Maritime Union

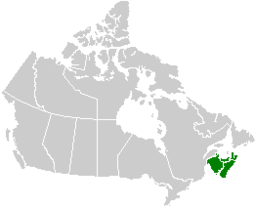

Maritime Union is a proposed political union of the three Maritime provinces of Canada – New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island – to form a single new province.[1] This vision has sometimes been expanded to a proposed Atlantic Union, which would also include the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The idea has been proposed at various times throughout Canadian history. Most recently, it was reintroduced in November 2012 by Stephen Greene, John D. Wallace and Mike Duffy, three Conservative Senators from the region.[1] As of 2012, a union of the three Maritime provinces would have a population of approximately 1.8 million, becoming the fifth largest Canadian province by population.[1]

The Maritime provinces already cooperate to jointly provide some government services, especially in the areas of purchase and procurement.[1]

History

Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick were administered as parts of Nova Scotia, until 1769 and 1784, respectively. The region, at the time of French colonisation, was referred to in its entirety as Acadia. After Acadia fell to the British, following the Seven Years' War (what is today known as the Nova Scotia peninsula had been in British possession post-1713), the entire region was amalgamated into a single colony named Nova Scotia.

During the 1760s, the British split St. John's Island (the present-day Prince Edward Island) into a separate colony, only to merge it again with Nova Scotia several years later. By the 1780s, with the influx of Loyalist refugees from the American Revolutionary War, the disparate geographic regions that comprised Nova Scotia were again split into separate colonies. St. John's Island, New Brunswick and Cape Breton Island all received autonomy with their respective colonial administrations and capitals.

By the 1820s, Cape Breton Island was re-merged into Nova Scotia to free up that island's lucrative coal resource royalties, however the remaining two colonies of Prince Edward Island (renamed as such from St. John's Island in the 1790s) and New Brunswick maintained their colonial autonomy. During the late 1840s, Nova Scotia became the first colony in British North America to have responsible government and by the mid-1850s, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island had undergone similar political reforms.

The reorganisation of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia into a single British colony was considered in 1863 and 1864 by Arthur Hamilton Gordon, the Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick. The concept of a political union was formally discussed at the Charlottetown Conference in 1864 when Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island were individual colonies in British North America, but that meeting resulted in Confederation of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Canada, not just of the Maritime colonies or Newfoundland.

The Saint John Telegraph-Journal in 1925 stated that the idea "could become an intensely practical issue", but "we should concentrate of Maritime co-operation for Maritime advancement."[2]

The idea has been raised from time to time during the 20th century, particularly during the late 1990s in the face of declining regional transfer and equalization payments from the federal government. The discussion was quietly encouraged by politicians in other provinces with the hopes of using such a union to alter the balance of representation in the federal House of Commons and the Senate, based on the belief that the Maritimes are over-represented for their relatively small populations.

In 1990, Nova Scotia Premier John Buchanan stated that if Quebec were to secede from Canada, separating English-speaking Canada into two parts, the Atlantic provinces would be "absurd" to try to form their own country and that there would be "no choice" but to seek to join the United States. Although he retracted his statement after criticism,[3] in 2001 an American author similarly stated that as the Maritime provinces require substantial transfer payments from Ottawa they would not be a viable independent country. He speculated they might combine, with or without Newfoundland, to make themselves more attractive for admission into the United States as a single state.[4]

Regional cooperation

Support for a union of the three provinces has historically ebbed and flowed, in conjunction with various socio-economic and political events throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. In the immediate years following Confederation, the anti-Confederate movement in the region advocated Maritime Union and separation from the new federation, fearing that the wealth of the provinces would be sapped to support development and growth of central and western Canada.

The concept gained credibility in the 1960s at a time when Maritime governments, in partnership with the federal government, were progressively tackling economic underperformance with various regional development programs. The growth of civil service and social program expenditures in the three provinces, coupled with out-migration and declining national political clout, led the provincial governments to examine ways to pool resources and better lobby for the region in Ottawa.

While an actual union was debated in all three provinces, the discussion evolved largely around regional cooperation. Several meetings between all members of the legislative assemblies and the cabinets of the three provinces were conducted during the 1960s, with the result being several important regional cooperation agreements in the areas of health care, post-secondary and secondary education, and in regional intergovernmental coordination, particularly when dealing with Ottawa.

Several institutions were formed by the early 1970s to facilitate intra-regional cooperation, including the Council of Maritime Premiers, and various organisations such as the Maritime Provinces Higher Education Commission and the Land Registry Information Service. During this time, the secondary school curriculum in each province was standardised and provincial funding to post-secondary education was coordinated to eliminate duplication, particularly among professional programs (i.e. education, law, engineering, medicine, pharmacology, dentistry, social work, criminology, veterinary medicine, etc.).

Equally important to the establishment of these formal organisations was the coordination by the mid-1970s among provincial governments for legislation to harmonise policies and programs, as well as to arrive at common positions on federal-provincial negotiations. By the 1980s, the Council of Maritime Premiers was renamed the Council of Atlantic Premiers with the entry of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador into the partnership. The CAP has led all four provincial governments to extend cooperation in the adoption of common consumption taxes, insurance legislation harmonisation, the Atlantic Lottery Corporation, venture capital funding, a harness racing commission, and the coordination of provincial government procurements, among other items.

In addition to historical precedent, there were more pressing reasons to reorganise the colonies. The United States, embroiled in the Civil War, posed a military threat. Many prominent colonial politicians felt that the united colonies would be able to mount a more effective defence. In Britain, the Colonial Office also favoured a reorganisation of British North America. The British hoped that union would make the colonies less reliant on Britain, and therefore less costly to maintain. Gordon's own ambition may also have been a factor—he envisioned himself as the governor of the united Maritime colonies.

The idea of Maritime Union—the reorganisation of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia into a single British colony—was not new. Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick had once been administered as parts of Nova Scotia, until 1769 and 1784, respectively. Several of Lieutenant-Governor Gordon's predecessors, including J. H. T. Manners-Sutton, had also favoured reuniting the three colonies.

Acadia and "New Acadia"

There are several convergent—unique, historically related, and ultimately intertwined—movements for a limited form of sovereignty and independence, stemming from the New Brunswick region of Canada but ultimately encompassing the whole of the Atlantic provinces and even the northeastern corner of the United States.

"Acadians" traditionally refers to a community mainly in New Brunswick that is linguistically French, but is a distinct culture from Quebec. There have been proposals for Acadia to separate from New Brunswick and become a separate province. This was promoted by the Parti Acadien and is similarly represented by the historic "Republic of Madawaska". Currently, there is limited support for this idea, and drawing the borders of a separate Acadian province would be difficult, as Acadians are dispersed throughout the province as well as in smaller numbers in Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Quebec's Magdalen Islands and the U.S. state of Maine.

To help solve this dilemma, Second Vermont Republic essayist Thomas H. Naylor has recently proposed a "New Acadia" which would encompass "Vermont... Maine, New Hampshire, and the four Atlantic provinces of Canada" [5]

The Atlantica Party was created in 2006 to fulfill a similar purpose, of uniting Atlantic Canadians under a common banner and government.[6] However, the party has failed to gain any ground or make any significant impact on the political scene in Atlantic Canada.

A trade zone uniting the region along these lines has also been formally proposed by the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies and the Atlantic Growth Network (organisations based in Halifax, Nova Scotia) with the support of the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, a government agency. Together, they have hosted regular regional conferences promoting the Atlantica trade zone, beginning in 2002 through the last major conference, June 11-June 16, 2007, in Halifax.

However, the proposal has also been criticised by political activists, most notably Maude Barlow of the Council of Canadians, as little more than a regional prototype for a future North American Union.[7]

Gauging support

Within the Maritimes, support for the concept of a formal political union of the three provinces has historically been extremely difficult to quantify by pollsters and politicians. Many Maritimers express support for reducing government expenditures through greater regional cooperation, as in such existing cases as the Maritime Film Classification Board and the Atlantic Lottery Corporation. However, when it comes to actually consolidating the bureaucracies of the three provinces (or four if one counts Newfoundland and Labrador in a larger Atlantic Union), the support dwindles as residents of individual provinces do not wish to see the public sector benefit one particular province over the other.

There is allegedly some support in urban centres of the region, such as Halifax or Moncton as these regions would stand to gain both politically and economically, however mistrust of a formal political union runs deep in Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton, and many parts of New Brunswick and rural Nova Scotia.

Prince Edward Islanders do not wish to give up the freedom of having jurisdictional sovereignty and provincial powers in local control.

Many Cape Bretoners harbour exceptionally deep-seated resentment toward mainland Nova Scotia which has benefited from a relatively strong economy in the Halifax area for many years, something which Cape Bretoners and rural Nova Scotians claim has occurred at their expense. A union with PEI and NB would dilute remaining influence Cape Breton has on provincial affairs which could have a negative impact on the island.

New Brunswickers express the same fears as Prince Edward Islanders, fearing the loss of jurisdiction, and as Cape Bretoners, fearing the dilution of influence over provincial affairs. Of particular concern is the possible linguistic and cultural dilution that the Acadian community of New Brunswick would face - comprising over 1/3 the New Brunswick population, cultural protections guaranteed to Acadians in officially bilingual New Brunswick could be compromised. Although both Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia have Acadian communities as well, both are much smaller and less proportionally significant.

Additionally, many rural mainland Nova Scotians distrust the growing economic domination of Halifax and wish to maintain their remaining influence in provincial affairs.

Issues

A Maritime Union (or an Atlantic Union) would face significant political challenges in gaining broad acceptance across the region, particularly where the existing provinces trace their history since European discovery for several centuries. Entire regional identities, cultures, and economies have developed around the separate French and later British colonies, which constitute the Maritime provinces (or the Atlantic provinces, if Newfoundland and Labrador were to be included).

The history of these political jurisdictions cannot be discounted lightly as Nova Scotia's legislature is the oldest seat of responsible government in the Commonwealth of Nations and Prince Edward Island has the second oldest legislative seat in Canada (Province House) and was the site of the Charlottetown Conference. New Brunswick's legislature is the only officially bilingual assembly of the Maritimes.

Several issues which would dominate any discussion of a theoretical Maritime Union include:

- Capital city: Charlottetown, Fredericton and Halifax all have existing legislature buildings, political traditions and histories for their respective provinces, while the two largest cities in the Maritimes are Halifax and Saint John. This issue would be most contentious, although the possibility of a rotating capital has been suggested, whereby the legislative buildings in each city could be used on a tri-annual basis. Inter-provincial rivalry would likely prove to be extremely contentious in any decision.

- Provincial name: Again, a contentious issue in a region which cherishes its history. Several informal suggestions over the years (mainly by journalists) have included "Acadia",[8] "New Acadia", "The Maritimes", and "New Ireland".

- Official language: The Acadian linguistic minority in New Brunswick, and less-so in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, would demand official bilingualism which is currently in effect in New Brunswick. The Maliseet and Mi'kmaq Nations would also likely contest any linguistic debate.

- Federal representation: Each of the three Maritime provinces has been guaranteed a minimum number of seats in the Canadian House of Commons and the Senate since it joined the Canadian Confederation (Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1867, Prince Edward Island in 1873), even though their relatively small populations (most notably Prince Edward Island's) have never strictly warranted them. It has been suggested that the existing representation guarantees might not be passed on to a united Maritimes. Additionally, a Maritime Union would presumably be represented at the nation's First Ministers' meetings of the Prime Minister and provincial Premiers by only one voice instead of three or four.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Senators revive Maritime union proposal". Toronto Star, November 30, 2012.

- ↑ How 1993, p. 35

- ↑ Morrison, Campbell (1990-04-22). "NOVA SCOTIA LEADER CHIDED FOR TALK OF JOINING U.S. / BUCHANAN RETRACTS STATEMENT UNDER FIRE". The Buffalo News.

- ↑ Nuechterlein, Donald Edwin (2001). America Recommitted: A Superpower Assesses Its Role in a Turbulent World. University Press of Kentucky. p. 133. ISBN 0813127491.

- ↑ Naylor, Thomas (November 9, 2007). "New Acadia". Second Vermont Republic. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Daily News, Amherst (March 17, 2008). "New Atlantica Party has merit". Amherst Daily News. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ "Breaching Atlantica" Archived April 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., Stuart Neatby, June 15, 2006.

- ↑