Cuban Project

| |

|

Operation Mongoose Memorandum October 4, 1962 First page of a meeting report |

The Cuban Project, also known as Operation Mongoose, was a covert operation of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) developed during the first year of President John F. Kennedy's administration. On November 30, 1961, aggressive covert operations against Fidel Castro's government in Cuba were authorized by President Kennedy. The operation was led by United States Air Force General Edward Lansdale and went into effect after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Operation Mongoose was a secret program against Cuba aimed at removing the Communists from power, which was a prime focus of the Kennedy administration according to Harvard historian Jorge Domínguez.[1] A document from the United States Department of State confirms that the project aimed to "help Cuba overthrow the Communist regime", including its leader Fidel Castro, and it aimed "for a revolt which can take place in Cuba by October 1962". US policymakers also wanted to see "a new government with which the United States can live in peace".[2]

Origins

After the Cuban Revolution, and communism's rise under Fidel Castro, the U.S. government was determined to undercut the socialist revolution's integrity and install in its place a government more in line with U.S. philosophy. A special committee was formed to search for ways to overthrow Castro when the Bay of Pigs Invasion failed. The committee became part of the Kennedy imperative to keep a tough line on communism, especially inasmuch as Cuba was the nearest communist state to the U.S.

It was based on the U.S. government's estimation that coercion inside Cuba was severe and that the regime was serving as a spearhead for allied communist movements elsewhere in the Americas.[3] Following the failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, Robert Kennedy and Richard Goodwin suggested to President Kennedy that the U.S. government begin a sustained campaign of intelligence and covert action against the communist regime in Cuba.[4] They believed in a centralized effort led by senior officials from the White House and other government agencies to remove Fidel Castro and overthrow the Cuban regime. Following a meeting in the White House on November 3, 1961, this initiative became known as Operation Mongoose and would be led by Air Force Brigadier General Edward Lansdale.[4]

Other agencies were brought in to assist with the planning and execution of Operation Mongoose. Representatives from the State Department, the Defense Department, and the CIA were assigned larger roles in implementing the operation's activities, while representatives from the US Information Agency and the Department of Justice were also called on occasionally to assist with the operation.[4] As the operation's leader, Brigadier General Lansdale received briefings and updates from these agencies and reported directly to a group of high-ranking government officials, known as Special Group-Augmented (SG-A).

Some of the outlined goals of the operations included intelligence collection and the generation of a nucleus for a popular Cuban movement, along with exploiting the potential of the underworld in Cuban cities and enlist the cooperation of the Church to bring in women in Cuba into actions to undermine the Communist control system.[4] The Departments of State, Defense, and Justice were responsible for a combination of these objectives. Kennedy and the rest of SG-A hoped to depose the Castro regime and bring change to Cuba's political system.

President Kennedy, the Attorney General, CIA Director John McCone, Richard Goodwin, and Brigadier General Lansdale met on November 21, 1961 to discuss plans for Operation Mongoose. Robert Kennedy stressed the importance of immediate dynamic action to discredit the Castro regime in Cuba.[4] He remained disappointed from the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion just a couple months prior. By the end of November, President Kennedy had finalized details for Operation Mongoose. Lansdale remained in charge of the operation, and access to knowledge of Operation Mongoose remained strictly confidential and limited. As was common throughout the Kennedy presidency, decision making would be centralized and be housed within the secret Special Group.[4] At this time, Operation Mongoose was underway.

Planning

The U.S. Defense Department's Joint Chiefs of Staff saw the project's ultimate objective to be to provide adequate justification for U.S. military intervention in Cuba. They requested that the Secretary of Defense assign them responsibility for the project, but Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy retained effective control.

Mongoose was led by Edward Lansdale at the Defense Department and William King Harvey at the CIA. Lansdale was chosen due to his experience with counter-insurgency in the Philippines during the Hukbalahap Rebellion, and also due to his experience supporting Vietnam's Diem regime. Samuel Halpern, a CIA co-organizer, conveyed the breadth of involvement: "CIA and the US Army and military forces and Department of Commerce, and Immigration, Treasury, God knows who else – everybody was in Mongoose. It was a government-wide operation run out of Bobby Kennedy's office with Ed Lansdale as the mastermind."[5]

There were 33 tasks[6] or plans[7] (as there are 33[8] living species of mongooses) considered under the Cuban Project, some of which were carried out. The plans varied in efficacy and intention, from propagandistic purposes to effective disruption of the Cuban government and economy. Plans included the use of U.S. Army Special Forces, destruction of Cuban sugar crops, and mining of harbors.

Operation Northwoods was a 1962 plan, which was signed by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and presented to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara for approval, that intended to use false flag operations to justify intervention in Cuba. Among things considered were real and simulated attacks which would be blamed on the Cuban government. These would have involved attacking, or reporting fake attacks on Cuban exiles, U.S. military targets, Cuban civilian aircraft, and development of a false-flag terror campaign on U.S. soil. The operation was rejected by Kennedy and never carried out.

The Cuban Project played a significant role in the events leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The Project's six-phase schedule was presented by Edward Lansdale on February 20, 1962; it was overseen by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. President Kennedy was briefed on the operation's guidelines on March 16, 1962. Lansdale outlined the coordinated program of political, psychological, military, sabotage, and intelligence operations as well as assassination attempts on key political leaders. Each month since his presentation, a different method was in place to destabilize the communist regime, including the publication of Anti-Castro views, armaments for militant opposition groups, the establishment of guerilla bases throughout the country and preparations for an October military intervention in Cuba. Many individual plans were devised by the CIA to assassinate Castro. Plans to discredit Castro in the eyes of the Cuban public included contaminating his clothing with thallium salts that would make his trademark beard fall out and spraying a broadcasting studio with hallucinogens before a televised speech. Assassination plots included poisoning a box of Castro's favorite cigars with botulinus toxin and placing explosive seashells in his favorite diving spots.[9]

Execution

The CIA operation was based in Miami, Florida and among its other aspects enlisted the aid of the Mafia (who were eager to regain their Cuban casino operations) to plot an assassination attempt against Castro; William Harvey was one of the CIA case officers who directly dealt with mafioso John Roselli.[10]

.pdf.jpg)

Professor of History Stephen Rabe writes that "scholars have understandably focused on…the Bay of Pigs invasion, the US campaign of terrorism and sabotage known as Operation Mongoose, the assassination plots against Fidel Castro, and, of course, the Cuban Missile Crisis. Less attention has been given to the state of US-Cuban relations in the aftermath of the missile crisis." Rabe writes that reports from the Church Committee reveal that from June 1963 onward, the Kennedy administration intensified its war against Cuba while the CIA integrated propaganda, "economic denial", and sabotage to attack the Cuban state as well as specific targets within.[11] One example cited is an incident where CIA agents, seeking to assassinate Castro, provided a Cuban official, Rolando Cubela Secades, with a ballpoint pen rigged with a poisonous hypodermic needle.[11] At this time, the CIA received authorization for 13 major operations in Cuba, including attacks on an electric power plant, an oil refinery, and a sugar mill.[11] Rabe has argued that the "Kennedy administration... showed no interest in Castro's repeated request that the United States cease its campaign of sabotage and terrorism against Cuba. Kennedy did not pursue a dual-track policy toward Cuba.... The United States would entertain only proposals of surrender." Rabe further documents how "Exile groups, such as Alpha 66 and the Second Front of Escambray, staged hit-and-run raids on the island... on ships transporting goods…purchased arms in the United States and launched...attacks from the Bahamas."[11]

Harvard Historian Jorge Domínguez states that Mongoose's scope included sabotage actions against a railway bridge, petroleum storage facilities, a molasses storage container, a petroleum refinery, a power plant, a sawmill, and a floating crane. Domínguez states that "only once in [the] thousand pages of documentation did a US official raise something that resembled a faint moral objection to US government sponsored terrorism."[1] Actions were subsequently carried out against a petroleum refinery, a power plant, a sawmill, and a floating crane in a Cuban harbour.

The Cuban Project was originally designed to culminate in October 1962 with an "open revolt and overthrow of the Communist regime." This was at the peak of the Cuban Missile Crisis, where the U.S. and the USSR came alarmingly close to nuclear war over the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba, verified by low flying aircraft on photographic missions and ground surveillance photography. The operation was suspended on October 30, 1962, but 3 of 10 six-man sabotage teams had already been deployed to Cuba.

Dominguez writes that Kennedy put a hold on Mongoose actions as the Cuban Missile Crisis escalated, but "returned to its policy of sponsoring terrorism against Cuba as the confrontation with the Soviet Union lessened."[1] However, Noam Chomsky has argued that "terrorist operations continued through the tensest moments of the missile crisis", remarking that "they were formally canceled on October 30, several days after the Kennedy and Khrushchev agreement, but went on nonetheless". Accordingly, "the Executive Committee of the National Security Council recommended various courses of action, "including ‘using selected Cuban exiles to sabotage key Cuban installations in such a manner that the action could plausibly be attributed to Cubans in Cuba’ as well as ‘sabotaging Cuban cargo and shipping, and [Soviet] Bloc cargo and shipping to Cuba."[12]

Operation Mongoose consisted of a program of covert action, including sabotage, psychological warfare, intelligence collection, and the creation of an internal revolution against the communist government.[4] From the outset, Lansdale and fellow members of the SG-A identified internal support for an anti-Castro movement to be the most important aspect of the operation. American organization and support for anti-Castro forces in Cuba was seen as key, which expanded American involvement from what had mostly been economic and military assistance of rebel forces. Therefore, Lansdale hoped to organize an effort within the operation, led by the CIA, to covertly build support for a popular movement within Cuba. This was a major challenge. It was difficult to identify anti-Castro forces within Cuba and there lacked a groundswell of popular support that Cuban insurgents could tap into.[4] Within the first few months, an internal review of Operation Mongoose cited the CIA's limited capabilities to gather hard intelligence and conduct covert operations in Cuba. By January 1962, the CIA had failed to recruit suitable Cuban operatives that could infiltrate the Castro regime.[4] The CIA and Lansdale estimated that they required 30 Cuban operatives. Lansdale criticized the CIA effort to ramp up their activities to meet Operation Mongoose's expedient timelines. Robert McCone of the CIA complained that Lansdale's timeline was too accelerated and that it would be difficult to achieve the tasks demanded in such a short timeframe.

In February, Lansdale offered a comprehensive review of all Operation Mongoose activities to date. His tone was urgent, stating that "time is running against us. The Cuban people feel helpless and are losing hope fast. They need symbols of inside resistance and of outside interest soon. They need something they can join with the hope of starting to work surely towards overthrowing the regime."[4] He asked for a ramp up of efforts from all agencies and departments to expedite the execution of the Cuban Project. He laid out a six-part plan targeting the overthrow of the Castro government in October 1962.

In March 1962, a key intelligence report, written by the CIA, was produced for Lansdale. It showed that although roughly only a quarter of the Cuban population stood behind the Castro regime, the rest of the population was both disaffected and passive. The report writes that the passive majority of Cubans had "resigned to acceptance of the present regime as the effect government in being".[4] The conclusion was that an internal revolt within Cuba was unlikely.

The lack of progress and promise of success through the first couple of months of the operation strained relationships within the SG-A. McCone criticized the handling of the operation, believing that "national policy was too cautious" and suggested a US military effort to train more guerrillas, and large-scale amphibious landing military exercises were conducted off the coast of North Carolina in April, 1962.[4]

By July, the operation still showed little progress. Phase I of Operation Mongoose drew to a close. In his July review, Lansdale recommended a more aggressive plan of action in the near future. He believed that time was of the essence, especially with the intensified Soviet military build-up in Cuba at the time. New plans to recruit more Cubans to infiltrate the Castro regime, interrupt Cuban radio and television broadcasts, and the deployment of commando sabotage units were drawn up.[4]

However, by late August, the Soviet military build-up in Cuba disgruntled the Kennedy administration. The fear of open military retaliation against the United States and Berlin for the US covert operations in Cuba slowed down the operation. By October, as the Cuban Missile Crisis heated up, President Kennedy demanded the cessation of Operation Mongoose. Operation Mongoose formally ceased its activities at the end of 1962.[4]

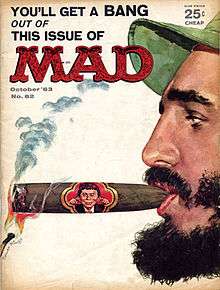

Assassination proposals

Many assassination ideas were floated by the CIA during Operation Mongoose.[13] The most infamous was the CIA's alleged plot to capitalize on Castro's well-known love of cigars by slipping into his supply a very real and lethal "exploding cigar."[14][15][16][17][18] While numerous sources state the exploding cigar plot as fact, at least one source asserts it to be simply a myth,[19] and another, mere supermarket tabloid fodder.[20] Another suggests that the story does have its origins in the CIA, but that it was never seriously proposed by them as a plot. Rather, the plot was made up by the CIA as an intentionally "silly" idea to feed to those questioning them about their plans for Castro, in order to deflect scrutiny from more serious areas of inquiry.[21]

Other plots to assassinate Castro that are ascribed to the CIA include, among others: poisoning his cigars[22] (a box of the lethal smokes was actually prepared and delivered to Havana[23]); exploding seashells to be planted at a scuba diving site;[24] a gift diving wetsuit impregnated with noxious bacteria[24] and mold spores,[25] or with lethal chemical agents; infecting Castro's scuba regulator apparatus with tuberculous bacilli; dousing his handkerchiefs, his tea, and his coffee with other lethal bacteria;[26] having a former lover slip him poison pills;[24][26] and exposing him to various other poisoned items such as a fountain pen and even ice cream.[13] The CIA even tried to embarrass Castro by attempting to sneak thallium salts, a potent depilatory, into Castro's shoes, causing "his beard, eyebrows, and pubic hair to fall out".[27] The US Senate's Church Committee of 1975 stated that it had confirmed at least eight separate CIA run plots to assassinate Castro.[28] Fabian Escalante, who was long tasked with protecting the life of Castro, contends that there have been 638 separate CIA assassination schemes or attempts on Castro's life.[26]

Concerning the aforementioned fountain pen, this was said to be loaded with the poison Black Leaf 40 and passed to a Cuban asset in Paris the day of President Kennedy's assassination, November 22nd, 1963. Notably, the evidence also indicates that these two events occurred simultaneously, in the same moment. [29][30] Rolando Cubela, the potential assassin, contests this account, saying Black Leaf 40 was not in the pen. U.S. Intelligence later responded to say that Black Leaf 40 was merely a suggestion but Cubela thought that there were other poisons that would be much more effective. Overall he was unimpressed with the device. [31] The inventor understood that Cubelo rejected the device altogether. [32]

In March 1960 author Ian Fleming met John F. Kennedy at a dinner through a mutual friend where he proposed several schemes to discredit Castro.[33][34]

In March 1961, CIA officer Richard M. Bissel had contacted a member of the mafia to assassinate Castro. Bissel tapped Tony Varona to carry out the assassination. Varona was given thousands of dollars and poison pills. Varona had managed to hand off a vial of poison to a restaurant worker in Havana, who was to slip it into Castro's ice cream cone. Cuban Intelligence officers later found the vial frozen to the coils in a freezer.[35]

Legacy

The Cuban Project, as with the earlier Bay of Pigs invasion, is widely acknowledged as an American policy failure against Cuba. According to Noam Chomsky, it had a budget of $50 million per year, employing 2,500 people including about 500 Americans, and still remained secret for 14 years, from 1961 to 1975. It was revealed in part by the Church Commission in the U.S. Senate and in part "by good investigative journalism." He said that "it is possible that the operation is still ongoing [1989], but it certainly lasted throughout all the 70's."[36]

Media portrayals

In the Oliver Stone film JFK, Operation Mongoose is portrayed in flash-back sequences as a training ground where, among others, Lee Harvey Oswald becomes versed in anti-Castro militia tactics.

See also

- 638 Ways to Kill Castro

- Assassination attempts on Fidel Castro

- Church Committee

- Cuba–United States relations

- NSC 5412/2 Special Group

- Operation 40

- Operation Northwoods

- Technical Services Staff

References

- 1 2 3 Domínguez, Jorge I. "The @#$%& Missile Crisis (Or, What was 'Cuban' about US Decisions during the Cuban Missile Crisis.Diplomatic History: The Journal of the Society for Historians of Foreign Relations, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Spring 2000): 305–15.)

- ↑ US Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States 1961–1963, Volume X Cuba, 1961–1962 Washington, DC )

- ↑ Michael Grow. "Cuba, 1961". U.S. Presidents and Latin American Interventions: Pursuing Regime Change in the Cold War. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2008. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Husain, Aiyaz (February 2005). "Covert Action and US Cold War Strategy in Cuba, 1961-62". Cold War History.

- ↑ James G. Blight, and Peter Kornbluh, eds., Politics of Illusion: The Bay of Pigs Invasion Reexamined. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1999, 125)

- ↑ https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v10/d291

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1997/11/23/weekinreview/stupid-dirty-tricks-the-trouble-with-assassinations.html

- ↑ Vaughan, Terry A.; James M. Ryan; Nicholas J. Czaplewski (2010). Mammalogy. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 300. ISBN 0-7637-6299-7

- ↑ "Castro: Profile of the great survivor". BBC News. 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ Jack Anderson (1971-01-18). "6 Attempts to Kill Castro Laid to CIA". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 3 4 Stephen G. Rabe -Presidential Studies Quarterly. Volume: 30. Issue: 4. 2000,714

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam. Hegemony or Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance, Henry Holt and Company, 80.

- 1 2 Stewart Brewer and Michael LaRosa (2006). Borders and Bridges: A History of US-Latin American Relations. Westport, Ct.: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 123. ISBN 0-275-98204-1.

- ↑ Malcolm Chandler and John Wright (2001). Modern World History. Oxford: Heinemann Education Publishers. p. 282. ISBN 0-435-31141-7.

- ↑ Joseph J. Hobbs, Christopher L. Salter (2006). Essentials Of World Regional Geography (5th ed.). Toronto: Thomson Brooks/Cole. p. 543. ISBN 0-534-46600-1.

- ↑ Derek Leebaert (2006). The Fifty-year Wound: How America's Cold War Victory Shapes Our World. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 302. ISBN 0-316-51847-6.

- ↑ Fred Inglis (2002). The People's Witness: The Journalist in Modern Politics. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 223. ISBN 0-300-09327-6.

- ↑ BBC News (2008-02-19). "Castro: Profile of the great survivor". Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ↑ David Hambling (2005). Weapons Grade: How Modern Warfare Gave Birth to Our High-Tech World. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 391. ISBN 0-7867-1769-6.

- ↑ Charles R. Morris (1984). A Time of Passion: America, 1960–1980. New York: Harper & Row. p. 210. ISBN 0-06-039023-9.

- ↑ Lamar Waldron and Thom Hartmann (2005). Ultimate Sacrifice: John and Robert Kennedy, the Plan for a Coup in Cuba, and the Murder of JFK. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 409. ISBN 0-7867-1832-3.

- ↑ Lucien S. Vandenbroucke (1993). Perilous Options: Special Operations as an Instrument of US Foreign Policy. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-19-504591-2.

- ↑ Charles Schudson (1992). Watergate in American Memory: How We Remember, Forget, and Reconstruct the Past. New York: Basic Books. p. 45. ISBN 0-465-09084-2.

- 1 2 3 Ted Shackley and Richard A. Finney (1992). Spymaster: my life in the CIA. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, Inc. p. 57. ISBN 1-57488-915-X.

- ↑ Fidel Castro and Ignacio Ramonet (2008). Fidel Castro: My Life: a Spoken Autobiography. Washington D.C.: Simon and Schuster. p. 262. ISBN 1-4165-5328-2.

- 1 2 3 Campbell, Duncan (April 3, 2006). "638 ways to kill Castro". London: The Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2006-05-28.

- ↑ "If at First You Don't Succeed: Killing Castro". historyhouse.com. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ↑ Gus Russo (1998). Live by the Sword: The Secret War Against Castro and the Death of JFK. Baltimore: Bancroft Press. p. 83. ISBN 1-890862-01-0.

- ↑ REPORT ON PLOTS TO ASSASSINATE FIDEL CASTRO (1967 INSPECTOR GENERAL'S REPORT)pg. 14 web

- ↑ REPORT ON PLOTS TO ASSASSINATE FIDEL CASTRO (1967 INSPECTOR GENERAL'S REPORT) pg. 15 web

- ↑ REPORT ON PLOTS TO ASSASSINATE FIDEL CASTRO (1967 INSPECTOR GENERAL'S REPORT) pg. 104 web

- ↑ REPORT ON PLOTS TO ASSASSINATE FIDEL CASTRO (1967 INSPECTOR GENERAL'S REPORT) pg. 103 web

- ↑ p.323 Pearson, John The Life of Ian Fleming Cape, 1966

- ↑ p.178 Comentale, Edward P.; Watt, Stephen & Willman, Skip Ian Fleming & James Bond: The Cultural Politics of 007. Indiana University Press, 2005

- ↑ Weiner, Tim (2007). A Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. New York: Doubleday. pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Noam Chomsky, Peter Mitchell, Understanding Power, 2002, The New Press

External links

- Operation Mongoose: The Cuba Project, Cuban History Archive, 20 Feb 1962.

- The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, The National Security Archive.

- Meeting with the Attorney General of the United States Concerning Cuba, CIA minutes, 19 January 1962.

- Justification for US Military Intervention in Cuba, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 13 March 1962.

- Minutes of Meeting of the Special Group on Operation Mongoose, 4 October 1962.

- CIA Inspector General's Report on Plots to Assassinate Fidel Castro, CIA Historical Review Program, 23 May 1967. (HTML version)