Amelia, Abram S. Hewitt, a man also heavily involved in inventions and industrialization.

Peter Cooper's granddaughters, Sarah Cooper Hewitt, Eleanor Garnier Hewitt and Amy Hewitt Green founded the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, then named the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, in 1895. It was originally part of Cooper Union, but since 1967 has been a unit of the Smithsonian Institution.[20]

Religious views

Cooper was a Unitarian who regularly attended the services of Henry Whitney Bellows, and his views were Universalistic and non-sectarian.[21] In 1873 he wrote:

I look to see the day when the teachers of Christianity will rise above all the cramping powers and conflicting creeds and systems of human device, when they will beseech mankind by all the mercies of God to be reconciled to the government of love, the only government that can ever bring the kingdom of heaven into the hearts of mankind either here or hereafter.[21]

Cooper Union

Cooper had for many years held an interest in adult education: he had served as head of the Public School Society, a private organization which ran New York City's free schools using city money,[22] hen it began evening classes in 1848.[23] Cooper conceived of the idea of having a free institute in New York, similar to the École Polytechnique (Polytechnical School) in Paris, which would offer free practical education to adults in the mechanical arts and science, to help prepare young men and women of the working classes for success in business.

In 1853, he broke ground for the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private college in New York, completing the building in 1859 at the cost of $600,000. Cooper Union offered open-admission night classes available to men and women alike, and attracted 2,000 responses to its initial offering, although 600 later dropped out. The classes were non-sectarian, and women were treated equally with men, although 95% of the students were male. Cooper started a Women's School of Design, which offered daytime courses in engraving, lithography, painting on china and drawing.[23]

The new institution soon became an important part of the community. The Great Hall was a place where the pressing civic controversies of the day could be debated, and, unusually, radical views were not excluded. In addition, the Union's library, unlike the nearby Astor, Mercantile and New York Society Libraries, was open until 10:00 at night, so that working people could make use of them after work hours.[23]

Today Cooper Union[24] is recognized as one of the leading American colleges in the fields of architecture, engineering, and art. Carrying on Peter Cooper's belief that college education should be free, the Cooper Union awarded all its students with a full scholarship until fall 2014.[25]

Philanthropy

In 1851, Cooper was one of the founders of Children's Village, originally an orphanage called "New York Juvenile Asylum", one of the oldest non-profit organizations in the United States.[26]

Death and legacy

Cooper died on April 4, 1883 at the age of 92 and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Aside from Cooper Union, the Peter Cooper Village apartment complex in Manhattan; the Peter Cooper Elementary School in Ringwood, New Jersey; the Peter Cooper Station post office; and Cooper Square in Manhattan are named in his honor.

References

Notes

- ↑ Stover, John F. (1987). History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0-911198-81-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Burrows & Wallace p.563

- ↑ Raymond p.1

- ↑ Raymond p.14

- ↑ Raymond p.19

- 1 2 3 Burrows & Wallace p.564

- ↑ Raymond p.22

- ↑ Burrows & Wallace p.662

- ↑ Community gets gift of Hollywood Theater for restoration, Buffalo News - Southern Tier Edition, Buffalo, NY: Berkshire Hathaway, 16 December 1996, O'Brien, B. | Accessdate 2 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Kirby, C.D. (1976). The Early History of Gowanda and The Beautiful Land of the Cattaraugus. Gowanda, NY: Niagara Frontier Publishing Company, Inc./Gowanda Area Bi-Centennial Committee, Inc.

- ↑ Topper, Robert Q. "Peter Cooper as Chemical Engineer: The Invention of The Gelatin Dessert" on the Cooper Union website

- 1 2 Burrows & Wallace p.725

- ↑ In 1856, Cooper was one of the 9,122 individuals in New York City whose net worth for tax assessment purposes was over $10,000. Burrows & Wallace p.712

- ↑ Burrows & Wallace p.675

- ↑ Harding, Robert S. and Oswald, Alison "Western Union Telegraph Company Records 1820–1995" Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. The American Telegraph Company would eventually, through mergers and buy outs, become part of Western Union.

- ↑ "Local Intelligence.; The Atlantic Telegraph Enterprise. Meeting of Merchants at the Chamber of Commerce—Interesting Addresses by Cyrus W. Field, Peter Cooper, E.E. Morgan, the Mayor, A.A. Low and others—Subscriptions to the Capital Stock of the Company. Peter Cooper's Remarks.". New York Times. March 5, 1863. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

Another great advantage would result from the avoidance of any misunderstanding between Great Britain and the United States – one such prevention would more than pay for the cable.

- ↑ Cooper, Peter (1883). Ideas for a Science of Good Government. In Adddresses, Letters and Articles on a Strictly National Currency, Tariff, and Civil Service. New York: Trow's Printing and Bookbinding Co.

- ↑ Hughes, Thomas (1886). Life and Times of Peter Cooper. London: MACMILLAN AND CO. pp. 222–226. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

Our fifth child was my son Edward, who is still living.[...]My sixth and last child, was our daughter Sarah Amelia, now Mrs. Hewitt.

- ↑ Sarah Cooper (1793–1869). picturehistory.com

- ↑ "About the Museum" on the Cooper-Hewitt website

- 1 2 Cooke, George Willis. Unitarianism in America: A History of Its Origin and Development, v.4 Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1902. pp.408-09

- ↑ Burrows & Wallace p.780

- 1 2 3 Burrows & Wallace p.782

- ↑ Gordon, John. "Peter Cooper". philanthropyroundtable.org. The Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/24/nyregion/cooper-union-to-charge-undergraduates-tuition.html

- ↑ "Our City Charities - No, IIL The New-York Juvenile Asylum.". The New York Times. January 31, 1860. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

Bibliography

- "Cooper, Peter". Mechanical Engineering Biographies Throughout Time. ASME. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999), Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-195-11634-8

- Raymond, Rossiter W. (1901). Peter Cooper. New York: Houghton, Mifflin. Riverside Biographical Series, No. 4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Cooper. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Peter Cooper. |

- Mechanic to Millionaire: The Peter Cooper Story, as seen on PBS Jan. 2, 2011

- Comprehensive Biography by Nathan C. Walker in the Dictionary of Unitarian Universalist Biography

- Facts About Peter Cooper and The Cooper Union

- Information about Peter Cooper from The Cooper Union Library and Archives

- Brief biography

- Find-A-Grave profile for Peter Cooper

- Extensive Information about Peter Cooper

- Images of Peter Cooper's Autobiography

- Peter Cooper's Dictated Autobiography

- The death of slavery by Peter Cooper at archive.org

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by (none) |

Greenback Party presidential candidate 1876 (lost) |

Succeeded by James Baird Weaver |