Ossessione

| Ossessione | |

|---|---|

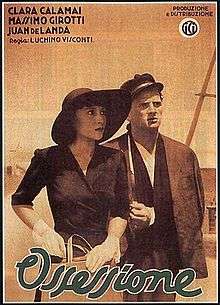

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Luchino Visconti |

| Screenplay by |

Luchino Visconti Mario Alicata Giuseppe De Santis Gianni Puccini |

| Based on |

The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain |

| Starring |

Clara Calamai Massimo Girotti Dhia Cristiani |

| Music by | Giuseppe Rosati |

| Cinematography |

Domenico Scala Aldo Tonti |

| Edited by | Mario Serandrei |

| Distributed by | Industrie Cinematografiche Italiane |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 140 min. |

| Language | Italian |

Ossessione (English: Obsession) is an Italian 1943 film based on the novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, by James M. Cain. Luchino Visconti’s first feature film, it is considered by many to be the first Italian neorealist film, though there is some debate about whether such a categorization is accurate.

Historical context

Working under the censorship of the Fascist Italian government, Visconti encountered problems with the production even before filming commenced. He had initially planned to adapt a story by Giovanni Verga, a renowned Italian realist writer and one of his greatest influences, but it was turned down almost immediately by the Fascist authorities due to its subject matter, which revolved around bandits. Around this time, Visconti uncovered a French translation of Cain’s novel which, famously, had been given to him by French director Jean Renoir while he was working in France in the 1930s.

Visconti adapted the script with a group of men he selected from the Milanese magazine Cinema. The members of this group were talented filmmakers and writers and played a large role in the emerging neorealist movement: Mario Alicata, Gianni Puccini, Antonio Pietrangeli and Giuseppe De Santis. When Ossessione was completed and released in 1943, it was far from the innocent murder mystery the authorities had expected; after a few screenings in Rome and northern Italy, prompting outraged reactions from Fascist and Church authorities, the film was banned by the Fascist government reestablished in the German occupied part of Italy after the September 1943 armistice. Eventually the Fascists destroyed the film, but Visconti managed to keep a duplicate negative from which all existing prints have been made. After the war, Ossessione encountered more problems with mass distribution, this time in the United States. As a result of the wartime production schedule, Visconti had never obtained the rights to the novel and Metro-Goldwyn Mayer began production on another version of the film, directed by Tay Garnett (The Postman Always Rings Twice, 1946), while the Fascist ban on Visconti’s work was still in effect.

Due to the copyright issues, the film didn’t gain distribution outside of Italy until 1976.[1] Despite limited screenings, it gained acclaim among moviegoers who recognized in it some of the same sensibilities they had grown familiar with in neorealist films by Michelangelo Antonioni, Puccini and De Santis, among others.

Plot

The film is the story of a wandering tramp who has an affair with the wife of a restaurant owner. The two then conspire to murder her husband and attempt to live happily ever after. The catch is built into the title of the book, however, and the long arm of the law rings again to disrupt the couple’s already guilt-wracked life, ironically convicting the tramp for an accidental death despite his being absolved of guilt in the actual murder.

Cinematic technique

For the most part, Visconti retained the plot of the novel. He made changes such as tailoring the script to its Italian setting and adding a character, but the main departure from the novel and the defining characteristic of the film is the manner in which it confronts the realities of life.

In one particularly memorable scene that anticipates a major theme of neorealism, Ossessione’s central female character enters her wildly messy kitchen, serves herself a bowl of soup and sits down with a newspaper, only to fall asleep, slumped over wearily in the midst of the confusion.

At several moments like this one, Visconti slows the pace to give the viewer an even more penetrating glimpse into the routine of his characters and, in doing so, roots the narrative squarely in the life of his characters. In another scene, the three are eating when Bregana comments that a local landowner has been shot from behind by a worker, believed to be the result of the worker's love for the landowner's wife. In this way, Visconti foreshadows Bregana’s own death and illuminates the study of class tension that is woven fluidly into the film.

Soon afterwards, Bregana submits to his wife's physical and verbal responses to cats outside crying or due to the heat. He fetches his shotgun and leaves. Shortly after his exit, the adulterous lovers huddle close and hear gunshots, thereby hinting at the doom also reserved for two lovers "in heat."

The landscape itself is realistic, and Visconti takes great care to situate his characters in a rural Italy that remains for the most part unromanticized. Nearly the entire story is told using medium and long shots, with Visconti choosing to employ close-ups only at moments of intense emotion. Characters are depicted interacting with and moving around within their environment; to this effect, Visconti favors long and ponderous shots while making use of depth of focus to highlight the variety of action occurring throughout the space of the frame.

He resists identifying solely with one character and prefers instead to maintain a distance, taking them all in with his viewfinder as independent but irrevocably tangled components of a larger cast, which includes the sets, scenery and landscape as well as what goes on outside of the frame. Shots of the landscape largely consist of the dusty road winding into the distance and the interior shots are just as bleak; the dowdy kitchen exudes a nearly tangible film of dust and grime and the dingy hotel room that speaks, with each detail, of the rebellious freedom cherished by those who share it. The shift of focus from the novel is clear even in Visconti’s decision to change the title.

Whereas the novel’s title alludes to the final retribution exacted upon the adulterous couple, Visconti’s header bespeaks the focus of his film, obsessive passion.

Despite arguments about how to define neorealist cinema, certainly one of Ossessione’s most poignant aspects is its stark realism. Despite being popular actors of Italian cinema, the stars of the film, Massimo Girotti and Clara Calamai, deliver breathtaking performances that are anything but glamorous. The lovers, Gino and Giovanna, played by Girotti and Calamai, first meet in the kitchen of the inn that Giovanna runs with her husband, the fat and dim-witted Bregana. It is in the symbolic and literal center of the family sphere, before they ever touch, that the two make a silent oath. Their love, tainted as it is by a lie, is difficult for either of them to bear and the tension is only exacerbated by Bregana’s overwhelming presence.

Unable to continue the affair under such pretense but genuinely in love, Gino tries to persuade Giovanna to leave with him. She is clearly tempted but knows of the power the road has over Gino, a relationship that Visconti executes nearly as palpably as that between him and Giovanna. She ultimately refuses Gino, opting for the security and stability that Bregana has to offer, and he sets out once again unencumbered. When they cross paths some time later, it is in the city and Bregana is extremely drunk, engaged in a singing competition. Against the backdrop of the drunken and foolish Bregana, the couple plans his death, an act they carry out in a car crash.

Rather than granting them the freedom they so desperately seek, however, the murder only heightens the need for deception and makes more acute the guilt they had previously been dealing with. Despite Giovanna’s attempt to construct a normal life with Gino, Bregana’s presence seems to remain long after they return to the inn.

Their already crumbling relationship reaches its bounds when they go to collect the money from Bregana's life insurance policy. They have a very hostile argument and Gino retaliates by engaging Anita, an attractive young prostitute. Though Giovanna is pregnant and there seems to be some hope for the couple, Gino is left alone to deal with the law when Giovanna is killed in the film’s second car crash.

The character of lo Spagnolo (the Spaniard), Visconti's main textual departure from the novel, plays a pivotal role in the story of Ossessione. After failing to convince Giovanna to flee with him, Gino meets Spagnolo after boarding a train to the city and the two of them strike up an instant friendship, subsequently working and living together. Spagnolo is an actor who works as a street vendor and serves as a foil to Giovanna's traditionalism and inability to let go of the material lifestyle. In contrast to the other main characters, who come across as very real and thoroughly developed, Spagnolo operates chiefly on a symbolic level. He represents for Gino the possibility of a liberated masculinity living a life successfully separate from society’s impositions, an alternative to the life he is drawn toward in his relationship with Giovanna.

Both Giovanna and Gino are tragic characters in their inability to find a space in which to situate themselves comfortably. The limited roles made available by society prove to be insufficient in providing narratives for their lives that bring them closer to happiness. Giovanna is pulled away from the security of her marriage to the repulsive Bregana by a desire for true love and fulfillment, whose potential is actualized with the appearance of Gino. Her attempts to hold onto the fortune which came with marriage, however, ultimately lead to the failure of their relationship and perhaps, by extension, her death. Gino’s situation seems to be just as distinct, if not more so, as the force pulling him away from Giovanna is his fear of a traditional commitment. From the first time that they sleep together, after which Giovanna shares with Gino all of her deepest problems while he listens to the sound of waves in a seashell, it is clear that he answers only to the open road, identifying it as his alternative to becoming an active part of mainstream society. Spagnolo is the road manifest, masculine freedom in opposition to Giovanna’s femininity, love and family values. Caught in between the two conflicting ideals, Gino ends up violating both of them and dooming himself in the process.

Visconti's approach to filmmaking is very structured and he provides several pairs of parallel events, such as the car crashes. Gino meets Spagnolo as they sit side by side on a wall, a scene that is repeated at the end of their friendship; similarly, Gino angrily leaves Giovanna by the side of the road and is later abandoned by Spagnolo in a parallel scene. Cinematic techniques, such as the instances in which Visconti foreshadows major plot twists or the introduction of Spagnolo as a counterweight, demonstrate Visconti’s formalist streak and technical virtuosity, but his realist vision and taste for drama are truly what breathe life into Ossessione.

See also

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

Sources

- ↑ "A Short History of Film". google.be. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

Further reading

- Bacon, Henry, Visconti: Explorations of Beauty and Decay, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Bondanella, Peter E., Italian Cinema: From Neorealism to the Present, New York: Continuum, 2001.

- Korte, Walter F., Jr. “Marxism and Formalism in the Films of Luchino Visconti”, Cinema Journal, Vol. 11, No. 1, Autumn, 1971, pp. 2–12.

- Lopate, Phillip. “The Operatic Realism of Luchino Visconti”, Totally, Tenderly, Tragically: Essays and Criticism From a Lifelong Love Affair with the Movies, New York: Anchor Books, 1998. pp. 101–114

- Nochimson, Martha P., “The Melodramatic Neorealism of Luchino Visconti”, Cineaste, Vol. 28, No. 2, Spring, 2003, pp. 45–48.

- Pacifici, Sergio J., “Notes Toward a Definition of Neorealism”, Yale French Studies, No. 17, Art of the Cinema, 1956, pp. 44–53. Pacifici discusses the term Neorealism and examines several popular movies which came out of the movement.

- Poggi, Gianfranco, “Luchino Visconti and the Italian Cinema”, Film Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 3, Spring, 1960, pp. 11–22. Poggi discusses Visconti and his work in the context of neorealism and the Italian cinema of the time.

- Servadio, Gaia, Visconti: A Biography, New York: F. Watts, 1983.

- Shiel, Mark, Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City, Wallflower Press, 2005 ISBN 978-1-904764-48-9 ISBN 1904764487

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ossessione. |

- Ossessione at the Internet Movie Database

- Ossessione at Entrada Franca (Portuguese)