Mary's Well

Mary’s Well (Arabic: عين العذراء, ʿAin il- ʿadhrāʾ or "The spring of the Virgin Mary") is reputed to be located at the site where the Angel Gabriel appeared to Mary and announced that she would bear the Son of God - an event known as the Annunciation.

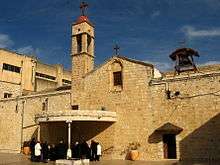

Found just below the Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation in modern-day Nazareth, the well was positioned over an underground spring that served for centuries as a local watering hole for the Arab villagers. Renovated twice, once in 1967 and once in 2000, the current structure is a symbolic representation of the structure that was once in use.

In religious texts

The earliest written account that lends credence to a well or spring being the site of the Annunciation comes from the Protoevangelium of James, a non-canonical gospel dating to the 2nd century. The author writes:

"And she took the pitcher and went forth to draw water, and behold, a voice said: 'Hail Mary, full of grace, you are blessed among women.'"[1]

However, the Gospel of Luke does not mention the drawing of water in its account of the Annunciation. Similarly, the Koran records a spirit in the form of a man visiting a chaste Mary to inform her that the Lord has granted her a son to bear, without referencing the drawing of water, but records a stream of water coming up from the ground at her feet when she was giving birth of Jesus in the same passage of the Koran: Sura 19:16-25.

Through history

| History of the Levant |

|---|

| Stone Age |

| Ancient history |

| Classical antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

| Modern history |

An underground spring in Nazareth traditionally served as the city’s main water source for several centuries, possibly millennia; however, it was not always referred to as "Mary's well" or "Mary's spring". In his book, The Bible as History, Werner Keller writes that "Mary's Well" or "Ain Maryam", as the locals called it, had been so named since "time immemorial" and that it provided the only water supply in the area.[2] William Rae Wilson also describes "a well of the Virgin, which supplied the inhabitants of Nazareth with water" in his book, Travels in Egypt and the Holy Land (1824).[3]

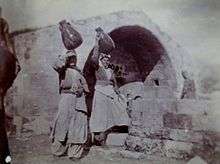

James Finn, then British Consul in Jerusalem, visited Nazareth in late June 1853 and his company pitched their tents near the fountain, - the only fountain there. He writes that "the water at this spring was very deficient this summer season, yielding only a petty trickling to the anxious inhabitants. All night long the women were there with their jars, chattering, laughing, or scolding in competition for their turns. [ ] It suggested a strange current of ideas to overhear pert damsels using the name of Miriam (Mary), in jest and laughter at the fountain of Nazareth"[5]

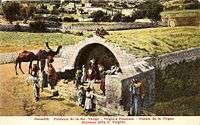

While the current structure referred to as Mary's Well is a non-functional reconstruction inaugurated as part of the Nazareth 2000 celebrations,[6] the traditional Mary's Well was a local watering hole, with an overground stone structure. Through the centuries, villagers would gather here to fill water pitchers (up until 1966) or otherwise congregate to relax and exchange news.[7] At another area not too far off, which tapped into the same water source, shepherds and others with domesticated animals would bring their herds to drink.

The Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation, located a little further up the hill from the current site of Mary's Well, is a Byzantine era church built over the spring in the 3rd century, based on the belief that the Annunciation took place at the site. The Catholic Church believes the Annuciation to have taken place less than 0.5 km away at the Basilica of the Annunciation, a now modern structure which houses an older church inside of it that dates from the 4th century.

Recent Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations by Yardenna Alexandre and Butrus Hanna of the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1997-98 - sponsored by the Nazareth Municipality and the Government Tourist Corporation - discovered a series of underground water systems and suggested that the site today known as Mary’s Well served as Nazareth's main water supply from as early as Byzantine times. Despite having found Roman era potsherds, Alexandre's report claimed hard evidence of Roman-era use of the site was lacking.[8][9]

Bathhouse

In the late 1990s, a local Nazareth couple, Elias and Martina Shama, were trying to discover the source of a water leak in their gift shop, Cactus, just in front of Mary’s Well.[10] Digging through the wall, they discovered underground passages that, upon further digging revealed a vast underground complex. A North American research team conducted high-resolution ground penetrating radar (GPR) surveys at a number of locations in and around Mary’s Well in 2004-5 to determine appropriate locations for further digging to be conducted beneath the bathhouse. Samples were collected for radio-carbon dating and the initial data from GPR readings seem to confirm the presence of additional subterranean structures.[11]

In 2003, archaeologist Richard Freund stated his belief that the site was clearly of Byzantine origins: ""I am sure that what we have here is a bathhouse," he says, "and the consequences of that for archaeology, and for our knowledge of the well, are enormous."[12]

Carbon 14 dating was done on 3 samples of charcoal, each was found to come from a very different time period, indicating the bath house had been used in multiple periods, and at least was used sometime between 1300–1400 CE.[13]

References

- ↑ Chad Fife Emmett (1995). Beyond the Basilica:Christians and Muslims in Nazareth. University of Chicago Press. p. 81. ISBN 0-226-20711-0.

- ↑ Dolores Cannon (2000). Jesus and the Essenes. Ozark Mountain Publishing. p. 110. ISBN 1-886940-08-8.

- ↑ William Rae Wilson (1824). Travels in Egypt and the Holy Land. Oxford University. p. 212.

- ↑ “Fountain of the Virgin, Nazareth.” A Month in Palestine and Syria, April 1891. New Boston Fine and Rare Books, 1 February 2012. Web. 4 February 2012. <http://www.newbostonfineandrarebooks.com/?page=shop/disp&pid=page_PalestineSyria&CLSN_1291=13281208221291adfc56628c3b7bbb6e>

- ↑ James Finn: Stirring Times, or, Records from Jerusalem Consular Chronicles of 1853 to 1856. Edited and Compiled by His Widow E. A. Finn. Volume 2, p. 23, London 1878.

- ↑ Daniel Monterescu and Dan Rabinowitz (2007). Mixed Towns, Trapped Communities: Historical Narratives, Spatial Dynamics. p. 195. ISBN 0-7546-4732-3.

- ↑ William Eleroy Curtis (1903). To-day in Syria and Palestine. F.H. Revell company. p. 244.

- ↑ Alexandre, Yardenna. 2012. Mary's Well, Nazareth. The Late Hellenistic to the Ottoman Periods. Jerusalem, IAA Reports 49.

- ↑ Yardenna Alexandre. "Excavations at Mary's Well, Nazareth". Israeli Antiquities Authority. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ↑ SHACHAM, Tzvi. 2012. Bathhouse from the Crusader Period in Nazareth in Kreiner, R & W. Letzner (eds.). SPA. SANITAS PER AQUAM. Tagungsband des Internationalen Frontinus-Symposums zur Technik und Kulturgeschichte der antike Thermen. Aachen, 18-22. Marz 2009 : 319-326. BABESCH SUPPL. 21

- ↑ Harry M. Jol; et al. "Nazareth Excavations: A GPR Perspective" (PDF). Drew University, NJ. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ↑ Jonathan Cook (22 October 2003). "Is This Where Jesus Bathed?". The Guardian.

- ↑ Boaretto, Elisabetta. "Nazareth Bath Radiocarbon Samples from 2003 Excavation" (PDF). Israel Antiquities Authority. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Nazareth. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Well of St. Mary. |

Coordinates: 32°42′24.16″N 35°18′5.62″E / 32.7067111°N 35.3015611°E