Nathan Paget

| Nathan Paget | |

|---|---|

| Born |

March 1615 Blackley, Manchester. |

| Died |

January 1679 London |

| Residence | Coleman Street, London. |

| Nationality | English |

| Fields | Bubonic plague, rickets. |

| Institutions | University of Cambridge, College of Physicians. |

| Education | University of Edinburgh, University of Leyden. |

| Thesis | 'De Peste' (1639) |

| Known for |

Collaborative work on rickets. Radical political and religious interests. Association with John Milton. |

| Influences | Daniel Whistler |

| Influenced | Francis Glisson, Samuel Hartlib, Elias Ashmole. |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Cromwell, cousin of Oliver Cromwell. |

| Children | Childless |

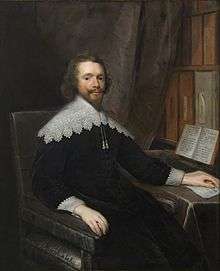

Nathan Paget (1615–1679) was an English physician, active during the English Civil War, under the Commonwealth and the Protectorate, and after the Restoration. Despite being a mainstay of a generally conservative profession, he was interested in the experimental methods of the Enlightenment. Although from a strongly Presbyterian background, he seems to have developed radical political and religious sympathies.

Origins

Paget was baptised at Manchester on 31 March 1615.[1] He was the son of

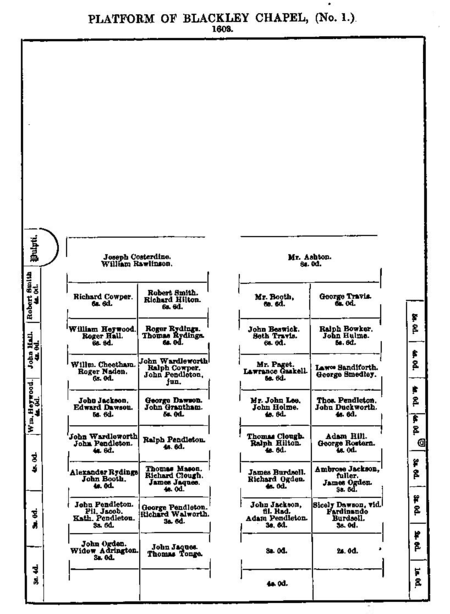

- Thomas Paget - at the time a minister at Blackley, although he later served in Amsterdam, Shrewsbury and Stockport.[2] Blackley chapel was subsidiary to St Mary's Church, Manchester, a great collegiate church with many subsidiary chapels across its vast parish of more than 35,000 acres.[3] Thomas Paget had proceeded to M.A. only in 1612[1] and was recruited to serve at Blackley by William Bourne, a Puritan fellow of St Mary's, who was particularly interested in the quality of preaching at the outlying chapels.[4] Thomas Paget's elder brother and Nathan's uncle was John Paget, a Presbyterian theologian and controversialist who had gone into exile in 1605 and was serving as pastor of the English Reformed Church, Amsterdam.[5] They probably belonged to the Paget family of Rothley in Leicestershire, although their parentage is unknown.

Thomas Paget already had family connections with Nantwich, as John Paget had served as Rector there 1598–1604[5] and in 1602 had married the widow Briget Thrushe née Masterson,[8] who belonged to the oldest of Nantwich's major families.[9] Nathan's parents were married at St Mary's Church, Nantwich on 6 April 1613.[10] He was their first child and had two surviving younger sisters, Dorothy and Elizabeth.

Early life and education

Nathan Paget was part of a combative, sometimes persecuted, Puritan family from the outset and his early experience reflected this. As early as 1617 his father emerged as a leader of the Puritan opposition to Thomas Morton, the Bishop of Chester, and was referred to the Court of High Commission,[11] although at this point he emerged with little more than a warning and substantial expenses to pay. Nathan was educated first at Northwich grammar school (now Sir John Deane's College), where the head was Richard Pigot,[12] a staunch Calvinist who was later head of Shrewsbury School.

The pace of persecution increased with the accession of Charles I and Thomas Paget was under increasing pressure from Morton's successor, John Bridgeman.[13] Nathan's mother, died in 1628 and was buried at Bowdon in Cheshire on 31 August.[14] Bowdon was one of the villages where the Puritan ministers held their monthly exercises[15] and was close to Dunham Massey, the home of the leading Presbyterian layman in Cheshire George Booth,[16] which suggests the family were already feeling the need of protection. With the imposition from 1629 of Thorough, an attempt at absolute monarchy, the situation deteriorated further. In 1631 Thomas Paget was pursued with attachments for fines he had incurred and threatened with imprisonment.[17] He went into hiding and escaped with his family to the Dutch Republic.

They took refuge in Amsterdam, where Thomas assisted his brother John at the English Reformed Church. Nathan's education seems to have advanced rapidly, both formally and informally. He must have entered the University of Edinburgh fairly soon after their flight to the Netherlands, as he graduated MA in 1635.[1] While Scotland was under the same king as England, it had a Presbyterian polity and was outside English law, so it was sufficiently safe and familiar. Thereafter Paget seems to have taken a three-year break from formal study, although it is unlikely he was any less involved in intellectual striving. John Paget was described by Robert, his nephew and adopted son, as having

- rare skill in the languages that conduce unto the understanding of the originall text of the Scriptures; for he could to good purpose and with much ease make use of the Chaldean, Syriack, Rabbinicall, Thalmudicall, Arabick, and Persian versions and commentaries.[18]

To pursue such wide linguistic interests the Pagets must have drawn on the resources of Amsterdam's substantial Jewish community: the Sephardim alone numbered about 800 in 1626 and 1200 in 1655.[19] Nathan took a considerable interest in ancient languages and in later life his library contained several Hebrew Bibles and a Hebrew language Bible concordance.[20] He became part of a philo-semitic, polyglot and polymath circle that overlapped with other intellectual networks across Western Europe. One contact was John Dury, an eirenic Scottish Protestant minister, who had close contacts with the Jewish community. On 5 November 1634 John Paget and his congregation wrote to congratulate him on a recent sermon and invited him again to Amsterdam.[21] A copy of the letter was sent to Samuel Hartlib, a German scientist and polymath who had sought refuge from the Thirty Years' War in England. Hartlib clearly kept up with the Pagets' activities, noting in July 1638 that John was recovering from an illness.[22] John died the following month,[5] although he had effectively retired from leadership of the English Reformed Church the previous year.

With John Paget's death, the Paget family in Amsterdam dispersed. His widow Briget became his literary executor and went to live with her adopted son, Robert, in Dordrecht.[23] Thomas had already taken over as pastor of the English Reformed Church, where he was assisted by Julines Herring, a comrade of the struggles in Cheshire and formerly public preacher in Shrewsbury.[24][25] On 25 November 1638 Nathan entered as a student of medicine at the University of Leyden: his surname was badly Latinised at admission to Pagelius.[26] The University was probably the best of the Netherlands' five provincial universities,[27] and the one most involved in the country's colonial aspirations and international mission: in the quarter century 1626–50 52% of its students came from abroad.[28] It was also active in other areas of Paget's intellectual interest: Joseph Justus Scaliger had established a strong tradition of Semitic studies and the university had acquired an Oriental press, complete with appropriate fonts, in 1625. Paget graduated M.D. on 3 August 1639.[1] His thesis was published under the De Peste (On the Plague).[12] He dedicated it to various Puritans of Cheshire and Shropshire and in it described himself as Mancestr. Anglus.,[29] a Mancunian and Englishman.

Making of a reputation

The Civil War

Nathan Paget moved back to England just as the period of absolute monarchy closed. He was admitted an extra licentiate of the College of Physicians of London on 4 April 1640,[30][31] allowing him to practise in England, outside London. Almost certainly supportive of the Parliamentarian cause,[12] he probably took care to remain in areas with similar political sympathies. His Leyden degree of M.D. was incorporated at the Puritan University of Cambridge on 3 June 1642,[1] just before the outbreak of full-scale hostilities in the English Civil War.

In 1643 Paget took up residence in London at Coleman Street, a noted centre of political and religious radicalism where the Five Members had taken refuge the previous year.[32] He was now settled enough to marry Elizabeth Cromwell.[12] She was a cousin of Oliver Cromwell, the future Lord Protector, although he was still a relatively minor figure, if an able commander, in the army of the Eastern Association. Paget subscribed to the Solemn League and Covenant at St. Stephen Coleman Street,[12] pledging himself to support a Presbyterian polity under the king. However, he was a parishioner of John Goodwin, whose works he owned.[33] Goodwin was an Independent and a radical whose preaching went far beyond the Presbyterian mainstream, and his more conservative parishioners got him sequestered in 1645.[32]

Paget became a Candidate of the College of Physicians on 17 October 1643 and was elected a Fellow on 4 November 1646.[31] Six months later he presented the College with a copy of the works of Francis Bacon,[12] the most important 17th century philosopher of science, signalling a commitment to his empirical method.

Success and preferment

Over the next three years, Paget's political connections became crucial. Most importantly, his wife's cousin Oliver emerged as a leader of the increasingly dominant Independent faction in the New Model Army. Moreover, his father, Thomas Paget had become a "a magisterial figure in Shrewsbury,"[34] where he had taken up the incumbency of Chad's Church. In this important garrison town he preached and wrote powerfully in favour of the regicide, making him a key regional ally of Oliver Cromwell and taking him well-outside the Presbyterian mainstream, in which he had previously been conspicuous. After the king's execution, Thomas issued a pamphlet, entitled A Religious Scrutiny, in which he asserted the religious necessity of the "capital punishment of the polluting and crying sin of wilful murder"[35] – a sin of which he considered the king guilty. Nathan Paget was thus well-connected in the new republican regime, which offered significant patronage to him. On 31 December 1649 he was nominated physician to the Tower of London by the Council of State of the Commonwealth of England.[36] This was confirmed on 5 February 1650.[37]

Around 1645 Paget had been one of the seven physicians associated with Caius College, Cambridge who began to exchange notes on rickets.[38] This seems to have been a response to the inaugural lecture of Daniel Whistler at Leyden University, entitled De morbo puerili Anglorum.[39] George Bate and Assuerus Regimorter were given responsibility for arranging publication of their work. The original intention was to publish a collection of papers. However, Francis Glisson emerged as the best writer in the group, as the others conceded:

- But when Dr Glisson in the judgment of the rest had accuratly interweaved his part (which comprehended the finding out of the Essence of this Diseas) and in that had propounded many things different from the common Opinion of Physitians (though perhaps the less different from the truth) we altered our Resolution, and committed the first Stuff of the whol Work to be woven by him alone, lest at length the parts should arise deformed, mishapen and heterogeneous to themselvs [sic].[40]

As a result, Tractatus de Rachitide Sive Morbo Puerilii was published in Latin in 1650. An English translation appearing the following year, under the title A Treatise of the Rickets: Being a Diseas common to Children.[41] Glisson ensured that all the contributors were credited, with Paget's name appearing on the list.[42] While the language and overall framework of the investigation were in the Galenist idiom of their time, the consideration was very full and included a chapter of Anotomical Observations collected from the Dissection and Inspection of Bodies subdued and killed by this Disease.[43] A full symptomology was established, stressing the thickening of the ends of long bones and the deforming of legs and chest, providing a lasting contribution to the identification and study of the disease.[44]

On 3 May 1655 Paget was elected for the first time to the prestigious post of Censor of the College of Physicians, responsible for policing its monopoly of medical practice and accreditation. He replaced the distinguished and recently deceased Christopher Bennet.[45] He was re-elected to the post in 1657 and 1659.

Contacts and networks

Paget remained connected with wide networks of savants, both within his professional life and in his wider interests in science, politics and culture.

The working group on rickets was closely knit in experience and interests. It seems to have been inspired by the inaugural lecture of Daniel Whistler at Leyden University, entitled De morbo puerili Anglorum.[39] Of the two charged with publication, Regimorter was another Leyden alumnus, whose life and career were oddly symmetrical with Paget's: a near exact contemporary and the son of a Dutch Reformed Church pastor in London, he seems, like Paget, to have gone to Leyden to avoid the Laudian clampdown on Calvinists.[46] Bate became the Cromwell family physician, although he later tried to curry favour with Charles II by claiming to have poisoned the Protector.[47] Another contributor, Jonathan Goddard, also attended Oliver Cromwell and accompanied his expeditions to Ireland and Scotland as army physician.[48]

Early in 1651, the year after publication of De Rachitide, Paget is known to have corresponded with Samuel Hartlib[49] On 7 December he lent manuscripts on alchemy to Elias Ashmole, who was at that time working on his most important compilation, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum.[50]

Paget was a friend of John Milton, whose third wife Elizabeth Minshull was his cousin, once removed.[51] They met through Paget.[52] Around the same period, in 1662, he also found, as reader for the blind Milton, Thomas Ellwood, who reported his first meeting with the poet:[53]

- He received me courteously as well for the sake of Dr. Paget, who introduced me, as of Isaac Pennington, who recommended me; to both of whom he bore a great respect.[54]

Pennington was a notable early Quaker and evidently an associate of Paget: he employed Ellwood as a tutor to his own children, at least once disrupting Milton's progress.[55] The earliest biography of Milton is anonymous: Paget has been suggested as the author.[56]

Paget's library was celebrated, and contained over 2,000 titles. It contained Milton's own works, both prose and poetry, a large collection of pamphlet literature from the period, including many publications relating to the Quakers, and a collection of the works of Fausto Sozzini (Socinus),[57] who initiated an important strain of Nontrinitarianism in Protestantism. According to Christopher Hill

| “ | Nathan Paget must have been a man congenial to Milton in many ways. His literary taste seems to have been Spenserian; he was at least strongly interested in anti-Trinitarianism and mortalism; he may have been one of the Socinian Baptists to whom Sewel refers in 1674. His very special interest in Boehme, whom he appears to have read in the original German (he had several German dictionaries) makes it likely that he would have discussed him with the poet.[58] | ” |

The circle around Milton, Council of State’s Latin Secretary, included polyglots already known to the Pagets. One was John Dury, whose wife, Dorothy, corresponded in Hebrew with Anna Maria van Schurman of Utrecht. Richard Heath, a polyglot associate of Milton, probably found a post through Nathan Paget. On 23 June 1651 he was appointed minister of Alkmund's Church in Shrewsbury, on the recommendation of Milton and Humphrey Mackworth, the governor of Shrewsbury and a parishioner of Nathan's father.[59] The previous minister, Thomas Blake, had been driven out because of his refusal to subscribe to the Engagement, which Thomas Paget had actively promoted.[60] Thus provided for, Heath went on to work on the London Polyglot, a major Biblical production of the Protectorate.

Later life and career

Thomas Paget died in October 1660.[61] His will, proved on 16 October, divided his property between his two surviving sons, Nathan and Thomas, but mentions also three surviving daughters, Dorothy, Elizabeth and Mary. Paget nominated as supervisor of the will Thomas Minshull, an apothecary of Manchester, who was Nathan's cousin and uncle of Elizabeth Milton.[51]

Like most scientists who established themselves during the Protectorate, Nathan Paget does not seem to have suffered any major setback in his career at the Restoration. At this time Sir Edward Alston, an immensely rich Presbyterian society doctor, was keeping the College of Physicians afloat with his money and financial acumen.[62] On 20 September 1663 Paget was designated Harveian lecturer for the following year:[12] an appointment requiring approval by Alston, as well as two senior censors and two senior Elects of the Society.[63] The lecture was a fairly new institution at the time, established by William Harvey himself in a trust dated 26 June 1656. However, it was already an important social as well as academic occasion. The royalist John Evelyn reported in his famous diary attending Paget's lecture on 6 October 1664.[64]

- I heard the anniversary oration in praise of Dr. Harvey, in the Anatomy Theatre in the College of Physicians; after which I was invited by Dr. Alston, the President, to a magnificent feast.[65]

Paget's lecture itself seems to have disappeared but, to meet Harvey's terms, it must have been delivered in Latin and included "an exhortation to the Fellows and Members to search and study out the secrets of Nature by way of experiment."[63]

Paget was named an Elect of the College of Physicians on 8 May 1668.[45] He was also elected Censor again in 1669 and 1678.

Marriage and family

Nathan Paget married Elizabeth Cromwell around 1643. She was the daughter of Philip Cromwell, the son of Sir Henry Cromwell. His eldest son and heir was Sir Oliver Cromwell, who became an important Huntingdonshire landowner, although financially embarrassed because of his father's extravagance.[66] Sir Henry made some provision also for his younger sons. He settled on Robert, his second son, the old Augustinian Friary in Huntingdon, which Robert demolished to build Cromwell House, the birthplace of Oliver Cromwell, the future Lord Protector. Philip, a younger son, lived in Ramsey at a house called the Biggin, a former grange of Ramsey Abbey.[67] His daughter Elizabeth was thus a first cousin of Oliver Cromwell, although there was no reason to suspect his future importance when she married Nathan Paget. Elizabeth Cromwell was probably about the same age as Nathan Paget and certainly predeceased him, as she is not mentioned in his will. No children of the marriage are known.

Family tree

Death

Nathan Paget died in January 1679 at his home in Coleman Street.[12] His will was dated 7 January and it was proved on 15 January.[29] He left his house to his half-brother, Thomas Paget, who was a minister. There were also bequests for his cousins once removed, John Goldsmith, a Middle Temple lawyer, who was also appointed executor, and Elizabeth Milton, as well as money for the poor of the parish. To the College of Physicians he left the revenues from some properties he had leased in Petty France in the Little Moorfields area of London. These amounted to £20 per annum for more than thirty years.[45]

Paget's famous library was sold off by William Cooper, an auctioneer of books who specialised in the occult sciences.[68] A full catalogue was published in 1681, under the title: Bibliotheca medica, viri clarissimi Nathanis Paget, M.D., cui adjiciuntur quamplurimi alii libri theologici, philosophici, &c.; quorum omnium auctio habebitur Londini, ad insigne Pelicani in vico vulgo dicto Little-Britain 24 die Octobris1681.

Nathan Paget's life in maps

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Paget, Nathan (PGT641N)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge., also at Venn, John; Venn, J.A., eds. (1924). "Paget, Nathan". Alumni Cantabrigienses (Part 1). 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 295 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Sprunger, Keith L. "Paget, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21117. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Booker, p. 2.

- ↑ Booker, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Sprunger, Keith L. "Paget, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21114. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Hall, p. 479

- ↑ Cf. Minshull Pedigree in Hall, p. 476-7

- ↑ Hall, p. 416

- ↑ Hall, p. 295

- ↑ Hall, p. 296

- ↑ Halley, p. 130-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Elmer, Peter. "Paget, Nathan". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21117. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Halley, p. 132

- ↑ Hall, p. 279.

- ↑ Urwick, p. xi-xii.

- ↑ Urwick, p. 370.

- ↑ Halley, p. 133

- ↑ Preface to Meditations of death (1639), quoted in Hall, p. 295.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 144.

- ↑ Miller, Some Inferences from Milton's Hebrew: Abstract

- ↑ Hartlib Papers, Ref: 5/52/1A-2B: 1B, 2A BLANK.

- ↑ Hartlib Papers, Ref: 11/1/117A-B

- ↑ Aughterson, Kate. "Paget, Briget". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68076. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Urwick, p. ix.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 78-80.

- ↑ Peacock, p. 75.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 176.

- ↑ Boxer, p. 177.

- 1 2 Booker, p. 67.

- ↑ Moore, Norman (1895). "Paget, Nathan". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography. 43. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 59.

- 1 2 Physicians and Irregular Medical Practitioners in London 1550-1640 Database: College membership.

- 1 2 Liu, Tai. "Goodwin, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10994. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ John Coffey. John Goodwin and the Puritan Revolution (2008), p. 281.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 106.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 110.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1649–1650, 31 December 1649, p. 460.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1649–1650, 5 February 1650, p. 506.

- ↑ Hochberg, p. 7.

- 1 2 Williamson, p. 43.

- ↑ Glisson, Preface to the Reader.

- ↑ Glisson, Title Page.

- ↑ Glisson, List of Contributors.

- ↑ Glisson, p. 9-16.

- ↑ Williamson, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 Munk, p. 243.

- ↑ Birken, William. "Regemorter, Assuerus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23313. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Munk, p. 229.

- ↑ Munk, p. 241.

- ↑ Hartlib Papers, Ref: 28/2/1A-12A: 1B BLANK

- ↑ Burman, The Life of Elias Ashmole Esq., p. 315.

- 1 2 Hall, p. 477.

- ↑ Hunter and Shawcross, p. 173.

- ↑ William Bridges Hunter et al., A Milton Encyclopedia vol. 7 (1980), p. 97.

- ↑ Hanford, p. 169.

- ↑ Hanford, p. 170.

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Hanford, p. 240.

- ↑ Christopher Hill, Milton and the English Revolution (1979), Appendix 3, Nathan Paget and his Library, p. 495.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 116.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 114-5.

- ↑ Urwick, p. 482.

- ↑ Birken, William. "Alston, Sir Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/426. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 Bishop and Poynter, p. 622.

- ↑ Bishop and Poynter, p. 623.

- ↑ Diary of John Evelyn, p. 275.

- ↑ Page et al, A History of the County of Huntingdon, Volume 2, The borough of Huntingdon: Introduction, castle and borough.

- ↑ Page et al, A History of the County of Huntingdon, Volume 2, Parishes: Ramsey.

- ↑ Linden, Stanton J. "Cooper, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53668. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

References

- Aughterson, Kate. "Paget, Briget". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68076. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Birken, William. "Alston, Sir Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/426. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Birken, William. "Regemorter, Assuerus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23313. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Bishop, W. J.; Poynter, F. N. L. (18 October 1947). "The Harveian Orations 1656–1947: a Study in Tradition" (PDF). British Medical Journal. British Medical Association. 2: 622–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4528.622. PMC 2055934

. PMID 20268483. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

. PMID 20268483. Retrieved 11 August 2015. - Booker, John (1854). A History of the Ancient Chapel of Blackley, in Manchester Parish. Manchester: George Simms. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph (1965). The Dutch Seaborne Empire 1600–1800). London: Penguin. ISBN 0140136185.

- Burman, Charles (1774). The Lives of those Eminent Antiquaries Elias Ashmole, Esquire, and Mr. William Lilly. London: T. Davies. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Coffey, John (2008). John Goodwin and the Puritan Revolution: Religion and Intellectual Change in Seventeenth-Century England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843834281.

- Coulton, Barbara (2010). Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400-1700. Little Logaston: Logaston Press. ISBN 978 1 906663 47 6.

- Elmer, Peter. "Paget, Nathan". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21117. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Evelyn, John (1818). Bray, William, ed. The diary of John Evelyn. 1 (1901 ed.). London and New York: Dunne. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Green, Mary Anne Everett, ed. (1875). Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1649–1650. London: Longman. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Glisson, Francis (1651). "A Treatise of the Rickets, being a disease common to children". Early English Books Text Creation Partnership. Ann Arbor, MI ; Oxford (UK): Text Creation Partnership. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Greengrass, M.; Leslie, M.; Hannon, M., eds. (2013). "The Hartlib Papers". HRI Online. HRI Online Publications. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Hall, James (1883). A History of the Town and Parish of Nantwich, or Wich-Malbank, in the County Palatine of Chester. Nantwich. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Halley, Robert (1872). Lancashire, its Puritanism and Nonconformity (2 ed.). Manchester: Tubbs and Brook. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Hanford, James Holly (1949). John Milton, Englishman. New York: Crown Publishers. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- Hill, Christopher (1977). Milton and the English Revolution (1979 ed.). London: Viking. ISBN 9780571111701.

- Hochberg, Ze’ev (2003). "Rickets – Past and Present" (PDF). Karger. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Hunter, William Bridges; Shawcross, John T. (1978). A Milton Encyclopedia. Manchester: Bucknell University Press. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Linden, Stanton J. "Cooper, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53668. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Miller, Leo (1984). "Some Inferences from Milton's Hebrew". Milton Quarterly. 18 (2): 41–46. doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1984.tb00279.x. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Paget, Nathan". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Paget, Nathan". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - Munk, William (1878). The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London. 1. London: Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Page, William; Proby, Granville; Inskip Ladds, S., eds. (1932). A History of the County of Huntingdon. 2. London: Institute of Historical Research and the History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Paget, John (1641). Paget, Thomas; Paget, Robert, eds. A Defence Of Church-Government, Exercised in Presbyteriall, Classicall, & Synodall Assemblies. London: Thomas Underhill. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- Pelling, Margaret; White, Frances (2004). "Physicians and Irregular Medical Practitioners in London 1550-1640 Database". British History Online. Institute of Historical Research and the History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Peacock, Edward, ed. (1883). Index to English Speaking Students who have Graduated at Leyden University. Hertford: Stephen Austin. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Sprunger, Keith L. "Paget, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21114. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Sprunger, Keith L. "Paget, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21117. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Liu, Tai. "Goodwin, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10994. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Urwick, William, ed. (1864). Historical Sketches of Nonconformity in the County Palatine of Chester. London and Manchester: Kent and Co. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- "Paget, Nathan (PGT641N)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge., also at Venn, John; Venn, J.A., eds. (1924). "Paget, Nathan". Alumni Cantabrigienses (Part 1). 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 295 – via Internet Archive.

- Williamson, R. T. (1923). English Physicians of the Past. 1. Newcastle upon Tyne: Andrew Reid & Company. Retrieved 5 August 2015.