Nauru Regional Processing Centre

.jpg) Part of the Nauru offshore processing facility in September 2012 | |

| Location | Meneng District, Nauru |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 0°32′28″S 166°55′48″E / 0.541°S 166.930°ECoordinates: 0°32′28″S 166°55′48″E / 0.541°S 166.930°E |

| Status | Operational |

| Population |

|

| Opened | 2001 |

The Nauru Regional Processing Centre is one of many offshore Australian immigration detention facilities, located on the South Pacific island nation of Nauru. The centre is operated by Broadspectrum (formerly Transfield Services) on behalf of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection a department of the Government of Australia that is responsible for immigration, citizenship and border control. The use of immigration detention facilities is part of a policy of mandatory detention in Australia. The Nauru facility was opened in 2001 as part of the Howard government's Pacific Solution. The centre was suspended in 2008 to fulfil an election promise by the Rudd government, but was reopened in August 2012 by the Gillard government after a large increase in the number of maritime arrivals by asylum seekers and pressure from the Abbott opposition.[2] Current Coalition and Labor Party policy states that because all detainees attempted to reach Australia by boat, they will never be settled in Australia.[3] Many detainees have since been returned to their countries of origin, including Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Sudan, Afghanistan and "unknown" destinations.[4] Asylum-seekers found to be genuine refugees have been detained on the island since mid-2013.[5]

Conditions

The conditions at the Nauru detention centre were initially described as harsh with only basic health facilities.[6] In 2002, detainees deplored the water shortages and overcrowded conditions.[6] There were only very limited education services for children.[6]

On 19 July 2013 there was a major riot in the detention centre. Several buildings were destroyed by fire, and damage was estimated at $60 million.

Hunger strikes and self-harm, including detainees sewing their lips together, have been reported as occurring at the facility.[7] Attempted suicides were also reported.[8] Medical staff have been provided by International Organization for Migration.

An overwhelming sense of despair has been repeatedly expressed by detainees because of the uncertainty of their situation and their remoteness from loved ones.[9] In 2013, a veteran nurse described the detention centre as 'like a concentration camp'.[8]

In 2015, several staff members from the detention centre wrote an open letter claiming that multiple instances of sexual abuse against women and children had occurred.[10] The letter claimed that the Australian government had been aware of these abuses for over 18 months.[11] This letter added weight to the Moss review which found it possible that "guards had traded marijuana for sexual favours with asylum seeker children".[12] [13][14]

Media access

Media access to the island of Nauru, and the RPC in particular, is tightly controlled by the Nauruan government. In January 2014, the Nauru government announced it was raising the cost of a media visa to the island from AUD $200 to $8,000, non-refundable if the visa was not granted.[15] Since then journalists from Al Jazeera, the ABC, SBS and The Guardian have stated that they have applied for media visas with no success. The last journalist to visit the island before the commencement of Operation Sovereign Borders was Nick Bryant of the BBC.[16]

In October 2015, Chris Kenny, a political commentator for The Australian, became the first Australian journalist to visit Nauru in over 18 months. While on the island, Kenny interviewed a Somalian refugee known as "Abyan", who alleged she had been raped on Nauru and requested an abortion of the resulting pregnancy. Pamela Curr of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre accused Kenny of forcing his way into Abyan's quarters to speak to her—a claim Kenny strongly denied.[16] In June 2016, the Press Council of Australia dismissed a complaint regarding the wording of his article and its headline.[17]

In June 2016, a television crew from A Current Affair was granted access to the island and the centre. Reporter Caroline Marcus presented asylum seekers housed in fully equipped demountable units, and provided with their own television, microwave, airconditioning units and refrigerator. In a column in The Daily Telegraph and an interview with ACA host Tracy Grimshaw, Marcus denied that there were any conditions on the crew's visit, and stated that the Australian government had been unaware of the crew being granted visas until after they had arrived on the island.[18]

History

The establishment of an offshore processing centre on Nauru was based on a Statement of Principles, signed on 10 September 2001 by the President of Nauru, René Harris, and Australia's then-Minister for Defence, Peter Reith. The statement opened the way to establish a detention centre for up to 800 people and was accompanied by a pledge of A$20 million for development activities. The initial detainees were to be people rescued by the MV Tampa (see Tampa affair), with the understanding that they would leave Nauru by May 2002. Subsequently, a memorandum of understanding was signed on 11 December, boosting accommodation to 1,200 and the promised development activity by an additional $10 million.[19]

Initial plans were for asylum seekers to be housed in modern, air-conditioned housing which had been built for the games of the International Weightlifting Federation. This plan was changed after landowners' requests for extra compensation were rejected.[19]

Two camps were built.[20] The first camp, called "Topside", was at an old sports ground and oval in the Meneng District (0°32′26″S 166°55′47″E / 0.540564°S 166.929703°E). The second camp, called "State House", was on the site of the old Presidential quarters also in the Meneng District (0°32′51″S 166°56′23″E / 0.547597°S 166.939697°E).[19][21][22][23]

A month-long hunger strike began on 10 December 2003.[24] It included mostly Hazara from Afghanistan rescued during the Tampa affair, who were protesting for the review of their cases.

By July 2005, 32 people were detained in Nauru as asylum seekers: 16 Iraqis, 11 Afghans, 2 Iranians, 2 Bangladeshis, and 1 Pakistani.[25] All but two Iraqis were released to Australia, the last group of 25 leaving on 1 November 2005. The remaining two Iraqis stayed in custody for over a year. The last one was finally accepted by an undisclosed Scandinavian country after five years in detention, in January 2007. The other was in an Australian hospital at the time, and was later given permission to remain in Australia while his asylum case was being decided. In September 2006, a group of eight Burmese Rohingya men were transferred there from Christmas Island.[26] On 15 March 2007 the Australian Government announced that 83 Tamils from Sri Lanka would be transferred from Christmas Island to the Nauru detention centre.[27] They arrived in Nauru by the end of the month.

In December 2007, newly elected Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced that his country would no longer make use of the Nauru detention centre, and would put an immediate end to the "Pacific Solution". The last remaining Burmese and Sri Lankan detainees were granted residency rights in Australia.[28][29] Nauru reacted with concern at the prospect of potentially losing much-needed aid from Australia.[30]

Re-opening

In August 2012, Nauru detention centres were re-opened to process asylum seekers arriving by boat in Australia. The first group arrived the following month.[31][32] The re-opening of the centres sparked criticism of Australia's Labor Government after the United Nations refused to assist the government on the mandatory measures.[32][33] In November 2012, an Amnesty International team visited the camp and described it as "a human rights catastrophe ... a toxic mix of uncertainty, unlawful detention and inhumane conditions".[34][35]

July 2013 riot

On 19 July 2013 a riot occurred at the detention centre and caused $60 million damage. Police and guards had rocks and sticks thrown at them. Four people were hospitalised, though their injuries were minor.[36] Other people were treated for bruising and cuts.[37] The riot began at 3 pm when the detainees staged a protest.[38] Up to 200 detainees escaped and about 60[39] were held overnight at the island's police station.[40] Several vehicles[41] and buildings including accommodation blocks for up to 600 people, offices, dining room, and the health centre were destroyed by fire. This is about 80 percent of the centre's buildings.[36][39] 129 of 545 male detainees were identified as being involved in the rioting and were detained in the police watch house.[36]

Opening of the centre

In October 2015 Nauru declared that the asylum seekers housed in the detention centre now had freedom of movement around the island. Given reports that three women had been raped and numerous other assaults have taken place against asylum seekers it was reported that this may actually increase the amount of danger to them.[42]

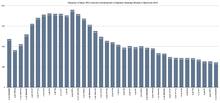

Numbers

As of 31 October 2016 there are 390 asylum seekers held in the detention centre, of which 50 are women and 45 are children.[1]

See also

- Asylum in Australia

- Manus Island Regional Processing Centre

- List of Australian immigration detention facilities

References

- 1 2 "Immigration Detention and Community Statistics Summary 31 October 2016" (PDF). Government of Australia Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 31 October 2016. Retrieved 2 Dec 2016.

- ↑ http://www.news.com.au/national/tony-abbott-pushes-for-nauru-asylum-seeker-option-on-visit-to-island/story-e6frfkvr-1226073880300

- ↑ http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1314/AsylumPolicies

- ↑ http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/Offshore

- ↑ http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/Offshore

- 1 2 3 Mares, Peter (2002). Borderline: Australia's Treatment of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the Wake of the Tampa. UNSW Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 0868407895. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "Nauru detainees stitch lips together". ABC News. Australia. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- 1 2 AAP (5 February 2013). "Nurse Marianne Evers likens Nauru detention centre to concentration camp". news.com.au. News Limited. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Gordon, Michael (2007). "The Pacific Solution". In Lusher, Dean; Haslam, Nick. Yearning to Breathe Free: Seeking Asylum in Australia. Federation Press. p. 79. ISBN 1862876568. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/7290

- ↑ http://www.skynews.com.au/news/top-stories/2015/04/07/nauru-workers-say-govt-knew-about-abuse.html

- ↑ "Report condemns Nauru detention centre conditions". News. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ "Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection" (PDF). Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ↑ http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/rapes-sexual-assault-drugs-for-favours-in-australias-detention-centre-on-nauru-independent-moss-review-20150320-1m46za.html

- ↑ "Nauru media visa fee hike to 'cover up harsh conditions at Australian tax-payer funded detention centre'". ABC News. 9 January 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Exclusive Nauru access for The Australian". Media Watch. ABC. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "Adjudication 1679: Complainant/The Australian (June 2016)". Press Council of Australia. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Schipp, Debbie (21 June 2016). "Inside Nauru: 'You make a nice prison, it's still a prison'". news.com.au. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Oxfam (February 2002). "Adrift in the Pacific: The Implications of Australia's Pacific Refugee Solution" (PDF). Oxfam: 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2007.

- ↑ Dobell, Graeme; Downer, Alexander (11 December 2001). "Nauru: holiday camp or asylum hell?". PM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 February 2007.

- ↑ Frysinger, Galen R. (16 July 2004). "Sketch map of Nauru". Archived from the original on 16 July 2004. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ↑ Bartlett, Andrew (7 August 2003). "Government-sponsored child abuse at the Nauru detention centres". On Line Opinion.

- ↑ Cloutier, Bernard (1998). "Nauru". Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ↑ Kneebone, Susan; Felicity Rawlings-Sanaei (2007). New Regionalism and Asylum Seekers: Challenges Ahead. Berghahn Books. p. 180. ISBN 1845453441. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ↑ "N A U R U". Nauruwire.org. 31 January 1968. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ↑ (30 September 2006) Samantha Hawley. Burmese asylum seekers likely to achieve refugee status. AM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "Asylum seekers to be sent to Nauru". ABC Online News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- ↑ « Pacific solution ends but tough stance to remain », Craig Skehan, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 2007

- ↑ « Burmese detainees granted asylum », Cath Hart, The Australian, 10 December 2007

- ↑ « Nauru fears gap when camps close », The Age, 11 December 2007

- ↑ Grubel, James Australia reopens asylum detention in Nauru tent city 14 September 2012 Reuters Retrieved 10 October 2015

- 1 2 "Work needed on Nauru detention centre". BigPond News. 19 September 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ↑ (24 August 2012) Ben Packham. UN won't work with Labor on asylum-seeker processing on Nauru and Manus Island. The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "Nauru Camp A Human Rights Catastrophe With No End in Sight" (PDF). Amnesty International. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ↑ "Amnesty International slams Nauru facility". Amnesty International. 20 November 2012. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Photos of riot damage at Nauru detention centre released by Department of Immigration". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 21 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ "Asylum seekers in police custody after riot at Nauru detention centre". ABC (Australia). 21 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ Hall, Bianca; Flitton, Daniel (19 July 2013). "Policeman 'held hostage' as rioting breaks out on Nauru". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- 1 2 Staff (20 July 2013). "Nauru detention centre riot 'biggest, baddest ever'". The Age. AAP. Retrieved 20 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Police attend full-scale riot at asylum seeker detention centre on Nauru". ABC (Australia). 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Dozens charged after Nauru detention riot". news.com.au. 21 July 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ Allard, Tom Nauru's move to open its detention centre makes it "more dangerous" for asylum seekers October 9, 2015 Sydney Morning Herald Retrieved 10 October 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nauru Regional Processing Centre. |

- Department of Foreign Affairs and trade – MOU on Asylum Seekers Signed with Nauru

- Pictures inside the detention centre in the submission by Ms Elaine Smith to the Inquiry into the provisions of the Migration Amendment (Designated Unauthorised Arrivals) Bill 2006