Pechin

The Pechin (親雲上 Peechin, also Peichin) is an Okinawan term for the scholar-officials class of the former Ryūkyū Kingdom (modern-day Okinawa, Japan), the class equivalent of the Japanese Samurai. Though initially culturally different, by the nineteenth century these feudal scholar-officials of the Ryūkyū Kingdom would eventually call themselves samure.

In the last couple hundred years of the existence of the Ryūkyū Kingdom there was a strong push to make Ryūkyū more Japanese, and gradually displace the native language, customs and culture. The once culturally distinct Ryūkyū warrior gradually become more Japanese, to the extent that they adopted Bushido. In Japanese documents from the nineteenth century it is common to find that the Pechin are simply addressed as Samurai, making no distinction to any cultural differences.

Okinawan Caste System

The Pechin were part of a complex caste system that existed in Okinawa for centuries. They were the feudal scholar-officials class that was charged with enforcing the law and providing military defense to the nation, Ryūkyū Kingdom. The specific rank of a samure was noted by the color of his hat.

Okinawan Caste System:

- Royalty - Sho family

- Shizoku (士族 Shizoku) - scholar-officials

- Ueekata or Oyakata (親方 Ueekata) :Lord

- Pechin (親雲上 Peechin)

- Pekumi (親雲上 Peekumī) :upper Pechin

- Satunushi Pechin (里之子親雲上 Satunushi Peechin) :middle Pechin

- Chikudun Pechin (筑登之親雲上 Chikudun Peechin) :lower Pechin

- Satunushi (里之子 Satunushi) :upper page

- Chikudun (筑登之 Chikudun) :lower page

- Heimin (平民 Heimin) - commoners

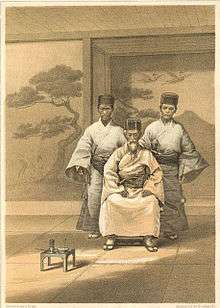

The Pechin class was also responsible for the development of and training in the traditional fighting style, called Ti (Te), which developed into modern-day Karate. The Ryūkyū Pechin kept their fighting techniques secret, usually passing down the most devastating fighting forms to only one member of the family per generation, usually the eldest son. This scholar-official class became part of the caste system in Okinawa. Placed in the upper class, the Pechin would often travel with a servant at their side.

| Status | Residence | Title | Rank | Jīfā (hairpin) | Hachimachi (Hat) | Feudal Title and Estates | Household[1][2] | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royalty | Udun (御殿) |

Ōji | Mu-hon (Supreme) |

Gold | Golden Red Five-color | Aji-jitō (Magiri) |

Dēmyō | 2 | 0.002% | |

| Aji | Red Five-color Yellow Five-color |

26 | 0.032% | |||||||

| Upper Shizoku (Samurē) (Yukatchu) |

Tunchi (殿内) |

Uēkata | Shō-ippon (Senior First Rank) |

Purple Five-color Blue Five-color Purple |

Sō-jitō (Magiri) |

38 | 0.047% | |||

| Ju-ippon (Junior First Rank) |

Purple | |||||||||

| Shō-nipon (Senior Second Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-nipon (Junior Second Rank) |

Gold-silver | Waki-jitō (Village) |

296 | 0.367% | ||||||

| Pēchin | Pēkumī or Pēchin |

Shō-sanpon (Senior Third Rank) |

Silver | Yellow | ||||||

| Ju-sanpon (Junior Third Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shō-yonpon (Senior Fourth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-yonpon (Junior Fourth Rank) |

No | 20,759 | 25.79% | |||||||

| Shizoku (Samurē) (Yukatchu) |

Yā (家) |

Satunushi Pēchin Chikudun Pēchin |

Shō-gohon (Senior Fifth Rank) | |||||||

| Ju-gohon (Junior Fifth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shō-roppon (Senior Sixth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-roppon (Junior Sixth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shō-shichihon (Senior Seventh Rank) | ||||||||||

| Ju-shichihon (Junior Seventh Rank) | ||||||||||

| Satunushi | Shō-happon (Senior Eighth Rank) |

Red | ||||||||

| Ju-happon (Junior Eighth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Chikudun | Shō-kyūhon (Senior Ninth Rank) | |||||||||

| Ju-kyūhon (Junior Ninth Rank) | ||||||||||

| Shī (子) |

No | Copper | Blue / Green | |||||||

| Niya (仁屋) | ||||||||||

| Heimin | Hyakushō (百姓) |

No | Brass | No | No | 59,326 | 73.71% | |||

The Unarmed Ryūkyū scholar-officials

The first time that the Pechin's weapons were confiscated was during the reign of King Shō Shin (1477–1526), who centralized the Ryūkyū Kingdom by forcing the Aji to leave their respective Magiri and move to Shuri. He confiscated weapons from commoners and Pechin who weren't part of the Ryūkyūan military to lower the possibility of rebellion. The second time that the Pechin were disarmed was after the invasion of 1609 by Satsuma Domain, which prohibited the carrying of weapons by the Pechin.

The Pechin were not completely without weapons however. Historians in Okinawa have recovered documents that state that Satsuma outlawed the ownership and sale of firearms in Okinawa, but the Pechin class and above were allowed to keep firearms that were already in their family's possession.

Toshihiro Oshiro, historian and Okinawan martial arts master, states:

There is further documentation that in 1613 the Satsuma issued permits for the Ryūkyū Samure to travel with their personal swords (tachi and wakizashi) to the smiths and polishers in Kagushima, Japan for maintenance and repair. From the issuance of these permits, it is logical to infer that there were restrictions on the Ryūkyū Samure carrying their weapons in public, but it is also clear evidence that these weapons were not confiscated by the Satsuma.

Meiji Period

Undoubtedly the Pechin class was the hardest hit by the changing times. They were the only class that did not have a clear place in the modern world. In 1872, the Japanese Meiji government abolished the Ryūkyū Kingdom and created the Ryūkyū Domain. In 1879, the Meiji government abolished the Ryūkyū Domain and created Okinawa Prefecture.

- Public Proclamation by Chief Secretary Matsuda of Ryūkyū Han

Because the Imperial Decree issued in Meiji 8th year (1875) has not been complied with, the Government was compelled to abolish the feudal clan. The former feudal Lord, his family and kin will be accorded princely treatment, and the persons of citizens, Ryūkyū Samure, their hereditary stipends, property and business interests will be dealt with in a manner as close to traditional customs as is possible. Any acts of maladministration, and exorbitant taxes and dues levied during the regime of the former clan government will probably be righted upon careful consideration. Do not be misled by irresponsible rumors. All are advised to pursue their respective occupations with ease of mind.

The hereditary lords of the Ryūkyū Kingdom were strongly opposed to the complete annexation by Japan, but the Ryūkyūan King forbade the Pechin and aristocrats from fighting the annexation. Ryūkyū submitted to Japan's annexation plans and 300 lords, 2,000 aristocratic families and the king were removed from their positions of power. However, to avoid an armed revolt in Okinawa, as had happened in Japan, special ceremonies were performed for the Pechin class, where they were permitted to honorably accept defeat and ritually cut off their hair (top-knot).

In Okinawa the scholar-official class lost a major source of income in 1903, when massive peasant protest sparked land reforms and the abolition of peasant taxes that sustained the Pechin. Many Pechin found themselves having to reveal their secret unarmed fighting techniques to commoners for income and to keep some element of status. Many Okinawan Karate styles list in their genealogy Karate masters of the Pechin class in the early stages of the style.

Karate

Warfare, law enforcement and fighting systems were the primary business of the warrior class and not the peasant class. Peasants, who often had to perform manual labor for eighteen hours a day to pay taxes to the upper classes and sustain themselves, did not have the energy, time or financial resources to practice the warrior arts. The warrior class, however, which was sustained by peasant taxes could afford the luxury of sending the first born male child of a warrior family to be trained in Ti and other warrior arts.

Okinawan documents will often state that Ti or Kara-Ti was only practiced by the Pechin. However, there are early twentieth-century Japanese documents that mention this secret fighting style as being practiced by the peasants of Okinawa. The disconnect often comes from Japanese ignorance of the Ryūkyūan caste system and at times seeing Okinawans as inferior Japanese. Though, around the time of the creation of the Okinawa Prefecture, the Pechin were calling themselves "Samure"; the word derives from the Japanese term "Samurai".

Shoshin Nagamine (recipient of the Fifth Class Order of the Rising Sun from the Emperor of Japan) states in his book The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do, on pg. 21

- "The forbidden art (Kara-Te) was passed down from father to son among the samure class in Okinawa".

The Okinawa Prefectural Government in recent years has tried to clarify misunderstandings by the West as to the history and development of Karate in Okinawa. The Okinawa Prefectural Government English and Japanese website, Karate and martial arts with weaponry, states that Karate was a secret of the Pechin.

- Okinawan Te was practiced exclusively among the Ryūkyū or Okinawan feudal scholar-officials (Ryūkyū Samure) – Pechin. Peasants were strictly prohibited from practicing or being taught these secret unarmed fighting techniques.

Notes

- ↑ Ryukyu hanshin karoku-ki (琉球藩臣家禄記), National diet library, 1873

- ↑ Okinawa-ken tokei gaihyo (沖縄県統計概表), National diet library, 1876

See also

- Ryūkyū Kingdom

- Okinawa prefecture

- Ryūkyūan people

- Gushiken surname

- Pechin Oyadomari of Tomari

- Pechin Takahara

- Arakaki Seishō

- Pechin Higa

References

- Okinawa, The History of an Island People by George H. Kerr

- The Essence of Okinawan Karate-Do by Shosin Nagamine

- http://www.oshirodojo.com/kobudo_sai.html

- http://calmartialarts.com/karatearticle.shtml

- http://www.wonder-okinawa.jp/023/eng/001/001/index.html#

- http://www.wonder-okinawa.jp/023/eng/003/001/index.html