Orphanage

An orphanage is a residential institution devoted to the care of orphans—children whose biological parents are deceased or otherwise unable or unwilling to care for them. Biological parents, and sometimes biological grandparents, are legally responsible for supporting children, but in the absence of these, no named godparent, or other relatives willing to care for the children, they become a ward of the state, and orphanages are one way of providing for their care, housing and education.

It is frequently used to describe institutions abroad, where it is a more accurate term, since the word orphan has a different definition in international adoption.[1] Most children who live in orphanages are not orphans; four out of five children in orphanages having at least one living parent and most having some extended family.[2] Most orphanages have been closed in Europe and North America. There remain a large number of state funded orphanages in the former Soviet Bloc but they are slowly being phased out in favour of direct support to vulnerable families and the development of foster care and adoption services where this is not possible.

Few large international charities continue to fund orphanages; however, they are still commonly founded by smaller charities and religious groups.[3] Especially in developing countries, orphanages may prey on vulnerable families at risk of breakdown and actively recruit children to ensure continued funding. Orphanages in developing countries are rarely run by the state.[3][4]

Other residential institutions for children can be called group homes, children's homes, refuges, rehabilitation centers, night shelters, or youth treatment centers.

History

The Romans formed their first orphanages around 400 AD. Jewish law prescribed care for the widow and the orphan, and Athenian law supported all orphans of those killed in military service until the age of eighteen. Plato (Laws, 927) says: "Orphans should be placed under the care of public guardians. Men should have a fear of the loneliness of orphans and of the souls of their departed parents. A man should love the unfortunate orphan of whom he is guardian as if he were his own child. He should be as careful and as diligent in the management of the orphan's property as of his own or even more careful still."[5] The care of orphans was referred to bishops and, during the Middle Ages, to monasteries. As soon as they were old enough, children were often given as apprentices to households to ensure their support and to learn an occupation.

In medieval Europe, care for orphans tended to reside with the Church. The Elizabethan Poor Laws were enacted at the time of the Reformation, and placed public responsibility on individual parishes to care for the indigent poor.

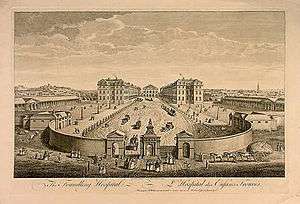

Foundling Hospitals

The growth of sentimental philanthropy in the 18th century, led to the establishment of the first charitable institutions catering for the orphan. The Foundling Hospital was founded in 1741 by the philanthropic sea captain Thomas Coram in London, England, as a children's home for the "education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children." The first children were admitted into a temporary house located in Hatton Garden. At first, no questions were asked about child or parent, but a distinguishing token was put on each child by the parent.[6]

On reception, children were sent to wet nurses in the countryside, where they stayed until they were about four or five years old. At sixteen, girls were generally apprenticed as servants for four years; at fourteen, boys were apprenticed into variety of occupations, typically for seven years. There was a small benevolent fund for adults.

In 1756, the House of Commons resolved that all children offered should be received, that local receiving places should be appointed all over the country, and that the funds should be publicly guaranteed. A basket was accordingly hung outside the hospital; the maximum age for admission was raised from two months to twelve, and a flood of children poured in from country workhouses. Parliament soon came to the conclusion that the indiscriminate admission should be discontinued. The hospital adopted a system of receiving children only with considerable sums. This practice was finally stopped in 1801; and it henceforth became a fundamental rule that no money was to be received.[7]

19th century

By the early nineteenth century, the problem of abandoned children in urban areas, especially London, began to reach alarming proportions. The workhouse system, instituted in 1834, although often brutal, was an attempt at the time to house orphans as well as other vulnerable people in society who could not support themselves in exchange for work. Conditions, especially for the women and children, were so bad as to cause an outcry among the social reform-minded middle-class; some of Charles Dickens' most famous novels, including Oliver Twist, highlighted the plight of the vulnerable and the often abusive conditions that were prevalent in the London orphanages.

Clamour for change led to the birth of the orphanage movement. The movement really took off in the mid-19th century although orphanages such as the Orphan Working Home in 1758 and the Bristol Asylum for Poor Orphan Girls in 1795, had been set up earlier. Private orphanages were founded by private benefactors; these often received royal patronage and government oversight.[8] Ragged schools, founded by John Pounds and the Lord Shaftesbury were also set up to provide pauper children with basic education. Orphanages were also set up in the United States from the early 19th century, although under the influence of Charles Loring Brace, foster care became a popular alternative from the mid-19th century.[9] The Social Security Act of 1935 improved social security, by authorising Aid to Dependent Children (ADC).

A very influential philanthropist of the era was Thomas John Barnardo, the founder of the charity Barnardos. Becoming aware of the great numbers of homeless and destitute children adrift in the cities of England and encouraged by the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury and the 1st Earl Cairns, he opened the first of the "Dr Barnardo’s Homes" in 1870. By his death in 1905, he had established 112 district homes, which searched for and received waifs and strays, to feed, clothe and educate them.[10] The system under which the institution was carried on is broadly as follows: the infants and younger girls and boys were chiefly "boarded out" in rural districts; girls above fourteen years of age were sent to the industrial training homes, to be taught useful domestic occupations; boys above seventeen years of age were first tested in labour homes and then placed in employment at home, sent to sea, or emigrated; boys of between thirteen and seventeen years of age were trained for the various trades for which they might be mentally or physically fitted.[10]

Deinstitutionalisation

The Deinstitutionalisation of orphanages and childrens homes programme began in the 1950s, after a series of scandals involving the coercion of birth parents and abuse of orphans (notably at Georgia Tann's Tennessee Children's Home Society). Many countries accepted the need to de-institutionalize the care of vulnerable children—that is, close down orphanages in favor of foster care and accelerated adoption. Moreover, as it is no longer common for birth parents in Western countries to give up their children, and as far fewer people die of diseases or violence while their children are still young, the need to operate large orphanages has decreased.

Major charities are increasingly focusing their efforts on the re-integration of orphans in order to keep them with their parents or extended family and communities. Orphanages are no longer common in the European community, and Romania in particular has struggled to reduce the visibility of its children's institutions to meet conditions of its entry into the European Union.

It is important to understand the reasons for child abandonment, then set up targeted alternative services to support vulnerable families at risk of separation[11] such as mother and baby units and day care centres.[12]

Comparison to alternatives

There is an increasing body of evidence that orphanages, especially large orphanages, are the worst possible care option for children.[13][14] In large institutions all children, but particularly babies may not receive enough eye contact, physical contact, and stimulation to promote proper physical, social or cognitive development.[15][16] In the worst cases, orphanages can be dangerous and unregulated places where children are subject to abuse and neglect.[13][17][18]

There is only one significant study which disputes this. It was carried out by Duke University. Their researchers concluded that institutional care in America in the 20th century produced the same health, emotional, intellectual, mental, and physical outcomes as care by relatives, and better than care in the homes of strangers.[19] One explanation for this is the prevalence of permanent temporary foster care. This is the name for a long string of short stays with different foster care families.[19] Permanent temporary foster care is highly disruptive to the child and prevents the child from developing a sense of security or belonging. Placement in the home of a relative maintains and usually improves the child's connection to family members.[19][20]

Whereas orphanages are intended to be reasonably permanent placements, group homes may be used for short-term placements. They may be residential treatment centers, and they frequently specialize in a particular population with psychiatric or behavioral problems, e.g., a group home for children and teens with autism, eating disorders, or substance abuse problems or child soldiers undergoing decommissioning.

Criticism

Most of the children living in institutions around the world have a surviving parent or close relative, and they most commonly entered orphanages because of poverty.[21] It is speculated that, flush with money, orphanages are increasing and push for children to join even though demographic data show that even the poorest extended families usually take in children whose parents have died.[21] Experts and child advocates maintain that orphanages are expensive and often harm children's development by separating them from their families and that it would be more effective and cheaper to aid close relatives who want to take in the orphans.[21]

Scams

Visitors to developing countries can be taken in by orphanage scams, which can include orphanages created for the day[22] or orphanages set up as a front to get foreigners to pay school fees of orphanage directors' extended families.[23] Alternatively the children whose upkeep is being funded by foreigners may be sent to work, not to school, the exact opposite of what the donor is expecting.[24] The worst even sell children.[25][26][27] In Cambodia some are bought from their parents for very little and passed on to westerners who pay a large fee to adopt them.[28] This also happens in China.[29] In Nepal, orphanages can be used as a way to remove a child from their parents before placing them for adoption overseas, which is equally lucrative to the owners who receive a number of official and unofficial payments and "donations".[30][31] In other countries, such as Indonesia, orphanages are run as businesses, which will attract donations and make the owners rich; often the conditions orphans are kept in will deliberately be poor to attract more donations.[32]

Worldwide

Europe

The orphanages and institutions remaining in Europe tend to be in Eastern Europe and are generally state-funded.

Albania

There are approximately 10 small orphanages in Albania; each one having only 12-40 children residing there.[33]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

SOS Children's Villages giving support to 240 orphaned children.[34]

Bulgaria

The Bulgarian government has shown interest in strengthening children's rights.

In 2010, Bulgaria adopted a national strategic plan for the period 2010–2025 to improve the living standards of the country's children. Bulgaria is working hard to get all institutions closed within the next few years and find alternative ways to take care of the children.

Support is sporadically given to poor families and work during daytime; correspondingly, different kinds of day centers have started up, though the quality of care in these centers is poorly measured and difficult to monitor. A smaller number of children have also been able to be relocated into foster families".[35][36]

There are 7000[36] children living in Bulgarian orphanages wrongly classified as orphaned. Only 10 percent of these are orphans, with the rest of the children placed in orphanages for temporary periods when the family is in crisis.[37]

Estonia

As of 2009, there are 35 orphanages, which houses approximately 1300 orphaned children.[38][39]

Hungary

A comprehensive national strategy for strengthening the rights of children was adopted by Parliament in 2007 and will run until 2032.

Child flow to orphanages has been stopped and children are now protected by social services. Violation of children's rights leads to litigation.[40]

Lithuania

In Lithuania there are 105 institutions. 41 percent of the institutions each have more than 60 children. Lithuania has the highest number of orphaned children in Northern Europe.[41][42]

Poland

Children's rights enjoys a relatively strong protection in Poland. Orphaned children are now protected by social services.

Social Workers' opportunities have increased by establishing more foster homes and aggressive family members can now be forced away from home, instead of re-placing the child/children.[43]

Moldova

More than 8800 children are being raised in state institutions, but only three percent of them are orphans.[44]

Romania

The Romanian child welfare system is in the process of being revised and has reduced the flow of infants into orphanages.[45]

According to Baroness Emma Nicholson, in some counties Romania now has "a completely new, world class, state of the art, child health development policy." Dickensian orphanages remain in Romania,[46] but by 2020 Romanian institutions are to be replaced by family care services, as children in need will be protected by social services.[47]

As of 2011, there are 10,833 orphaned children in 256 large institutions in Romania.[48]

| # | year | Total children in care of the state. | Number of children in orphanages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1990 | 47,405[49] | |

| 2. | 1994 | 52,986[49] | |

| 3. | 1997 | 51,468 | 39,569 |

| 4. | 1998 | 55,641 | 38,597 |

| 5. | 1999 | 57,087 | 33,356 |

| 6. | 2000 | 87,753 | 57,181[50] |

| 7. | 2001 | 78,000 | 47,171 |

| 8. | 2002 | 87,867 | 49,965[51] |

| 9. | 2003 | 86,379 | 43,092[52] |

| 10. | 2004 | 84,445 | 37,660[53] |

| 11. | 2005 | 83,059 | 32,821[54] |

| 12. | 2006 | 78,766 | 28,786 |

| 13. | 2007 | 73,793 | 26,599[55] |

| 14. | 2008 | 71,047 | 24,979[56] |

| 15. | 2009 | 68,858 | 24,227[57] |

| 16. | 2010 | 62,000 | 19,000[48][58] |

| 17. | 2011 | 50,000 | 10,833[47] |

The large jump in children protected by the state in 2000 over 1999 is because many children's hospital and residential schools for small children were re-designated as orphanages in the year 2000.

Serbia

There are many state orphanages "where several thousand children are kept and which are still part of an outdated child care system". The conditions for them are bad because the government does not pay enough attention in improving the living standards for disabled children in Serbia's orphanages and medical institutions.[60]

Slovakia

The Committee made recommendations, such as proposals for the adoption of a new "national 14" action plan for children for at least the next five years, and the creation of an independent institution for the protection of child rights.[61]

Sweden

In Sweden there are 5,000 children in the care of the state. None of them are currently living in an orphanage, because there is a social service law which requires that the children reside in a family home.

United Kingdom

During the Victorian Era, child abandonment was rampant, and orphanages were set up to reduce infant mortality. Such places were often so full of children that "killing nurses" often administered Godfrey's Cordial, a special concoction of opium and treacle, to soothe baby colic.[62]

Orphaned children were placed in either prisons or the poorhouse/workhouse, as there were so few places in orphanages, or else they were left to fend for themselves on the street. Such places as were available could only be obtained by procuring votes for admission, placing them out of reach of poor families.

Known orphanages are:

| Founded in | Name | Location | Founder |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1741 | Foundling Hospital | London | Thomas Coram |

| 1795 | Bristol Asylum for Poor Orphan Girls (Blue Maids' Orphanage) | nr Stokes Croft turnpike, Bristol | |

| 1800 | St Elizabeth's Orphanage of Mercy | Eastcombe, Glos | |

| 1813 | London Asylum for Orphans

|

Hackney, London | Rev Andrew Reed |

| 1822 | Female Orphan Asylum | Brighton | Francois de Rosaz |

| 1827 | Infant Orphan Asylum

|

Wanstead | Rev Andrew Reed |

| 1829 | Sailor Orphan Girls School | London | |

| 1831 | Jews' Orphan Asylum

|

Goodmans Fields, Whitechapel, London 1831

|

|

| 1836 | Ashley Down orphanage | Bristol | George Müller |

| 1844 | Asylum for Fatherless Children | Richmond | Rev Andrew Reed |

| 1854 | Wolverhampton Orphan Asylum | Goldthorn Hill, Wolverhampton | John Lees |

| 1856 | Wiltshire Reformatory | Warminster | |

| 1860 | Major Street Ragged Schools | Liverpool | Canon Thomas Major Lester |

| 1861 | St. Philip Neri's orphanage for boys | Birmingham | Oratorians |

| 1861 | Adult Orphan Institution | St Andrew's Place, Regent's Park, London | |

| 1861 | British Orphan Asylum | Clapham, London | |

| 1861 | Female Orphan Asylum | Westminster Road, London | |

| 1861 | Female Orphan Home | Charlotte Row, St Peter Walworth, London | |

| 1861 | Merchant Seamen's Orphan Asylum | Bromley St Leonard, Bow, London | |

| 1861 | Orphan Working School | Haverstock Hill, Kentish Town, London | |

| 1861 | Orphanage | Eagle House, Hammersmith, London | |

| 1861 | The Orphanage Asylum | Christchurch, Marylebone, London | |

| 1861 | The Sailors' Orphan Girls' School & Home | Hampstead, London | |

| 1861 | Sunderland Orphan Asylum | Sunderland | |

| 1862 | Swansea Orphan Home for Girls | Swansea | |

| 1863 | British Seaman’s Orphan Boys' Home | Brixham | William Gibbs |

| 1865 | The Boys' Home Regent's Park | London | |

| 1866 | Dr Barnardo's | various | Dr Thomas Barnardo |

| 1866 | National Industrial Home for Crippled Boys | London | |

| 1867 | Peckham Home for Little Girls | London | Maria Rye |

| 1868 | The Boys' Refuge | Bisley | |

| 1868 | Royal Albert Orphanage | Worcester | |

| 1868 | Worcester Orphan Asylum | Worcester | |

| 1868 | St Francis' Boy's Home | Shefford, Bedfordshire | |

| 1869 | Ely Deaconesses Orphanage | Bedford | Rev Thomas Bowman Stephenson |

| 1869 | Orphanage and Almshouses | Erdington | Josiah Mason |

| 1869 | The Neglected Children of Exeter | Exeter | |

| 1869 | Alexandra Orphanage for Infants | Hornsey Rise, London | |

| 1869 | Stockwell Orphanage | London | Charles Spurgeon |

| 1869 | New Orphan Asylum | Upper Henwick, Worcs | |

| 1869 | Wesleyan Methodist National Children's Homes

|

various | Rev Thomas Bowman Stephenson |

| 1870 | Fegans Homes | London | James William Condell Fegan |

| 1870 | Manchester and Salford Boys' and Girls' Refuge | Manchester | |

| 1870 | 18 Stepney Causeway

|

London

|

Dr Barnardo |

| 1871 | Wigmore | West Bromwich and Walsall | WJ Gilpin |

| 1872 | Middlemore Home | Edgbaston | Dr John T. Middlemore |

| 1872 | St Theresa Roman Catholic Orphanage for Girls | Plymouth | Sisters of Charity |

| 1873 | The Orphan Homes | Ryelands Road, Leominster | Henry S. Newman[63][64] |

| 1874 | Cottage Homes for Children | West Derby | Mrs Nassau Senior |

| 1875 | Aberlour Orphanage | Aberlour, Scotland | Rev Charles Jupp |

| 1877 | All Saints Boys' Orphanage | Lewisham, London | |

| 1880 | Birmingham Working Boy's Home (for boys over the age of 13) | Birmingham | Major Alfred V. Fordyce |

| 1881 | The Waifs and Strays' Society[65]

|

East Dulwich, London | Edward de Montjoie Rudolf |

| 1881 | Catholic Childrens Protection Society | Liverpool | James Nugent & Bishop Bernard O'Reilly |

| 1881 | Dorset County Boys Home | Milborne St Andrew | |

| 1881 | Brixton Orphanage | Brixton Road, Lambeth, London | |

| 1881 | Orphanage Infirmary | West Square, London Road, Southwark, London | |

| 1881 | Orphans' Home | South Street. London Road, Southwark, London | |

| 1882 | St Michael's Home for Friendless Girls | Salisbury | |

| 1890 | St Saviour's Home | Shrewsbury | |

| 1890 | Orphanage of Pity | Warminster | |

| 1890 | Wolverhampton Union Cottage homes | Wolverhampton | |

| 1892 | Calthorpe Home For Girls | Handsworth, Birmingham | The Waifs and Strays' Society[66] |

| 1899 | Northern Police Orphanage | Harrogate | Miss Catherine Gurney |

| 1899 | Inglewood Children's Home | Otley, Leeds | |

| 1918 | Painswick Orphanage | Painswick | |

| unknown | Clio Boys' Home | Liverpool | |

| unknown | St Philip's Orphanage, (RC Institution for Poor Orphan Children) | Brompton, Kensington |

Sub-Saharan Africa

The majority of African orphanages (especially in Sub-Saharan Africa) appear to be funded by donors, often from Western nations, rather than by domestic governments.

Ethiopia

"For example, in the Jerusalem Association Children's Home (JACH), only 160 children remain of the 785 who were in JACH's three orphanages." / "Attitudes regarding the institutional care of children have shifted dramatically in recent years in Ethiopia. There appears to be general recognition by MOLSA and the NGOs with which Pact is working that such care is, at best, a last resort, and that serious problems arise with the social reintegration of children who grow up in institutions, and deinstitutionalization through family reunification and independent living are being emphasized."[67]

Ghana

A 2007 survey sponsored by OAfrica (previously OrphanAid Africa) and carried out by the Department of Social Welfare came up with the figure of 4,800 children in institutional care in 148 orphanages.[68] The government is currently attempting to phase out the use of orphanages in favor of foster care placements and adoption. At least eighty-eight[69] homes have been closed since the passage of the National Plan of Action for Orphans and Vulnerable Children. The website www.ovcghana.org details these reforms.

Kenya

A 1999 survey of 36,000 orphans found the following number in institutional care: 64 in registered institutions and 164 in unregistered institutions.[70]

Malawi

There are about 101 orphanages in Malawi. There is a UNICEF/Government driven program on de-institutionalisation, but few orphanages are yet involved in the program.

Rwanda

Out of 400,000 orphans, 5,000 are living in orphanages.[71] The Government of Rwanda are working with Hope and Homes for Children to close the first institution and develop a model for community-based childcare which can be used across the country and ultimately Africa[72]

Tanzania

"Currently, there are 52 orphanages in Tanzania caring for about 3,000 orphans and vulnerable children."[73] A world bank document on Tanzania showed it was six times more expensive to institutionalise a child there than to help the family become functional and support the child themselves.

Nigeria

In Nigeria, a rapid assessment of orphans and vulnerable children conducted in 2004 with UNICEF support revealed that there were about seven millions orphans in 2003 and that 800,000 more orphans were added during that same year. Out of this total number, about 1.8 million are orphaned by HIV/AIDS. With the spread of HIV/AIDS, the number of orphans is expected to increase rapidly in the coming years to 8.2 million by 2010.[74]

South Africa

Since 2000, South Africa does not license orphanages any more but they continue to be set up unregulated and potentially more harmful. Theoretically the policy supports community-based family homes but this is not always the case. One example is the homes operated by Thokomala.[75]

Zambia

A 1996 national survey of orphans revealed no evidence of orphanage care. The breakdown of care was as follows: 38% grandparents 55% extended family 1% older orphan 6% non-relative Recently a group of students started a fundraising website for an orphanage in Zambia.[70][76]

Zimbabwe

There are 39 privately run children's charity homes, or orphanages, in the country, and the government operates eight of its own. Privately run Orphanages can accommodate an average of 2000 children, though some are very small and located in very remote areas, hence can take in less than 150 children. Statistics on the total number of children in orphanages nationwide are unavailable, but caregivers say their facilities were becoming unmanageably overwhelmed almost on a daily basis. Between 1994 and 1998, the number of orphans in Zimbabwe more than doubled from 200,000 to 543,000, and in five years, the number is expected to reach 900,000. (Unfortunately, there is no room for these children.)[77]

Togo

In Togo, there were an estimated 280,000 orphans under 18 years of age in 2005, 88,000 of them orphaned by AIDS.[78][78] Ninety-six thousand orphans in Togo attend school.[78]

Sierra Leone

- Children (0–17 years) orphaned by AIDS, 2005, estimate 31,000[80]

- Children (0–17 years) orphaned due to all causes, 2005, estimate 340,000[80]

- Orphan school attendance ratio, 1999–2005 71,000[80]

Senegal

- Children (0–17 years) orphaned by AIDS, 2005, estimate 25,000[81]

- Children (0–17 years) orphaned due to all causes, 2005, estimate 560,000[81]

- Orphan school attendance ratio, 1999–2005 74,000[81]

South Asia

Nepal

There are at least 602 child care homes housing 15,095 children in Nepal[82] "Orphanages have turned into a Nepalese industry there is rampant abuse and a great need for intervention."[27][83] Many do not require adequate checks of their volunteers, leaving children open to abuse.[82]

Afghanistan

.jpg)

"At Kabul's two main orphanages, Alauddin and Tahia Maskan, the number of children enrolled has increased almost 80 percent since last January, from 700 to over 1,200 children. Almost half of these come from families who have at least one parent, but who can't support their children."[84] The non-governmental organisation Mahboba's promise assists orphans in contemporary Afghanistan.[85] Nowadays the number of orphanages had changed. There are approximately 19 orphanages only in Kabul.[86]

Bangladesh

"There are no statistics regarding the actual number of children in welfare institutions in Bangladesh. The Department of Social Services, under the Ministry of Social Welfare, has a major programme named Child Welfare and Child Development in order to provide access to food, shelter, basic education, health services and other basic opportunities for hapless children." (The following numbers mention capacity only, not actual numbers of orphans at present.)

9,500 – State institutions 250 – babies in three available "baby homes" 400 – Destitute Children's Rehabilitation Centre 100 – Vocational Training Centre for Orphans and Destitute Children 1,400 -Sixty-five Welfare and Rehabilitation Programmes for Children with Disability

The private welfare institutions are mostly known as orphanages and madrassahs. The authorities of most of these orphanages put more emphasis on religion and religious studies. One example follows: 400 – Approximately – Nawab Sir Salimullah Muslim Orphanage.[87]

Maldives

Orphans, Children (0–17 years) orphaned due to all causes, 2010, estimate 51.[88]

India

.jpg)

India has a very large number of orphans as well as destitute child population. Orphanages operated by the state are generally known as juvenile homes. In addition there is a vast number of privately run orphanages running into thousands spread across the country. These area run by various trusts, religious groups, individual citizens, citizens groups, NGO's etc.

While some of these places endeavour to place the children for adoption a vast majority just care and educate them till they are of legal majority age and help place them back on their feet. Prominent organizations in this field include BOYS TOWN, SOS children's villages etc.

There have been scandals especially with regard to adoption. Since government rules restrict funds unless there are a certain number of residents, some orphanages make sure the resident numbers remain high at the cost of adoption.

East and Southeast Asia

Taiwan

The number of orphanages and orphans drastically dropped from 15 institutions and 2,216 persons in 1971 to 9 institutions and 638 persons by the end of 2001.

Thailand

There are still a substantial number of NGO's and informal Orphanages in Thailand, particularly in Northern Thailand near the borders of Laos and Myanmar, e.g. around Chiang Rai. Very few of the children in these establishments are orphans, most have living parents. They attract funding from well meaning tourists. Often protecting the children from trafficking/abuse is cited but the names and photographs of the children are published in marketing material to attract more funding.[89] The reality is that the safest environment for these children is almost always with their parents or in their villages with familial connections where strangers are rarely seen and immediately recognised. A very few of these orphanages, go so far as to abduct or forcibly remove children from their homes, often across the border in Myanmar. The parents in local hill tribes may be encouraged to "buy a place" in the orphanage for vast sums, being told their child will have a better future.[90] Some childrens homes claim to always try to repatriate children with their families, but the local managers & director of the homes know of no such procedures or processes.[91]

South Korea

"There are now 17,000 children in public orphanages throughout the country and untold numbers at private institutions."[92]

Cambodia

There are numerous NGOs focusing their efforts on assisting Cambodia's orphans: one group, World Orphans, constructed 47 orphanages housing over 1500 children in a three-year period.[93] The total number of orphans is much higher, but unknown: "There are no accurate figures available on how many orphans there are in Cambodia." One charity named "CHOICE Cambodia" is run by expats based in the capital city of Phnom Penh; it helps support extremely poor and homeless people and helps families stay together rather than have their children put into orphanages where they might get exploited.

China

"Currently there are 50,000 children in Chinese orphanages, while the number of abandoned children shows no sign of slowing. Official figures show that fewer than 20,000 of China's orphans are now in any form of institutional care."[94] Chinese official records fail to account for most of the country's abandoned infants and children, only a small proportion of whom are in any form of acknowledged state care.[94] The most recent figure provided seems implausibly low for a country with a total population of 1.2 billion.[94] Even if it were accurate, however, the whereabouts of the great majority of China's orphans would still be a complete mystery, leaving crucial questions about the country's child welfare system unanswered and suggesting that the real scope of the catastrophe that has befallen China's unwanted children may be far larger than the evidence in this report documents.

Laos

"It is stated that there are 20,000 orphaned children in Laos. There are only three orphanages in the whole country providing places for a total of 1,000 of these children." No Title. By Anneli Dahlbom One of the largest orphanages in Laos is in the town of Phonsavan. It is an S.O.S. orphanage and there are over 120 orphans living in the facility.[95]

Middle East and North Africa

Egypt

"The [Mosques of Charity] orphanage houses about 120 children in Giza, Menoufiya and Qalyubiya." "We [Dar Al-Iwaa] provide free education and accommodation for over 200 girls and boys." "Dar Al-Mu'assassa Al-Iwaa'iya (Shelter Association), a government association affiliated with the Ministry of Social Affairs, was established in 1992. It houses about 44 children." There are also 192 children at The Awlady, 30 at Sayeda Zeinab orphanage, and 300 at My Children Orphanage.

Note: There are about 185 orphanages in Egypt. The above information was taken from the following articles: "Other families" by Amany Abdel-Moneim. Al-Ahram Weekly (5/1999). "Ramadan brings charity to Egypt's orphans". Shanghai Star (13 December 2001). "A Child by Any Other Name" by Réhab El-Bakry. Egypt Today (11/2001).

Orphanage Project in Egypt—www.littlestlamb.org

Sudan

There is still at least one orphanage in Sudan although efforts have been made to close it[96]

Bahrain

The "Royal Charity Organization"[97] is a Bahraini governmental charity organization founded in 2001 by King Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifah to sponsor all helpless Bahraini orphans and widows. Since then almost 7,000 Bahraini families are granted monthly payments, annual school bags, and a number of university scholarships. Graduation ceremonies, various social and educational activities, and occasional contests are held each year by the organization for the benefit of orphans and widows sponsored by the organization.

Iraq

UNICEF maintains the same number at present. "While the number of state homes for orphans in the whole of Iraq was 25 in 1990 (serving 1,190 children); both the number of homes and the number of beneficiaries has declined. The quality of services has also declined."

A 1999 study by UNICEF "recommended the rebuilding of national capacity for the rehabilitation of orphans." The new project "will benefit all the 1,190 children placed in orphanages."

Palestinian Territory

"In 1999, the number of children living in orphanages witnessed a considerable drop as compared to 1998. The number dropped from 1,980 to 1,714 orphans. This is due to the policy of child re-integration in their household adopted by the Ministry of Social Affairs."

Former Soviet Union

In the post-Soviet countries, orphanages are better known as the Children Homes (Russian: Детскиe домa). After reaching school age, all children enroll into internat-schools (Russian: Школа-интернат) (see Boarding school).

Russia

Over 700,000 orphans live in Russia, increasing at the rate of 113,000 per year. UNICEF estimates that 95% of these children are social orphans, meaning that they have at least one living parent who has given them up to the state.[98][99][100][101] In 2011 Russian authorities registered 88,522 children who became orphans that year (down from 114,715 in 2009).[102]

There are few web pages for Russian orphanages in English, such as St Nicholas Orphanage[103] in Siberia or the Alapaevsk orphanage in the Urals. "Of a total of more than 600,000 children classified as being 'without parental care' (most of them live with other relatives and fosters), as many as one-third reside in institutions."[104]

In 2011, there were 1344 institutions for orphans in Russia[105] including 1094 orphanages ("Children homes")[106] and 207 special ("corrective") orphanages for children with serious health issues.[107]

Azerbaijan

"Many children are abandoned due to extreme poverty and harsh living conditions. Some may be raised by family members or neighbors but the majority live in crowded orphanages until the age of fifteen when they are sent into the community to make a living for themselves."[108]

Belarus

Approximate total – 1,773 (1993 statistics for "all types of orphanages")

Kyrgyzstan

Partial information: 85 – Ivanovka Orphanage[109]

Tajikistan

"No one can be sure how many lone children are there in the republic. About 9,000 are in internats and in orphanages."[110]

Ukraine

103,000[111]

Other information:

- thousands – Zaporozhzhya region[112]

- 150 – Kiev State Baby Orphanage[113]

- 30 – Beregena Orphanage

- 120 – Dom Invalid Orphanage[114]

Uzbekistan

Partial Information: 80 – Takhtakupar Orphanage

Oceania

Australia

Orphanages in Australia mostly closed after World War II and up to the 1970s. Children are mainly put under foster care. Notable former orphanages include the Melbourne Orphanage and the St. John's Orphanage in Goulburn, New South Wales.[115]

Indonesia

No verifiable information for the number of children actually in orphanages. The number of orphaned and abandoned children is approximately 500,000.[116]

Fiji

Orphans, children (0–17 years) orphaned due to all causes, 2005, estimate 25,000[117]

North America and Caribbean

Haiti

Haitians and expatriate childcare professionals are careful to make it clear that Haitian orphanages and children's homes are not orphanages in the North American sense, but instead shelters for vulnerable children, often housing children whose parent(s) are poor as well as those who are abandoned, neglected or abused by family guardians. Neither the number of children or the number of institutions is officially known, but Chambre de L'Enfance Necessiteusse Haitienne (CENH) indicated that it has received requests for assistance from nearly 200 orphanages from around the country for more than 200,000 children. Although not all are orphans, many are vulnerable or originate in vulnerable families that "hoped to increase their children's opportunities by sending them to orphanages." Catholic Relief Services provides assistance to 120 orphanages with 9,000 children in the Ouest, Sud, Sud-Est and Grand'Anse, but these include only orphanages that meet their criteria. They estimate receiving ten requests per week for assistance from additional orphanages and children's homes, but some of these are repeat requests."[118]

In 2007, UNICEF estimated there were 380,000 orphans in Haiti, which has a population of just over 9 million, according to the CIA World Factbook. However, since the January 2010 earthquake, the number of orphans has skyrocketed, and the living conditions for orphans have seriously deteriorated. Official numbers are hard to find due to the general state of chaos in the country.[119]

Mexico

"...at least 10,000 Mexican children live in orphanages and more live in unregistered charity homes"

- Mexican Orphanages[120]

- Mazatlan Mexico Orphanage[121]

- Casa Hogar Jeruel:[122] Orphanage in Chihuahua City, Mexico ola

United States

Traditional orphanages are no longer a part of the American adoption process.[123][124] Following World War II, most orphanages in the U.S. began closing or converting to boarding schools or group homes. Over the past few decades, orphanages in the U.S. have been replaced with smaller institutions that try to provide a group home or boarding school environment. Most children who would have been in orphanages are in these residential treatment centers (RTC), group homes, or with foster families. Adopting from RTCs, group homes, or foster families does not require working with an adoption agency, and in many areas, fostering to adopt is highly encouraged.[1][125]

Central and South America

Guatemala

"...currently there are about 20,000 children in orphanages."[126]

Peru

Casa Hoger Lamedas Pampa, in Huanaco.

Significant charities that help orphans

Prior to the establishment of state care for orphans in First World countries, private charities existed to take care of destitute orphans, over time other charities have found other ways to care for children.

- The Orphaned Starfish Foundation is a non-profit organisation based in New York City that focuses on developing vocational schools for orphans, victims of abuse and at-risk youth. It runs fifty computer centres in twenty-five countries, serving over 10,000 children worldwide Lumos works to replace institutions with community-based services that provide children with access to health, education and social care tailored to their individual needs.

- Hope and Homes for Children are working with governments to deinstitutionalise their child care systems.

- SOS Children's Villages is the world's largest non-governmental, non-denominational child welfare organization that provides loving family homes for orphaned and abandoned children.

- Dr Barnardo's Homes are now simply Barnardo's after closing their last orphanage in 1989.

- OAfrica, previously OrphanAid Africa, has been working in Ghana since 2002, to get children out of orphanages and into families, in partnership with the government and as the only private implementing partner of the National Plan of Action.[127]

- Joint Council on International Children's Services is a nonprofit child advocacy organization based in Alexandria, Virginia. It is the largest association of international adoption agencies in America, and in addition to working in 51 different countries, advocates for ethical practices in American adoption agencies

- Orphan Resources International is a non-profit that provides resources to orphanages in Guatemala Central America

- www.careforchildren.com introduced family placement to China with a pilot project in Shanghai in 1998 working with the Shanghai Government. In 2004 Care for Children partnered with the MoCA and the China Social Work Association in Beijing to develop family placement on a nationwide basis. It is now thought that a generation of children who were abandoned are living in substitute families instea of institutions in China.

- Abide Family Center (abidefamilycenter.org) is an organization working in Jinja, Uganda to reduce the number of children living in orphanages. They believe that poverty should never be a reason a child is separated from their family. For this reason the provide family preservation services including business and parenting classes, emergency/transitional housing, early childhood education and pastoral/counselling services.

- Transition Home for Orphan Boys in Afghanistan.The Transition Home was opened in 2014, and currently 6 boys live in the Transition Home. The goal of the Transition Home is that when these at risk youth leave the transition home they leave ready to live on their own. They have full-time jobs, they have furnishings for their own home, they have skills needed to live on their own, i.e. cooking, cleaning, and how to manage their finances. Prior to these youth leaving the Transition Home, the T-O-M mentors will take each youth out and help them make purchases in the markets for household items. This teaches them how to shop and what the value of a dollar is. Our mentors will then take them out to find a room/apartment to rent and help negotiate a contract and pay the upfront fees. All of this is done so that these youth now have a chance in life, they have options, and they have a choice to make something of themselves.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orphanages. |

- Adoption

- Boys Town (organization)

- Community-based care

- Cottage Homes

- Deinstitutionalisation

- Hope and Homes for Children

- Janusz Korczak

- Residential education

- Settlement movement

- Whole Child International

References

- 1 2 "Orphanage – Adoption Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia.adoption.com. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/Keeping_Children_Out_of_Harmful_Institutions_Final_20.11.09_1.pdf

- 1 2 "How to fix orphanages". The Spectator. UK. 8 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Little Princes, Conor Grennan

- ↑ "The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume XI".

- ↑ "Ashlyns School, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire". Ashlyns.herts.sch.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- ↑ Oliver, Christine and Peter Aggleton (2000). Coram's Children: Growing Up in the Care of the Foundling Hospital: 1900-1955. Coram Family. ISBN 0-9536613-1-8.

- ↑ "English Orphanages".

- ↑ America Past and Present Online-Charles Loring Brace, The Life of The Street Rats. 1872.

- 1 2 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ "Inclusion Europe | Committee of Ministers: Recommendation on Deinstitutionalization of Children with Disabilities". E-include.eu. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.unicef.org/ceecis/Planning_for_Deinstitutionalization_and_Reordering_Child_care_Services_ENG.pdf

- 1 2 "Online library: Save the Children UK". Savethechildren.org.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Online library: Save the Children UK". Savethechildren.org.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Young Children in Institutional Care at Risk of Harm". Tva.sagepub.com. 1 January 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "The Bucharest Early Intervention Project" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ Paul Lewis in Tirana (27 October 2008). "Three British evangelicals cast blame on each other in trials over child abuse at Albanian orphanage | Society". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ 7thSpace (10 August 2011). "South Africa: Homes close down for violating human rights". 7thspace.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 McKenzie, Richard B. (14 January 2010). "The Best Thing About Orphanages". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "accessed 3 September 2009". BBC News. 1 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Aid Gives Alternative to African Orphanages". nytimes.com. 2009-12-05. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- ↑ "The Case of the Vanishing Orphanage | Good Intentions Are Not Enough". Goodintents.org. 5 September 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.crin.org/docs/Family%20or%20the%20institution.doc

- ↑ "Bali's Orphanage Scam". Baliadvertiser.biz. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Nawgrahe, Prashant (15 June 2010). "Orphanage scam grows". Mid-day.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Orphanage Scams". Thirdworldorphans.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- 1 2 "News in Nepal: Fast, Full & Factual". Myrepublica.Com. 12 June 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Mydans, Seth (5 November 2001). "U.S. Interrupts Cambodian Adoptions". The New York Times. Cambodia. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "China: Adopted Children May Have Been Stolen From Their Families, Holly Williams Reports – Sky News Video Player". News.sky.com. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ Thomas Bell. "Cashing it big on children". Nepali Times. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Bell, Thomas (28 September 2011). "BBC News – Nepal comes to terms with foreign adoptions tragedy". BBC. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Bali orphanages: How tourist cash funds a racket". BBC News. 7 December 2011.

- ↑ "Albanian's Children Photo". Adoptionworx.com. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ↑ "Helping Orphans in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Soschildrensvillages.ca. 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ↑ http://www.manskligarattigheter.gov.se/dynamaster/file_archive/080325/51cacb4e4318d3f2d78c62ef72787efe/Bulgarien.pdf

- 1 2 "Tyvärr hittar vi inte sidan du söker" (PDF). Humanrights.gov.se. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ "One Heart Bulgaria – Non-profit Humanitarian Aid Organization". Oneheart-bg.org. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Tyvärr hittar vi inte sidan du söker" (PDF). Humanrights.gov.se. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ http://www.manskligarattigheter.gov.se/dynamaster/file_archive/080314/74c53f5440e23b5fa2b948c7b40eb5ca/Estland.pdf

- ↑ http://www.manskligarattigheter.gov.se/dynamaster/file_archive/080325/eec1656e32f2e28fdd08acc8fa800070/Ungern.pdf

- ↑ "Tyvärr hittar vi inte sidan du söker" (PDF). Humanrights.gov.se. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ http://www.manskligarattigheter.gov.se/dynamaster/file_archive/080314/5c08d4415225dfc8695e0f535fbfe168/Litauen.pdf

- ↑ "Tyvärr hittar vi inte sidan du söker" (PDF). Humanrights.gov.se. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ "Tyvärr hittar vi inte sidan du söker" (PDF). Humanrights.gov.se. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ "Viewpoints: Balkan boost for EU". BBC News. 2007-01-16. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ↑ "The new Romanian orphans". Childrights.ro. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- 1 2 "Hope and Homes for Children | Romania". Hopeandhomes.org. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- 1 2 3

- 1 2 "Romanian Orphans in Romania – how we help". Relieffundforromania.co.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.copii.ro/Statistici/decembrie_2004.doc

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "AFP: Romania's unwanted children given a chance". Google.com. 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- ↑ http://www.copii.ro/Files/NAPCR_brochure_200744184931.pdf

- ↑ Anastasijevic, Dejan (14 November 2007). "Disabled Serbians in Harsh Conditions". Time.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Slovakien.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ Abernethy, Virginia D. _Population Politics_. New York: Plenum Press, 1993.

- ↑ "Kelly's Directory of Herefordshire, 1913". Kelly's. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Quakers orphanage - The Orphans Press". What everyone should know about Leominster's past. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Waifs and Strays' Society". Hidden Lives Revealed. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ "Calthorpe Home For Girls, Handsworth". Hidden Lives. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Archived 13 March 2004 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "OrphanAid Africa" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ↑ http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=326123

- 1 2 "Social Protection and Risk Management – Social Safety Nets" (PDF). Worldbank.org. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Africa – Africa Region Human Development Working Paper Series" (PDF). Worldbank.org. 21 October 2004. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion – MINISTER'S VISIT TO HOPE AND HOMES FOR CHILDREN (HHC)". Migeprof.gov.rw. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Table of Contents" (PDF). Synergyaids.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Press centre – Millions of orphans in Nigeria need care and access to basic services". UNICEF. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Thokomala". Thokomala. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ http://mmorphanage.org

- ↑ http://report.kff.org/archive/aids/2000/09/kh000911.4.htm

- 1 2 3 "Unicef Togo Statistics".

- ↑ http://www.crin.org/docs/Mapping%20of%20Residential%20Care%20Institutions%20in%20Sierra%20LEone.docx

- 1 2 3 "Unicef Sierra Leona Statistics".

- 1 2 3 "Unicef Senegal Statistics".

- 1 2 "IRIN Asia | NEPAL: Protecting children from abuser-volunteers | Nepal | Children". Irinnews.org. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ http://s3.amazonaws.com/webdix/media_files/957_rdtoDeinstitutionalisation_original.pdf

- ↑ "Poverty forces Kabul parents to send kids to orphanages". csmonitor.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Haussegger, Virginia (2009). "Mahboba's promise". ABC TV 7.30 Report. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ↑ "Home | Tikkun Olam International". Tikkun Olam International. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Women And Children In Disadvantaged Situations Archived 14 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Minivan News". Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ↑ "IHF Promotional Video - youtube".

- ↑ Lambert, Chloe (11 September 2013). "Fake Orphanages - Dail Mail UK". Daily Mail. London.

- ↑ "CEO Annual Report - IHF" (PDF).

- ↑ Reitman, Valerie (1999-03-06). "S. Korea Tries to Take Care of Its Own With Domestic Adoptions - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 2013-02-02.

- ↑ "Statistics". Rykersdream.com. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Mille. Adoption. p. 75.

- ↑ "Phonsavan Orphanage". Cloud Depot Nine Charity.

- ↑ "Alternative family care technical briefing paper.pub" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ "Royal Charity Organization". Orphans.gov.bh. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ — source. "Statistics". RCWS.org. Retrieved 2013-02-02.

- ↑ "Russian Orphans Facts and Statistics". Iorphan.org. 19 May 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Information about Russian orphans". Bigfamilyministry.org. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Eke, Steven (1 June 2005). "Health warning over Russian youth". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Численность детей, оставшихся без попечения родителей, выявленных и учтенных на конец отчетного года (значение показателя за год) – Единая межведомственная информационно-статистическая система (Official Russian Statistics Site)

- ↑ Archived 7 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. 9 March 1998. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Общее число учреждений для детей-сирот и детей, оставшихся без попечения родителей – Единая межведомственная информационно-статистическая система (Official Russian Statistics Site)

- ↑ Число детских домов для детей-сирот и детей, оставшихся без попечения родителей – Единая межведомственная информационно-статистическая система (Official Russian Statistics Site)

- ↑ Число специальных (коррекционных) школ-интернатов для детей-сирот и детей, оставшихся без попечения родителей – Единая межведомственная информационно-статистическая система (Official Russian Statistics Site)

- ↑ Azerbaijan Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kyrgyzstan Children's Work Archived 23 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Photo: Vasiliy Artyushenko. "The parentless don't need cheap pity. Alla KOTLIAR, Yekaterina SHCHETKINA | Society |People". Mw.ua. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Albert Pavlov (translated from Russian by Anna Large) (21 March 2007). "A photoreport: "From Heart to Heart – 2": a trip to the rural orphanages of Zaporozhye region:: Zaporozhzhya orphans. Ukraine". Deti.zp.ua. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Kiev Children's Work Archived 18 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dnepropetrovsk Children's Work Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Swain, Sherlee. "History of Adoption and Fostering in Australia by Sherlee Swain." History of Adoption and Fostering in Australia. Oxford University, 28 Jan. 2013. Web. 05 Oct. 2013.

- ↑ "Convention on the Rights of the Child" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ↑ "Unicef Fiji Statistics".

- ↑ "Report page 14 and 15 of actual report, not web page counter" (PDF).

- ↑ Ian Birrell (4 October 2011). "Orphanages in Haiti and Cambodia rent children to fleece gullible Westerners | Mail Online". Daily Mail. UK. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "orphanagefunds.org". orphanagefunds.org. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "Laura M". Laura M. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "casahogarjeruel.org". casahogarjeruel.org. Retrieved 2013-02-02.

- ↑ "Orphanage – Adoption Information. General Info on Adopting a Child". Adoptioninformation.com. 8 November 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "Orphanages? Not Really. |". Agiftofhopeadoptions.com. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ Silverman, Jacob (18 February 2007). "HowStuffWorks "Orphanages and Foster Care"". People.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "The Children of Guatemala | BBC World Service". BBC. 28 October 2000. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.crin.org/docs/GHANA%20OVC%20NPA.pdf

External links

- The Steele home Orphanage

- The Institutions that Became Home for Britain's Children and Young People

- Remembering Children Homes and Orphanages

- Keeping Children Out of Harmful Institutions: Why we should be investing in family-based care

- Closing Orphanages – There is another way to care for the most vulnerable children

- Rescued Orphans – World's Largest Directory Of Orphanages

- MyOrphanage.org – In Touch With Orphanages

- Orphanage Review Board

-

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Orphans and Orphanages". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Orphans and Orphanages". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - World orphanages website

- Aid to Vietnamese orphans

- History of Beaver County Children's Home

- Remembering Children Homes and Orphanages