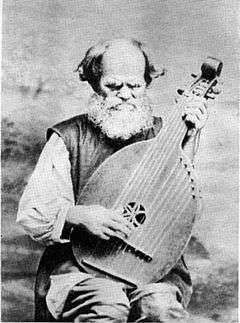

Ostap Veresai

Ostap Mykytovych Veresai (Ukrainian: Остап Микитович Вересай), (1803–1890) was a renowned minstrel and kobzar from the Poltava Governorate (now Chernihiv oblast) of the Russian Empire (in today's Ukraine). He, like no other, helped in the popularity of kobzar art not only in his country, but also outside its borders.

Biography

Childhood

Ostap Veresai was born in the village of Kaliuzhentsi, Pryluky county, Poltava Governorate to a serf family of a blind violinist. Mykyta Veresai, the father, was blind from birth, but was musically very talented and learned to play the violin, which he used in order to earn a living for his family. Mykyta had only one child - Ostap. At the age of 4, the future kobzar became sick and lost his sight.

From an early age Ostap was interested in music and the bandura. As he himself said "...when a kobzar came to my father's house, I would stand near him, and I do not know who was more excited. The kobzar would suggest: 'You Mykyto give this boy to learn, maybe he becomes a kobzar.'"

When Ostap turned 15, his father apprenticed him to a kobzar in a village Berezhivka not far away to his home. Ostap spent only a week with him.

After spending four years at home, Ostap again attempted to undertake studies under a kobzar. A neighbour took him to the market in Romen, where many kobzars would gather, and where Ostap found the kobzar Yefym Andriyshevsky and was formally apprenticed to him for three years.

After the death of Andriyshevsky, Ostap was apprenticed to Semen Koshoviy from the village of Holinka. Ostap spent 9 months with him. He was very strict and exploited the young novice.

In total, Ostap studied for a total of one incomplete year rather than the traditional 3 years.

Popularity

The first folklorist to turn his attention to Ostap was the Russian painter Lev Zhemchuzhnikov. In 1852-56 he spent a considerable time in Ukraine. The painter visited the Galagan estate in Sokyryntsi near Pryluky. Ostap at that time was an inhabitant of Sokyryntsi. He had married. When he met up with Zhemchuzhnikov, they became friends.

In 1871, Galagan took Veresai to Kiev for the opening of the "Pavlo Galagan Collegium" in order to show all his guests the kobzar from Sokyryntsi. Veresai had, up until that moment, only performed in a village setting.

It is possible that it is on this trip Lysenko recorded the melodies of dumy (sung epic poems) and songs which became the basis for his study "The characteristics of musical peculiarities of Ukrainian dumy and songs performed by the kobzar Veresai." The ethnographer P. Chubinsky also recorded almost all of the texts to the songs and dumy which Veresai had in his repertoire.

In 1873, the directors of the Southern Russian division of the Russian Imperial Geographic Society, under the chairmanship of Galagan, met for an unscheduled meeting of the Society - initiated by Galagan - with the goal of introducing Veresai to its members as an example of ancient Ukrainian poetic works. At the meeting the following papers were read:

- Ostap Veresai - one of the last Ukrainian kobzars - by O. Rusov

- The Characteristics of musical peculiarities of Ukrainian dumy and songs performed by the kobzar Veresai" - by Mykola Lysenko.

Those present had the chance to listen to Veresai, who performed the dumy The Escape of the three brothers from Oziv from Turkish Captivity, About Fedir the one without kin, the humorous song Shchyhol and the dance melody Kozachok. In addition to the 28 members of the society, there were 60 invited guests. Much attention was turned to Veresai and it was thought that he was the last of his kind. After this meeting, Veresai performed at a number of other academic conferences.

In 1874 he performed at the IIIrd Archeological Conference in Kiev. The French delegate - Alfred Rambaud, published in an article in one of the Paris journals Ukraine and its historic songs wrote:

One wonderful summer evening we gathered in the University garden to listen to the kobzar; he was seated on a stool, and the listeners, whose numbers continued to grow, sat down around him. One lamp, hiding in the greenery, lit up the face of the kobzar, whose voice sounded clearly like the song of a nightingale ... When Ostap performed one of his humorous songs, it is worth while looking at the way he would dance to the accompaniment of the music, while playing difficult notes on the bandura. The same can be said about the dancing motive, to which he would beat time with his foot; at this time one could take him as a young kozak, watching how he would make knew bends as if doing kozak dances ... His life is different from those Homeric tales. The villager Ostap Veresai is a direct descendant of the ancient Slavonic singers, he is the legal inheritor of the Boyan and other nightingales of the past

Veresai became known in the London magazine "Atheneum". In August 1874 the magazine published an article by the English folklorist and writer Ralston - "The kobzar Veresai, and his music..." In the article, which was written as a review of Rusov's article, Ralston gives Veresai the same role as the rhapsodies of ancient Greece.

In February 1875, Veresai was invited by the ethnographic sector of the Russian Geographical Society to Saint Petersburg. There, apart from performing at a meeting of the Ethnographic sector, he also performed at a meeting of the Painter's guild, at a breakfast which was organized in memory of Taras Shevchenko, and even at the Winter Palace, before Princes Sergey and Pavel Alexandrov.

All the performances of the kobzar were accompanied by full halls and were greeted by the audience with extreme warmth. The Petersburg press wrote positive reviews. The newspaper Novosti wrote:

The singer—a seventy-year-old man, is able to capture the listeners sympathy, and his singing, which is marked by deep artistry and much feeling leaves a deep impression with the listeners. According to the experts, Veresai as a singer, was born with a talent and through his dumas would bring to life ancient Ukraine, with numerous reminiscences of the past[1]

Those who revered Veresai's talent made sure that the Petersburg performances were materially advantageous for him, so that when he returned from Petersburg he was able to build a new larger house for his large family of 15.

Late life and death

Despite his age, retirement was not an option. In the autumn of 1881 and spring of 1882 he traveled to Kiev, and the folklorist K. Ukhach-Oxorovych made a complete recording of his repertoire. This recording in comparison with that made by Pavlo Chubinsky in 1873 showed that the 70-year-old kobzar was able to expand his repertoire with three additional dumy, so that at the beginning of the 80s he had in his repertoire nine dumy:

- Storm on the Black Sea

- The recruitment of the Kozak

- The Escape of the three brothers from Oziv

- The poor widow and her three sons

- The Hawk and the Hawklette

- Fedir the one without Kin

- The Captives lament, son of a widow

- Ivan Konovchenko

Veresai died in April 1890 at the age of 87 in Sokyryntsi.

Cultural impact

Through his performances O. Veresai inspired the creation of a genre known as dumky (small dumy). After his St. Petersburg performances dumky were created by composers Antonín Dvořák, Peter Tchaikovsky, Modest Mussorgsky and a host of other East European composers.

The performances by this blind man in Petersburg also made an impact on the publication of the Ems ukaz in 1876, which banned the publication of books in the Ukrainian language. Paragraph 3 specifically bans the performance of vocal works in the Ukrainian language on stage and this paragraph is accredited to Lysenko's efforts and Veresai's performances in St. Petersburg. Stage performances by kobzars were only allowed again in 1902 after the XIIth Archeological conference.

Books

- Mishalow, V. and M. - Ukrains'ki kobzari-bandurysty - Sydney, Australia, 1986

References

- ↑ Novosti 13 March 1875