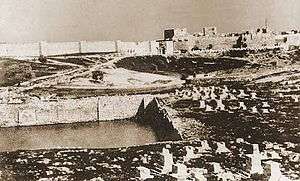

Mamilla Pool

Mamilla Pool is one of several ancient reservoirs that supplied water to the inhabitants of the Old City of Jerusalem.[1] It is located outside the walls of the Old City about 700 yards northwest of Jaffa Gate in the centre of the Mamilla Cemetery.[2][3] With a capacity of 30,000 cubic metres, it is connected by an underground channel to Hezekiah's Pool in the Christian Quarter of the Old City. It was thought as possible that it has received water via the so-called Upper or High-Level Aqueduct from Solomon's Pools,[4] but 2010 excavations have discovered the aqueduct's final segment at a much lower elevation near the Jaffa Gate, making it impossible to function as a feeding source for the Mamilla Pool.[5]

Etymology

There are a number of theories on the origin of the name Mamilla. John Gray writes that it may be a corruption of the Hebrew word for 'the filler' (m'malle'), though that is uncertain.[6] Others indicate it may have been named for its sponsor, Mamilla or Maximilla,[7] or for a church that once stood near the pool that was dedicated to a saint named Mamilla or Babila.[8]

History

The pool's original date of construction is unknown.[4][7]

Roman period

During the rule of Herod the Great, king of the Roman provinces of Judea, Galilee and Samaria in the 1st century BCE, improvements were made to the water supply system in Jerusalem. Two new pools constructed during his reign, the Pool of the Towers and the Serpent's Pool (Birket es-Sultan), were fed by the Mamilla Pool via aqueducts.[9] Itzik Schwiki of the Jerusalem Center Site Preservation Council attributes the construction of the Mamilla Pool itself to Herod.[10]

Byzantine period

Following the Persian capture of Jerusalem from the Byzantines in 614, a large number of Christians were massacred by Jews at the pool.[11][12]

Crusader period

During the period of Crusader rule over Jerusalem in the 12th century, Mamilla pool was known as the Patriarch's Lake, and the Pool of Hezekiah inside the city walls that it fed was known as the Pool of the Patriarch's Bath.[7]

19th century

In the 19th century, Horatio Balch Hackett described the pool:

At the distance of several hundred yards we come to another pool, Birket el-Mamilla, generally supposed to be the Upper Gihon of Scripture, (Isaiah 36, 2.) This reservoir is still used, and on the ninth of April contained three or more feet of water. It is about three hundred feet long, two hundred wide, and twenty feet deep. It has steps at two of the corners, which enable the people not only to descend and fetch up water, but to lead down animals to drink. It is customary, also, to bathe here. [13]

20th century

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the Jerusalem municipality temporarily tried to connect the pool to the Jerusalem water supply, and coated the pool with cement.[11]

Dimensions

The pool's dimensions as recorded by Edward Robinson in the mid-19th century give a depth of 18 feet (5.5 m), a length of 316 feet (96 m), and a width of 200 feet (61 m) at its western end and 218 feet (66 m) at its eastern end. In 2008, the dimensions are given as 291 feet (89 m) x 192 feet (59 m) x 19 feet (5.8 m).[14]

Ecosystem

With the first rains, the pool hosts an ecosystem of crabs, frogs, and insects. During Spring, it becomes a haven for migrating birds.[11] In 1997, a previously unknown species of tree frogs was discovered in the pool. The researchers named their find Hyla heinzsteinitzi, in honor of Heinz Steinitz, a deceased Israeli marine biologist. As of 2007, the species is assumed to be extinct.[15][16]

References

- Jerusalem's water supply: from the 18th century BCE to the present, by Zvi Abells, Asher Arbit, 1993, p. 25

- ↑ Avraham Negev, Shimon Gibson (2005). Archaeological encyclopedia of the Holy Land (Revised, illustrated ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826485717.

- ↑ Robert Walter Stewart (1857). The tent and the khan: A journey to Sinai and Palestine. Oliphant, Hamilton, Adams.

- ↑ Asem Khalidi (Spring 2009). "The Mamilla Cemetery: A Buried History". Jerusalem Quarterly. 37.

- 1 2 Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (2008). The Holy Land: an Oxford archaeological guide from earliest times to 1700 (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-19-923666-4.

- ↑ Wilke Schram (2013). "Pools of Jerusalem". Roman Aqueducts. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ↑ A history of Jerusalem, John Gray, Praeger, 1969, p. 49

- 1 2 3 Denys Pringle (2007). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: The city of Jerusalem (Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 9780521390385.

- ↑ George Williams and Robert Willis (1849). The Holy city: Historical, topographical, and antiquarian notices of Jerusalem, Volume 1. J. W. Parker. pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Bromiley (1982). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J (Revised ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 1024–1025. ISBN 9780802837820.

- ↑ Schwiki, Itzik (February 8, 2005). "The Total Experience from Dismantling and Rebuilding Teaches that This is a Highly Dubious Way of Preservation" (in Hebrew). 02net. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- 1 2 3 Hidden Treasures in Jerusalem, the Jerusalem Tourism Authority

- ↑ Jerusalem blessed, Jerusalem cursed: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Holy City from David's time to our own. By Thomas A. Idinopulos, I.R. Dee, 1991, p. 152

- ↑ Illustrations of Scripture: suggested by a tour through the Holy Land By Horatio Balch Hackett, Heath & Graves, 1856, p. 269

- ↑ The Land of Israel; A Text-Book on the Physical and Historical Geography of the Holy Land Embodying the Results of Recent Research, Robert Laird Stewart, 2008. Page 214

- ↑ Who's to blame for disappearance of a new species of amphibian?, By Ofri Ilani, Haaretz, 2007

- ↑ Grach, Plesser, and Werner, 2007, A new, sibling, tree frog from Jerusalem (Amphibia: Anura: Hylidae), 41: 714.

Coordinates: 31°46′40″N 35°13′14″E / 31.77778°N 35.22056°E