Ameloblastoma

| Ameloblastoma | |

|---|---|

|

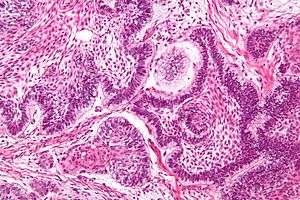

Micrograph of an ameloblastoma showing the characteristic nuclear palisading and stellate reticulum. H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | oncology |

| ICD-10 | D16.4-D16.5 |

| ICD-9-CM | 213.0-213.1 |

| ICD-O | 9310/0 |

| DiseasesDB | 31676 |

| MeSH | D000564 |

Ameloblastoma (from the early English word amel, meaning enamel + the Greek word blastos, meaning germ[1]) is a rare, benign tumor of odontogenic epithelium (ameloblasts, or outside portion, of the teeth during development) much more commonly appearing in the lower jaw than the upper jaw.[2] It was recognized in 1827 by Cusack.[3] This type of odontogenic neoplasm was designated as an adamantinoma in 1885 by the French physician Louis-Charles Malassez.[4] It was finally renamed to the modern name ameloblastoma in 1930 by Ivey and Churchill.[5][6]

While these tumors are rarely malignant or metastatic (that is, they rarely spread to other parts of the body), and progress slowly, the resulting lesions can cause severe abnormalities of the face and jaw. Additionally, because abnormal cell growth easily infiltrates and destroys surrounding bony tissues, wide surgical excision is required to treat this disorder. If an aggressive tumor is left untreated, it can obstruct the nasal and oral airways making it impossible to breathe without oropharyngeal intervention.

Subtypes

There are three main clinical subtypes of ameloblastoma: unicystic, multicystic, peripheral.[7] The peripheral subtype composes 2% of all ameloblastomas.[2] Of all ameloblastomas in younger patients, unicystic ameloblastomas represent 6% of the cases.[2] A fourth subtype, malignant, has been considered by some oncologic specialists, however, this form of the tumor is rare and may be simply a manifestation of one of the three main subtypes. Ameloblastoma also occurs in long bones, and another variant is Craniopharyngioma (Rathke's pouch tumour, Pituitary Ameloblastoma.)

Clinical features

Ameloblastomas are often associated with the presence of unerupted teeth. Symptoms include painless swelling, facial deformity if severe enough, pain if the swelling impinges on other structures, loose teeth, ulcers, and periodontal (gum) disease. Lesions will occur in the mandible and maxilla, although 75% occur in the ascending ramus area and will result in extensive and grotesque deformitites of the mandible and maxilla. In the maxilla it can extend into the maxillary sinus and floor of the nose. The lesion has a tendency to expand the bony cortices because slow growth rate of the lesion allows time for periosteum to develop thin shell of bone ahead of the expanding lesion. This shell of bone cracks when palpated and this phenomenon is referred to as "Egg Shell Cracking" or crepitus, an important diagnostic feature. Ameloblastoma is tentatively diagnosed through radiographic examination and must be confirmed by histological examination (e.g., biopsy). Radiographically, it appears as a lucency in the bone of varying size and features—sometimes it is a single, well-demarcated lesion whereas it often demonstrates as a multiloculated "soap bubble" appearance. Resorption of roots of involved teeth can be seen in some cases, but is not unique to ameloblastoma. The disease is most often found in the posterior body and angle of the mandible, but can occur anywhere in either the maxilla or mandible.

Histopathology

Histopathology will show cells that have the tendency to move the nucleus away from the basement membrane. This process is referred to as "Reverse Polarization". The follicular type will have outer arrangement of columnar or palisaded ameloblast like cells and inner zone of triangular shaped cells resembling stellate reticulum in bell stage. The central cells sometimes degenerate to form central microcysts. The plexiform type has epithelium that proliferates in a "Fish Net Pattern". The plexiform ameloblastoma shows epithelium proliferating in a 'cord like fashion', hence the name 'plexiform'. There are layers of cells in between the proliferating epithelium with a well-formed desmosomal junctions, simulating spindle cell layers.

Variants

The six different histopathological variants of ameloblastoma are desmoplastic, granular cell, basal cell, plexiform, follicular, and acanthomatous.[8]

The acanthomatous variant is extremely rare.[9]

One-third of ameloblastomas are plexiform, one-third are follicular. Other variants such as acanthomatous occur in older patients.[2] In one center, desmoplastic ameloblastomas represented about 9% of all ameloblastomas encountered.[10]

The adenoid variant of ameloblastoma has been recently introduced, but still very rare.[11]

Treatment

While chemotherapy, radiation therapy, curettage and liquid nitrogen have been effective in some cases of ameloblastoma, surgical resection or enucleation remains the most definitive treatment for this condition. In a detailed study of 345 patients, chemotherapy and radiation therapy seemed to be contraindicated for the treatment of ameloblastomas.[2] Thus, surgery is the most common treatment of this tumor. Because of the invasive nature of the growth, excision of normal tissue near the tumor margin is often required. Some have likened the disease to basal cell carcinoma (a skin cancer) in its tendency to spread to adjacent bony and sometimes soft tissues without metastasizing. While not a cancer that actually invades adjacent tissues, ameloblastoma is suspected to spread to adjacent areas of the jaw bone via marrow space. Thus, wide surgical margins that are clear of disease are required for a good prognosis. This is very much like surgical treatment of cancer. Often, treatment requires excision of entire portions of the jaw.

Radiation is ineffective[2] in many cases of ameloblastoma.[12] There have also been reports of sarcoma being induced as the result of using radiation to treat ameloblastoma.[13] Chemotherapy is also often ineffective.[13] However, there is some controversy regarding this[14] and some indication that some ameloblastomas might be more responsive to radiation that previously thought.[15][6]

Molecular biology

There is evidence that suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 may inhibit the local invasiveness of ameloblastoma, however, this was only demonstrated in vitro.[16] There is also some research suggesting that α5β1 integrin may participate in the local invasiveness of ameloblastomas.[17]

A recent study discovered a high frequency of BRAF V600E mutations (15 of 24 samples, 63%) in solid/multicystic ameloblastoma. These data suggests drugs targeting mutant BRAF as potential novel therapies for ameloblastoma.[18]

Recurrence

Recurrence is common, although the recurrence rates for block resection followed by bone graft are lower than those of enucleation and curettage.[19] Follicular variants appear to recur more than plexiform variants.[2] Unicystic tumors recur less frequently than "non-unicystic" tumors.[2] Persistent follow-up examination is essential for managing ameloblastoma.[20] Follow up should occur at regular intervals for at least 10 years.[21] Follow up is important, because 50% of all recurrences occur within 5 years postoperatively.[2] Recurrence within a bone graft (following resection of the original tumor) does occur, but is less common.[22] Seeding to the bone graft is suspected as a cause of recurrence.[20] The recurrences in these cases seem to stem from the soft tissues, especially the adjacent periosteum.[23] Recurrence has been reported to occur as many as 36 years after treatment.[24]

To reduce the likelihood of recurrence within grafted bone, meticulous surgery[22] with attention to the adjacent soft tissues is required.[23][20]

Epidemiology

The annual incidence rates per million for ameloblastomas are 1.96, 1.20, 0.18 and 0.44 for black males, black females, white males and white females respectively.[25] Ameloblastomas account for about one percent of all oral tumors[13] and about 18% of odontogenic tumors.[26] Men and women tend to be equally affected, although women tend to be 4 years younger than men when tumors first occur and tumors appear to be larger in females.[2]

See also

- Ameloblastic fibroma

- Bone grafting

- Epithelial cell rests of Malassez

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Matrix Metalloproteinase-2

- Tooth development and Odontogenesis

References

- ↑ Brazis PW, Miller NR, Lee AG, Holliday MJ (1995). "Neuro-ophthalmologic Aspects of Ameloblastoma". Skull Base Surg. 5 (4): 233–44. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1058921. PMC 1656531

. PMID 17170964.

. PMID 17170964. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Reichart PA; Philipsen HP; Sonner S. (March 1995). "Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases". Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 31B (2): 86–99. PMID 7633291.

- ↑ J.W. Cusack (1827). "Report of the amputations of the lower jaw". Dublin Hosp Rec. 4: 1–38.

- ↑ L. Malassez (1885). "Sur Le role des debris epitheliaux papdentaires". Arch Physiol Norm Pathol. 5: 309–340 6:379–449.

- ↑ R.H. Ivey; H.R. Churchill, (1930). "The need of a standardized surgical and pathological classification of tumors and anomalies of dental origin,". Am Assoc Dent Sch Trans. 7: 240–245.

- 1 2 Madhup, R; Kirti, S; Bhatt, M; Srivastava, M; Sudhir, S; Srivastava, A (January 2006). "Giant ameloblastoma of jaw successfully treated by radiotherapy". Oral Oncology Extra. 42 (1): 22–25. doi:10.1016/j.ooe.2005.08.004.

- ↑ Gardner DG (March 1984). "A pathologist's approach to the treatment of ameloblastoma". J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 42 (3): 161–6. doi:10.1016/S0278-2391(84)80026-9. PMID 6583361.

- ↑ Gruica B; Stauffer E; Buser D; Bornstein M. (April 2003). "Ameloblastoma of the follicular, plexiform, and acanthomatous type in the maxillary sinus: a case report.". Quintessence International. 34 (4): 311–4. PMID 12731620.

- ↑ Vaishali A. Walke; Munshi, Maitreyeem; Raut, Wamanraok; Bobahate, Sudhakark (April 2008). "Cytological diagnosis of acanthmatous ameloblastoma". Journal of Cytology. 25 (2): 62. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.42447.

- ↑ Keszler A, Paparella ML, Dominguez FV (September 1996). "Desmoplastic and non-desmoplastic ameloblastoma: a comparative clinicopathological analysis". Oral Dis. 2 (3): 228–31. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.1996.tb00229.x. PMID 9081764.

- ↑ Ottoman BA, Al-shiaty RA (2016). "Adenoid ameloblastoma with dentinoid and cellular atypia: a rare case report". italian journal of medicine. doi:10.4081/itjm.2016.639.

- ↑ Yan Trokel; Robert Himmelfarb; William Schneider; Robert Hou (3 January 2009). "An Update on the Management of a Recurrent Ameloblastoma: A Case Report and Review of Literature.".

- 1 2 3 Randall S.; Zane, M.D. (3 January 2009). "Maxillary Ameloblastoma". Archived from the original on 2008-07-06.

- ↑ Atkinson CH; Harwood AR; Cummings BJ. (15 February 1984). "Ameloblastoma of the jaw. A reappraisal of the role of megavoltage irradiation". Cancer. 53 (4): 869–73. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840215)53:4<869::AID-CNCR2820530409>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 6420036.

- ↑ Miyamoto CT, Brady LW, Markoe A, Salinger D (June 1991). "Ameloblastoma of the jaw. Treatment with radiation therapy and a case report.". Am J Clin Oncol. 14 (3): 225–30. doi:10.1097/00000421-199106000-00009. PMID 2031509.

- ↑ Anxun Wang; Bin Zhang; Hongzhang Huang; Leitao Zhang; Donglin Zeng; Qian Tao; Jianguang Wang; Chaobin Pan (2008). "Suppression of local invasion of ameloblastoma by inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in vitro". BMC Cancer. 8 (182): 182. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-8-182. PMC 2443806

. PMID 18588710.

. PMID 18588710. - ↑ Souza Andrade ES; da Costa Miguel MC; Pinto LP; de Souza LB. (June 2007). "Ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: the role of alpha2beta1, alpha3beta1, and alpha5beta1 integrins in local invasiveness and architectural characteristics.". Ann Diagn Pathol. 11 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.04.005. PMID 17498594.

- ↑ Kurppa, Kari J; Catón, Javier; Morgan, Peter R; Ristimäki, Ari; Ruhin, Blandine; Kellokoski, Jari; Elenius, Klaus; Heikinheimo, Kristiina (2014). "High frequency of BRAFV600E mutations in ameloblastoma". The Journal of Pathology. 232 (1096-9896): 492–498. doi:10.1002/path.4317. PMC 4255689

. PMID 24374844.

. PMID 24374844. - ↑ Vasan, NT (March 1995). "Recurrent ameloblastoma in an autogenous bone graft after 28 years: a case report". N Z Dent J. 91 (403): 12–3. PMID 7746553.

- 1 2 3 Choi YS; Asaumi J; Yanagi Y; Hisatomi M; Konouchi H; Kishi K. (January 2006). "Recurrence of an ameloblastoma in an autogenous iliac bone graft.". Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 35 (1): 43–6. doi:10.1259/dmfr/13828255. PMID 16421264.

- ↑ Su, T; Liu, B; Zhao, JH; Zhang, WF; Zhao, YF (February 2006). "Ameloblastoma recurrence in the grafted iliac bone: report of three cases". Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. 15 (1): 109–11. PMID 16525625.

- 1 2 Dolan EA; Angelillo JC; Georgiade NG. (April 1981). "Recurrent ameloblastoma in autogenous rib graft. Report of a case.". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 51 (4): 357–60. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(81)90143-2. PMID 7015222.

- 1 2 Martins WD; Fávaro DM. (December 2004). "Recurrence of an ameloblastoma in an autogenous iliac bone graft.". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 98 (6): 657–659. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.04.020. PMID 15583536.

- ↑ Zachariades N. (October 1988). "Recurrences of ameloblastoma in bone grafts. Report of 4 cases.". Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 17 (5): 316–8. doi:10.1016/S0901-5027(88)80011-0. PMID 3143780.

- ↑ Shear M, Singh S (July 1978). "Age-standardized incidence rates of ameloblastoma and dentigerous cyst on the Witwatersrand, South Africa". Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 6 (4): 195–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1978.tb01149.x. PMID 278703.

- ↑ Jonathan Gordon (30 December 2008). "Clinical Quiz: Painless Mass". Appl Radiol Online. 3 (8). Check date values in:

|year= / |date= mismatch(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ameloblastoma. |

- Radiology and Pathology MedPix Image Database