Malayan Union

| Malayan Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ملايان اونياون | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| British colony | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kuala Lumpur | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Malay English | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Political structure | Colony | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | Edward Gent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Decolonisation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | 1 April 1946 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 31 January 1948 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1948 | 132,364 km² (51,106 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Malayan dollar | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||||||||||

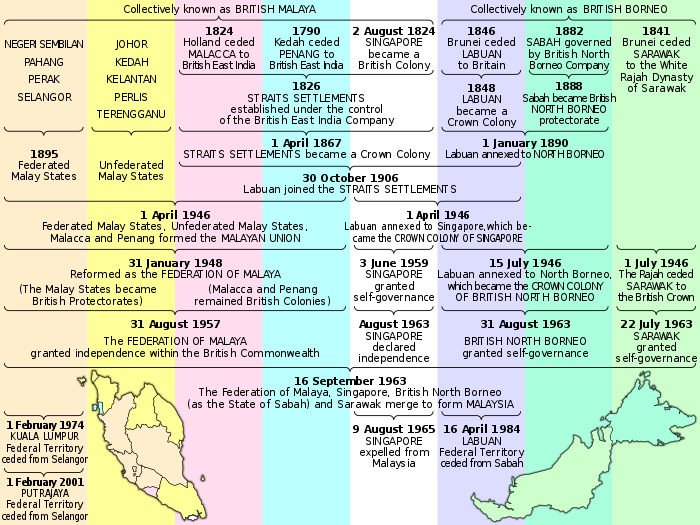

The Malayan Union was a union of the Malay states and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca. It was the successor to British Malaya and was conceived to unify the Malay Peninsula under a single government to simplify administration. Following opposition by the ethnic Malays, the union was reorganized as the Federation of Malaya in 1948.

Formation of the Malayan Union

Prior to World War II, British Malaya consisted of three groups of polities: the protectorate of the Federated Malay States, five protected Unfederated Malay States and the crown colony of the Strait Settlements.

On 1 April 1946, the Malayan Union officially came into existence with Sir Edward Gent as its governor, combining the Federated Malay States, Unfederated Malay States and the Strait Settlements of Penang and Malacca under one administration. The capital of the Union was Kuala Lumpur. The former Strait Settlement of Singapore was administered as a separate crown colony.

The idea of the Union was first expressed by the British on October 1945 (plans had been presented to the War Cabinet as early as May 1944)[1] in the aftermath of the Second World War by the British Military Administration. Sir Harold MacMichael was assigned the task of gathering the Malay state rulers' approval for the Malayan Union in the same month. In a short period of time, he managed to obtain all the Malay rulers’ approval. The reasons for their agreement, despite the loss of political power that it entailed for the Malay rulers, has been much debated; the consensus appears to be that the main reasons were that as the Malay rulers were of course resident during the Japanese occupation, they were open to the accusation of collaboration, and that they were threatened with dethronement.[2] Hence the approval was given, though it was with utmost reluctance.

When it was unveiled, the Malayan Union gave equal rights to people who wished to apply for citizenship. It was automatically granted to people who were born in any state in British Malaya or Singapore and were living there before 15 February 1942, born outside British Malaya or the Straits Settlements only if their fathers were citizens of the Malayan Union and those who reached 18 years old and who had lived in British Malaya or Singapore "10 out of 15 years before 15 February 1942". The group of people eligible for application of citizenship had to live in Singapore or British Malaya "for 5 out of 8 years preceding the application", had to be of good character, understand and speak the English or Malay language and "had to take an oath of allegiance to the Malayan Union". However, the citizenship proposal was never actually implemented. Due to opposition to the citizenship proposal, it was postponed then modified, which made it harder for many Chinese and Indian residents to obtain Malayan citizenship.[3]

The Sultans, the traditional rulers of the Malay states, conceded all their powers to the British Crown except in religious matters. The Malayan Union was placed under the jurisdiction of a British Governor, signalling the formal inauguration of British colonial rule in the Malay peninsula. Moreover, even though State Councils were still kept functioning in the former Federated Malay States, it lost the limited autonomy that they enjoyed as they administered some local and less important aspects of government and the Federal government in Kuala Lumpur controlling vital aspects. State Councils became an extended hand of the Federal government that had to do its bidding. Also, British Residents replacing the Sultans as the head of the State Councils meant that the political status of the Sultans were greatly reduced.[4]

A Supreme Court was established in 1946 of which Harold Curwen Willan was the only Chief Justice.[5]

Opposition, dissolution of the Malayan Union and the creation of the Federation of Malaya

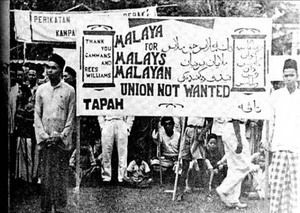

The Malays generally opposed the creation of the Union. The opposition was due to the methods Sir Harold MacMichael used to acquire the Sultans' approval, the reduction of the Sultans' powers, and easy granting of citizenship to immigrants. The United Malays National Organisation or UMNO, a Malay political association formed by Dato' Onn bin Ja'afar on 1 March 1946, led the opposition against the Malayan Union. Malays also wore white bands around their heads, signifying their mourning for the loss of the Sultans' political rights.

Some ex-Malayan government officials, including Sir Frank Swettenham, criticised the way these constitutional reforms were brought about in Malaya, even saying that it went against the principles of the Atlantic Charter. They also encouraged Malay opposition to the Malayan Union.

After the inauguration of the Malayan Union, the Malays, under UMNO continued opposing the Malayan Union. They utilised civil disobedience as a means of protest by refusing to attend the installation ceremonies of the British governors. They had also refused to participate in the meetings of the Advisory Councils, hence Malay participation in the government bureaucracy and the political process had totally stopped. The British had recognised this problem and took measures to consider the opinions of the major races in Malaya before making amendments to the constitution. The Malayan Union was dissolved and replaced by the Federation of Malaya on 1 February 1948.

Evolution towards Malaysia

See also

Notes

- ↑ CAB 66/50 'Policy in Regard to Malaya and Borneo'

- ↑ Ariffin Omar, Bangsa Melayu: Malay Concepts of Democracy and Community, 1945–1950 (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 46. Cited in Ken'ichi Goto, Tensions of Empire: Japan and Southeast Asia in the Colonial and Postcolonial World (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003), p. 222

- ↑ Carnell, Malayan Citizenship Legislation, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 1952

- ↑

- ↑ Ming Ho, Tak. Generations: The Story of Batu Gajah. p. 165.

References

- Zakaria Haji Ahmad. Government and Politics (1940–2006). p.p 30-21. ISBN 981-3018-55-0.

- Marissa Champion. Odyssey: Perspectives on Southeast Asia – Malaysia and Singapore 1870–1971. ISBN 9971-0-7213-0

- Sejarah Malaysia

Coordinates: 3°08′N 101°42′E / 3.133°N 101.700°E

.svg.png)

.svg.png)