ArtScroll

| |

| Parent company | Mesorah Publications |

|---|---|

| Status | Active |

| Founded | 1976 |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Headquarters location | Brooklyn, New York |

| Key people | Nosson Scherman and Meir Zlotowitz, general editors |

| Official website | www.artscroll.com |

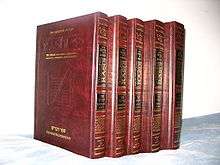

ArtScroll is an imprint of translations, books and commentaries from an Orthodox Jewish perspective published by Mesorah Publications, Ltd., a publishing company based in Brooklyn, New York. Its general editors are Rabbis Nosson Scherman and Meir Zlotowitz.

History

In 1975,[1] Zlotowitz, a graduate of Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, was director of a high-end graphics studio in New York.[2] The firm, named ArtScroll Studios,[1] produced brochures,[3] invitations, awards and ketubahs.[1] Rabbi Nosson Scherman, then principal of Yeshiva Karlin Stolin Boro Park,[1] was recommended to Zlotowitz as someone who could write copy, and they collaborated on a few projects.[4]

In late 1975,[1] a close friend of Zlotowitz, Rabbi Meir Fogel, died in his sleep, prompting Zlotowitz to want to do something to honor his memory. As Purim was a few months away, he decided to write an English translation and commentary on the Book of Esther, and asked Scherman to write the introduction. The book was completed in honor of the shloshim (the 30-day commemoration of a death)[1] and sold out its first edition of 20,000 copies within two months.[5] With the encouragement of Rabbi Moses Feinstein, Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky, and other Gedolei Yisrael, the two continued producing commentaries, beginning with a translation and commentary on the rest of the Five Megillot (Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations and Ruth),[6] and went on to publish translations and commentaries on the Torah, Prophets, Talmud, Passover Haggadah, siddurs and machzors. The name ArtScroll was chosen for the publishing company to emphasize the visual appeal of the books.[7] In its first 25 years, ArtScroll produced more than 700 books, including novels, history books, children's books and secular textbooks,[2] and is now one of the largest publishers of Jewish books in the United States.[3]

ArtScroll is perhaps best identified through the "hallmark features" of its design elements such as typeface and layout, through which "ArtScroll books constitute a field of visual interaction that enables and encourages the reader to navigate the text in particular ways."[8] The emphasis on design and layout can be understood "as a strategy on the part of the publisher to achieve a range of cognitive as well as esthetic effects."[8]

Primary publications

ArtScroll publishes books on a variety of Jewish subjects. The best known is probably an annotated Hebrew-English siddur ("prayerbook") (The ArtScroll Siddur). In recent years its Torah translation and commentary, a series of translations and commentaries on books of the Tanach (Hebrew Bible), and an English translation and elucidation of the Babylonian Talmud have enjoyed great success. Other publications include works on Jewish Law, novels and factual works based on Jewish life or history, and cookbooks.

Popular acceptance

Mesorah Publications received widespread acclaim in response to its ArtScroll line of prayerbooks, starting with The Complete ArtScroll Siddur, Ed. Nosson Scherman, 1984. This work gained wide acceptance in the Orthodox Jewish community, and within a few years became a popular Hebrew-English siddur (prayerbook) in the United States. It offered the reader detailed notes and instructions on most of the prayers and versions of this prayerbook were produced for the High Holidays, and the three pilgrimage festivals Passover, Sukkot and Shavuot.

In 1993 Mesorah Publications published The Chumash: The Stone Edition, a translation and commentary on the Chumash arranged for liturgical use and sponsored by Irving I. Stone of American Greetings, Cleveland, Ohio. It has since become a widely available English-Hebrew Torah translation and commentary in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries.

While many Conservative synagogues rely on the Siddur Sim Shalom or Or Hadash prayer books and Etz Hayim Humash, "a small but growing number of North American Conservative Jewish congregations ... have recently adopted ArtScroll prayer books and Bibles as their 'official' liturgical texts, not to mention a much larger number of Conservative synagogues that over recent years have grown accustomed to individual congregants participating in prayer services with editions of ArtScroll prayer books in their hands."[9] The shift has mainly occurred among more traditionally minded Conservative congregants and rabbis (sometimes labeled "Conservadox") "as an adequate representation of the more traditional liturgy they seek to embrace."[9]

Since the advent of ArtScroll, a number of Jewish publishers have printed books and siddurim with similar typefaces and commentary, but with a different commentary and translation philosophy.

Kosher By Design

In 2003 ArtScroll published a cookbook by Susie Fishbein entitled Kosher By Design: Picture-perfect food for the holidays & every day. The cookbook contains both traditional recipes and updated versions of traditional recipes.[10] All the recipes are kosher and the book puts an emphasis on its food photography.[3][11] Since publication the book has sold over 400,000 copies from 2003 through 2010[12][13] and Fishbein has become a media personality, earning the sobriquets of "the Jewish Martha Stewart" and the "kosher diva".[10] ArtScroll has realized the books' salability by extending beyond its traditional Orthodox Jewish market into the mainstream market, including sales on Amazon, at Barnes & Noble[14] and Christian evangelical booksellers,[10] in Williams-Sonoma stores, and in supermarkets.[14]

Editorial policy

Works published by Mesorah under this imprint adhere to a perspective appealing to many Orthodox Jews, but especially to Orthodox Jews who have come from less religious backgrounds, but are returning to the faith (Baalei Teshuva). Due to the makeup of the Jewish community in the USA, most of the prayer books are geared to the Ashkenazic custom. In more recent years, Artscroll has collaborated with Sephardic community leaders in an attempt to bridge this gap. Examples of this include a Sephardic Haggadah published by Artscroll, written by Sephardic Rabbi Eli Mansour, and the book Aleppo, about a prominent Sephardic community in Syria.

In translations and commentaries, ArtScroll accepts midrashic accounts in a historical fashion, and at times literally, and generally disregards (and occasionally disagrees with) textual criticism.

Schottenstein Edition Talmud

Mesorah has a line of Mishnah translations and commentaries, and a line of Babylonian Talmud translations and commentaries, The Schottenstein Edition of The Talmud Bavli ("Babylonian Talmud"). The set of Talmud was completed in late 2004, giving a 73 volume English edition of the entire Talmud. This was the second complete translation of the Talmud into English (the other being the Soncino Talmud published in the United Kingdom during the mid-twentieth century).

The first volume, Tractate Makkos, was published in 1990, and dedicated by Mr. and Mrs. Marcos Katz. Jerome Schottenstein was introduced by Dr. Norman Lamm to the publication committee shortly thereafter. He began by donating funds for the project in memory of his parents Ephraim and Anna Schottenstein one volume at a time, and later decided to back the entire project. When Jerome died, his children and widow, Geraldine, rededicated the project to his memory in addition to those of his parents. The goal of the project was to, "open the doors of the Talmud and welcome its people inside."

The text generally consists of two side-by-side pages: one of the Aramaic/Hebrew Vilna Edition text, and the corresponding page consists of an English translation. The English translation has a bolded literal translation of the Talmud's text, but also includes un-bolded text clarifying the literal translation. (The original Talmud's text is often very unclear, referring to places, times, people, and laws that it does not explain. The un-bolded text attempts to explain these situations. The text of the Talmud also contains few prepositions, articles, etc. The un-bolded text takes the liberty of inserting these parts of speech.) The result is an English text that reads in full sentences with full explanations, while allowing the reader to distinguish between direct translation and a more liberal approach to the translation. (This also results in one page of the Vilna Talmud requiring several pages of English translation.) Below the English translation appear extensive notes including diagrams.

ArtScroll's English explanations and footnoted commentary in the Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud are based on the perspective of classical Jewish sources. The clarifying explanation is generally based on the viewpoint of Rashi, the medieval commentator who wrote the first comprehensive commentary on the Talmud. The Schottenstein Edition does not include contemporary academic or critical scholarship.

The total cost of the project is estimated at US$21 million, most of which was contributed by private donors and foundations. Some volumes have up to 2 million copies in distribution, while more recent volumes have only 90,000 copies currently printed. A completed set was dedicated on February 9, 2005, to the Library of Congress, and the siyum (celebration at the "completion") was held on March 15, 2005, the 13th yahrzeit of Jerome Schottenstein, at the New York Hilton.

Mesorah and the Schottenstein family have also begun a Hebrew version of the commentary and have begun both an English and Hebrew translation of the Talmud Yerushalmi (Jerusalem Talmud).

Transliteration system

Artscroll publications, such as the Stone Editions of Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and Chumash (Pentateuch) use many more transliterated Hebrew words rather than English words, compared to editions such as the Tanakh of the Jewish Publication Society. This reflects a higher use of untranslated Hebrew terminology in Haredi English usage.

ArtScroll's transliteration system for Hebrew transliteration for readers of the English language generally uses Ashkenazi consonants and Sefardi vowels. The two major differences between the way Sefardi and Ashkenazi Hebrew dialects are transcribed are as follows:

- the letter Tav without a dagesh (emphasis point) is transcribed as [t] and [s] respectively

- ArtScroll uses the latter

- the vowel kamatz gadol, is transcribed [a] and [o] respectively

- ArtScroll uses the former

As such you would have the following transliterations:

| Ashkenazi | Sefardi | ArtScroll |

|---|---|---|

| Boruch | Barukh | Baruch |

| Shabbos | Shabbat | Shabbos (ArtScroll makes an exception due to widespread usage) |

| Succos | Succot | Succos |

| Avrohom | Avraham | Avraham |

| Akeidas Yitzchok | Akedat Yitzhak | Akeidas Yitzchak |

Criticism

- A large number of grammatical errors exist in their Bible and commentary translations, changing the meaning of these passages. B. Barry Levy alleged in 1981:

Dikduk (grammar) is anathema in many Jewish circles, but the translation and presentation of texts is, to a large extent, a philological activity and must be philologically accurate. The ArtScroll effort has not achieved a respectable level. There are dozens of cases where prepositions are misunderstood, where verb tenses are not perceived properly and where grammatical or linguistic terms are used incorrectly. Words are often vocalized incorrectly. These observations, it should be stressed, are not limited to the Bible text but refer to the talmudic, midrashic, targumic, medieval and modern works as well. Rabbinical passages are removed from their contexts, presented in fragmentary form thus distorting their contents, emended to update their messages even though these new ideas were not expressed in the texts themselves, misvocalized, and mistranslated: i.e. misrepresented.[15]

- The commentary of Rashbam to the first chapter of Genesis [16] in ArtScroll's Czuker Edition Hebrew Chumash Mikra'os Gedolos Sefer Bereishis (2014) has been censored. The missing passages are related to Rashbam's interpretation of the phrase in Genesis 1:5, “and there was an evening, and there was a morning, one day.” The Talmud[17] cites these words to support the halakhic view that the day begins at sundown. However, Rashbam takes a peshat (plain sense) approach, as he does throughout his commentary, reading the verse as follows: “There was an evening (at the conclusion of daytime) and a morning (at the end of night), one day”; that is, the day begins in the morning and lasts until the next daybreak.[18] In their defense, ArtScroll points out that in standard Mikra'os Gedolos the entire commentary of Rashbam on the beginning of Bereishis is missing. When adding in from older manuscripts, they left out the exegeses to Genesis 1:5 because of questions to its authenticity, particularly those raised by Ibn Ezra in his Iggeres HaShabbos (Letter on Sabbath) who wrote "heretics put it forth".[19]

- In many yeshivas student are discouraged from using the Schottenstein elucidation of the Talmud because it is viewed as a crutch for students who wish to avoid in depth study of the original texts (as ArtScroll warns in the introduction to the work).

Bibliography

- Rabbi B. Barry Levy. "Our Torah, Your Torah and Their Torah: An Evaluation of the ArtScroll phenomenon.". In: "Truth and Compassion: Essays on Religion in Judaism", Ed. H. Joseph et al.. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1983.

- B. Barry Levy. "Judge Not a Book By Its Cover". Tradition 19(1)(Spring 1981): 89-95 and an exchange of letters in Tradition 1982;20:370-375.

- Jacob J. Schachter, "Facing the Truths of History" Torah u-Madda Journal 8 (1998–1999): 200-276 (PDF file).

- Jacob J. Schachter, "Haskalah, Secular Studies, and the close of the Yeshiva in Volozhin in 1892" Torah u-Madda Journal

- Jeremy Stolow, Orthodox by Design: Judaism, Print Politics, and the ArtScroll Revolution

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Resnick, Eliot (6 June 2007). "'Our Goal is to Increase Torah Learning'". The Jewish Press. Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- 1 2 Ephross, Peter (13 July 2001). "In 25 Years of Publishing, Artscroll captures Zeitgeist". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 Berger, Joseph (10 February 2005). "An English Talmud for Daily Readers and Debaters". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ Hoffman, Rabbi Yair (3 December 2009). "The ArtScroll Revolution: 5TJT interviews Rabbi Nosson Scherman". Five Towns Jewish Times. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ Nussbaum Cohen, Debra (11 October 2007). "Feminists Object, But ArtScroll Rolls On". The Jewish Week. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ↑ Zlotowitz, Meir (1986). The Five Megillos: A new translation with overviews and annotations anthologized from the classical commentators. Mesorah Publications Ltd.

- ↑ Eller, Sandy; Shidler, Yosef (17 March 2010). "Brooklyn, NY - VIN Exclusive: Behind The Scenes At Artscroll [video]". VIN. vosizneias.com. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- 1 2 Jeremy Stolow, Orthodox by Design: Judaism, Print Politics, and the ArtScroll Revolution (2010), p. 157

- 1 2 Jeremy Stolow, Orthodox by Design: Judaism, Print Politics, and the ArtScroll Revolution (2010), at p. 75 (available at https://books.google.com/books?id=MO159He5WgYC&pg=PA75&lpg=PA75&dq=conservative+judaism+artscroll&source=bl&ots=HTZuO1NEZ3&sig=cV558RPKXCgU7SEhYc6OfREGVlU&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9j7nUZydGYrEiwK0-oCwBQ&ved=0CFMQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=conservative%20judaism%20artscroll&f=false).

- 1 2 3 Stolow, Jeremy (28 April 2010). Orthodox By Design: Judaism, print politics, and the ArtScroll revolution. University of California Press. pp. 120–130. ISBN 0-520-26426-6.

- ↑ Church & Synagogue Libraries, Volumes 38-39. Church and Synagogue Library Association. 2005.

- ↑ Moskin, Julia (16 April 2008). "One Cook, Thousands of Seders". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Chefitz, Michael (15 November 2010). "Kosher by Design's Susie Fishbein is Back!". TribLocal Skokie. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- 1 2 Sanders, Gavriel Aryeh (14 March 2005). "Kosher Diva Outdoes Herself With Latest Offering". Jewish World Review. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Levy, B. Barry (Spring 1981). "Judge Not a Book By Its Cover". Tradition. 19 (1): 89–95.

- ↑ ArtScroll omitted entire sections of Rashbam's commentary on Gen. 1:4, 1:5, 1:8, and 1:31. See David Rosin, Perush Rashbam al Ha-Torah (Breslau, 1882), pp. 5-6, 9 Archived February 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hulin 83a

- ↑ First identified by Marc B. Shapiro on Seforim Blog. See also David S. Zinberg, "An inconvenient text," The Jewish Standard (February 12, 2015)

- ↑ Shapiro, Marc B. "ArtScroll's Response and My Comments". the Seforim Blog. the Seforim Blog. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

External links

- Company website

- Jewish Press Interview with Nosson Scherman

- Jeremy Stolow (2006), ArtScroll, Encyclopaedia Judaica; via Jewish Virtual Library

- Critical evaluations of Artscroll