Mucus

In vertebrates, mucus (/mjuːkəs/ MYOO-kəss; adjectival form: "mucous") is a slippery secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. Mucous fluid is rich in glycoproteins and water and is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands. Mucous fluid may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is a viscous colloid containing antiseptic enzymes (such as lysozymes), immunoglobulins, inorganic salts, proteins such as lactoferrin,[1] and glycoproteins known as mucins that are produced by goblet cells in the mucous membranes and submucosal glands. This mucus serves to protect epithelial cells (that line the tubes) in the respiratory, gastrointestinal, urogenital, visual, and auditory systems; the epidermis in amphibians; and the gills in fish. A major function of this mucus is to protect against infectious agents such as fungi, bacteria and viruses. The average human nose produces about a liter of mucus per day.[2] Most of the mucus produced is in the gastrointestinal tract.

Bony fish, hagfish, snails, slugs, and some other invertebrates also produce external mucus. In addition to serving a protective function against infectious agents, such mucus provides protection against toxins produced by predators, can facilitate movement and may play a role in communication.

The rest of this article deals with the production and function of mucus in humans.

Respiratory system

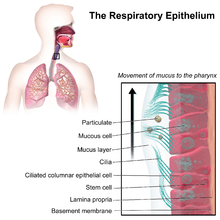

In the human respiratory system, mucus aids in the protection of the lungs by trapping foreign particles that enter them, in particular, through the nose, during normal breathing. "Phlegm" is a specialized term for mucus that is restricted to the respiratory tract, whereas the term "nasal mucus" describes secretions of the nasal passages.

Nasal mucus is produced by the nasal mucosa; and mucosal tissues lining the airways (trachea, bronchus, bronchioles) is produced by specialized airway epithelial cells (goblet cells) and submucosal glands. Small particles such as dust, particulate pollutants, and allergens, as well as infectious agents and bacteria are caught in the viscous nasal or airway mucus and prevented from entering the system. This event along with the continual movement of the respiratory mucus layer toward the oropharynx, helps prevent foreign objects from entering the lungs during breathing. This explains why coughing often occurs in those who smoke cigarettes. The body's natural reaction is to increase mucus production. In addition, mucus aids in moisturizing the inhaled air and prevents tissues such as the nasal and airway epithelia from drying out.[3] Nasal and airway mucus is produced continuously, with most of it swallowed subconsciously, even when it is dried.[4]

Increased mucus production in the respiratory tract is a symptom of many common illnesses, such as the common cold and influenza. Hypersecretion of mucus can occur in inflammatory respiratory diseases such as respiratory allergies, asthma, and chronic bronchitis.[3] The presence of mucus in the nose and throat is normal, but increased quantities can impede comfortable breathing and must be cleared by blowing the nose or expectorating phlegm from the throat.

Diseases involving mucus

In general, nasal mucus is clear and thin, serving to filter air during inhalation. During times of infection, mucus can change color to yellow or green either as a result of trapped bacteria[5] or due to the body's reaction to viral infection.[6] The green color of mucus comes from the heme group in the iron-containing enzyme myeloperoxidase secreted by white blood cells as a cytotoxic defense during a respiratory burst.

In the case of bacterial infection, the bacterium becomes trapped in already-clogged sinuses, breeding in the moist, nutrient-rich environment. Sinusitis is an uncomfortable condition which may include congestion of mucus. A bacterial infection in sinusitis will cause discolored mucus and would respond to antibiotic treatment; viral infections typically resolve without treatment.[7] Almost all sinusitis infections are viral and antibiotics are ineffective and not recommended for treating typical cases.[8]

In the case of a viral infection such as cold or flu, the first stage and also the last stage of the infection cause the production of a clear, thin mucus in the nose or back of the throat. As the body begins to react to the virus (generally one to three days), mucus thickens and may turn yellow or green. Viral infections cannot be treated with antibiotics, and are a major avenue for their misuse. Treatment is generally symptom-based; often it is sufficient to allow the immune system to fight off the virus over time.[9]

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disease that affects the entire body. Symptoms begin mostly in the lungs, with viscous (thick) mucus that is difficult to expel.

Mucus as a medical symptom

Increased mucus production in the upper respiratory tract is a symptom of many common ailments, such as the common cold. Nasal mucus may be removed by blowing the nose or by using nasal irrigation. Excess nasal mucus, as with a cold or allergies, due to vascular engorgement associated with vasodilation and increased capillary permeability caused by histamines,[10] may be treated cautiously with decongestant medications. Excess mucus production in the bronchi and bronchioles, as may occur in asthma, bronchitis or influenza, may be treated with anti-inflammatory medications as a means of reducing the airway inflammation, which triggers mucus over-production. Thickening of mucus as a "rebound" effect following overuse of decongestants may produce nasal or sinus drainage problems and circumstances that promote infection.

Cold weather and nasal mucus

During exposure to cold weather, the cilia, which normally sweep mucus away from the nostrils and toward the back of the throat (see respiratory epithelium), become sluggish or completely cease functioning. This results in mucus running down the nose and dripping (a runny nose). Mucus also thickens in cold weather; when an individual comes in from the cold, the mucus thaws and begins to run before the cilia begin to work again.

Digestive system

In the human digestive system, mucus is used as a lubricant for materials that must pass over membranes, e.g., food passing down the esophagus. Mucus is extremely important in the intestinal tract. It forms an essential layer in the colon and in the small intestine that helps reduce intestinal inflammation by decreasing bacterial interaction with intestinal epithelial cells.[11] A layer of mucus along the inner walls of the stomach is vital to protect the cell linings of that organ from the highly acidic environment within it.[scientific 1] Mucus is not digested in the intestinal tract. Mucus is also secreted from glands within the rectum due to stimulation of the mucous membrane within.

Reproductive system

In the human female reproductive system, cervical mucus prevents infection. The consistency of cervical mucus varies depending on the stage of a woman's menstrual cycle. At ovulation cervical mucus is clear, runny, and conducive to sperm; post-ovulation, mucus becomes thicker and is more likely to block sperm. Several Fertility Awareness methods, such as the Creighton Model and Billings method rely on this fact to prevent or to improve the odds of pregnancy.

In the human male reproductive system, the seminal vesicles contribute up to 100% of the total volume of the semen and contain mucus, amino acids, prostaglandins, vitamin C, and fructose as the main energy source for the sperm.

See also

- Alkaline mucus

- Dried nasal mucus

- Empty nose syndrome

- Mucoadhesion

- Mucophagy

- Snail slime

- Sniffle

- Spinnbarkeit

Notes

- ↑ Purves, William. "Why don't our digestive acids corrode our stomach linings?". Scientific American. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

Second, HCl in the lumen doesn't digest the mucosa because goblet cells in the mucosa secrete large quantities of protective mucus that line the mucosal surface.

References

- ↑ Singh, PK; Parsek, MR; Greenberg, EP; Welsh, MJ (May 2002). "A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development". Nature. 417 (6888): 552–5. doi:10.1038/417552a. PMID 12037568.

- ↑ "What's a Booger?". KidsHealth.

- 1 2 Thorton, DJ; Rousseau, K; MucGuckin, MA (2008). "Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus". Annual Review of Physiology. 70 (44): 459–486. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. PMID 17850213.

- ↑ Gates, Stefan (2006). "Boogers". Gastronaut: Adventures in Food for the Romantic, the Foolhardy, and the Brave. pp. 68, 69. ISBN 0-15-603097-7.

- ↑ "Runny Nose (with green or yellow mucus)". Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 9, 2006. Archived from the original on Mar 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Yellow-green Phlegm and Other Myths". University of Arizona campus health services. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Consumer Reports; American Academy of Family Physicians (April 2012), "Treating sinusitis: Don't rush to antibiotics" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, Consumer Reports, retrieved August 17, 2012

- ↑ American Academy of Family Physicians, presented by ABIM Foundation, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF), Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Academy of Family Physicians, retrieved August 14, 2012

- ↑ "Definition of Viral Infection". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- ↑ Monroe EW, Daly AF, Shalhoub RF (February 1997). "Appraisal of the validity of histamine-induced wheal and flare to predict the clinical efficacy of antihistamines". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 99 (2): S798–806. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70128-3. PMID 9042073.

- ↑ Johansson, Malin E. V.; Gustafsson, Jenny K.; Sjöberg, Karolina E.; Petersson, Joel; Holm, Lena; Sjövall, Henrik; Hansson, Gunnar C. (2010-01-01). "Bacteria penetrate the inner mucus layer before inflammation in the dextran sulfate colitis model". PloS One. 5 (8): e12238. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012238. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2923597

. PMID 20805871.

. PMID 20805871.