North Cascades National Park

| North Cascades National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category Ib (wilderness area) | |

|

View from Sahale Arm | |

| |

| Location | Whatcom, Skagit, and Chelan counties, Washington, USA |

| Nearest city | Mount Vernon, Washington |

| Coordinates | 48°49′58″N 121°20′51″W / 48.83278°N 121.34750°WCoordinates: 48°49′58″N 121°20′51″W / 48.83278°N 121.34750°W[1] |

| Area | 504,781 acres (204,278 ha)[2] |

| Established | October 2, 1968 |

| Visitors | 21,623 (in 2013)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | North Cascades National Park |

North Cascades National Park is a U.S. National Park located in the state of Washington. The park is the largest of the three National Park Service units that comprise the North Cascades National Park Service Complex. Several national wilderness areas and British Columbia parkland adjoin the National Park. The park features rugged mountain peaks and protects portions of the North Cascades range.

Human history

Paleoindians and native Americans

Human history in the region now part of North Cascades National Park dates back to the end of the last glacial period, and the region has been continuously inhabited for at least the last 8-10,000 years.[4] At that time, Native American ancestors of Skagit tribes slowly advanced from Puget Sound into the interior mountainous region as the glacial ice retreated. Archeological evidence of continuous human presence in the North Cascades dates to 4,470 B.P. and rocks procured from sources in the region were used to manufacture stone tools and weapons for several millennia.[4] Hozomeen chert, a type of rock well-suited to the fabrication of implements, was mined from near Hozomeen Mountain, just east of the park border, for the last 8,400 years. Hozomeen chert is part of the archeological record throughout the Skagit River Valley, west of the park and in regions to the east, indicating people visited the region if for no other purpose than to obtain raw materials.[5][6] Prehistoric micro blades dating back to 9,600 years before present have been discovered at Cascade Pass, a mountain pass that connects the western lowlands to the interior regions of the park and the Stehekin River Valley. The micro blades are part of an archeological assemblage that includes five distinct cultural periods, indicating that people were traveling into the mountains nearly 10,000 years ago.[7] The archeological excavation at Cascade Pass is one of the 260 prehistoric sites that have been identified in the park.[8]

When white explorers first entered the area in the late 18th century, perhaps 1,000 Skagits lived there.[9] The Skagits lived in settlements, culling their needs from the waterways and traveling by way of canoe. Skagits formed a loose confederation of tribes that united if threatened by outside tribes such as the Haidas, who lived to the north.[9] They erected large houses or lodges that might house multiple families, each with their own partitioned area and entrance. The lodges were 100 feet (30 m) in length and 20 to 40 ft (6.1 to 12.2 m) in width and the roofs were shed-styles, with a single-pitch; structures built by other Puget Sound tribes usually had gable roofs with more than one-pitch.[9] The Skagits were generally lowlanders, who only ventured into the North Cascades during the summer months, and structures in the mountains were more modest, consisting mostly of temporary buildings erected with poles and covered with branches.[9] The Skagits erected totem poles and participated in potlatch ceremonies, similar to the Haidas, but with less complexity and extravagance. By 1910, only about 56 Skagits remained in the region, but their numbers have since rebounded some.[9]

Inland and residing to the north and east of the Skagits, the Nlaka'pamux (or Thompson Indians and named after explorer David Thompson), Chelan, Okanogan and Wenatchi tribes lived partly or year-round in the eastern sections of the North Cascades.[9] The Skagits and Thompsons often had disputes, and raided each other's camps in search of slaves or to exact retributions. Like the coastal based Skagits, inland tribes also constructed long lodges which were occupied by numerous families, though the style of construction was slightly different as the lodges did not have partitions separating one family from another, and were frame constructed and covered with reed mats rather than from cedar planking.[9] One Wenatchi lodge was described by Thompson as being 240 ft (73 m) long.[9] Inland tribes were more likely to travel on foot or horseback than by canoe since the inland regions were less densely forested. Inland tribes also had less bountiful fisheries and greater weather extremes due to being further away from the moderating influence of the Pacific Ocean. Additionally, inland tribes rarely erected totem poles or participated in potlatch ceremonies. By the beginning of the 20th century, inland tribes, like their coastal neighbors, had much reduced populations from when they had first encountered white explorers a hundred years earlier, mostly due to smallpox and other diseases.[9]

Modern exploration

The earliest white explorer to enter the North Cascades was most likely a Scotsman named Alexander Ross in 1811, who was in the employ of the Pacific Fur Company, an American-owned company. To the southeast of the modern park boundary, Ross and other members of the company constructed Fort Okanogan in 1811, as a base to operate from during the early period of the Pacific Northwest fur trade.[10] Fort Okanogon was the first American settlement in present-day Washington, and well north of the route followed by members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806, and also north of Fort Vancouver which was on the Columbia River.[11] Fort Okanogon was later owned by the North West Company and then the Hudson's Bay Company, both of which were British-owned.[11] Much of the trade in furs was conducted between Native American and a few white trappers at trading posts staffed by representatives of the fur trading company. In one season alone, Ross traded for 1500 beaver pelts.[10] In 1814, Ross became the first known white explorer to cross the major peaks of the North Cascades, but he was less interested in exploration than in simply attempting to discover a route which would easily connect the fur posts of interior Washington with Puget Sound to the west.[10][11] Ross was accompanied by three Indians, one of which was a guide, who led the party to a high pass in the North Cascades. Ross and the guide may have travelled as far west as the Skagit River, but failed to get to Puget Sound.[11] Fur trading slowed considerably as demand for furs decreased in the 1840s but a few residents continued to at least augment their income by trapping for furs in the future park until 1968 when the park was established, rendering the activity illegal.[10] Aside from isolated trappers, the North Cascades saw no explorations until the 1850s. In 1853, U.S. Army Captain George B. McClellan led a party that explored for potential places that a railroad could be built through the region; McClellan determined that the mountains were too numerous and precipitous and that any railway would have to be constructed well south of the current park.[12]

American and British disputes in the region centered on the fur trade and the Treaty of 1818 allowed for joint administration of Oregon Country, as it was referred to in the U.S. - the British Empire referred to the region as the Columbia District.[13] The treaty set the international boundary at the 49th parallel, but this was not as clear west of the Rocky Mountains, since the rival fur trading outfits had their own ideas about where the boundary should be. The Oregon boundary dispute between Britain and the U.S. eventually led to the Oregon Treaty of 1846, and the 49th parallel forms both the current international boundary as well as the northern border of the current park.[13] During the late 1850s, members of the U.S. North West Boundary Commission explored the boundary region, attempting to identify which mountains, rivers and lakes belonged to which country.[13] One party of the commission was led by explorer Henry Custer, and they explored much of the northern district of the park, publishing their report in the 1860s. Custer's party crossed Whatcom Pass in 1858 and were the first whites to see Challenger Glacier and Hozomeen Mountain.[13] So impressed with the scenic grandeur of the region, Custer succinctly stated, "must be seen, it cannot be described".[14] During the explorations by Custer, gold was discovered in a quartz vein on the slopes of Eldorado Peak.[15]

In 1882, U.S. Army Lt. Henry Hubbard Pierce led a government sponsored exploration that traversed along the western boundary of the southern section of the current park, in search of transportation routes and natural resources. As had been true for the party led by McClellan in the 1850s, Pierce failed to find a suitable route for a railway, and only marginally suitable routes for roads. Further expeditions by the military in 1883 and 1887 also determined that the mountains were virtually impenetrable.[12] Explorers continued to seek out routes for wagon roads and railways and by the end of the 19th century much of the park had been explored, but it wasn't until 1972 that the North Cascades Highway finally bisected the mountains.[12]

Mining, logging and dam construction

Prospectors had entered the North Cascades by the 1850s; placer mining first started along the banks of the Skagit River. In the 1870s, placer mining also commenced along Ruby Creek and hundreds of miners flocked to the region even though it was difficult to access. Most mining activity along Ruby Creek had ended by the 1880s but was soon replaced by hard rock mining for silver and other minerals.[10] This second period of mining lasted from the 1890s to the 1940s, but was only marginally more lucrative.[16] Miners were hampered by short working seasons, difficult terrain, low quantities of ore and a lack of financial investments.[17] Miners built many of the first trails and roads into portions of the backcountry, some that involved intricate engineering, including bridges over the numerous streams and dynamiting rock ledges above steep gorges during trail construction.[10][18] One mining company built a series of flumes, the longest of which was over 3 miles (4.8 km), to both transport lumber and to supply water for use in their hydraulic mining operation.[10] During the latter years of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, larger scale mining companies mined silver and lead in addition to gold, mostly for little to no profitability. The demand for various metals was not constant, so prices tended to fluctuate too much for mining to be viable.[10] Once the region became a national park, some privately owned mining inholdings remained. One such inholding, the Thunder Creek mine, was still privately owned as of 1997.[19]

Unlike many other regions of the Pacific Northwest, logging had little major impact on the future park.[20] The ruggedness of the terrain and the existence of more economically viable timber resources which were closer to transportation routes, largely dissuaded the timber industry from logging in the area. In 1897 the Washington Forest Reserve was set aside, essentially preserving the forestland that would later become the park. By 1905, the management of the reserve was transferred from the U.S. Department of the Interior to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Forest Service was subsequently created to administer these forest reserves nationwide, which were redesignated as National Forests.[10] Though the Department of Agriculture allowed commercial enterprises the right to log the forest with a permit, most of the timber taken from the region was used only locally for the construction of cabins and similar small scale enterprises. Logging expanded when the Skagit River Hydroelectric Project was commenced by the public utility Seattle City Light in the 1920s.[18] Almost 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) of timber would have been left underwater by the completion of the Ross Dam. A contract to extract the timber was awarded in 1945 and the project was not completed until 1958.[10] None of the dams or areas that were extensively logged are within the current boundaries of the national park, but they are in the adjoining Ross Lake National Recreation Area.

Establishing the national park

The establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 and Yosemite National Park in 1890, led preservationists to argue for similar protections for other areas in the U.S. Even before the North Cascade region was provided some protection when it was designated a Forest Reserve in 1897, activists argued that the region should be afforded the greater protection accorded from a National Park designation.[21] A petition was submitted in 1892 by Washington state citizens to establish a national park to the north of Lake Chelan, as many who had visited the region believed it to have scenery, "greater than Switzerland's".[22] Further efforts surfaced in 1906 and again in the years between 1916 and 1921, when several bills to designate the region a national park failed to get ratification from the U.S. Congress.[22] Not all locals supported the idea of a national park, as they felt that such a designation would negatively impact their economic situation. The U.S. Forest service was also not in favor of a park as that would mean they would have to relinquish control over the land, an event that was not uncommon since many parks that were being established were originally managed by the Forest Service. In an effort to appease their detractors, the U.S. Forest Service designated Primitive Areas which would provide increased protections to some of the most pristine regions they managed.[22] By the mid-1930s, forester Bob Marshall argued that the region should be set aside as wilderness, as that would keep the National Park Service out since their mandate would force them to construct roads and build "improvements" for the sake of tourism. Rival interests continued to argue over whether the lands should remain under the management of the U.S. Forest Service or the National Park Service but by the 1960s, the environmentalist argument advocating for a national park prevailed.[22] Though the North Cascades National Park Act designated the region as a National Park on October 2, 1968, the National Park Service did not commence direct management until January 1, 1969.[23] The North Cascades National Park Act also designated Ross Lake and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas. Redwood National Park in California was also signed into existence on the same day as the North Cascades.[22] By 1988, much of Bob Marshall's original plan to set aside the future park as wilderness was achieved when 93 percent of North Cascades National Park was designated as the Stephen Mather Wilderness.[24]

Park management

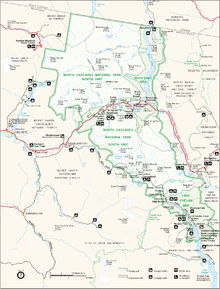

North Cascades National Park is managed by the National Park Service and the park headquarters is in Sedro-Woolley, Washington. The park consists of a northern and a southern district or unit. These are separated by Ross Lake National Recreation Area. The southeast boundary of the southern district abuts Lake Chelan National Recreation Area; the park and two recreation areas are managed as the North Cascades National Park Complex.[25] The three entities were all established in 1968 and in 1988, much of the park complex was designated wilderness as the Stephen Mather Wilderness, preventing further non-natural alterations to 93 percent of the park.[24][26] The mandate of the National Park Service is to "... preserve and protect natural and cultural resources". The Organic Act of August 25, 1916, established the National Park Service as a federal agency. One major section of the Act has often been summarized as the "Mission", "... to promote and regulate the use of the ... national parks ... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."[27] In keeping with this mandate, hunting is illegal in the park, as is mining, logging and removal of natural or cultural resources. Additionally, oil and gas exploration and extraction are not permitted.

In 2013, North Cascades National Park recorded over 21,000 visitors, but adjoining Ross Lake National Recreation Area reported over 725,000 visitors and Lake Chelan National Recreation Area had just under 40,000 visitors.[3] Peak visitation is between the months of June and September.[26] The vast majority of visitors come to Ross Lake National Recreation Area which is easily accessible on Washington State Route 20, also known as the North Cascades Highway, and the only road which bisects the park complex. North Cascades National Park Complex had an operating base budget of $7,700,000 for fiscal year 2010, augmented by another $3,700,000 of non-base funding which can fluctuate significantly from year to year, and additional funding from revenue generated from concessionaire contracts and user fees. Much of the budget is for staffing, with 83 percent directed to pay for the employ of 81 permanent employees, not all of which are employed year-round, and the nearly 250 seasonal and term employees that work primarily in the summer months.[26]

The North Cascades National Park Complex management activities include facilities management, which oversees the maintenance and construction of roads, 396 miles (637 km) of trails and 260 buildings, and resource management, which is involved in areas as diverse as fire management, biological resource management and glacier monitoring. Park employees also provide law enforcement, search and rescue, medical response, interpretive services and educational outreach, and the administrative division which oversees budgets, personnel and contracting services.[26]

Geography

North Cascades National Park is located in portions of Whatcom, Skagit, and Chelan counties in the U.S. state of Washington. Bisected by Ross Lake National Recreation Area, the park consists of two districts; the northern and southern. The northern boundary of the north district is also the international border between the U.S. and Canada; the latter manages adjoining Skagit Valley Provincial Park. The entire eastern and southern boundary of the north district is bordered by Ross Lake NRA. The western side of the north district is bordered by Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest within which lies the Mount Baker and Noisy-Diobsud Wildernesses, both of which border the park.[28][29][30] Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest also borders a portion of the southern district of North Cascades National Park, to the southwest. Also along the southwest border lies Wenatchee National Forest, within which lies the Glacier Peak Wilderness.[28][31] The southern boundary of the park is shared with Lake Chelan NRA, while a small section of the eastern boundary is shared with Okanogan National Forest.[28] The Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness lies in Wenatchee and Okanogan National Forests along the southeastern park boundary.[32] North Cascades National Park has nearly 9,000 feet (2,700 m) of vertical relief, with a park high point atop Goode Mountain and the western valleys situated at only around 400 ft (120 m) above mean sea level, the park has a highly varied ecosystem, including eight life zones.[33][34] Erosion from water and glacial ice have made the mountain peaks of the North Cascades some of the steepest mountain ranges in the contiguous U.S., rising between 4,000 and 6,000 ft (1,200 and 1,800 m) above their bases.[35] North Cascades National Park is home to over 300 glaciers as well as 300 lakes and is the headwaters for the Skagit, Stehekin and Nooksack Rivers.[34][36] The ruggedness of the terrain has been an obstacle to urbanization and consequently, North Cascades National Park is almost entirely wilderness though it is but 120 miles (190 km) from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport in Seattle, Washington.[37]

North Cascades geology

Named after the mountain peaks that are the central feature of the region, the North Cascades are a subsection of the Cascade Range which extends from northern California to British Columbia, Canada. The North Cascades are the northern section of the Cascade Range and unlike their southern counterparts, which consist mostly of Tertiary to Holocene volcanic rocks, the North Cascades are composed primarily of Mesozoic crystalline and metamorphic rocks.[38] The exposed rocks which are found in North Cascades National Park predate the middle Devonian and are approximately 400 million years old.[39] Much harder and more durable than the newer volcanic rocks of the southern Cascades, the North Cascades are consequently more rugged, with steep terrain being the norm due to heavy erosion from water and ice.[40] Apparently still rising, the North Cascades originally formed from the jumbled masses of various rock structures that had their origination point thousands of miles to the south some 90 million years ago. By 40 million years ago, the heavier basaltic rocks of the ocean floor had started to push the lighter granitic rocks that are the core of the park's mountains upward, a process that is ongoing.[41] Continued rising in conjunction with erosion from water and ice has created deep valleys and consequently, the vertical relief is significant, averaging between 4,000 and 6,000 ft (1,200 and 1,800 m), which is comparable to much taller mountain ranges.[40]

Mountains

The tallest mountain in North Cascades National Park is Goode Mountain at 9,220 ft (2,810 m).[42] Goode Mountain is in a remote backcountry region of the southern section of the park.[43] Near Goode Mountain are several other peaks that exceed 9,000 ft (2,700 m) including Buckner Mountain (9,114 ft (2,778 m))[44] and Mount Logan (9,087 ft (2,770 m)).[45] Just under 9000 feet, about 5 miles (8.0 km) northeast of Goode Mountain, is Black Peak (8,970 ft (2,730 m)). Other prominent peaks in the southern section of the park include Boston Peak (8,894 ft (2,711 m)),[46] Eldorado Peak (8,868 ft (2,703 m))[47] and Forbidden Peak (8,815 ft (2,687 m)).[48]

The northern region of the park contains the Picket Range, a subrange of the Skagit Range, which is in turn a subrange of the North Cascades.[49] The Picket Range has numerous spires with ominous names such as Mount Fury, Mount Challenger, Poltergeist Pinnacle, Mount Terror, Ghost Peak and Phantom Peak, all of which exceed 8,000 ft (2,400 m). The Picket Range is only 6 mi (9.7 km) long yet contains 21 peaks over 7,500 ft (2,300 m).[49] North of the Picket Range and near the border with Canada lie Mount Redoubt (8,969 ft (2,734 m)), Mount Spickard (8,979 ft (2,737 m)) and the spires of the Mox Peaks (8,630 ft (2,630 m)).[50] Isolated and dominating the northwestern reaches of the park lies the oft photographed Mount Shuksan (9,131 ft (2,783 m)), which towers more than 8,400 ft (2,600 m) above Baker Lake only 6 mi (9.7 km) to the south.[51]

Water features

500 lakes and ponds are located within North Cascades National Park complex.[52]

Glaciers

With approximately 312 glaciers, North Cascades National Park has the most glaciers of any U.S. park outside Alaska and a third of all the glaciers in the lower 48 states are located in the park.[53] Counting a few glaciers in the adjoining National Recreation Areas, the North Cascades National Park Complex glaciers covered an expanse totalling 27,000 acres (110 km2) as of 2009.[54] The dense concentration and relative ease of access to the North Cascade glaciers brought about some of the earliest scientific series of studies regarding glaciology in the U.S. Beginning in 1955, The University of Washington sponsored Richard C. Hubley to undertake annual aerial photography expeditions designed to capture images of the glaciers and to show any alterations that might be occurring.[55] In 1960, Austin Post expanded the aerial coverage to include other regions and he also used ground based imagery to augment the research. In 1971, based on the photographic imagery and other data collected since 1955, Post and others wrote a groundbreaking report that documented the number and scale of glaciers in the North Cascades.[39] At the time of Austin Post's inventory, their study concluded that some North Cascades glaciers had experienced a period of minor growth or equilibrium in the mid-20th century, after undergoing decades of retreat. The study concluded that annual glacial melt due to seasonal variations has a significant influence on river levels, accounting for about 30 percent of the late summer water flow, which directly impacted the supported ecosystems such as salmon fisheries.[39]

The National Park Service (NPS), United States Geological Survey (USGS) and private researchers such as Mauri S. Pelto, who has led the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project since 1984, have continued research on North Cascade glaciers.[56] Since 1993, the NPS has conducted rigorous studies on four park glaciers: Noisy Creek, Silver, North Klawatti and Sandalee Glaciers.[57] The NPS research indicated that these four glaciers experienced rapid decrease in volumes between 1993 and 2011.[58] In 1998, a NPS and Portland State University aerial photographic inventory showed a 13 percent loss in parkwide glacial volume since Austin Post's inventory in 1971.[59] The NPS states that in the last 150 years since the end of the Little Ice Age, a period of several centuries in which the earth experienced a cooling phase, glacial ice volumes in the North Cascades have been reduced by 40 percent.[59] This loss of glacial ice has contributed to decreased melt in the summer and in just the Thunder Creek watershed alone, this decreased runoff amounts to a loss of 30 percent of the summer streamflow.[53]

Boston Glacier, on the north slope of Boston Peak, is the largest glacier in the park, measured in 1971 to have an area of 1,730 acres (7.0 km2).[42] Other large glaciers include East Nooksack and Sulphide Glaciers on Mount Shuksan, McAllister and Inspiration Glaciers on Eldorado Peak, Redoubt Glacier on Mount Redoubt, Neve Glacier on Snowfield Peak, and Challenger Glacier on Mount Challenger.

Ecology

Variation in rock and soil types, exposure, slope, elevation, and rainfall is reflected in the diverse plant life. Eight distinctive life zones support thousands of different plant species in the North Cascades greater ecosystem.

Flora

No other National Park surpasses North Cascades National Park's over 1,630 vascular plant species recorded. Estimates of non-vascular and fungal species could more than double the number of plant species in the North Cascades.[60] The park contains an estimated 236,000 acres (960 km2) of old-growth forests.[61] The biodiversity of the area is threatened by global climate change and invasive exotic plant species.[60] These exotic plants thrive by using man-made structures such as roads and trails.[60] These invasive plants include the diffuse knapweed (Centaurea diffusa) and reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea).[62]

Fauna

The park also has a diversity of animal species, including timber wolf, coyote, bobcat, Canadian lynx, cougar, moose, elk, river otter, golden eagle, hoary marmot, bald eagle, pika, wolverine, mountain goat, grizzly bear, and black bear.[63] The park is home to 75 species of mammals and 200 species of birds that either pass through or use the North Cascades for a breeding area. There are also 11 species of fish on the west side of the Cascades.[63] Examples of amphibian species occurring in the park include the western toad (Bufo boreas) and the rough-skinned newt (Taricha granulosa).[64]

Tourism

Attractions

Nearly all of the national park is protected as the Stephen Mather Wilderness, so there are few maintained buildings and roads within the North and South units of the Park. The park is most popular with backpackers and mountain climbers. One of the most popular destinations in the park is Cascade Pass, which was used as a travel route by Native Americans. It can be accessed by a four-mile (6 km) trail at the end of a gravel road. The North and South Picket Ranges, Mount Triumph, as well as Eldorado Peak and the surrounding mountains, are popular with climbers due to glaciation and technical rock. Mount Shuksan, in the northwest corner of the park, is one of the most photographed mountains in the country and the second highest peak in the park 9,127 ft or 2,782 m.

Access

Although a couple of gravel roads open to the public enter the park (Cascade River Road beginning at Marblemount off HWY #20 and the Upper Stehekin Valley Road accessed from Stehekin via tour-boat from Chelan), most automobile traffic in the region travels on the North Cascades Highway (Washington State Route 20), which passes through the Ross Lake National Recreation Area.

The nearest large town on the west side of the park is Sedro-Woolley, Washington, while Winthrop lies to the east. Chelan is located at the southeastern end of Lake Chelan where east-side access to the NCNP from Stehekin serves the Eastern Washington communities.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.

- ↑ "North Cascades National Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- 1 2 "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- 1 2 Apostol, Dean; Marcia Sinclair (November 5, 2006). Restoring the Pacific Northwest: The Art and Science of Ecological Restoration in Cascadia. Island Press. p. 248. ISBN 9781610911030. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ McManamon, Francis P.; Linda S. Cordell; Kent G. Lightfoot; George R. Milner (December 2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-313-33184-8. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ Mierendorf, Robert. "Cultural History". North Cascades Institute. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- 1 2 Mierendorf, Robert. "Archeology at Cascade Pass" (pdf). North Cascades Resource Brief. National Park Service. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ↑ "History and Culture". National Park Service. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Thompson, Erwin N. (June 11, 2008). "The Indians". North Cascades History Basic Data. National Park Service. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Luxenberg, Gretchen A. (February 7, 1999). "Marketing the Wilderness: Development of Commercial Enterprises". Historic Resource Study. National Park Service. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Thompson, Erwin N. (June 11, 2008). "Fur Trading and Trapping". North Cascades History Basic Data. National Park Service. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Luxenberg, Gretchen A. (February 7, 1999). "Early Impressions: Euro-American Explorations and Surveys". Historic Resource Study. National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Thompson, Erwin N. (June 11, 2008). "International Boundary". North Cascades History Basic Data. National Park Service. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Geology Fieldnotes". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Settlers and Explorers". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Erwin N. (June 11, 2008). "Mining". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Miners". National Park Service. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- 1 2 "The Builders". History and Culture. National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ Louter, David (April 14, 1999). "Land Use and Protection". Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History. National Park Service. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Thompson, Erwin N. (June 11, 2008). "The Public Domain". North Cascades History Basic Data. National Park Service. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Louter, David (April 14, 1999). "A Wilderness Park". Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History. National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Louter, David (April 14, 1999). "Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park". Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History. National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ Louter, David (April 14, 1999). "Administration". Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History. National Park Service. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- 1 2 "Washington Park Wilderness Act of 1988". National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ↑ North Cascades National Park Complex (pdf) (Map). National Park Service. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "North Cascades National Park 2012 Business Plan" (pdf). National Park Service. Spring 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ↑ "The National Park System, Caring for the American Legacy". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Trail Guide". National Park Service. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Mount Baker Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Noisy-Diobsud Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Glacier Peak Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Nature and Science". National Park Service. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- 1 2 "Natural Features & Ecosystems". National Park Service. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "North Cascades Geology". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Glaciers / Glacial Features". National Park Service. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Public Transportation". National Park Service. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Geology of Washington - Northern Cascades". Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Post, Austin; Don Richardson; Wendell V. Tangborn; F. L. Rosselot (1971). "Inventory of Glaciers in the North Cascades, Washington". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- 1 2 Tabor, Rowland; Ralph Haugerud (May 14, 1999). Geology of the North Cascades: A Mountain Mosaic. Mountaineers Books. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0898866230. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Geologic Formations". National Park Service. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- 1 2 "North Cascades Student Guide" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ↑ Smoot, Jeff (January 1, 2002). Climbing Washington's Mountains. FalcomGuides. p. 89. ISBN 978-0762710867.

- ↑ Smoot, Jeff (January 1, 2002). Climbing Washington's Mountains. FalconGuides. p. 86. ISBN 978-0762710867.

- ↑ Smoot, Jeff (January 1, 2002). Climbing Washington's Mountains. FalcomGuides. pp. 93–97. ISBN 978-0762710867.

- ↑ Beckey, Fred (January 15, 2003). Cascade Alpine Guide: Climbing and High Routes: Stevens Pass to Rainy Pass. The Mountaineers Books. p. 331. ISBN 978-0898868388.

- ↑ "Eldorado Peak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Forbidden Peak". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- 1 2 Beckey, Fred (Jun 1, 2008). Cascade Alpine Guide; Rainy Pass to Fraser River. The Mountaineers Books. pp. 96–100. ISBN 9781594854309.

- ↑ Goldman, Peggy (March 30, 2004). Washington's Highest Mountains: Basic Alpine and Glacier Routes. Wilderness Press. pp. 43–49. ISBN 978-0899972909.

- ↑ "Rivers and streams". National Park Service. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Lakes and ponds". National Park Service. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- 1 2 Riedel, Jon; Mike Larrabee; Sharon Brady; Niki Bowerman; Rob Burrows; Steve Dorsch; Joanie Lawrence; Jeannie Wenger. "Glacier Monitoring Program". National Park Service. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ Riedel, Jon; Michael Larrabee (August 2011). "North Cascades National Park Complex Glacier Mass Balance Monitoring Annual Report, Water Year 2009" (pdf). Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2011/483. National Park Service. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ Post, Austin; Edward R. LaChapelle (March 1, 2000). Glacier Ice. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0802083753. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ Pelto, Mauri (September 2007). "Vanishing Glaciers" (pdf). Washington Trails. Washington Trails Association: 1–4. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Glaciers Selected for Monitoring". National Park Service. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Recent Trends in Glacial Volume". National Park Service. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- 1 2 "Long Term Trends". National Park Service. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Plants". United States National Park Service: North Cascades National Park Service Complex. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ↑ Bolsinger, Charles L.; Waddell, Karen L. (1993). "Area of old-growth forests in California, Oregon, and Washington" (PDF). United States Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Resource Bulletin PNW-RB-197.

- ↑ "Non-native plants". North Cascades National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- 1 2 Kefauver, Karen (September 15, 2010). "North Cascades National Park: Wildlife". GORP. Orbitz. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- ↑ Rawhouser, Ashley K.; Holmes, Ronald E.; Glesne, Reed S. (2009). "A Survey of Stream Amphibian Species Composition and Distribution in the North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington State" (PDF).

- Post, A.; D. Richardson; W.V. Tangborn; F.L. Rosselot (1971). "Inventory of glaciers in the North Cascades, Washington". USGS Prof. Paper. 705-A: A1–A26.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to North Cascades National Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for North Cascades National Park. |

- Official North Cascades National Park website

- Education: North Cascades Institute

- Glacier Research: North Cascade Glacier Climate Project reports

- Conservation: The North Cascades Conservation Council

- Expansion project: The American Alps Legacy Project seeks to expand and complete the Park as envisioned by its founders

- The North Cascades Oral History Project - University of Washington Digital Collection