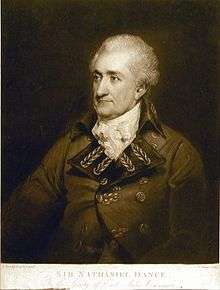

Nathaniel Dance

| Sir Nathaniel Dance | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

20 June 1748 London, England |

| Died |

25 March 1827 (aged 78) Enfield, England |

| Allegiance |

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Service/branch | Honourable East India Company |

| Years of service | 1759–1804 |

| Rank | Commodore |

| Battles/wars |

French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic Wars Battle of Pulo Aura |

| Awards | Knighthood |

Sir Nathaniel Dance (20 June 1748 – 25 March 1827) was an officer of the Honourable East India Company who had a long and varied career on merchant vessels, making numerous voyages to India and back with the fleets of East Indiamen. He was already aware of the risks of the valuable ships he sailed on being preyed on by foreign navies, having been captured by a Franco-Spanish fleet in 1780 during the East Indies campaign of the American War of Independence. His greatest achievement came during the Napoleonic Wars, when having been appointed commodore of one of the company's fleets, he came across a French squadron under Rear-Admiral Comte de Linois, which was raiding British shipping in the area. Through skilful seamanship and aggressive tactics he fooled the French commander into thinking that the British convoy was escorted by powerful naval forces, and the French decided not to risk attacking the convoy. Dance compounded the deception by taking his lightly armed merchants and chasing the French away, despite the considerable disparity of force. Having saved the convoy from almost certain destruction, Dance was hailed as a hero, lavishly rewarded with money and a knighthood, and spent the last years of his life in comfortable retirement.

Family and early life

Dance was born in London on 20 June 1748, the son of James Dance and his wife Elizabeth.[1] James Dance was a successful lawyer of the city, but shortly after the birth of Nathaniel, he abandoned his wife to live with an actress, and in time established himself as a successful actor and playwright in Drury Lane.[2] Elizabeth Dance and her family were instead cared for by James's father, and Nathaniel's paternal grandfather, George Dance the Elder, a prominent architect for the City of London.[1][2] Nathaniel lived with his grandfather until 1759, when he went to sea under the patronage of Nathaniel Smith, a high-ranking official in the Honourable East India Company.[1][2] With Smith's support, Dance rose through the ranks of the service, by 1780 having made eight voyages to India, as well as one to the Mediterranean and one to the West Indies.[1][2] While making his ninth voyage to India as first officer on Royal George when a combined Spanish and French fleet captured his ship in the Action of 9 August 1780.[a] Dance was taken to Spain, where he spent six months on parole.[1][3] He became commander of the Lord Camden in January 1787, making another four voyages to India aboard her, before being appointed commander of a new ship, the Earl Camden, in which he sailed to China in January 1803.[1][3]

Voyage home

The Earl Camden sailed from Canton with the rest of the fleet on 31 January 1804, bound for England.[1][3] By virtue of his seniority Dance was appointed commodore of the fleet of 11 "country" ships, and 16 East Indiamen.[4][5] The fleet that had been assembled was the richest to date, carrying cargoes with an estimated value of £8 million,[4] (approximately £635 million in present-day terms[6]). Dance had been taken seriously ill at Bombay during the outward voyage, but had recovered in time to sail with the convoy.[3] The fleet did not have any naval escorts, and though the East Indiamen were heavily armed for merchants, carrying nominal batteries of between 30 and 36 guns, they were no match for disciplined and professional naval forces.[4] Not all of their listed armament was always carried, but to give the illusion of greater strength, fake gunports were often painted on the hulls, in the hope of distant observers mistaking them for 64-gun ships of the Royal Navy.[4] By the time the fleet approached the Strait of Malacca on 14 February, Dance's convoy had swelled to include 16 East Indiamen, 11 country ships, a Portuguese merchant ship from Macau and a vessel from Botany Bay in Australia.[7] Although the HEIC had provided the small, armed brig Ganges as an escort, this vessel could only dissuade pirates; it could not hope to confront a French warship.[8] As they neared the entrance to the straits suspicious sails were sighted in the south west.[1] Dance sent some of his ships to investigate, and it was soon discovered that this was Linois's squadron, consisting of the 74-gun Marengo, the two heavy frigates Sémillante and Belle Poule, the corvette Berceau, and the Dutch brig Aventurier.[1][4]

The battle

Having ascertained the identity of the ships Dance signalled for his merchants to form the line of battle, and continued their heading, while the French closed, but made no move to attack.[1][4] Dance used the delay to gather his ships together so the stronger East Indiamen stood between the French and the weaker country ships.[9] The merchants continued on towards the straits, followed by Linois, who was trying to gauge the strength of the convoy. There were more ships in the convoy than he had expected, and taken in by Dance's manoeuvres and the painted gunports, Linois suspected that several warships were escorting them.[10] He seemed to be confirmed in his suspicions when at dawn on 15 February, both forces raised their colours. Dance ordered the brig Ganges and the four lead ships to hoist blue ensigns, while the rest of the convoy raised red ensigns. By the system of national flags then in use in British ships, this implied that the ships with blue ensigns were warships attached to the squadron of Admiral Peter Rainier, while the others were merchant ships under their protection.[11]

With the French still appearing reluctant to attack on the morning of 16 February, Dance ordered his ships to increase their speed by breaking into a sailing formation. This had the effect of making the convoy appear less intimidating and Linois decided to attack.[12] By the afternoon the French were observed to be moving to cut off the rearmost ships of the convoy. Dance promptly hoisted colours, and ordered his largest ships, led by the East Indiamen Royal George, Ganges and his own ship, Earl Camden, to come about and close on the French.[1][13] Advancing under full sail, they endured the fire of the French as they closed, before firing broadsides at close range. At this the French abandoned their attack, turned, and fled under a press of sail.[1][13] Dance hoisted the signal for a general chase and his merchant fleet pursued the French squadron for two hours, before Dance broke off and returned on his original heading.[1][13] The fleet resumed their course towards the Malacca Strait, and having met two British ships of the line from Admiral Peter Rainier's fleet on 28 February, were escorted as far as Saint Helena.[b][13][14] There the convoy met with other British merchants, and were escorted to Britain by Royal Navy warships, arriving in August 1804.[14][15]

Rewards

The achievement of a convoy of merchants not only escaping without loss from a French squadron, but going so far as to attack, drive off, and then pursue their would-be predators, was widely hailed as a signal victory.

The Naval Chronicle declared:

We cannot sufficiently express our opinion of the coolness, intrepidity, and skill, with which the Commander of this Fleet, unaccustomed as he was to the practice of naval engagements, provided against every emergency, and prepared his plans, either for attack or defence, as the manoeuvres of the French Admiral might render it expedient for him to adopt either the one of the other. His conduct was worthy of the experience and science of our most approved and veteran Admirals, while the ardour and promptitude with which his orders were obeyed and his plans executed by the several Captains under his command, may have been rivalled, but can scarcely be exceeded in the most renowned of our naval exploits.[16][17]

Dance received £5,000 from the Bombay Insurance Company (approximately £338,000 in present-day terms[6]), a pension of £500 a year (approximately £34,000 a year in present-day terms[6]), plate worth 200 guineas from the Honourable East India Company, a ceremonial sword worth £100, and a silver vase.[14][15][18] His captains were also rewarded. Captain Timmins of the Royal George received £1000, a sword and plate, while the other captains received £500, and a sword and plate, with money being paid to the officers and seaman under their command, with an ordinary seaman receiving £6 (approximately £500.00 in present-day terms[6]).[15]

Dance himself credited the actions of those under his command as being largely responsible for the victory, writing in reply to the award from the Bombay Insurance Company:

Placed, by the adventitious circumstances of seniority of service and absence of convoy, in the chief command of the fleet intrusted to my care, it has been my good fortune to have been enabled, by the firmness of those by whom I was supported, to perform my trust not only with fidelity, but without loss to my employers. Public opinion and public rewards have already far outrun my deserts; and I cannot but be sensible that the liberal spirit of my generous countrymen has measured what they are pleased to term their grateful sense of my conduct, rather by the particular utility of the exploit, than by any individual merit I can claim.— Nathaniel Dance, quoted in William James' The Naval History of Great Britain during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, Volume 3, 1827, [19]

Dance received a knighthood and went into a comfortable retirement, dying at Enfield on 25 March 1827 at the age of 78.[14]

Notes

a. ^ According to Tracy, Dance was captured while commanding his first ship, Dance having reached the rank of commander in 1780.[1] Laughton however implies that Dance did not command his first ship, the Lord Camden, until 1787,[20] while the Naval Chronicle states 'From the year 1759 to 1787, he passed successively through all the gradations of professional service ... to the rank of commander'.[2]

b. ^ These were HMS Sceptre and HMS Albion.[12]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Tracy. Who's who in Nelson's Navy. p. 112.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clarke. The Naval Chronicle. pp. 346–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Clarke. The Naval Chronicle. p. 348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brown. Ill Starred Captains. p. 439.

- ↑ "Dance, Sir Nathaniel (1748-1827)". Dictionary of National Biography. 1888. p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ James. The Naval History of Great Britain. 3. p. 248.

- ↑ Woodman. The Sea Warriors. p. 194.

- ↑ Roger. The Command of the Ocean. p. 546.

- ↑ James. The Naval History of Great Britain. 3. p. 249.

- ↑ Clowes. The Royal Navy, A History. p. 337.

- 1 2 Woodman. The Sea Warriors. p. 195.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown. Ill Starred Captains. p. 440.

- 1 2 3 4 Tracy. Who's who in Nelson's Navy. p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Brown. Ill Starred Captains. p. 441.

- ↑ Tracy. Who's who in Nelson's Navy. pp. 111–2.

- ↑ Clarke. The Naval Chronicle. pp. 348–9.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15767. p. 6. 29 December 1804. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ↑ James. The Naval History of Great Britain. 3. p. 252.

- ↑ "Dance, Sir Nathaniel (1748-1827)". Dictionary of National Biography. 1888. p. 11.

References

- Brown, Anthony Jarrold (2008). Ill Starred Captains: Flinders & Baudin. Fremantle Press. ISBN 1-921361-29-8.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Editor: Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 3, 1800–1805. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7.

- Laughton, J. K. (1888). "Dance, Sir Nathaniel (1748-1827)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 14. Oxford University Press.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Command of the Ocean. Allan Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9411-8.

- Stanier, James; Jones, Stephen (1805). The Naval Chronicle. 12. London: J. Gold.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-244-5.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.