Max Fleischer

| Max Fleischer | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

July 19, 1883 Krakow, Austria-Hungary |

| Died |

September 11, 1972 (aged 89) Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Occupation | Animator, inventor, film director, film producer |

| Years active | 1918–1962 |

| Religion | Agnostic |

| Spouse(s) | Essie Goldstein |

Max Fleischer (July 19, 1883 – September 11, 1972) was an American animator, inventor, film director and producer.[1][2]

Fleischer was a pioneer in the development of the animated cartoon and served as the head of Fleischer Studios. He brought such animated characters as Koko the Clown, Betty Boop, Popeye, and Superman to the movie screen and was responsible for a number of technological innovations including the Rotoscope.,[3] the "Bouncing Ball" Song Films, and "The Stereoptical Process."

Early life

Born to a Jewish family in Kraków,[4] then part of the Austrian-Hungarian province of Galicia, Max Fleischer was the second of six children of an Austrian immigrant tailor, William Fleischer.[5] His family emigrated to the USA in 1887, settling in New York City, where he attended public school. During his early formative years he enjoyed a Middle Class life style the result of his father's success as an exclusive tailor to high society clients. This changed drastically after his father lost his business ten years later. His teens were spent in Brownsville, a poor Jewish ghetto in Brooklyn. Motivated to succeed, he continued his education, attending Evening High School. He received Commercial Art training at Cooper Union and formal art instruction at the Art Students League of New York, studying under the famous George Bridgman. He also attended The Mechanics and Tradesman's School in midtown Manhattan.

Fleischer began his career at The Brooklyn Daily Eagle first as an Errand Boy, and was advanced to Photographer, Photoengraver, and later, became a staff Cartoonist. At first he drew single panel editorial cartoons, then graduated to the full strips, "Little Algie," and "S.K. Sposher, the Camera Fiend." These satirical strips reflected his life in Brownsville and his fascination with technology and photography respectively-both displaying his sense of irony and fatalism. It was during this period he met newspaper cartoonist and early animator, John Randolph Bray, who would later give him his start in the animation field.

On December 25, 1905, Fleischer married his childhood sweetheart, Ethel (Essie) Goldstein. On the recommendation of Bray, Fleischer was hired as a Technical Illustrator for The Electro-Light Engraving Company in Boston. In 1909 he moved to Syracuse, New York, working as a catalog illustrator for the Crouse-Hinds Company, and a year later returned to New York as Art Editor for Popular Science Magazine under Editor Waldemar Klaempffert.

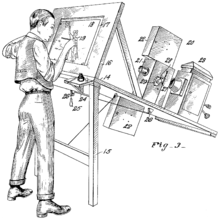

The Rotoscope

By 1914 the first commercially produced animated cartoons started to appear in movie theaters. But they tended to be stiff and jerky. Fleischer devised an improvement in animation through a combined projector and easel for tracing images from live action film. This device, known as a rotoscope, enabled Flesicher to produce the first realistic animation since the initial works of Winsor McCay.[6] Although his patent was granted in 1917, Max and his brothers Joe and Dave Fleischer made their first series of tests between 1914 and 1916.

First Venture

The Pathe Film exchange offered Max his first opportunity as a Producer due in part to the fact that Dave had been working there as a Film Cutter since 1914. Max chose a political satire of a hunting trip by Theodore Roosevelt. After several months of labor, the film was rejected, and Max was making the rounds again when he was reunited with John R. Bray in an outer office at Paramount. Bray had a distribution contract with Paramount at the time, and hired Max as Production Supervisor for his studio. With the outbreak of World War I, Max was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to produce the first Army Training films on subjects that included "Contour Map Reading," "Operating the Stokes Mortar," and "Firing the Lewis Machine Gun," and "Submarine Mine Laying." Following the Armistice, Fleischer returned to Bray and the production of theatrical and educational films.

The Inkwell Studios

Fleischer produced his Out of the Inkwell films featuring "The Clown" character, which originated from his youngest brother Dave, who had worked as a Sideshow clown at Coney Island. And it was the one of the later test made of from footage of Dave as a clown that interested Bray.

Fleischer's initial series was first produced at The Bray Studios (see Bray Productions) and released as a monthly installment in the Bray-Goldwyn Pictograph Screen Magazine from 1919 to 1921. In addition to producing "Out of the Inkwell," Max's position at Bray was primarily Production Manager, and Supervisor of a number of educational and technical films such as "The Electric Bell," "All Aboard for the Moon," and "Hello, Mars." And it was as Production Manager that Fleischer hired his first Animator, Roland Crandall, who remained with him throughout the active years of Fleischer's studio.

"Out of the Inkwell" featured the novelty of combining live action and animation and served as semi-documentaries with the appearance of Max Fleischer as the artist who dipped his pen into the ink bottle to produce the clown figure on his drawing board. While the technique of combining animation with live action was already established by others at The Bray Studio, it was Fleischer's clever use of it combined with Fleischer's realistic animation that made his series unique.

In 1921, Max and Dave established Out of the Inkwell Films, Incorporated and continued production of "Out of the Inkwell" through various States Rights Distributors. "The Clown" had no name until 1924, when Dick Huemer came aboard after animating on the early "Mutt and Jeff" cartoons. He set the style for the series, redesigning "The Clown," and named him "Ko-Ko." Huemer created Ko-Ko's canine companion known as Fitz, and moved the Fleischer's away from their dependency on the Rotoscope for fluid animation, leaving it for special uses and reference points where compositing was involved. And because Max valued Huemer's work that he instructed Huemer to make just the key poses and have an assistant fill in the remaining drawings. Max assigned Art Davis as Huemer's assistant and this was the beginning of the position of "Inbetweener," which was essentially another Fleischer "invention" that resulted in efficient production and was adopted by the entire industry by the 1930s.

It was during this time that Max developed "The Rotograph," a means of photographing live action film footage with animation cels for a composited image. This was an improvement over the method used by Bray where a series of 8" x 10" stills were made from motion picture film and used as backgrounds behind animation cels. "The Rotograph" technique went into more general use known as "Aerial Image Photography" and was a main staple in animation and optical effects companies for making titles and various forms of matte composites.

In addition to the theatrical comedy films, Fleischer produced technical and educational films including "That Little Big Fellow"[7] and "Now You're Talking" for A.T.&T.[8] In 1923, he made two 20-minute features explaining Albert Einstein's "Theory of Relativity"[9] and Charles Darwin's "Evolution"[10] using animated special effects and live action.

Red Seal

In 1924,Fleischer partnered with Edwin Miles Fadiman, Hugo Riesenfeld, and Lee DeForest to form Red Seal Pictures Corporation, which owned 36 theaters on the East Coast, extending as far west as Cleveland, Ohio. During this period, Fleischer invented the "Follow the Bouncing Ball" technique in his Ko-Ko Song Car-Tunes series of animated sing-along shorts. Of the 36 Song Car-Tunes 12 used the deForest Phonofilm sound-on-film process. This preceded Walt Disney's Steamboat Willie (1928), which has been erroneously cited for decades as the first cartoon to synchronize sound with animation. The Song Car-Tunes series lasted until early 1927 and were interrupted by the bankruptcy of the Red Seal company—just five months before the official start of the sound era.

Alfred Weiss, owner of Artcraft Pictures approached Fleischer with a contract to produce cartoons for Paramount. Due to legal complications of the bankruptcy, the "Out of the Inkwell" series was renamed The Inkwell Imps and ran from 1927 to 1929. This was the start of Fleischer's relationship with the huge Paramount organization, which lasted for the next 15 years. After a year, the Fleischer brothers started experiencing mismanagement under Weiss, and left the company in late 1928. Inkwell Films, Inc. filed bankruptcy in January 1929, and Fleischer formed Fleischer Studios, Inc. in March 1929.

Fleischer Studios, Inc.

Fleischer first set up operations at Carpenter-Goldman Laboratories in Queens with a small staff. (See Fleischer Studios). After eight months, his new company was solvent enough to move back to its former location at 1600 Broadway, where it remained until 1938. While with Carpenter-Goldman, Fleischer started producing Industrial Films including Finding His Voice (1929), a demonstration film illustrating the Western Electric Variable Density sound recording and reproduction method. In spite of the conflicts with Weiss, Fleischer managed to negotiate a new contract with Paramount to produce a revised version of the "Song Car-tunes" renamed, "Screen Songs" produced with sound beginning with "The Sidewalks of New York"

During this early in the sound era, Fleischer produced many technically advanced films that were the result of his continued research and development that perfected the Post-production method of sound recording. Several of these devices provided visual cues for the musical conductor to follow. As dialogue and songs became major elements, more precise analysis of soundtracks was possible through other inventions from Fleischer such as "The Cue Meter."

The "Queen of the Animated Screen"

Max Fleischer's most famous character, Betty Boop, was born out of a cameo caricature in the early Talkartoon,Dizzy Dishes (1930). Fashioned after popular singer, Helen Kane, she originated as a hybrid poodle/canine figure and was such a sensation in the New York preview that Paramount encouraged Fleischer to develop her into a continuing character. While she originated under Veteran Animator, Myron "Grim" Natwick, she was transformed into a totally human female under Seymour Kneitel and Berny Wolf and became Fleischer's biggest star.

Helen Kane vs Max Fleischer

The "Betty Boop" series began in 1932, and became a huge success for Fleischer. That same year, popular singer, Helen Kane filed a lawsuit against Max Fleischer, Fleischer Studios, and Paramount claiming that the cartoons were a deliberate caricature of her, created unfair competition, and had ruined her career. The suit went to trial in 1934. After exhaustive examination Fleischer was worried that he would lose the suit until an early sound test film of an obscure Black performer, "Baby" Esther Jones was shown as key evidence. The film disproved Miss Kane's claims as originator of the singing style.

Unique Content

Fleischer's cartoons were very different from the Disney product, both in concept and in execution. They were rough, rather than refined. The Fleischer approach was sophisticated, focused on surrealism, dark humor, adult psychological elements, and sexuality. The Fleischer environments were grittier and urbane, often set in squalid surroundings—a reflection of the Depression as well as German Expressionism which Max embraced.

Construction processes and machinery were found in some stories, mirroring Max's view of mechanics as the art form of the 20th Century. But most of all, Fleischer saw animation as "the cartoonist's cartoon" and in his earlier works avoided the literal approach that Disney was taking. As Fleischer stated, "if it can be done in real life, it isn't animation."

Greatest Triumph

Fleischer's greatest business decision came with his licensing of the comic strip character Popeye the Sailor, who was introduced to audiences in the Betty Boop cartoon, Popeye the Sailor (1933). Popeye became a box office champion and was one of the most successful screen adaptations of a comic strip in cinema history. Much of this success was due the perfect match of the Fleischer Studio style combined with its unique use of music. By the late 1930s a survey indicated that Popeye had eclipsed Mickey Mouse in popularity, challenging Disney's presence in the market.

Fleischer and Paramount

During its zenith by the mid 1930s, Fleischer Studios was producing four series, Betty Boop, Popeye, Screen Songs, and Color Classics, resulting in 52 releases each year. From the very beginning, Fleischer's business relationship with Paramount was a joint financial and distribution arrangement, making his studio a service company supplying product for the company's theaters. During the Depression, Paramount went through four bankruptcy reorganizations, which affected their operational expenses.

As founding member of The Society of Motion Picture Engineers, Max was aware of the technical advancements of the industry, particularly in the development of color cinematography. Due to Paramount's financial restructuring, Max was unable to acquire the three-color Technicolor process from the start. This created the opportunity for Walt Disney, who was then a small fledgling producer to acquire a four-year exclusivity. With this, he created a new market for color cartoons beginning with "Flowers and Trees" (1932). In 1934 Paramount approved color production for Fleischer, but he was left with the limited two-color processes of Cinecolor (red and blue) and Two-Color Technicolor (red and green) for the first year of his Color Classics. The first entry, "Poor Cinderella" was made in the two-emulsion/two color Cinecolor Process and starred Betty Boop in her only color appearance. By 1936, Disney's exclusivity had expired, and Fleischer had the benefit of the three-color Technicolor Process beginning with "Somewhere in Dreamland."

These color cartoons were often augmented with Fleischer's patented three-dimensional effects promoted as "The Stereoptical Process," a precursor to Disney's Multiplane. This technique used 3-D model sets replacing flat Pan Backgrounds, with the animation cels photographed in front. This technique was used to the greatest degree in the two-reel Popeye Features Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor (1936) and Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba's Forty Thieves (1937). These double-length cartoons demonstrated Fleischer's interest in animated feature films. While Fleischer petitioned for this for three years, it was not until the success of Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) that Paramount executives realized the value of Max's proposals and ordered one for a 1939 Christmas release. But this request came at an awkward time.

Decline

The popularity of the Popeye cartoons created a demand for more. To meet Paramount's demands the studio was challenged with rapid expansion, production speed ups, and crowded working conditions. Finally in May 1937, Fleischer Studios was affected by a five-month strike, resulting in a boycott that kept the studio's releases off theater screens until November. Max, having a paternal attitude towards his employees took it personally as if he had been betrayed and developed an ulcer.

Then in March 1938, Paramount approved Max's request to produce a feature just when he was preparing to move the studio from New York City to Miami, Florida. The relocation was motivated by several reasons, some related to the strike, others due the need for more space and the lure of a tropical work environment. Once in Miami relations between Max and Dave began deteriorating starting with the pressures to deliver their first feature complicated further by Dave's adulterous affair with his secretary, Mae Schwartz.

Jonathan Swift's classic, "Gulliver's Travels" was a favorite of Max's and pressed into production. Fleischer and Paramount originally budgeted the film at $500,000—the same miscalculation made by Disney with "Snow White. The final cost for "Gulliver's Travels" was three times, or $1.5 million. It played limited engagements in only 30 theaters during the Christmas season 1939 and made $3 Million, giving Paramount a profit of $1.5 Million before going into foreign release. But Fleischer Studios was penalized $350,000 for going over budget, and the contract did not allow Max and Fleischer Studios participation in the foreign earnings.

In 1940, Max was relegated business affairs and continued technical development. His efforts resulted in a reflex camera viewfinder and line transfer methods to replace the time consuming and tedious process of cel inking. That same year Fleischer and Paramount experienced lost revenues due to the failure of the new series "Gabby," "Animated Antics," and "Stone Age" all launched under the leadership of Dave. After Republic Studios allegedly failed to develop "Superman" as a live action serial, Max acquired the license that fall and initiated development.

The cost for the "Superman" series has been grossly overstated for decades, based on Dave Fleischer's 1968 Oral History Interview. The actual figure stated in Fleischer's contract was in the $30,000 range, twice the cost of a Popeye cartoon. "Superman" was a reflection of the type of "serious" cartoons that were not being made by rival studios. And their science fiction fantasy elements appealed to Max's interests, finally leading the studio into maturity and relevance for the 1940s. But it came too late. Today, the Max Fleischer Superman cartoons are considered the final triumph of this great pioneer and his innovative studio.

The End of Fleischer Studios

The early returns on "Gulliver" prompted Paramount President, Barney Balaban to order a second feature for their 1941 Christmas release. This second feature, Mr. Bug Goes to Town was unique, having a contemporary setting and was technically superior to "Gulliver's Travels." Paramount had high hopes for its Christmas 1941 release, which was well received by critics during its December 5 preview. Contrary to the understanding for decades, the bombing of Pearl Harbor did not "cancel" its release especially when Paramount's other releases continued to go forward. The exhibitors rejected it, fearing that it would not do business. And with the abolition of Block booking Paramount could not force its release, and made no creative effort to market it.

With the cancellation of Paramount's Christmas release, Max was called to a meeting with Balaban in New York where he asked him for his resignation, Dave having resigned the month before. Paramount finished out the remaining five months of the 1941 Fleischer contract with the absence of both Max and Dave Fleischer and the change to Famous Studios became official on May 27, 1942. Paramount installed new management, among them Max's son-in-law, Seymour Kneitel.

Later career

Unable to form a studio for the demand for military training films, Fleischer was brought in as head of the Animation Department for the industrial film company, The Jam Handy Organization in Detroit, Michigan. While there he supervised the Technical and Cartoon Animation Departments, producing training films for the Army and Navy. Fleischer was also involved with Top Secret research and development for the war effort including an aircraft bomber sighting system. In 1944, he published "Noah's Shoes," a metaphoric account of the building and loss of his studio, casting himself as Noah.

Following the war, he supervised the production of the animated adaptation of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1948), sponsored by Montgomery Ward. Fleischer left Handy in 1953 and returned as Production Manager for the Bray Studios in New York, where he developed an educational television pilot about unusual birds and animals titled, "Imagine That!"

Max eventually formed a friendship with his old rival Walt Disney, who welcomed Max to a reunion with former Fleischer animators who were by then employed by Disney. However, in his collection of memoirs entitled Just Tell Me When To Cry, Fleischer's son Richard, working for Disney directing his adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, relates how, at the mere mention of Disney's name, Max would mutter, "That son-of-a-bitch."

Fleischer won his lawsuit against Paramount in 1955 over the removal of his name from the credits of his films. While Fleischer had issues over the breach of contract, he had avoided suing for a decade to protect his son-in-law, Seymour Kneitel, who was a lead Director at Paramount's Famous Studios. In 1958, Fleischer revived Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc. and partnered with his former animator, Hal Seeger to produce 100 color Out of the Inkwell (1960–1961) cartoons for television. Actor Larry Storch performed the voices for Koko and supporting characters Kokonut and Mean Moe. While Max appeared in the unaired pilot, he became too ill to appear in the series, and while in poor health spent the rest of his regaining ownership of "Betty Boop."

Fleischer, along with his wife Essie, moved to the Motion Picture Country House in 1967. On September 25, 1972, Max Fleischer passed away from Arterial Sclerosis of the Brain, and the press announced the passing of Max Fleischer, "Dean of animated cartoons." His untimely death preceded the reclaiming of this star character, "Betty Boop" and a national retrospective.

The "Betty Boop Scandals of 1974" started the Fleischer Renaissance with new 35mm prints of a selection of the best Fleischer cartoons made between 1928 and 1934. This was followed by "The Popeye Follies". These special theatrical programs generated interest in Max Fleischer as the alternative to Walt Disney, spawning a new wave of film research devoted to an expanded interest in animation beyond trivial entertainment. Animation is now being recognized as an art as well as a science due to the vision and life work of Max Fleischer.

References

- ↑ Ray Pointer (2016) "The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer: American Animation Pioneer". McFarland and Company ISBN 978-1476663678

- ↑ Maltin, Leonard (1987): Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. Penguin Books

- ↑ Rotoscoping

- ↑ Out of the Inkwell. Die Zeichentrickfilme von Max und Dave Fleischer at the Wayback Machine (archived January 11, 2005) von Mark Langer, in: Blimp Film Magazine, No. 26

- ↑ Fleischer, Richard (2005). 'Out of the Inkwell: Max Fleischer and the Animation Revolution. University Press of Kentucky. p. 2. ISBN 0-8131-2355-0.

- ↑ J.C. Maçek III (2012-08-02). "'American Pop'... Matters: Ron Thompson, the Illustrated Man Unsung". PopMatters.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eroI30Lfv6Q

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CgYH3w4Rzxk&spfreload=10

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nb7GzyUemO0&list=PLYkANRmww0Eqvun7opHl2e1XmmmEqyYA

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BRYJDUazeJg&spfreload=10

External links

-

Media related to Max Fleischer at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Max Fleischer at Wikimedia Commons - Max Fleischer at the Internet Movie Database

- Freely downloadable Max Fleischer cartoons

- The history of the Fleischer's Popeye series

- Max Fleischer at Find a Grave

- Max Fleischer Biography